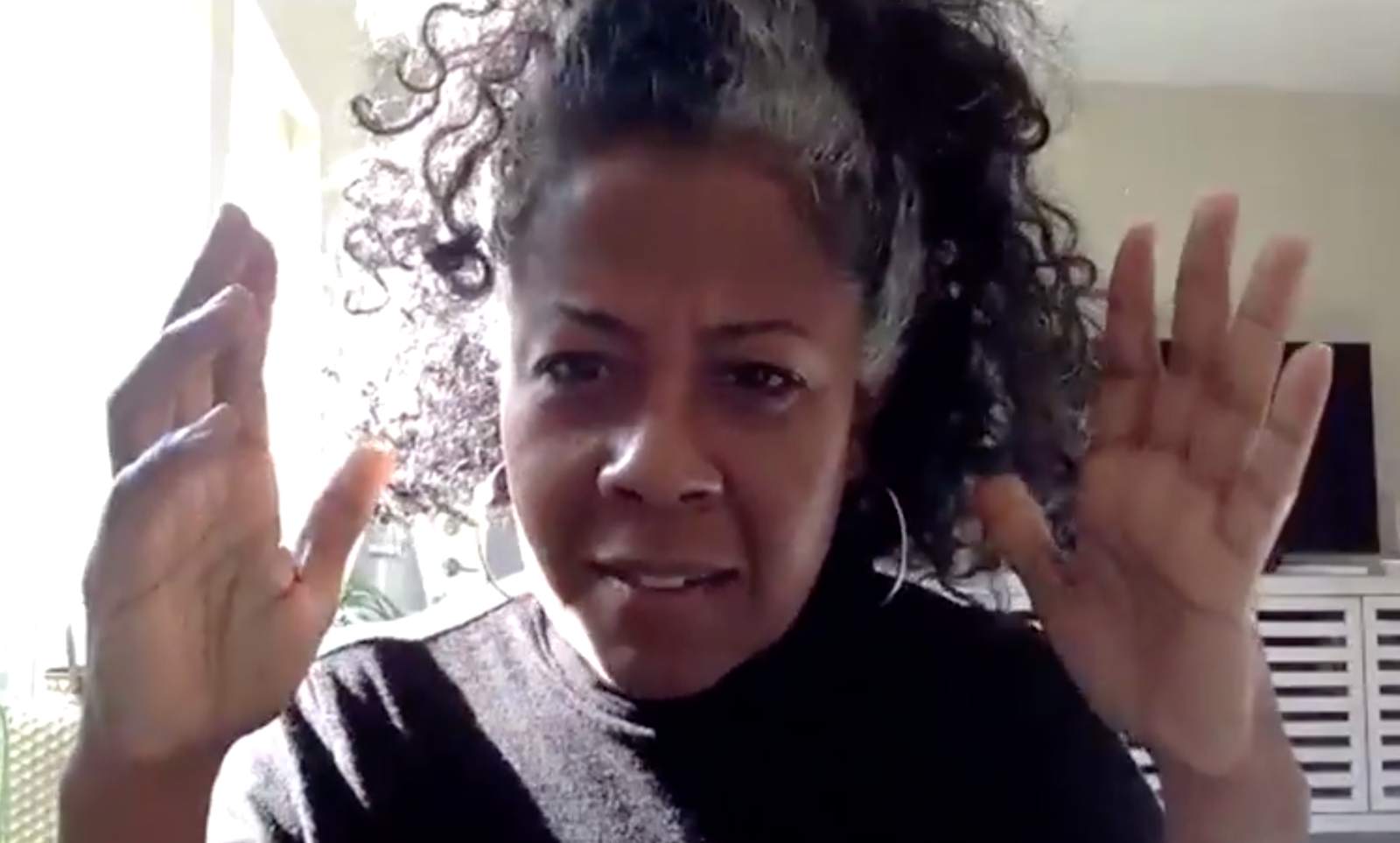

interview by Avery Wheless

portraits by Summer Bowie

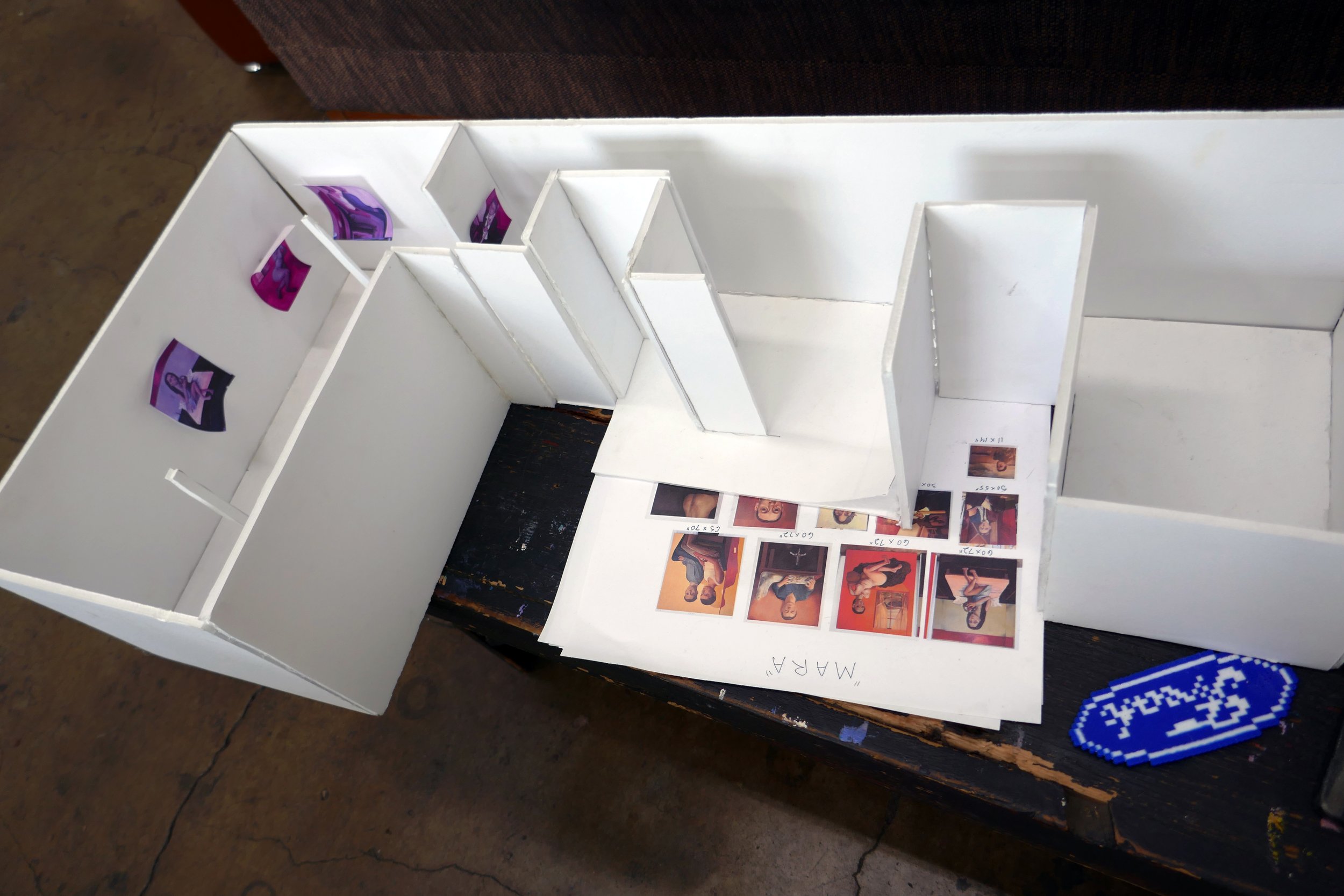

Each and every day we observe thousands of faces online and in person. And with each and every one, we reflexively look for clues to determine how they must feel. It is an empathic impulse endemic to us as social creatures. And yet, regardless of our perpetual, involuntary efforts, we can never be sure that we’ve ascertained any level of truth. It’s this mystery that lies at the heart of Jess Valice’s painted figures. The artist’s initial life path, which was headed toward a medical practice, laid the foundation for an approach to painting that leaves the viewer in a state of quizzical study, lost in the gaze of a subject who was never asking to be diagnosed. The predominant demons and desires of her subjects even seem to elude Valice, as she finds herself reworking each of their faces incessantly until she lands on something that feels honest. For her solo exhibition, Mara, opening today at Almine Rech’s Upper East Side gallery in New York, the subjects in question are at various points of overcoming the part of their egos that obstruct the path to enlightenment. According to Valice, “There is this overwhelming sense of fatigue that I think is typifying