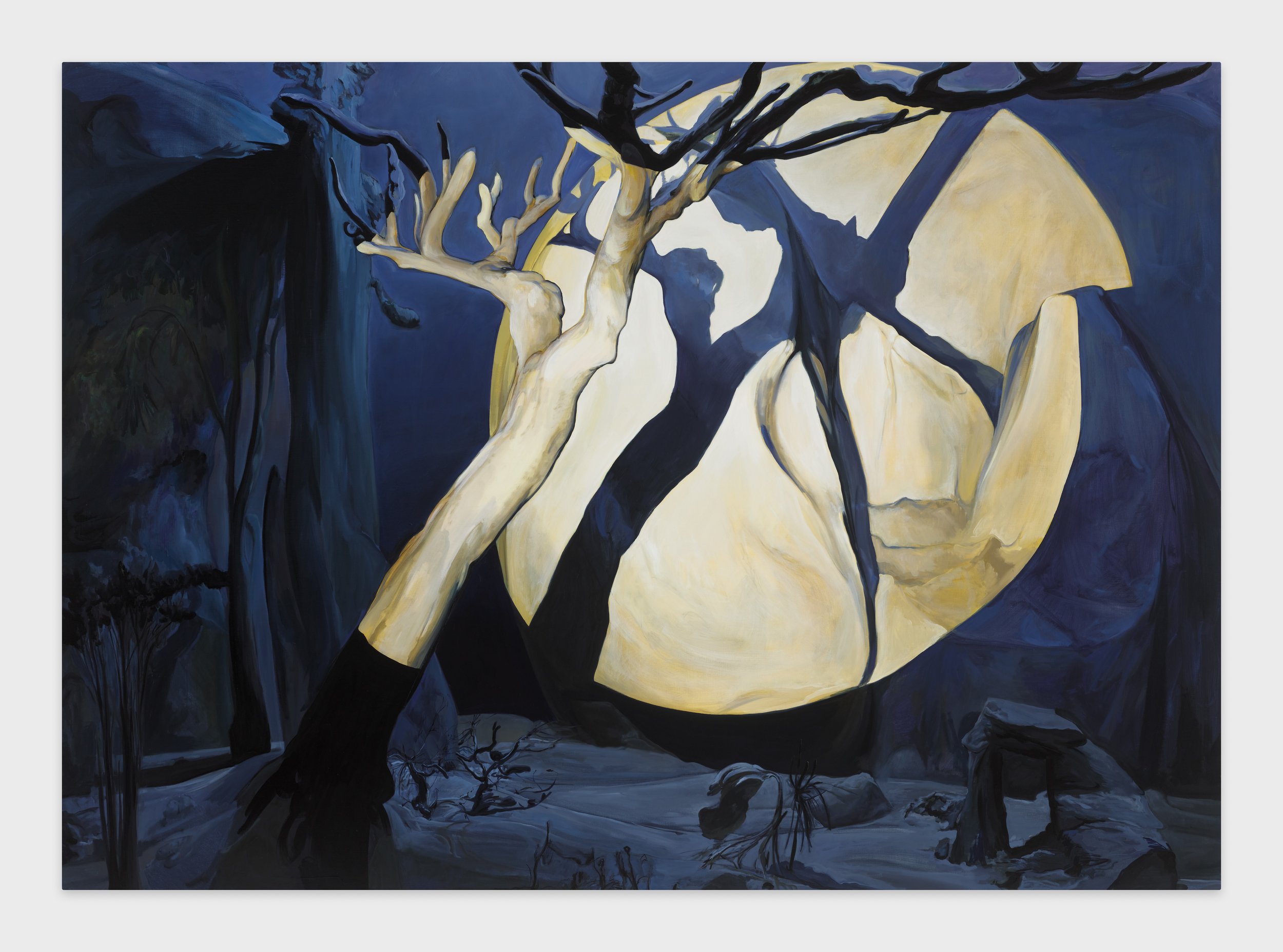

Photo by Genevieve Hanson

text by Karly Quadros

The beginning of May in New York is time for Frieze: time for smart, clipped suits, time for well-to-do collectors, and time to pack into the vaguely dystopian honeycombed behemoth known as The Shed. And then, there was Jeffrey Deitch.

