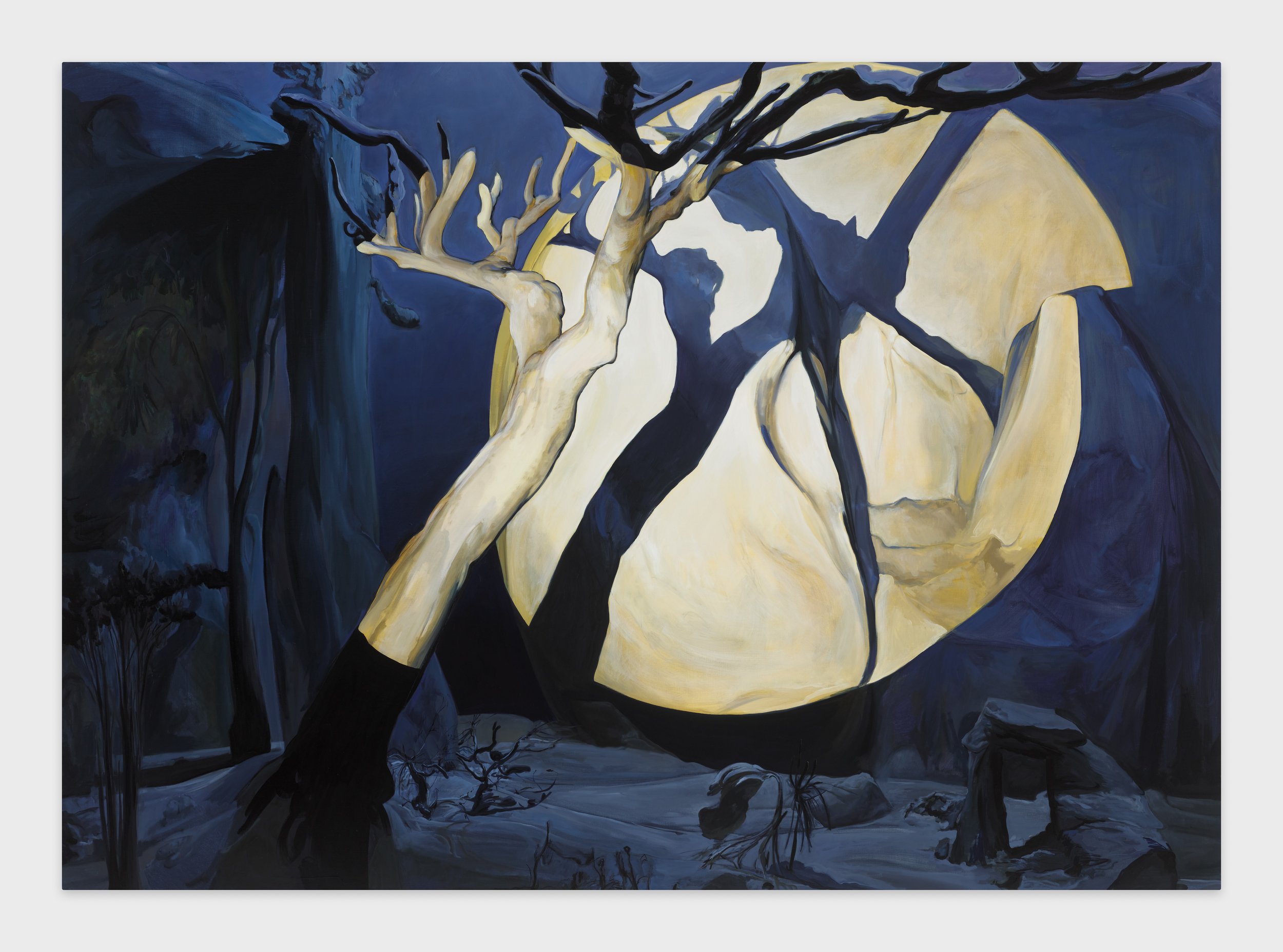

Emma Webster

The Rehearsal (Harvest Moon) (2023)

60 x 84 in

Oil on linen

interview by Chimera Mohammadi

How does one go about staging a stage? Emma Webster’s upcoming exhibition, Intermission at Jeffrey Deitch, answers this question by erasing the line between prop and (back)stage. This boundary erasure is nothing new for Webster, whose work combines the supernatural, unnatural, and natural realms, merging this paradoxical triad into a cohesive, uncanny space that reflects the inescapable presence of human viewership on nature and art. Her landscapes exist in a variety of intermediary spaces: between heaven and horror, nature and technology, fiction and reality, and theater and visual art. In Intermission, she gives physicality to these liminalities while highlighting previously behind-the-scenes sculptural stages of her process, creating an environment of borderless voyeurism that invites us, the viewers, into her creative world, while reminding us of our separation from it, reinforcing our roles as witnesses.

