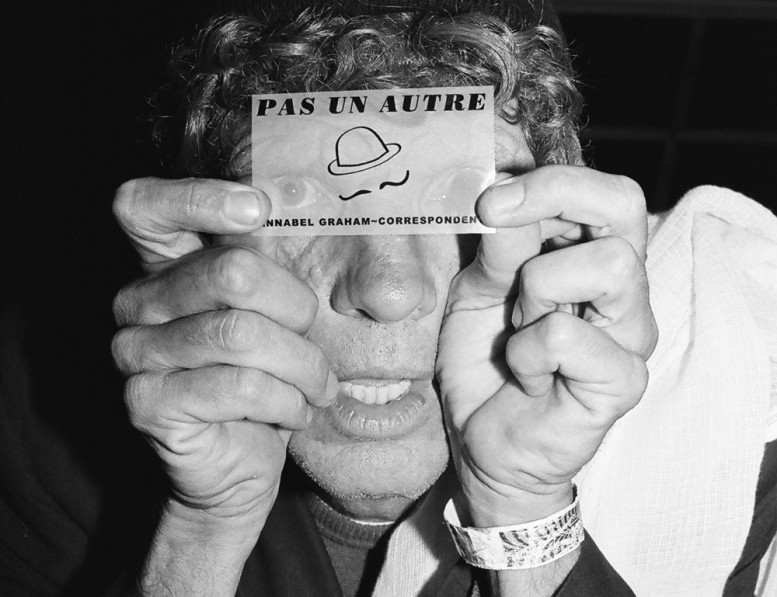

interview by Annabel Graham

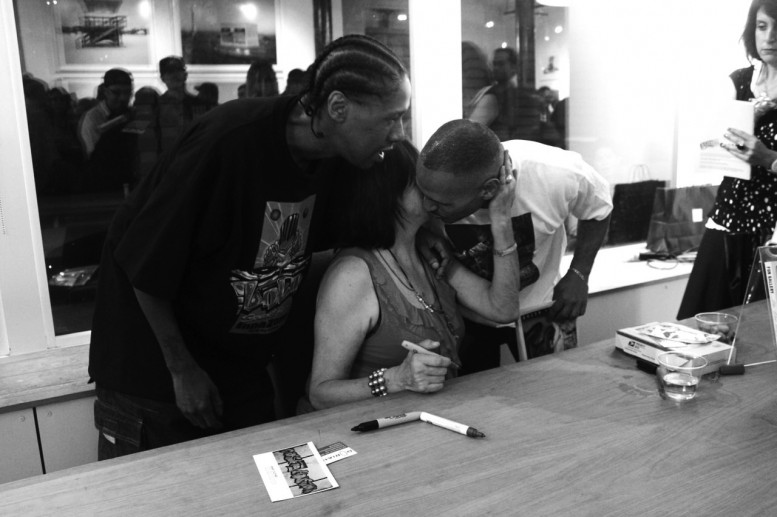

portraits by Paige Strabala

I first met Nada Alic in the fall of 2019, in New York, at a literary reading held at the Nolita headquarters of a women’s sleepwear brand. The small storefront was packed, and readers perched on the edge of a gigantic feather bed in the center of the room. Most of the guests were there to see a certain Instagram poet with an especially rabid fan base—I witnessed actual tears of joy when said poet opened her mouth—but it was Alic who captured my attention. Radiating her trademark blend of confidence, self-deprecation, and deadpan humor, she read from a short story in progress. In it, an anxious, painfully cerebral young woman questions “this whole business of being alive,” pursues an obsessive friendship with a woman named Mona, and considers the pros and cons of lightly grazing her hand across a stranger’s penis. At a cocktail party with her husband’s business associates, Alic’s narrator muses: “They all looked so vulnerable, so up for grabs; concealed only by a thin layer of fabric. I imagined them as windchimes waiting to be struck. The impulse wasn’t sexual, it was destructive. I just stood there, not touching anyone’s penis, quietly frightened by who I was and what I was capable of.” Suffice it to say that I was riveted.