On May 3, a cavalcade of artists, burlesque stars, magicians, drag queens, sword swallowers, latex fetishists, fan dancers, scenesters, and bright young things stepped right up for the night of all nights, the show of all shows, a spectacle to bring even the stodgiest gallerist to their knees: a carnival. Presiding over the whole thing was master of ceremonies/artist Joe Coleman, who curated the group show and contributed a variety of artifacts from his own personal Odditorium of historic circus curios. The gallery was packed tight with art and packed even more tightly with people. A glimmering merry-go-round twirled next to a bulging, fleshy sculpture and ornate Coney Island mermaid costumes. The over forty artists invited to participate ranged from big chip favorites like Anne Imhof and Jane Dickson to cult favorites like Kembra Pfahler and Nadia Lee Cohen to contemporary favorites like Raúl de Nieves and Mickalene Thomas to historic figures like Weegee and Johnny Eck. Coleman, a lifelong devotee of the carnival and performing arts, made a point to include and celebrate the work of circus arts performers that have made up his own found family for decades.

‘Circus’ is a word often used to evoke a sense of chaos and farce — a political circus, a clown show — but the festival of carnival, which is celebrated in more than fifty countries around the world, has a more subversive history. The elaborate masks, headdresses, and costumes that have made carnival celebrations in places like Venice and Rio de Janeiro so iconic were a way of turning the daily socio-political order on its head. Class, gender, sexuality, and power were turned on their heads and marginalized communities, enslaved people and queer people especially, were able to express themselves with more freedom in public.

The American circus tradition is deeply troubled by its own abuses against people of color, disabled people, and animals, but it is undeniable that circuses were also alternative spaces for survival and community for those who couldn’t or weren’t allowed to live freely in mainstream society. In many ways the carnival, with its wild exuberance, unabashed sexuality, hair-raising feats, ramshackle opulence, seedy thrills, and thicker than blood bonds is the ultimate expression of the found family. We caught up with curator Joe Coleman to talk more about the exhibition, flea circuses, Times Square’s sleazy history, roadside attractions, and more.

QUADROS: It's Frieze week right now, so things feel a little more buttoned up, which is why I feel like the show coming out at this point in time was so refreshing.

COLEMAN: Well, these people are like family, so it just comes naturally to me. Some of them, like Jo Weldon produced a work of art for the show, and she had never made a work of art before. Her piece was amazing. People like Bambi the Mermaid have been in the art world for some time. I put some of her costumes in the show because the Carnival is the burlesque house. It's the [Coney Island] Mermaid Parade. It’s Mardi Gras. It's the old Coney Island Wax Museum. It's Times Square back in the day. It encompasses all those things, at least in my imagination. So I wanted to bring everybody on board.

QUADROS: Why Carnival? What is your personal relationship to the circus and who are some of the first artists you reached out to?

COLEMAN: My connection to the carnival dates back to childhood. I was born in Connecticut near Bridgeport, where PT Barnum had a home. As a child, I went to to the Barnum Museum. And when I was very young, I took my first trip to New York, to Times Square where I saw these huge posters of burlesque performers on the street.

QUADROS: Back when it was a little seedy. (laughs)

COLEMAN: Yeah. That's what was fascinating to me, especially as a child. It seemed like those women were eighty feet high on those billboards, plus I got to peek in and see what they were doing. I was also brought to Hubert's Museum where there were sideshow performers and a flea circus. From that day on in my childhood imagination, that was the place I wanted to live. So, when I was in my late teens, I moved to New York, and it’s never disappointed me. I've lectured and performed in Coney Island, and certainly it's been the subject of my paintings. I also have quite a large collection of artifacts dealing with wax museums, sideshows, burlesque and I've included a lot of my archive in the exhibition as well.

