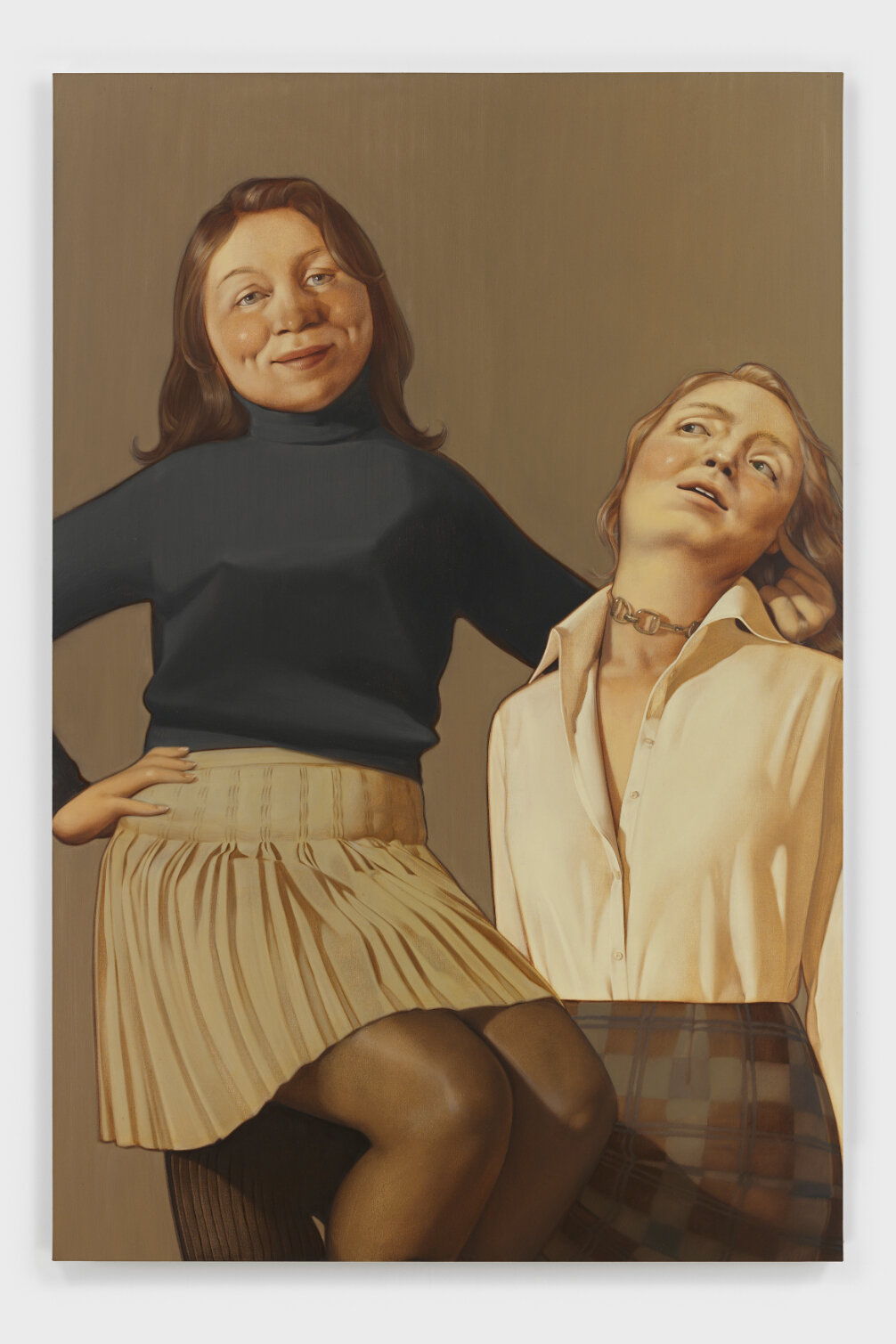

Painter Ireland Wisdom speaks with longtime collaborator Carlye Packer about the sensual rituals of portraiture, the psychic tension of play, and why painting from life is an affair of devotion, desire, and death.

portraits by Austin Sandhaus

In this intimate conversation between gallerist Carlye Packer and painter Ireland Wisdom, what begins as a reflection on their creative partnership unfolds into a meditation on intimacy, eroticism, play, and mortality. Wisdom, whose portraits are painted from live models in prolonged silence are charged with a psychic intensity. She speaks with Packer candidly about her relationship to the body, desire, and the mythic tradition of being seen—and of seeing. As they revisit their early collaborations and look closer at Wisdom’s new Dance Macabre series, the dialogue dances between the sacred and the scandalous, from Goya to Dorian Gray to Georges Bataille. As friends and colleagues, they muse about works that are made like someone chasing the moment before it is lost. Whether you are a sitter or simply a viewer, you are invited to enter that entanglement with her.

