photographs and interview by Nan Goldin

photo assistance by Pat Martin

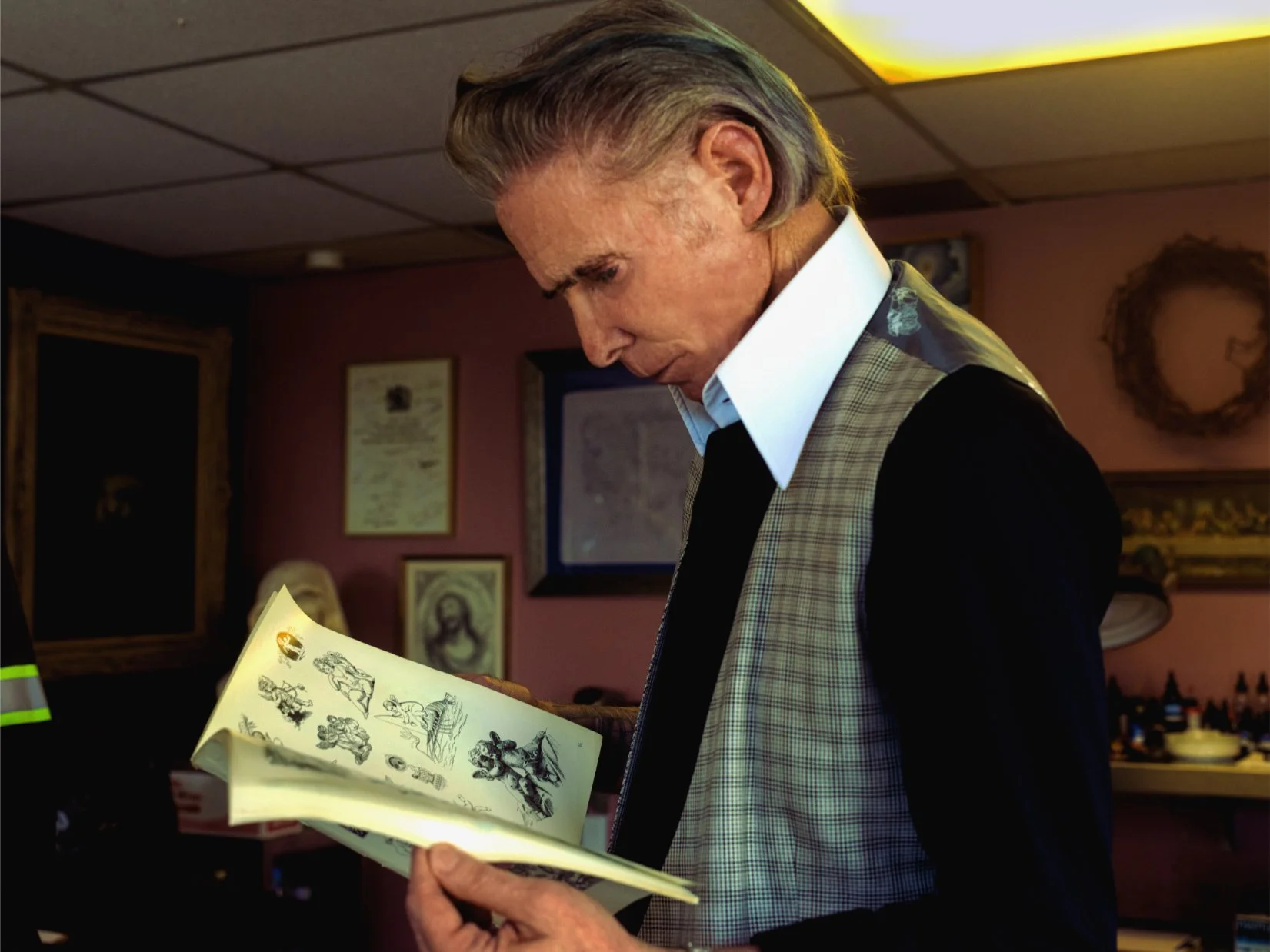

With the aura of a gritty, but warm benediction, legendary tattoo artist Mark Mahoney sounds and looks like a gangster angel that landed on the Sunset Strip. Priestly with high cheekbones, electric blue eyes, tailored suits, handmade Italian shoes, and a perfect pompadour, Mahoney’s shangri-la is Shamrock Social Club; one of the last true Irish tattoo parlors. Mahoney got his start tattooing the Hell’s Angels in Boston. Today, he is one of the world's most famous living tattoo artists. He was responsible for popularizing fine line tattooing, the black and grey style that originated within the Mexican gangs of East Los Angeles. Photographer and artist Nan Goldin met Mahoney in art school when they were just kids. Some of her earliest photographs are of the young tattoo artist: young, free, piercing skin with ink and riding around in cars. They have been friends for over forty years. Mahoney inked Goldin’s first tattoo. On a grey day in Los Angeles after the Oscars, where Goldin’s documentary All The Beauty & Bloodshed (2022) was nominated, she caught up with Mahoney for an intimate interview and a new document of portraits.