MOHAMMADI: In your artist talk at Perrotin Tokyo, there were a few people asking, “where are the humans?” Which I thought was kind of funny because all your landscapes are very human, in my opinion. What human stories can be found in your work?

WEBSTER: Maybe an Edenic origin story. I've heard many recently talk about the golem myth (or Pinocchio) with respect to AI. Maybe the creation of man, and the animation of this golem, relates to landscapes too because we associate nature is a womb-place. Everything from the Earth.

MOHAMMADI: Your work has been described as otherworldly, supernatural, liminal—does it occupy a fairy tale or folktale niche?

WEBSTER: If we're presented with a backdrop and a stage, it begs the question of what's unfolding. And I'm interested in theater because it's another way, like fairy tales, of creating a suspension of disbelief. Whenever we go into a theater, we're expecting to be surprised.

MOHAMMADI: Do you want to talk a little more about the expanding presence of theater and theatricality in your work?

WEBSTER: The paintings come from staged dioramas in the computer. Usually, the stage is a real device we engage to see an unreal thing. But here, even the theater is a prop in and of itself. It's not a real theater. There’s levels of immersion: the experience of sculpting the source material in the VR, and you also have the immersive experience of being in the black box where you can be transported anywhere. But on top of that, you have to meander through the installation maze of wings, props, and equipment in order to see the paintings. I'm hoping that even the props that make fantasy are still fantasy here.

MOHAMMADI: You’ve talked about dolmens in your work and how you stumbled upon that type of structure accidentally. They kind of double as theaters in your work. Was that combination of theater with these very primal structures conscious?

WEBSTER: That linkage between theater, vitrine, shelter, is all rooted in ‘the box.’ And the dolmens tripped me out when I began to think about the architecture that holds fantasy. It's a place to witness. You can't have theater unless you have spectatorship.

MOHAMMADI: Someone said that “each finished work is a window into your virtual world.” Does each piece feel like a window into one world or are they sort of separate?

WEBSTER: I typically think about them as distinct worlds because each source sculpture is different. However I also like to think about the Jungian subconscious as a physical subterranean root system. When I consider that sort of framing device, it's fascinating to think these places are from one world. An ecosystem that allows for many kinds of life.

MOHAMMADI: You've discussed the universality of beauty and utopian ideals, and you touched on this earlier when you were talking about representing both the Garden of Eden and the fairytale nightmarescape. Do you paint utopias?

WEBSTER: I don't think utopias contain action. My knee-jerk response is “Well, utopia is peace, right? Utopian spaces, the grass is greener, the water's chill.” Anytime there's action, it's like, what the fuck is going to happen? So, maybe they're transforming into utopias or away from utopias, but there's too much tension in my paintings.

MOHAMMADI: Also in the Perrotin talk, people kept asking you about the violence in your paintings, which I thought was interesting because I never got violence from them.

WEBSTER: People read violence when there's an unknown. Violence is a response to fear. I’m coming to terms with our inability to anticipate reality. So much of our world is dramatically transforming right now. John Martin is one of my all-time favorite painters. I still don’t know how he painted the end of the world when the apocalypse, the spirit kingdom crashing into the Earth, is so abstract. How the hell do you make that painting, right? I want to bring that quality of solidifying something that we can't fathom.

MOHAMMADI: There's always fear with new technology, but there's a threat of replacement [with AI] that wasn't there with previous technology.

WEBSTER: Totally. I've been thinking a lot about the show title, Intermission, because it’s a break where you go back to the real world, you're unsure, you've just been exposed to the primary conflict, when the curtain suddenly comes down. You're just waiting. You don't know what you're meant to do. Painting is all about frozen time too. And with developments in AI, we’re waiting for resolution. We're all just waiting for an answer.

MOHAMMADI: You’ve been compared to everyone from Bierstadt to Dr. Seuss, and you've cited Blake and Bosch as among your influences. What were some inspirations for your upcoming show?

WEBSTER: Adolphe Appia, old theater productions, and silent movies, for simple lighting compositions. In this show, I’m presenting landscape as prop. Some of the artists that you brought up, Blake, John Martin, or Turner, I'm fascinated with how they inject spirit into structured scene. This is also where I’m at mentally, existentially, in this place where spirituality and science merge.

MOHAMMADI: Will theater become a stronger theme in your work?

WEBSTER: Yeah, I mean, everything is theater in its own way. It's a simulation. And it's linked to still life in that way. This is the first show that I've done something this immersive. It's one thing to engage with sculpture. It's another thing entirely to show the behind-the-scenes, literally have people stumble behind the scenes, and have points of reference for the paintings that have previously been secret.

Intermission is on view through October 21st at Jeffrey Deitch, 7000 Santa Monica Boulevard, Los Angeles.