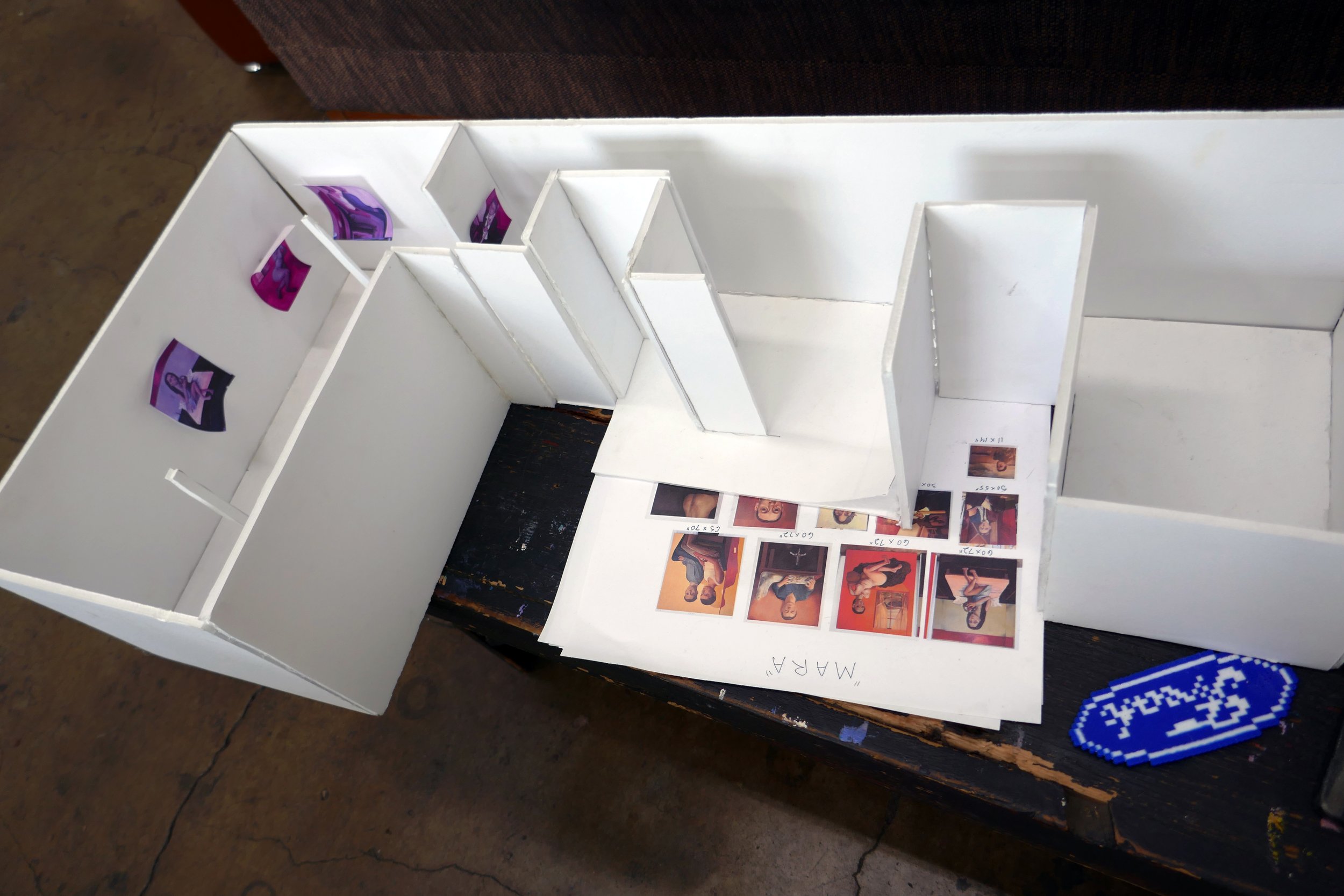

CARLYE PACKER: Okay, so it is a pleasure to be interviewing you. We have known each other for over ten years, and started working together about three years ago when I did your first major solo exhibition at my old gallery location on Sunset, which was the original American Apparel flagship store. That exhibition was presented in October of 2022 and was an exhibition of how many portraits? Twelve?