NAN GOLDIN: Did you learn anything in art school?

MARK MAHONEY: Zero. I just remember these two lesbian drawing teachers—they described themselves on the first day, one of them was like, “I like earth tones and natural fabrics." And I'm sitting there in shark skin and pointy-toed shoes and I'm like, fuck, we're off to bad start. And then, they asked us to draw flowers. So, I went home and drew, you know, flowers. And I come back and she's like, “No, I want you to draw how flowers smell, not how they look like.”

GOLDIN: So you came to only a few classes?

MAHONEY: I came to only a few classes and then all the cool kids were going to New York. I went with you guys.

GOLDIN: You went earlier than me, with David [Armstrong] and Bruce I think. I came a year later. And Cookie [Mueller] and Sharon [Neisp] came around the same time.

MAHONEY: Yeah, yeah. Was it before you went?

It wasn't much before.

GOLDIN: Were you tattooing in New York? You didn't have a parlor, though, right? It was still illegal to tattoo.

MAHONEY: Yeah. I worked at people's houses. I worked in the Chelsea Hotel quite a few times. I'm going to tattoo you again at the new Chelsea when I do my residency, which I'm excited about. You are going to be the first person I tattoo.

GOLDIN: I love that idea.

MAHONEY: Returning to the scene of the crime.

GOLDIN: And so, when did you move to LA?

MAHONEY: 1980.

GOLDIN: What was the name of the guy who was doing fine line tattoos? Who moved to Hawaii.

MAHONEY: [Don] Ed Hardy

GOLDIN: What happened to him?

MAHONEY: You know, they made that ugly clothing line with his name, they licensed it. It was supposed to just be t-shirts, but they started making everything else. So, he had to sue the guy who licensed his name and he ended up getting a ton of money.

GOLDIN: Good. Did you work with him when you first came up?

MAHONEY: Yeah, I did. He changed the game.

GOLDIN: He was the first fine line tattooer.

MAHONEY: He encouraged it. He was more into color, but when they sold the shop where black and grey [tattooing] started, he bought it so that Freddy [Negrete], Jack [Rudy], and I would have a place to work.

GOLDIN: So good! Freddy's been with you all this time?

MAHONEY: On and off, you know. Freddy, how about that? A famous Mexican gangster tattooer. And then, when he wanted to get clean, he asked me to help him. And the only in I had was at this Jewish rehab, Beit T'Shuvah. A guy I tattoo was the intake manager. I'm like, “You gotta do me a favor, you gotta get Freddy in.” And he goes, “Mark, this is a Jewish rehab.” I'm like, “Don't worry, Freddy’s Jewish as a motherfucker. Let him in. Let him in.” (laughs) And you know, he finally broke down. And he did let him in. But, it turns out Freddy's mom was Jewish from when East LA was transitioning from a Jewish neighborhood to a Mexican neighborhood. So, his dad was a pachucos zoot suiter and his mom was a nice Jewish girl from East LA. He got totally into it. And he got Bar Mitzvahed.

GOLDIN: Now that's a beautiful story. But you know, it's against the Jewish religion to be tattooed. You can't go out of the world with anything that you didn't come in with or something.

MAHONEY: I think the jury is still out on that.

GOLDIN: I came to film the people at Beit T'Shuvah like four or five years ago.

MAHONEY: You did? That’s crazy. (laughs)

GOLDIN: Yeah. We were filming with a cameraman who was pure German. He had never probably met a Jew and he was going to the Passover Seder play—they did one of those. He had no idea what he was looking at. It defined corny.

MAHONEY: I think the rabbi is an ex-convict too.

GOLDIN: Yeah he was wild. Is the place still there?

MAHONEY: Yep. It actually helped a lot of people, man.

GOLDIN: A year and a half before Laura Poitras was on board as the director, when I first started this movie, we shot our own movie. But we couldn't get any money. Then Laura came on and we shot All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. But at the beginning of the movie, we were looking for radical approaches to sobriety.

KUPPER: How did you guys meet originally?

GOLDIN: We were at art school together. It was me and David and Mark and Kimberly and Bruce.

MAHONEY: We would drink beer and drive around in cars.

GOLDIN: That's what we did. We sat on suburban lawns, drank beer, and drove around in cars. Sometimes with the teachers. That was art school. And I lived with Mark’s sister for a while in Cambridge.

MAHONEY: It was great fun. You know, something I remember about living in New York, man, we'd go to three great gigs a night and then we'd go to the Mudd Club afterwards, but you could never say you were having a good time. You had to say, “Oh, I'm so depressed. It sucks.” (laughs) And in retrospect, we were having a ball. Right?

GOLDIN: No, we didn't have to say we were depressed. We just had to act like it.