Photo by Genevieve Hanson

QUADROS: What inspired you to start collecting?

COLEMAN: It’s really an indescribable urge that you find, or maybe it found me. I didn't find it (laughs). It’s wanting possession of me. Certainly there's a lot of contemporary art that's inspired by the sideshow and by burlesque and even the flea circus people. I have a whole section on miniatures in the exhibition. But aside from the contemporary artists, I wanted the real artifacts and artisans to be appreciated too. There is a real flea circus in the exhibition. There's also works by people that have actually been a part of the carnival. People like Camille 2000 who was an amazing burlesque star from the ’70s ’til the 2000s. There’s one of her great costumes in it. And Liz Renay, also a great burlesque star, author, and filmmaker—she’s in John Waters films, but she also did some B-movies in the late ’50s. Some of her paintings are on view as well. Also, Johnny Eck—have you seen the movie Freaks?

QUADROS: Oh yes.

COLEMAN: He was the Half Man in Freaks who was very charismatic, probably stole the whole movie. He was a fascinating artist himself, so his screen paintings are on exhibit. He was famous for his painted scenes that went into windows and door frames. It was unique folk art. In Baltimore he also made puppets and put on puppet shows. Those and his train are on view. One of the ways he made money was by running this miniature train for children.

QUADROS: That sense of found family is so clear. One of my favorite books is Geek Love by Katherine Dunn. So much of that book is about this deep bond between self-created circus freaks. Can you talk a little bit about that concept and how it manifests in the show?

COLEMAN: Katherine Dunn was a good friend, and I also love that book. I mean, when you find each other, you just get each other. I've seen so many performers rise up in the ranks in Coney Island, and they’re all dear family. Whitney and I have been married for twenty-five years now and our marriage was really a carnival-style marriage. We were married by a ventriloquist dummy named Dutch. He's on exhibit at the gallery as well.

Our wedding was attended by many circus performers and artists. I arrived in a hearse inside of a coffin, and my six groomsmen pulled the coffin out of the hearse after it backed into the barn at the American Visionary Art Museum. They walked a New Orleans-style funeral to the altar, placed the coffin up, and I came out of it and went for Whitney. (laughs) You can also see on display our coffins that were made in Ghana. There's this fantasy coffin tradition, where if your favorite thing is a martini, you can have your coffin made into a martini.

QUADROS: Were there any sort of unexpected additions to the show?

COLEMAN: Walton Ford produced a new work just for the show, which I was thrilled to get. Also, John Dunivant produced a new work for the show, and Mu Pan, and several people that I just reached out to were so sweet to give something to the show, like Robert Williams and Guillermo del Toro. I had pretty much everybody I wanted in the show.

QUADROS: Carnival itself originated in Europe and then was taken to the Caribbean as this tool for political expression. It's a time when common people can wear costumes and speak the language of the ruling class to mock and criticize them. Were you thinking at all about political critique when organizing the show? Or did anyone bring a piece that brought that to life for you?

COLEMAN: Certainly. There's several works that deal with that. One in particular that I was really blown away by is Jo Weldon's piece. She's very well known in the burlesque community, but she's also a sex worker and very unapologetic about it. She made a doll. There's a whole section on dolls in the exhibition that includes Kembra Pfahler’s dolls, but Jo Weldon's doll represents the history of sex work. It's a pretty dramatic and incredibly personal, controversial piece. She's also spoken at the UN about the rights of sex workers. She has such a powerful voice.

QUADROS: Back in the day, the circus really had the power to shock and disgust. People would go to freak shows and pass out in astonishment. These days, I feel like there’s a real sense of over exposure. People are exposed to so much online that they feel calloused, but are there ways that the circus can still shock us? Obviously, you mentioned its power to jostle up people's preconceived notions about sex work, but is there a power to the circus beyond shock value?