IRELAND WISDOM: Twelve portraits and two still lifes.

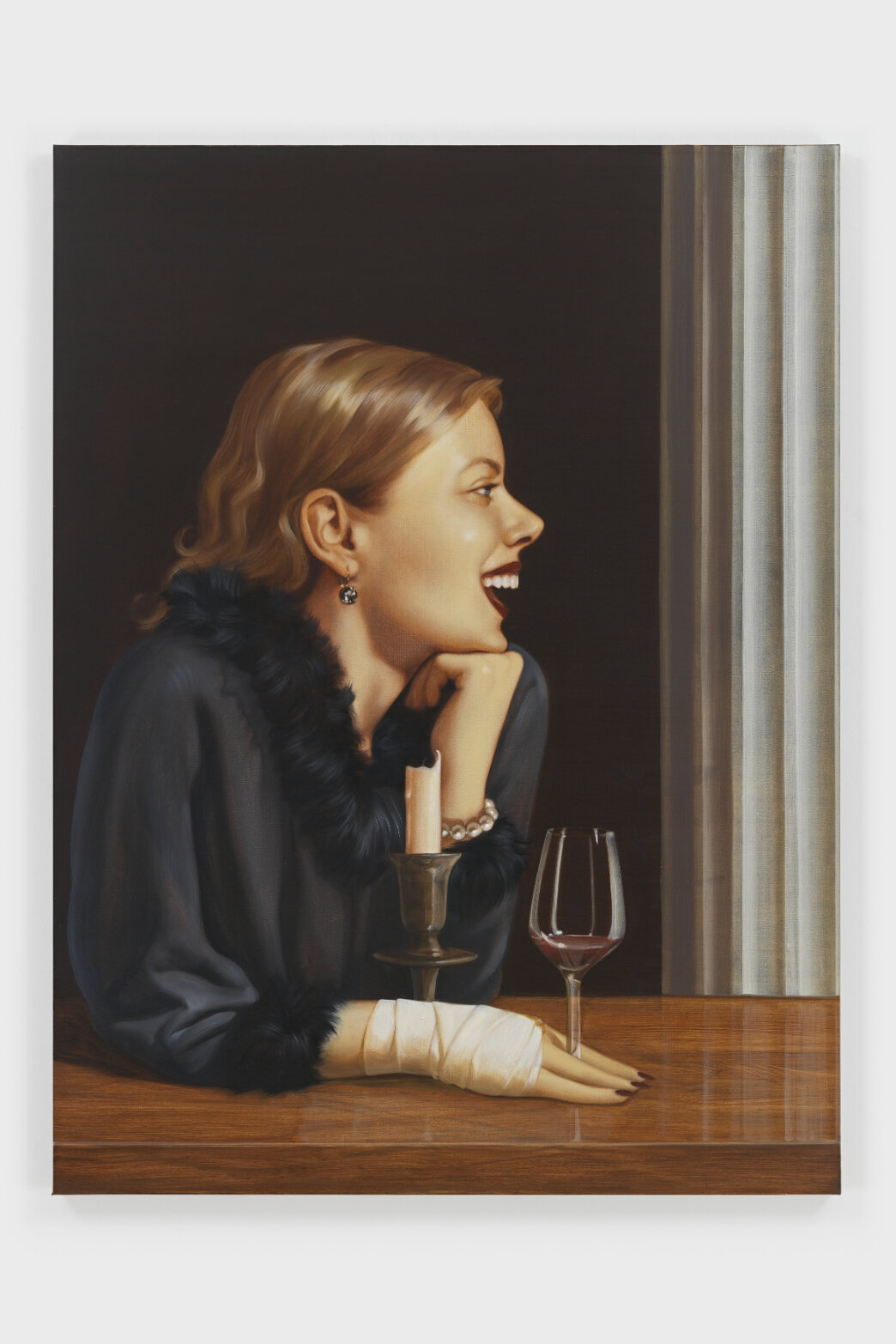

PACKER: Yes—all set against a black Goya-esque background and all painted from live models, right?