MAHONEY: But I don't ever remember someone saying, “This is so much fun, ain’t this cool.” (laughs)

GOLDIN: It's true. I never thought of that (laughs). We missed our happy days.

MAHONEY: Yeah, right.

GOLDIN: Well, we’re picking up where we left off.

MAHONEY: That's a good line. We missed our happy days. I think it's absolutely true.

GOLDIN: We're having our happy days now.

MAHONEY: Right? I think that's why we're happy. Yeah. Happy enough. We’re cherishing in a way we didn't really then.

GOLDIN: So, did you come out to LA with Bruce?

MAHONEY: No, I came out with this girl from high school. We drove out and I went to the tattoo shop the first day and I asked them for a job and then they said, “Well bring someone down tomorrow and tattoo them. And if it works out good, we'll give you a job.” So, my friend who lived out here was in the Merchant Marines, he didn't have any tattoos. I told him, “You're getting a fucking tattoo.” So, I brought 'em down and I did a little tattoo on him and I got the job.

GOLDIN: Wow. The second day you were here. And were you living with Bruce?

MAHONEY: We lived together in San Pedro for a while, yeah. We had a cool house. It was crazy.

GOLDIN: Was David here too?

MAHONEY: Yeah, yeah. They came out together with the monkey, Joseph, who died en route. They went to a Pizza Hut in Mississippi and left him in the car with the windows rolled up.

GOLDIN: Oh, Jesus. Do you remember going to my parents' house?

MAHONEY: And the monkey got loose?

GOLDIN: Joseph escaped to the backyard and we had to call the zoo to come … no, the fire department. He wasn't coming back. And my parents were out of town and we were having too much fun in our house.

MAHONEY: Wild. I didn't think we would ever get ‘em out of that tree.

GOLDIN: I found a good picture. It's Bruce with the monkey.

KUPPER: Nan, can you talk about your first tattoo experience with Mark?

GOLDIN: Yeah, that was at Bruce's house on Elizabeth Street. There's pictures of it. I'm high as a kite. Happy as hell. Laying down on the bed with a beer in my hand. The first tattoo was a bleeding heart on my ankle.

MAHONEY: Yeah, like a sacred heart.

GOLDIN: I collected sacred hearts.

MAHONEY: And the ankle sucks. It hurts.

GOLDIN: Yeah, it's not doing so well.

MAHONEY: We could redo it someday. Clean it up. You've earned that shit.

KUPPER: So Mark, how long were you in New York between Boston and Los Angeles?

MAHONEY: A few years. I went back and forth to Boston and worked on the Hell's Angels.

KUPPER: Tell me about that experience. Working with biker gangs.

MAHONEY: You know what, I look back on that now, those guys were so nice to me. I was so lucky. I think they were happy they didn't have to drive to Rhode Island and they liked that I could draw whatever they wanted on 'em, and I'd go to the clubhouse and have a ball. Yeah. That was wild. That was cool.

KUPPER: Did that experience inspire you to open your own social club?

MAHONEY: You know, when you’d go to tattoo shops in the old days, you'd go to Rhode Island and the guys were just mean, man. I remember asking a guy like this if there was a school for tattooing. And he said [imitating a growling voice], “Yeah, reform school.” There was this veil of secrecy around the tattoo world. It’s impenetrable. But I told myself that if I ever have a shop, you know, I want people to be nice to people. And that's why I call it the social club. It’s okay to socialize.

KUPPER: I feel like you've developed your own sort of countercultural shangri-la. Can you talk a little bit about that, and what your personal definition of utopia is?

MAHONEY: Well, I have been wanting to get Nan to move out here for a very long time because I know that the sunshine and California has been good for my mental health. You know what I mean? My mother had depression in that fuckin’ grey Boston weather. She said the Irish are given to the melancholy and I think that's true. But being in the sunshine, being in LA, it’s utopia to me. And I think Nan would thrive out here. I think she would be directing two movies a year and saying no to ten other ones.

GOLDIN: Jews are given to depression, too. There are two different kinds of guilt. Catholic guilt and Jewish guilt. I like Catholic guilt better than Jewish guilt. It’s more concrete and the imagery is beautiful. The Jewish guilt is endless.

MAHONEY: When you’re Catholic, you can go to confession and all your sins are forgiven.

GOLDIN: And if you’re Jewish you go to a Jewish psychiatrist and never get forgiven.

KUPPER: Nan, what's your personal definition of utopia?

GOLDIN: Utopia evades me. I'm a very dark person. My last show was called, This Will Not End Well. It's a major career retrospective, you know, being sixty-nine and saying, “this will not end well,” it says a lot. I mean, if I could, I would have my friends back. That would be utopian to me. All my friends and the way I feel now. The way I relate to people now with them alive as opposed to being young and an insecure person and all that. So, the way I feel now with them alive, that would be utopia.

MAHONEY: There’s that cherishing thing again. That’s really good.

GOLDIN: And maybe we'll meet them on the other side.