our generation, the weight of a spectrum of emotional responses that digital space provokes in us every day… It’s all so complex—this is where the science and melancholia come in—the recognition of this blankness as a widespread response. It’s too much to feel.” Fellow painter and confidante Avery Wheless joined Valice in her studio as the paintings were nearly finished to delve into the making of this new body of work and demystify some of the je ne sais quoi embodied by Valice’s disaffected figures.

AVERY WHELESS: I know you're majorly self-taught, but originally you were on a path of studying neuroscience. When did that shift become apparent to you.

JESS VALICE: I guess it was around that time when the work just got too crazy for becoming a doctor and not necessarily knowing if I would enjoy it or be successful at it, or even have a shot at going to medical school, for that matter. I just realized I couldn't stop thinking about painting. So, when the workload got heavy, I just was like, No, that's it. I'm done. I was painting in between all my courses and all my exams. I mean if you're putting all this effort into something that you don't care about and you're actually getting somewhere with it, then imagine the possibilities of what you can do when you actually pursue something you care about that you want to do forever—something you could never live without.

WHELESS: Do you feel there's any crossover with your studies in neuroscience and psychology—anything that's woven itself into the visuals that you paint?

VALICE: I put a lot of emphasis on the gaze because when I look at somebody just out in the world, or someone looking back at me, I feel like I understand and empathize with what may be going on in their head. It's a weird trait to have. I'm just looking at someone and thinking about their brain chemistry. There’s a beauty in knowing that all of it is different, and you can't actually know what’s going on in someone's head. But you could take a good guess. There's something very humbling about not knowing how another person’s brain works. So, this gaze and this lack of emotion, or micro expression in the faces of the people that I create just tell their own story, but also leave mystery. I want people to know that they'll never truly know, but their interpretation might teach them something about themself.

WHELESS: For this body of work, in particular, you shot friends and other artists, and it was so fun to be a part of that process of getting to sit for you.

VALICE: God, your photo, you were in supermodel mode with my high school friend taking photos.