Alic and I struck up a conversation after the reading, exchanged email addresses, and made loose plans to get together for a coffee next time I was in Los Angeles, where she lives. What followed almost immediately was a global pandemic, a government-imposed lockdown, and a 19th-century sort of pen-pal correspondence conducted over the entire year of 2020. Alic’s emails are just as surprising and enjoyable as her short fiction—witty, dark, vulnerable, sharp-edged; weird in all the best ways. The story she read that night in New York (featuring the penis-windchime simile that’s eternally burned into my brain) is now entitled “My New Life”—this past year, it was published in the literary journal No Tokens, where I serve as fiction editor. You can read it here.

2021 was a landmark year for Alic—she married her partner (Ryan Hahn, of the indie band Local Natives), and sold her short story collection, Bad Thoughts, to Knopf, in a two-book deal (her second book, a novel, is slated for release in 2023). The title Bad Thoughts stems from the eponymous Instagram series Alic created in 2020 during quarantine, wherein she posted bimonthly lists of Tweet-like aphorisms that were at once wildly humorous, razor-sharp, and deeply relatable. The stories in the collection—which will be published in July 2022—are brash and heady, breaking established rules of narrative and form. Like the Instagram series, they’re also delightfully funny. In one, the spirit of an unborn child hovers over the bodies of its future parents, willing them to copulate and bring it into embodied existence. In another, a woman’s musician boyfriend goes on tour, leaving her alone in their home for the first time ever; she proceeds to question all of her life choices and tumble down a frighteningly familiar Internet rabbit hole; chaos and body dysmorphia ensue. Alic is well-versed in the awkward, writing into our most neurotic, shameful habits and thought patterns with an unparalleled acuity.

For Autre, I sat down with Alic in her Mount Washington living room to talk about the holiness of humor, becoming an artist with no formal training, and the archetype of the eternal child-god. We’re real-life friends now—a true privilege!—but sometimes I miss our extremely long emails.

ANNABEL GRAHAM: What was your path to becoming a writer?

NADA ALIC: I came up in the 2008ish blogging era; a famously naïve and earnest era of the internet that had yet to be colonized by brands and pathological cynicism. I wrote about music, mostly. I loved music in such a pure and unselfconscious way. I had no ambition to become a writer; I just wanted to support my friends, go to shows, be in that world. Writing was my way in. It wasn’t until my late twenties that I started writing fiction. I would send short stories to my friend Andrea [Nakhla, who is a painter and illustrator], and she would visually interpret them with paintings and drawings, and we made zines together, for fun. Making zines feels incredibly wholesome and old-timey now—I recently had the humbling experience of explaining what a zine was to a 22-year-old. I continued writing short stories from then on, but I never thought of myself as a Writer, and didn’t until about five minutes ago. This was due to my core wound of not having an MFA and never once having lived in New York. I tried compensating for this by reading Twitter, submitting to literary mags, and attending a writing workshop in abandoned strip mall in North Hollywood. Each experience was like passing a test, and I’d emerge with a tiny crumb of belief in myself.

The paradigm shift towards becoming a writer was very slow; it was largely internal, but also required some external factors to align: getting an artist visa, saving up money, quitting my job, getting my own health insurance, finding freelance work to support me through the transition. Just a lot of boring, admin stuff. I felt like I had so much to prove. I still do. But the benefit of feeling like an outsider in the literary world is that it motivated me to work really hard. I felt like there was so much I didn’t know, so I had to seriously commit to the work and forge my own path in the absence of any formal infrastructure or connections or community.

GRAHAM: Did you read a lot as a kid?

ALIC: I enjoyed reading as a kid, but I didn’t grow up in a super intellectual environment. My parents were working class Croatian immigrants; they didn’t have the time for literature and art. That’s not to say they weren’t smart; they were and are far more competent than me in almost every way; they can build a house from scratch, hunt and prepare meat, keep children alive, etc. They could easily survive the apocalypse, whereas I will die within hours of losing my contacts. What they did give me was lots of free time to play, imagine, dance, terrorize my sister, etc. I didn’t start reading for pleasure until my early twenties; mostly just books I’d find in thrift stores. I remember performatively reading guys like Steinbeck, Bukowski and David Foster Wallace because pretentious boys in beanies kept referencing them. It wasn’t until I discovered contemporary fiction writers like Sheila Heti and Tao Lin that I realized what writing could be. Those writers made writing feel accessible and real and exciting to me.

