In front of the statue of George Washington across from the New York Stock Exchange

There is something impossibly magical about a whole world painted in polka dots. It’s the kind of world an obsessive-compulsive god might create on a mushroom trip. Obsessive, molecular, psychedelic – the world of Yayoi Kusama is an alternate universe of love and surreality connected by a million dots and nets – which she calls Infinity Nets – that seem to always catch her when her imagination flies too high. Kusama, who was born into a traditional upper-class Japanese family in 1929, has seemingly been misunderstood since birth. Plagued by crippling hallucinations and neuroses since childhood, she found refuge and solace in art. Falling into the currents of multiple art movements, between the waves of post-impressionism, minimalism and pop art, Kusama’s work has remained enigmatic, difficult to define; almost impossible to classify into one particular genre. Yet her dreams of becoming a famous artist would come true during the pivotal (and arguably most productive) years of her career, between 1958 and the late 1960s, when she became a central fixture of the explosive New York City avant-garde movement. She became close friends and collaborated with other important artists, such as Donald Judd and Eva Hesse, and exhibited alongside Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol (with whom, she implies in the following interview, she has had a somewhat contentious relationship). While she is most known for her dot paintings, which deal with themes of love and infinity, Kusama also experimented with other media such as sculpture, writing, film, installation, and performance during her years in New York. She also held “happenings” in the antiwar sprit of the times, many of them involving mass nudity in public places. Once, she even offered sex to Richard Nixon if he would end the Vietnam War. Perhaps because of a combination of exhaustion and disillusionment, Kusama eventually moved back to Tokyo, where she still lives in a mental institution close to her studio. Today, Kusama is as active and inspired as ever, and will be featured in two forthcoming major retrospectives – one at the Tate Modern in London and one in the summer of 2012 at New York’s Whitney Museum. Kusama is also collaborating with Marc Jacobs on a collection for Louis Vuitton. Famously elusive, Kusama was gracious enough to answer a few of our questions and share her important message with us all.

Autre: Can you remember the first time that you knew you wanted to be an artist?

Yayoi Kusama: I recall that when I was a little girl, about 10 years old, my mother, who was vehemently opposed to my becoming an artist, tore up a large painting I had just finished exerting my utmost strength and spending almost a month on.

Autre: You are most known for your intricate painting of dots – what is the psychological or spiritual significance of dots?

Kusama: Since childhood, I have been painting, for no special reason, numerous dots and nets, drawing from the hallucinations that seem to appear endlessly. I can’t explain why if you ask me.

Autre: What is the biggest misconception about your art?

Kusama: When I was in New York, I staged a large number of happenings and anti-art musicals. The shocking scenes that often appeared in those events caused quite a few people, including artists, to criticize and question my thoughts and beliefs as an artist.

Autre: I watched your documentary and there was a scene with you flipping through press about yourself and it seemed like you had some disdain for art critics - is there animosity toward the people who write about you and your art?

Kusama: There were times in the past that I got angry at some members of the press whose writings greatly disrupted my serious pursuit of art and my behavior as an artist

Autre: What was it like in New York during the 1960s with Andy Warhol?

Kusama: Andy and I appeared together before the media on several occasions to discuss art. I found his thoughts and behavior totally different from mine.

Autre: What was your first impression of Andy Warhol?

Kusama: I have never thought about it. I have treaded my own path developing innovative ideas for my artwork. Andy copied my ideas such as repetition and accumulation for his work.

Autre: What are some of your biggest inspirations?

Kusama: My ideas and creativity are the sources of inspiration for me.

Autre: What is one thing you'd like the world to know about you?

Kusama: I would like to dedicate to the whole world a great message. It is a message from Kusama who has struggled to survive as a human being and as an artist, and whose life has been brightly lit and strengthened by her pursuit of truth.

Autre: What does the future hold for Yayoi Kusama?

Kusama: It is my wish to leave a message to the whole world from the universe, a message of love and peace to the people of the world.

Text and interview by Oliver Maxwell Kupper for AUTRE ISSUE 002.

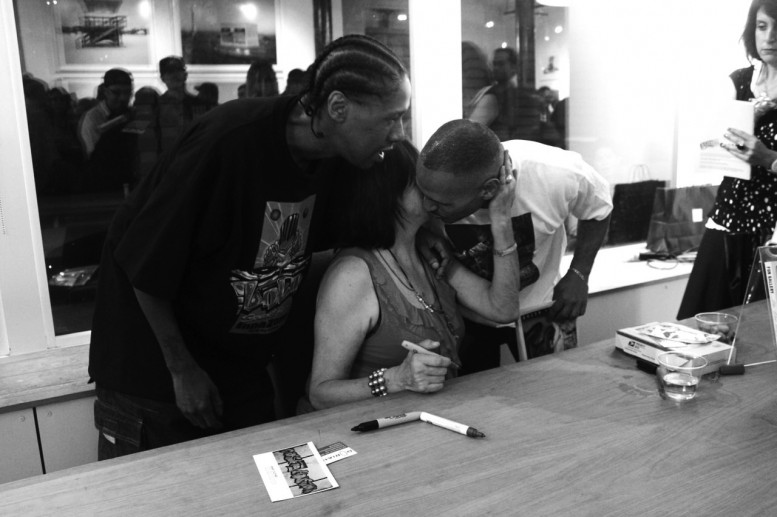

The Anatomic Explosion, Happening in Central Park