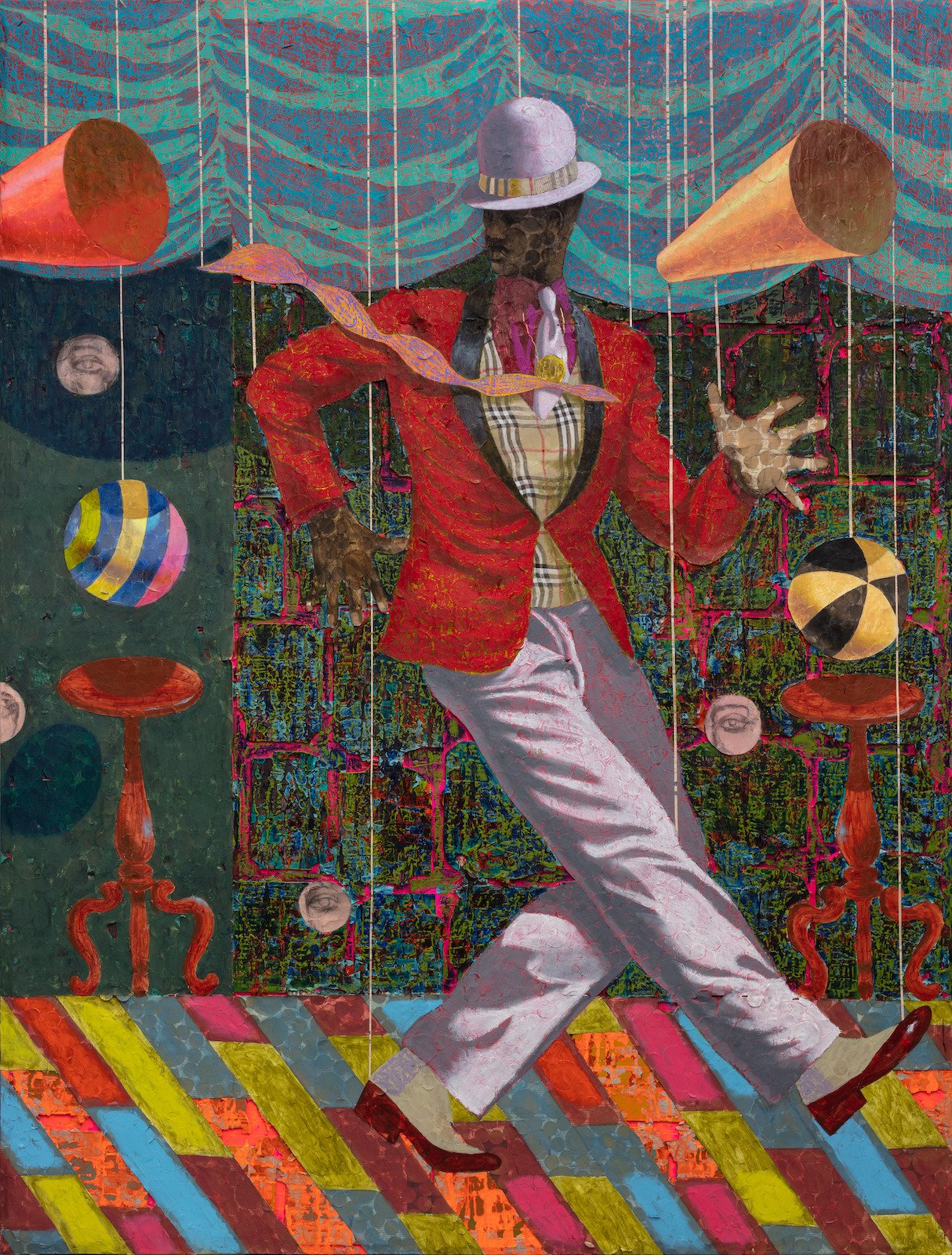

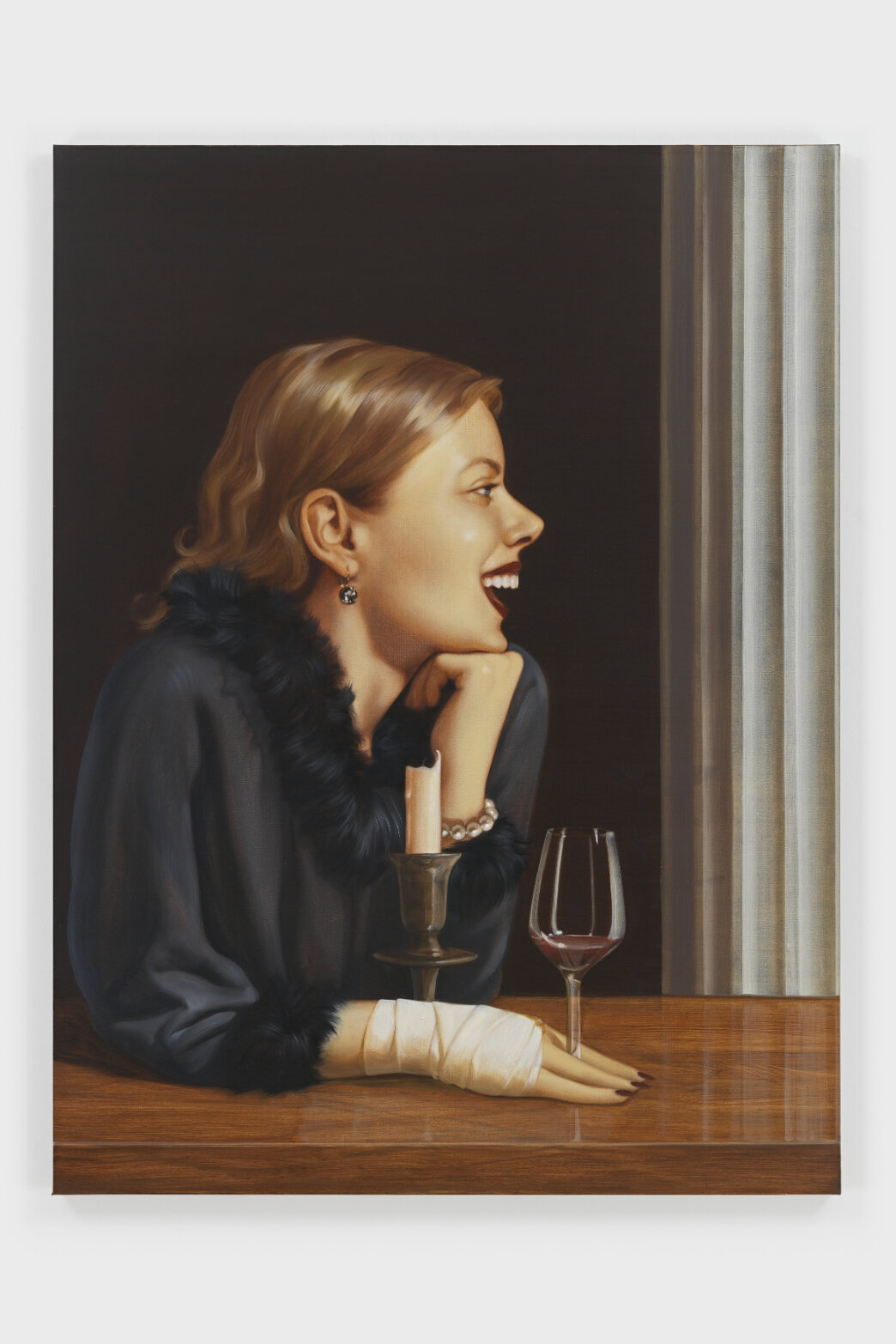

Jess Valice

Mara, 2024

Oil on canvas

182.9 x 152.4 cm

72 x 60 in

© Jess Valice - Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech Photo : Matthew Kroening

WHELESS: It was fun. I felt like we were all entering Jess's world, and Jess's way of lighting, and shooting, and trying to embody what your paintings already have in them—this sense of staring back at the viewer, but also a strong sensuality. Was there something particular you were looking for in the people that you chose to sit for you?

VALICE: The majority of the people that I chose, including yourself, are people I have an emotional connection to beyond just an acquaintance. You and I have shared personal stories. I've shared personal experiences with some of the people that came, and some are people from childhood or school that I have pushed away, but they have stayed with me. That makes me feel this sense of community. It wasn't necessarily anything that was physical, though some of the photos and some of the people have attributes of the faces that I generally like to paint—very sad-looking eyes—but I chose those people for those reasons.

WHELESS: Was that the first time that you shot direct reference models for the paintings in that way?

VALICE: Yeah, That was my first time. It was cool. I appreciate the faces that I just create because these faces all look very similar, and yes, they do look similar to me, but they're fully made up. So doing something with people that I recognize was interesting because I'm connected to all those fake people I create, but it’s cool to be tied in with all the real people in my universe that I create.