GRAHAM: How are you finding the process of working on a novel? What are you encountering that’s more or less challenging than writing short stories?

ALIC: The story for the novel came to me fully-formed. I felt like I had to pay attention to it, because none of my short stories had come out that way. Writing the story collection was like feeling my way around in the dark. In a lot of ways, I was learning how to write through the process of writing the collection. I didn’t really have a plan or a vision other than “keep going” and “don’t be bad.” My biggest challenge has been sustaining the potency of the short story within a longer form. I don’t want to lose that; I still want every moment to feel funny and alive.

GRAHAM: How do ideas for stories usually come to you? Do you start with a particular element? An image, question, atmosphere, or character?

ALIC: I keep a notes document for random thoughts, ideas, dreams, etc. Often it’ll be about a humiliating or painful encounter that I’ve either observed or experienced, and I’ll want to diffuse it of its power over me. Then I’ll take that idea and stretch it out beyond its limits into absurdity. Like with “The Intruder,” for example, that came from a real experience I had mistaking a friend’s boyfriend for an intruder breaking into my apartment. I was really tired and overworked and somehow forgot I had [house]guests. I woke up in the middle of the night and saw a dark shadowy figure and panicked. I basically jumped out of bed and tried to defend myself before realizing what was happening. It was one of the most embarrassing experiences of my life. In the story, the protagonist doubles down on her paranoia and submits to the fantasy that someone really is out there, watching her, waiting. Submitting to her delusions paradoxically gives her some semblance of control. Most of my characters suffer from some form of delusional thinking, and there’s a lot of humor in that. Humor is a useful device for confronting and overcoming shame, which is my life’s purpose.

GRAHAM: What’s your writing process like? Do you have any routines?

ALIC: I sort of cringe when people talk about their process as if they’re the ultimate authority on it. I remember early on, after I quit my job and committed myself to writing full time, I read a lot about what other people had to say about their creative processes and it really affected me. It just set me up to fail. It was a lot of like, “I wake up at 5am and write till noon, then I eat a cracker and stretch and keep writing till dinner…” I’m very suspicious of that kind of self-mythologizing. Most people who say they write every day are full of shit. Even if they do, who cares? Keep it to yourself! Stop bullying us! Process has very little to do with good art. Reading about how prolific a writer is has never once compelled me to write. I don’t know, maybe it helps other people?

I still don’t really have a routine. I make space for solitude and work every day, but sometimes life gets in the way and I try to forgive myself. The hardest thing for me was unlearning a lot of capitalist programming that had been burned into my brain from years of working in the corporate world. I had to learn to be okay with “wasting time” and letting go of my obsession with productivity. I’m very slow and inconsistent, but I also have this very dogged, Slavic commitment to the work in a bigger, cosmic sense. I feel like larger forces are at work, guiding me. Or haunting me, actually. I can’t really explain it.

GRAHAM: You write about the Internet a lot, and you started an Instagram series entitled Bad Thoughts. What’s your relationship to the Internet like?

ALIC: The internet is so seductive and shiny and infinite, so I have to take mini-breaks or block certain sites for a while in order to spiritually recalibrate. Sometimes I really do confuse it for reality and forget that I’m located in space and time, contained inside a body, etc. That’s when I need to just get up and pee and go for a little human walk outside, feel my blood move.

For Bad Thoughts (the Instagram series), I just had a lot of fear and I wanted to get over myself. When you’re working on something in private for a long time, it can start to feel too precious. I needed to break the spell and stop overthinking it. I just started sharing random thoughts that came to me in a quick and unpolished way. I knew I was going to feel embarrassed, but that was the point. I comforted myself by thinking, whatever, this isn’t my real work. But once I started doing it, it was like this portal opened up in my mind and ideas started pouring in. Not to be a witch or whatever, but I do feel like I was tapping into a spiritual plane through my subconscious mind. It was an interesting experiment. But like with anything, once I started taking it too seriously, or cared too much about what people thought, I knew I had to stop because I didn’t want it to become another “thing” that I did. The ego will identify with anything, even if that thing is meant to set you free. It’s like what Ram Dass says: “all methods are traps.” I might do it again when I’m a little more enlightened, who knows.