COLEMAN: Yes. Obviously there's things beyond shock value, though whether it can change things or not remains to be seen. But it has its effects on people. If you get under people's skin and they take something with them, that's enough. There's all kinds of expression in this show. It’s nice that it could be fun and wild and serious and scary at times. That's what I always liked about carnival. It’s scary and exciting and sometimes it teaches a lesson.

QUADROS: Maybe you're a little repelled by it, but you're also very attracted to it at the same time. It's very frank about some of our deepest desires; the kinds of things we don't want to face.

COLEMAN: There's something wonderful about that—to have a place where you can experience those things.

QUADROS: I'm also interested in the circus as a non-traditional history of America, or the alternate history of the outlaws, the conmen, the thrill seekers. So many of our enduring myths of the country come from the circus, like Barnum and Bailey or Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. What makes that so enduring and timeless?

COLEMAN: It was important to have people that have actually been an active part in some way. Like in the case of John Dunivant—he’s an accomplished artist, and that seems enough reason to have him in the show, but what you may not know is that he created Theatre Bizarre in Detroit, and it's one of the most amazing spectacles of carnival or circus in the past twenty-five years. For many years it's been in this Masonic temple with so many rooms that you get lost. You can't even see the entirety of theater. There’s ghost trains inside, burlesque stages, and art everywhere.

QUADROS: That reminds me of like the House on the Rock or something like that. These American people that just get an idea in their head and create their fantasy world.

COLEMAN: Yeah. And that’s what carnival is all about, really.

QUADROS: Manifesting your dream world.

COLEMAN: Yeah. If there’s something in the world that you always wanted, and it doesn't exist, you have to make it yourself.

QUADROS: But then, there's also the thornier history of carnival. It's always been this haven for the marginalized, but it has also historically been a place where racial stereotypes are reinforced. When you were curating the show, how did you reckon with that?

COLEMAN: There's certainly works of art that deal with it, like Narcissister’s work. She's got one of the most powerful sculptures in the show. Or there’s Derrick Adams’ Ferris Wheel image. I think it's better for them to talk about those works themselves, but it's definitely a part of it. Exploitation has always been a part of the carnival.

QUADROS: In many ways it's part of the art world too. These are ongoing questions about spectacle and viewership.

COLEMAN: Exploitation can certainly be found throughout America in various ways. Really throughout the world.

QUADROS: Do you have an especially unique piece from your own collecting from the historic archives that's in the show that you want to talk about?

COLEMAN: The most unique and rarest one is a ticket to the Tammany Museum, which was the first real dime museum. It predates Barnum; it’s from the late 1700s. Barnum's American Museum eventually took over the Tammany Museum site, so this predates the whole tradition of the dime museum and the sideshow itself in America. And I have an actual ticket to the Tammany Society. You had to become a member in order to see the museum, which consisted of wax figures, taxidermy … you know, what people are making at sideshow museum’s today is pretty much based on what was set up at the Tammany Museum.

QUADROS: What a historic artifact. But then, you also have this flip side, right? People mostly think of the circus as something historically situated with traditions like burlesque that have been around for so long. But you also have some pieces that incorporate new technologies, like the interactive Nadia Lee Cohen piece. Was that something you intended to bring in?

COLEMAN: Yeah, that’s a really great piece. It blew me away when I saw it and interacted with it too. It's one of the most powerful pieces and I think the Carnival would've always wanted to grow with technology, so that does not seem to contradict it at all. When motion pictures became popular, the first places that really started showing them were dime museums and sideshows.

Nadia Lee Cohen, Entitled, 2025

Silicone, sheet metal, and glass

QUADROS: There's something very tactile about that world. Everyone instinctively knows what the aesthetics are.

COLEMAN: Yeah, but Nadia's piece does prove that the technology works really well with the subject.

QUADROS: People think of Carnival as being relegated to the past, but we still get it peeking through into popular culture every now and then. What does Carnival look like in modern times?

COLEMAN: I think it looks like Jeffrey Deitch's gallery right now.

Carnival is on display at Jeffrey Deitch in New York until June 28.

Photo by Genevieve Hanson