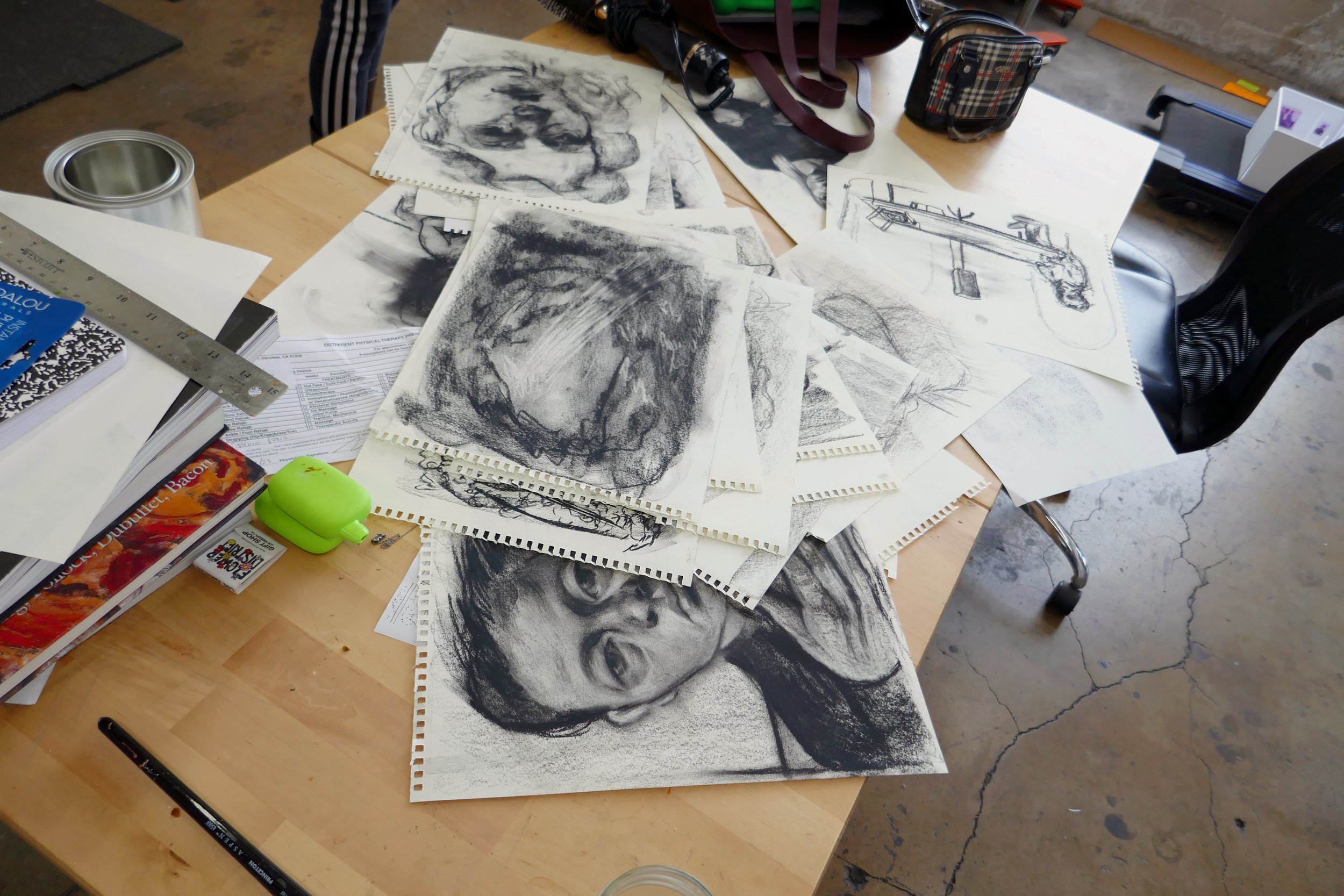

Jess Valice

Sincere Condolences, 2024

Charcoal on paper

35.6 x 27.9 cm - 14 x 11 in (unframed)

44.5 x 36.8 x 3.8 cm - 17 1/2 x 14 1/2 x 1 1/2 in (framed)

© Jess Valice - Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech

Photo : Thomas Barratt

Jess Valice

Self Portrait, 2024

Pencil on paper

35.6 x 27.9 cm - 14 x 11 in (unframed)

44.5 x 36.8 x 3.8 cm - 17 1/2 x 14 1/2 x 1 1/2 in (framed)

© Jess Valice - Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech

Photo : Thomas Barratt

WHELESS: I feel like most of the faces that you painted in the past were centralized around this uniform character with big, deep-set eyes, and the facial features were similar to your facial features. As painters, oftentimes we end up painting ourselves just because we are used to seeing our faces all the time. But, maybe you could talk about how all of that ties into the title of your show…

VALICE: Going back to being self taught, it was really just from looking at religious artworks and Caravaggio that brought me into my interests with being a figurative painter. They have those big eyes—it never was supposed to be me—but you can see a strong resemblance if you do a side-by-side of my faces with that of Caravaggio's figures or Artemisia [Gentileschi]. My boyfriend's mom told me I look like the Virgin Mary in a photo that she saw the other day. So, yeah, it was never supposed to be me, but they are. At times, I've referenced my own face for lighting, and generally, I have the same face as the liturgical figures I reference.