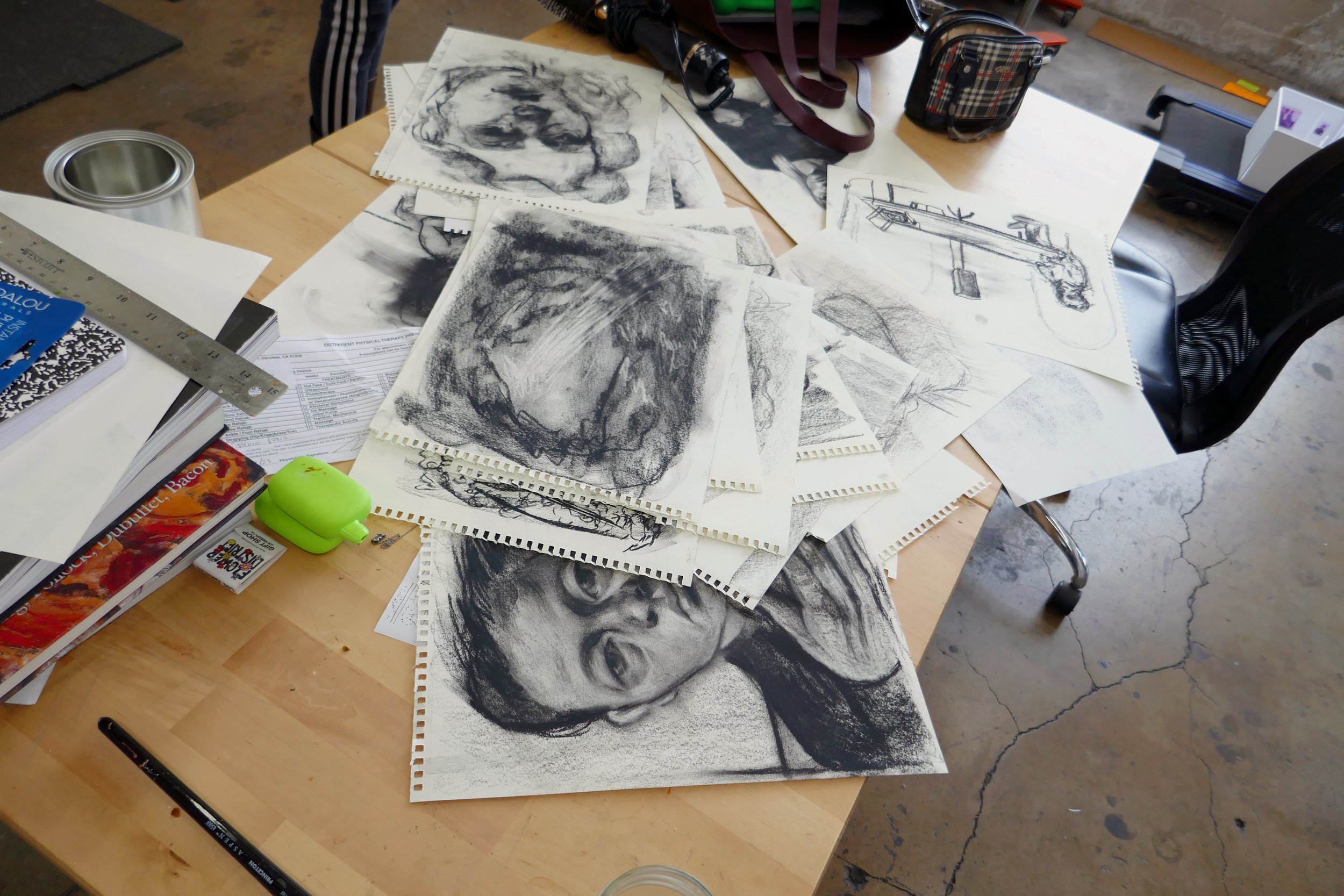

WISDOM: Yes, I was trained in Florence on how to paint from life, using an old technique that started with Leonardo da Vinci called “sight size,” which is painting a figure or anything really in the scale of life. It was a technique that was sort of brought back to life by John Singer Sargent in the 19th century. So I have continued carrying out that really old tradition, I continually choose to paint from life with my models sitting in front of me.

PACKER: A lot of your paintings tend to be very sensual, with direct eye contact, mostly nude or semi-clothed. As a viewer, there is obviously a very deep connection between you and the subject being painted—what is that relationship to your subjects and your relationship to painting them and their relationship to you as they are being painted?

