“New York is the only place where a girl can graduate from the Scarlett O’Hara School of Business and build an art empire held together with Aqua-Net,” Patti Astor told New York Magazine in 1983, at the height of her reign as “Queen of the Downtown Scene” and co-founder of the legendary FUN Gallery. Astor, who René Ricard famously called “the first natural blonde in town since Edie Sedwick,” has succeeded in doing just that. The Manhattan it-girl, underground film star, and groundbreaking curator tells all in her memoir, FUN Gallery… The True Story.

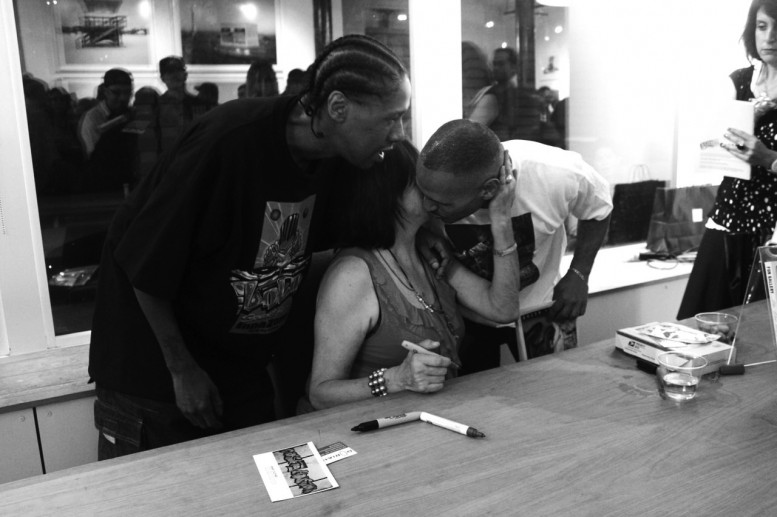

“We did it, motherfuckers!” the diminutive Astor, clad in shocking pink, cried gleefully at her October 6th book launch party at Clic Gallery in Soho, pulling guests Lee Quinones and Charles Ahearn into a tight embrace. FUN Gallery began in 1981, when Bill Stelling approached Astor at an art opening and barbecue being held at her “hideous 65-dollar-a-month apartment” on East 3rd Street (attendees included Keith Haring, Jeffrey Deitch, Futura—who was painting a mural on Astor’s wall, and Kenny Scharf—who busied himself customizing Astor’s kitchen appliances with “cowboy and army figures and glitter”). Stelling had an East Village space that he wanted to transform into a gallery—and social butterfly Astor knew artists (did she ever!). FUN became the first gallery to give important solo shows to Scharf, Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Thanks to the ever-bubbly and vivacious Patti Astor, the gallery brought widespread recognition to graffiti as an art form, showcasing work by emerging street artists such as Fab 5 Freddy, Futura, Zephyr, Dondi, Cey One, Jane Dickson and SHARP. In her memoir, Astor gives us an exclusive look at the glory days of FUN—that short-lived, magnificent, ever-transforming hodgepodge of glamour, sleaze, hip-hop, disco, punk, paint, glitter, knives, garbage cans and two-dollar beers—with the effervescent, unmatched spirit of adventure that made it all possible.

ANNABEL GRAHAM: Can you tell me a bit about how FUN Gallery started?