But it does come back to Mara. Mara comes from Buddhism, it’s like your self-centered inner thought that says you don't have to learn anymore. You don't have to take anybody's advice. You don't have to take anybody's word for anything. Whatever you know as of right now is set in stone and you're not going to change your mind. I've always hated that perspective. The gaze that these figures make—I'm staring directly at one of them right now and I want to cry—it's like decision-making, it's them thinking. It's them either knowing what they want to do or not knowing, questioning themselves or questioning the people around them, or lack thereof. I like to use color and light, how melancholy or content they look to dictate which direction of Mara (or not) they would be in.

WHELESS: I've been thinking about the title of the show since you told me about it and I think there's so many reasons why that word probably stuck with you on a psychological level, all the different ways that it filters in and out of your work, whether it's in humor, or in symbolism, or in the gaze. Can you talk a little bit about the environments that you put these figures in or some of the props you paint in them?

VALICE: Well, with you being a painter as well, you fully understand that each work you make is a diary entry, or it can be. Some people don't do that. I definitely am someone who does that. No matter who's in the painting, they, unfortunately, have to take on the responsibility of living within the networks of my emotion. So, each painting has its own moment. They each have another experience I have had, or they're living in a world I'd like to be in, or would like to get out of. There's this orange one of this girl just reclining outside, it has a beautiful view of some town, and she just wants to stay inside. There's decision making in that. Does she like where she is? Would she love to go run out there? I think it's beautiful. Personally, I'd love to go run out there in that field. But then, there's this guy reclining, embracing a plank of wood. He could be longing for something. He could be just wanting to hold somebody and I think that in that time, I did feel that way. I did pose him in that way for the photo. They all have their different moments, yet they all come back to Mara. I rarely ever theme a show. I usually make a show and then figure out what was going on in my life at that point or what I was thinking about when I was in here [the studio] for the past year.

WHELESS: What have you learned now as you've been reflecting on this body of work?

VALICE: You learn something new every time. It could be a therapy session for you, or it could be just your growth as a painter, or just skill developing, which is always helpful too. But you take something away with every body of work.

WHELESS: What's your work-life balance like?

VALICE: Work-life balance…. That's the next thing I need to figure out.

WHELESS: Next project.

VALICE: That's my next project. That's the question of my life. I was talking to Austyn Wiener the other day and she's like, “Jess, just go home and take a fucking bubble bath. Just do it.” I hate baths, so I won't. But she did remind me that I have to make sure that home is as comfortable to me in these times as my studio, because I was expressing to her that I am at the studio more than I am home at this point. Home is really just where I sleep now. I love my home. It's so nice. I mean, it's beautiful. It's a great little spot. But I don't want to be there because I want to be here. But she was helping remind me of the importance of creating that kind of space in order to not lose my mind, which is inevitable with every show, but it could be helpful to fix that side of it. But I'm someone who likes to cold call my friends while I paint, and my family. So, I guess with my social life, it still works out. I love to talk on the phone. So, the work and friendship balance is working out. There's a lot of people I have to text like, Sorry, I'm losing my mind. I'll call you back in a few weeks.

WHELESS: As your friend, I think you do a pretty good job. After making this body of work, or when you think about your paintings in general, once they leave your studio, what is your hope for them, or how do you see them existing?

VALICE: Ghosts

WHELESS: Ghosts?

VALICE: They will be ghosts for sure, from here. I mean, I know some people find them staring back at you a little bit spooky, but I do hope that they exist as romantic images and they become special to somebody. To me, they're my children, so my ghost children.

WHELESS: It kind of ties back into your viewing of religious works as a child. What else do you have in the works?

VALICE: Hmmm, My lobotomy? I'm really looking forward to making new work, so honestly I've been in the studio just constantly. This is the first time in a long time that I've put so much more effort into detail. I'm really excited and looking forward to challenging myself to do things that I haven't done before like I did here like with the landscapes, and just new figures, and understanding color a little bit better. I'm excited to mess around after which I will be jumping right back into painting. Probably when I get back from New York, I'm gonna lose my mind. I have a show next March.

WHELESS: Where's that?

VALICE: In Paris with Almine. I'll be doing some fairs in between that so check in on me every once in a while.