WISDOM: Well, desire has always been linked to themes of love and intimacy, a yearning between two figures. In choosing a model and them accepting my request to paint them, there is a sort of bond of intimacy established.

PACKER: How is it that you choose your models?

WISDOM: So, usually it just comes from an impromptu feeling of inspiration. Either it's a close friend that I've known for years that has been a consistent muse or it's another type of instant attraction to an unknown person—someone that just kind of wows me, who grabs my attention, someone who feels iconic, timeless, very slay. It’s a very Dionysian impulse. I’m drawn to the essence of something or someone that just feels memorable and usually I’m physically attracted to them as well, which is why a deep sensuality comes out in my portraits; a kind of intenseness that you can feel within their eyes and their facial expressions, a sort of combination of hunger, lust, devotion or appetite.

PACKER: What actually happens in the process, when you're in-person painting someone?

WISDOM: There's a really interesting dynamic between the artist and the sitter, a very genuine experience that is hard to put into words. It’s like trying to capture the powerful feeling that is the human condition, that of being desired and of desiring another person—it’s like trying to establish a lost object, or a dream once you awake, or the tension between how someone appears externally, their unconscious mind, how I see them, how I want them to be seen, how I want them to be immortalized and how they want themselves to be immortalized, and the tension between those things are all in play—all while they are looking me in the eye, and I’m looking back at them.

PACKER: It’s giving very Titanic.

WISDOM: Yes. (laughs) It’s very titanic, but it’s also very Dorian Gray. It’s an erotic sort of adventure—I mean the experience of being immortalized in oil is a very particular and deep experience. The model basically sits in silence—in a meditative state—which feels like a rare experience these days—to be observed and captured over many hours, over many days—in slowness—especially in this digital era.

PACKER: I have sat for you for a portrait and it definitely felt like a weird out-of-body affair.

WISDOM: It is a sort of affair, there’s something scandalous inherent in this tradition of painting from life. It’s an expression of energy flows and an obsessive concern with the erotic, with myth, with self-mythologizing, the sacrifice of giving one’s self, the nature of excess. It’s an entanglement of energy, a giving and a taking from both sides. I usually choose to paint my subjects looking directly at me, so when it's finished, the viewer looks at the painting and the subject is looking directly at them. The viewer then becomes a part of this entanglement as well.

PACKER: I think one of the best examples of this is your reclining nude portrait of Marco, in his Danskos, with the papaya split open. I feel like when we exhibited that painting, people wanted to know who he was, what your relationship was, and why does he look so good?

WISDOM: (laughs)

PACKER: Someone had actually described, when viewing the painting, that it made them feel hungry.

WISDOM: (laughs) Yes, definitely. It’s giving appetite.