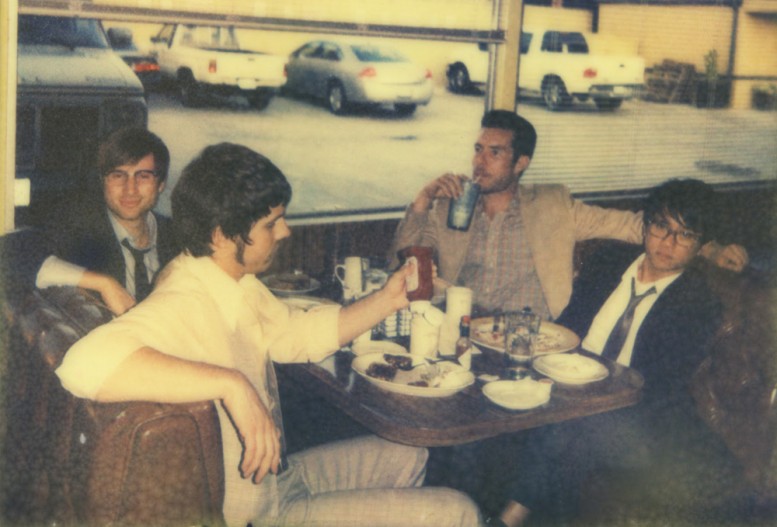

PATTI ASTOR: What I describe in my book is the path that led me to the opening of the FUN Gallery. I moved to the East Village in ’75 and when I first moved over there, all my friends said, “Oh my god, we’re never going to visit you, it’s too dangerous… See you!” And that wasn’t true at all. CBGB’s was the local bar, and Blondie and Talking Heads were the house bands. So we would go there every night… and this period, which covered from maybe ’75 to ’77, ’78… was sort of the punk rock band, the music period… and the film director who I went on to make two feature movies with, with Debbie Harry as a co-star, was Amos Poe. I met him at CBGB’s, and he had done this movie called Blank Generation, which documents CBGB’s. It’s a great movie to look at… if it was sync-sound, it’d be worth like 20 million dollars, but it’s not… but it shows the bands at CBGB’s. So I met all of those guys, and I was very young, about 25 or 26… drinking the two-dollar beers, and that was when I acted in my first feature. And so the next thing that came along after the bands was the underground film scene. Jim Jarmusch is probably the most successful person that came out of that period. Over the next two years, I would make over fourteen beyond-low-budget movies. In Rome ‘78, we’re all running around in togas… We shot Snakewoman entirely on location in Central Park, for five hundred dollars… it’s our homage to the 40’s jungle movies. So everybody was just doing these wild, creative things. What happened though, which is interesting, is that a lot of Underground U.S.A., which was probably my best role, the sort of Sunset Boulevard punk rock version, was shot in the Mudd Club. We couldn’t afford to rent the Mudd Club, so we just shot while it was open, but it’s a fascinating look at the club. Later on, when I did Wild Style, which is the ultimate hip-hop movie, it was the same thing—we were so broke that we just shot in the midst of it. So you get the real scene. All that existed—you’re not going to get some scripted thing. That came later. So I met Fab 5 Freddy…

GRAHAM: How did you meet him?

ASTOR: It’s a good story! It’s actually the pivotal story—this story is what I start the book with, because I just happen to be very lucky. I’m adventurous, so that helps. But I really think that our meeting was so pivotal. I told you about Underground U.S.A., which was playing at St. Mark’s Cinema—which now has turned into a GAP. But at the time it was the hip movie theater, and Underground U.S.A. was running as the midnight movie there for about six months. This is the end of 1980, and no one downtown had heard of rap music, break dancing or graffiti art. It did not exist. We had no idea it was going on. It was all going on in the South Bronx and in Brooklyn. Fab had dragged Futura and a couple of other guys down to see the movie. So the next day, I think it was… I was really hung over, I remember… Duncan Smith, who was a poet-philosopher, was having a big party at his loft for the 100th birthday of Stéphane Mallarmé, the poet. He was serving vodka and cucumber sandwiches. So we’re there, and I see this black guy… which was not that usual on the scene… with the porkpie hat and the shades and everything, and I’m like, “Woah, who’s that?” And of course, everyone was too cool to introduce us. It was a birthday party, so Fred took a little paper plate and he walked up to me and said, “Patti Astor, you’re my favorite movie star. Can I have your autograph?” And I said, “Oh, yeah, of course! You must be my new best friend.” And of course, that’s what he was, and that’s how it really all started. Fred said that I was “down by law.” That’s like the beyond-silver-platinum-American Express card in hip-hop. That means, like, Patti A. is cool. So that meant everybody would talk to me and everything. I got to know all of the guys, and this was when the clubs were all really big, and I was going into Peppermint Lounge. So now the uptown guys are starting to come downtown, they want to go to the clubs and everything. So Futura and Dondi and Zephyr were outside the Peppermint Lounge, in line waiting to get in, and they were like, “Hey Patti!” And I’m like, “Yo guys, what’s up? Come in with me!” Because I always went into the door, and, you know, as soon as they found out that with me they could get into any club in town, I was like double “down by law.” So then what happened was that Futura offered to give me a painting, because that was something that they would do.