GRAHAM: What do you like, or not like, about living in Los Angeles as a writer and artist?

ALIC: I worked really hard to be able to move to LA and stay here, so I have this immigrant humility and gratitude that colors my entire experience of being here. Even my worst days offer this consolation of, “at least I’m in Los Angeles.” When you grow up in Canada, America is this mythic place that only celebrities and millionaires can move to. You’d take a day trip to Niagara Falls and be like, wow, I’m in America. It’s been eight years and I’m still walking around like, wow, I’m in America! So cool! Figuring out how to live here on my own gave me the confidence to pursue bigger things.

Most of my friends [here] are musicians and visual artists, and being surrounded by them helped accelerate my own creative ambitions. There was a safety to not being in the [center of the] literary world, too. I didn’t know any other writers, so I could just do my own thing. I had the freedom to experiment [with writing] without the pressure of turning it into a career. Writing professionally hadn’t even occurred to me; I was still driving three hours a day to and from my shitty office job and writing on the weekends. I think if I lived in New York, I would have been too affected by the competitive energy. Whenever I’m there I feel exhausted and out of place and I don’t know what anyone is talking about. I need to go home and sit in a dark room alone for a while to recover.

GRAHAM: Since the pandemic, my reading habits have changed so much—I have a much shorter attention span and much less patience, and I won’t stick with something for more than about fifty pages if I don’t find it compelling. I’ve found it a bit more difficult during this time to find books that grip me throughout, but yours did. It is literary and cerebral, but it’s also incredibly fun, and funny, and uplifting, which feels like the best kind of medicine right now.

ALIC: Thank you so much. I try not to ever take myself too seriously, and I knew I wanted to write something light and fun and enjoyable. A lot of people conflate Serious Art with trauma and darkness, and there is a lot of great art that emerges from pain, but humor and silliness feel just as holy to me. Life can be so brutal, and humor can really soften the blow. I can see how it can be a defense mechanism too—my inability to be purely earnest without adding a little wink to everything. I admire people who have to courage to write honestly about their lives. I know some people say art is not entertainment, but I really tried to entertain. I really considered the reader’s experience, and I wanted it to be joyful.

GRAHAM: Would you say there’s an idea or theme that’s emerged in your work, or something you keep circling around?

ALIC: Broadly speaking, Bad Thoughts deals with women who are sort of stagnating at the precipice of a threshold, stuck in their own thoughts, feeling estranged from themselves and the world. I recently read this book called Puer Aeternus (Latin for “eternal child-god) by the Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz, who coined the term “Peter Pan Syndrome.” She mostly writes about men, but briefly mentions the female version of this archetype, which is called a “Puella.” These women resist crossing over various thresholds to adulthood, namely the more heteronormative milestones of marriage and motherhood. This represents a bigger resistance to confronting their own mortality. Especially with motherhood, which is the ultimate death for a Puella. As much as it is expansive and generative, it reduces a woman to her earthbound body. Her body undergoes a transformation, and she emerges changed. She becomes a new person with a new life. But who will she become? What is that life? I’m not making any moral judgements for or against, I’m more exploring the anxiety that comes with this human experience.

That anxiety has been amplified by the fact that we now conduct a large part of our lives online, on screens—it allows for this more disembodied experience of reality. We can happily live in the domain of the mind and of our online personas. There are many valid reasons for feeling stunted, or even disenchanted with the prospect of “growing up.” There’s a pervasive nihilism and hopelessness [when it comes to thinking about] the future; [sometimes even] an inability to imagine a future. I think a lot of people assume that only men grapple with [this], and women are just waiting around for them to get their shit together and give them a baby—but women struggle, too. Taking anything from the realm of the imagination or spirit into the material world is scary and limiting—like putting out a book. It’s a kind of baby. I can’t control what will become of it, and maybe that’ll be good for me.