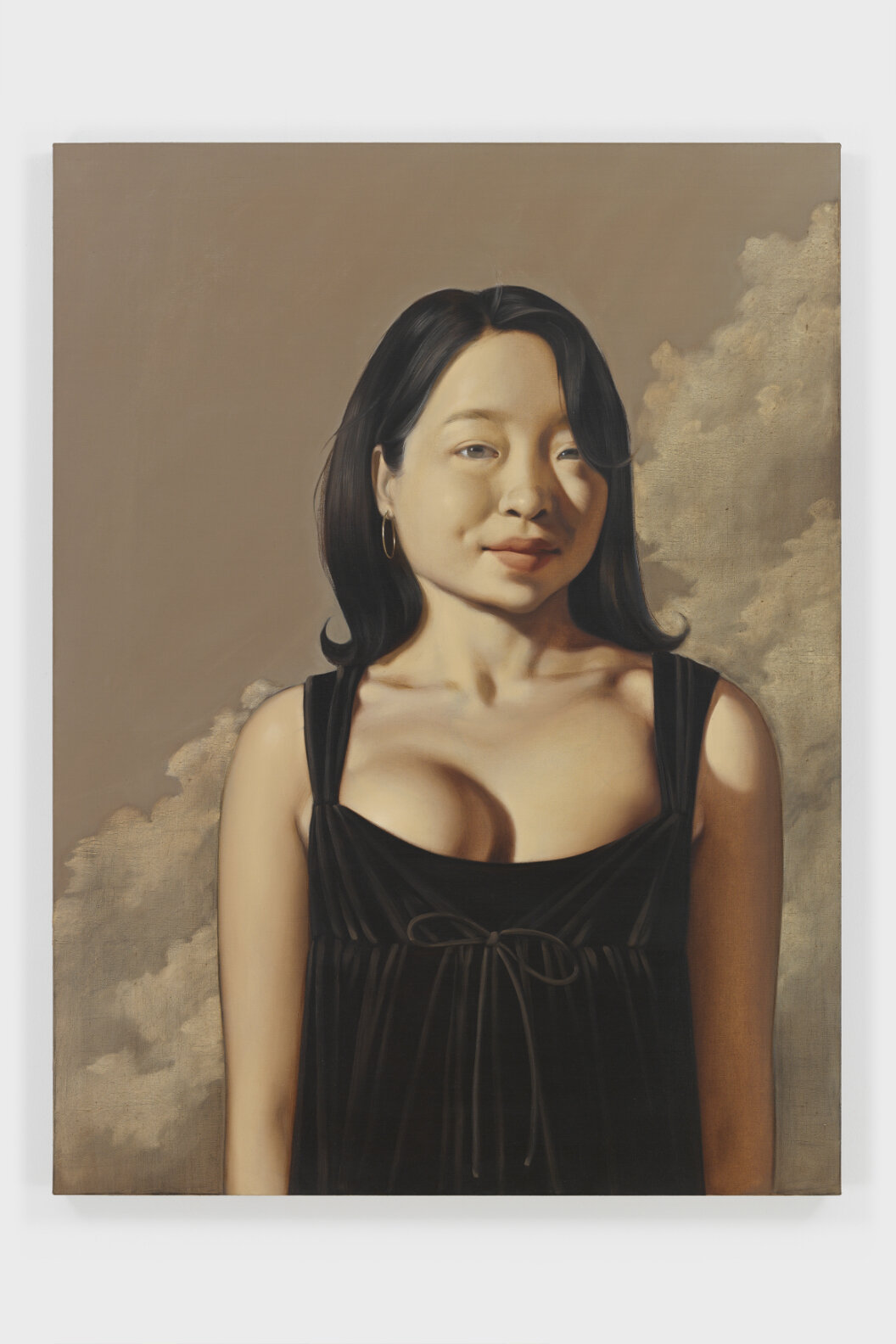

PACKER: Most of your paintings elicit those questions for people. Like when we exhibited the portrait of Yeha (“The Keyster”) at Felix this year, people were so curious to know more.

WISDOM: What did they want to know more about?

PACKER: Everything, really. Whenever I exhibit your work, it demands a sort of curiosity from the viewer.

WISDOM: Yeah, I feel like “The Keyster” was a great infusion of reality and surrealism. Or rather sort of an infusion of the psychic tension between play and its ambiguities.

PACKER: In what sense?

WISDOM: Well, she has her arms open, pointing towards two different keyholes. It kind of symbolizes these basic, everyday decisions we have to make. How it all comes down to which one we pick? And she is standing there, being playful about the decision making process, which is something I think is important for us to remember—it sort of goes back to Bataille's ideas about play—like how he believed that death reveals the impossible and that play is a way of seeing this.

PACKER: Well your new series of paintings is very overtly death-oriented.

WISDOM: Yes, this new series is focused around the Medieval genre of the Dance Macabre, or the dance of death. In the past this was illustrated in a poetic yet literal way, the idea that all are equal before death. Obviously, they were dealing with the black plague back then. Now, in my current series, I’m using a lot of similar imagery, but thinking about death not necessarily in the ending-of-life way, though that as well, but rather as the series of endings that we all go through that make way for new cycles to come. My own personal take is about one having an ego death and dancing with it.

PACKER: Which circles back to the playfulness that is in most of your paintings.

WISDOM: Yes, I find that play is one of the most important things, the muses do keep musing.

PACKER: Who would be your ideal next muse?

WISDOM: I see people all around me that I would love to have sit for me. Julia Fox would be nice, I don’t really know why, probably because I just read her memoir. But I also saw this old man walking today, when I was walking to meet you, and asked for his number, he was serving homage to Jusepe de Ribera. Maybe one of the presidential portraits, not in the near future, but in the far far future, when I’m much older. Or the Pope, that would be iconic.

PACKER: Would you paint the Pope nude?

WISDOM: Only if he let me.