By this time, I realized that it was cooler to have a mural, because a mural could not be bought or sold. So I was living in this hideous dump, a sixty-five-dollar-a-month apartment on East 3rd Street, across from the man shelter, which was… we called them “bums” then, but it was like a homeless shelter. It was an awful apartment, but everyone lived on that street. Eric Mitchell, John Lurie… all the stars. I always call it the Street of the Stars. So I said, “Listen, why don’t you just come over and do a mural on my wall in the morning, and in the afternoon we’ll all have an art opening and barbecue! It’s gonna be great!” And so Kenny Scharf also offered to join in, because… and this is what’s so fascinating, I don’t think it happens anymore—that we would just do something. We wouldn’t worry about, “Are we going to make money? How much is this going to cost? Is it going to be organized?” You know, we’d just do it. So Futura and Kenny did their art. Kenny was customizing my appliances… he took my blender and decorated it with paint markers, and glued all these little cowboy and army figures, and glitter and whatever… and then your appliance would be customized. He did that, I made potato salad and ribs, Futura was painting… and then in the afternoon we had the art opening and barbecue. So we’re all there, we’re drinking the two-dollar beers, and Keith Haring is looking out the window and he goes, “Oh shit!” So we all rush to the window, and we see Jeffrey Deitch, who’s one of the biggest figures in art—and was then, too, because he was the art buyer for Citibank—getting out of a cab with Diego Cortez. Even the bums—the bums would all come out when we had parties, they would sit on all the garbage cans outside and listen to the music—they were so impressed that they didn’t even bother to panhandle. So we were all like, “Jeffrey Deitch is coming to this little downtown party… There’s something going on here.” However, that had nothing to do with starting the FUN Gallery. At this point, I needed to get all these guys and all these beer bottles out of my apartment. So my partner Bill Stelling came up to me and said, “I have this little space that I want to fix up and make into a gallery, do you know any artists?” And I said, “Yes, I do.” People always ask me how we got started… we just started. It wasn’t even a graffiti artist at first, it was my ex-husband, Stephen Kramer. We had twenty colored pencil drawings—he was a genius, they were beautiful—he cut them out himself, and we were so broke that we couldn’t frame them, so we shrink-wrapped them like albums. We put them up and sold everything the same day; we made a thousand bucks.

GRAHAM: How do you think the gallery scene has changed nowadays? Had it been a different era, would the FUN Gallery have happened, or was it a product of the times?

ASTOR: You know, I don’t think it’d be possible today. When I did the LACMA show last year, “Art in the Streets,” I had a room that was the FUN Gallery original crew, the people who made the gallery what it was. Those were the men—and one woman—who had one-person shows in the FUN Gallery. I’m looking around now, and over half of those artists are gone. I’m here to make sure that they’re taken care of, that their reputations and their artwork are given the respect they deserve. I’m seeing a younger generation—but I think it’s so difficult now, and I don’t think people really have that spirit of adventure anymore. People are saying, “Patti, bring it back! Bring the FUN Gallery back!” What I really need to bring back is that spirit of adventure—because without that, it’s never going to happen. So find it within yourself. You can make a difference.

You can find Patti Astor's book FUN Gallery… The True Story at Clic Gallery & Bookstore, 255 Centre Street, New York, NY or online. Text and photography by Annabel Graham for Pas Un Autre