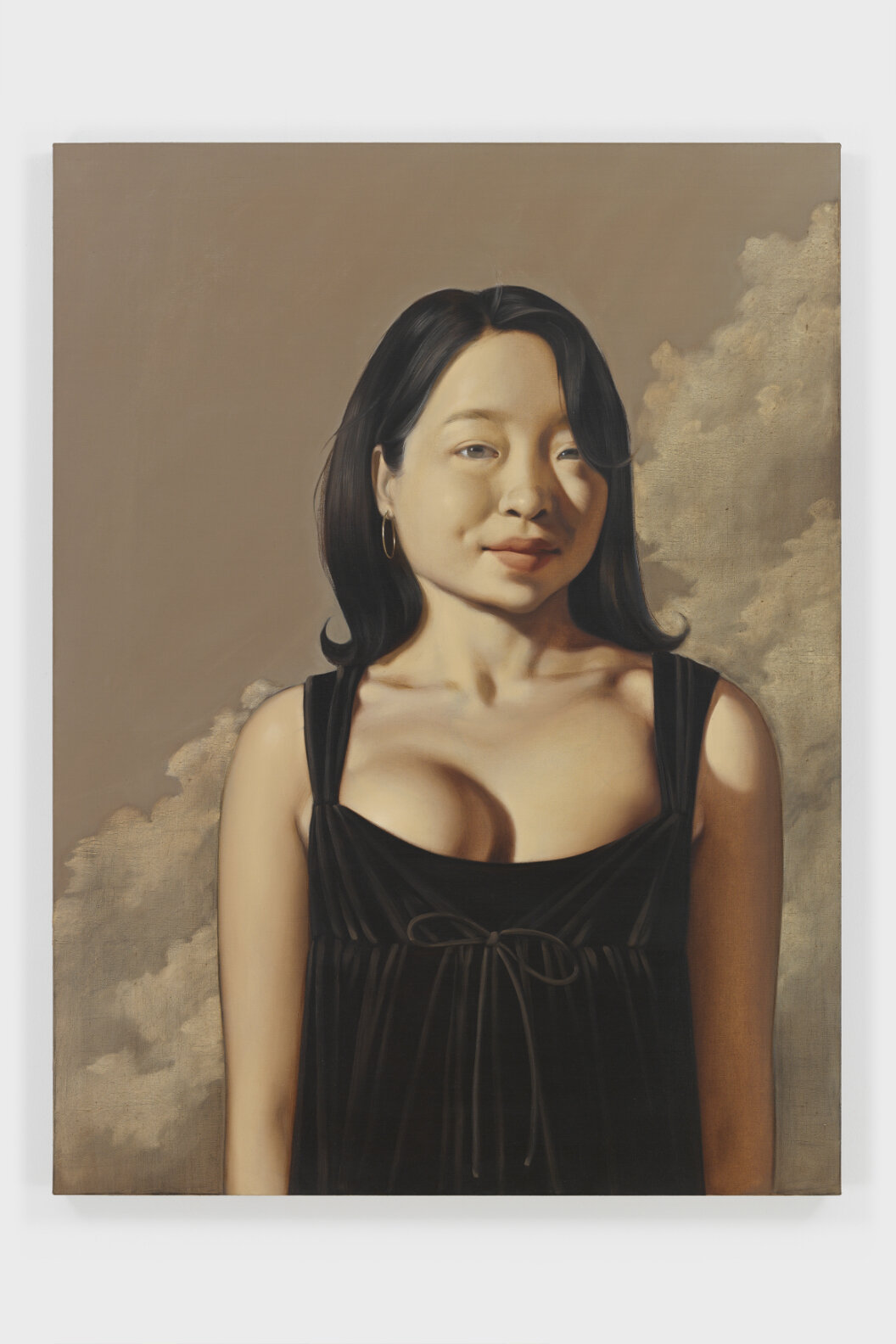

Jess Valice

The sculptor, 2024

Oil on canvas

182.9 x 152.4 cm

72 x 60 in

© Jess Valice - Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech

Photo : Matthew Kroening

WHELESS: Every artist has pieces that they want to keep and others that they’re happy to sell. What makes you feel like something just has to be yours to keep?

VALICE: There are some paintings that nobody can really appreciate as much as I know that I will or I can't necessarily trust that anybody would. There's a lot of people that just buy for investment and that's scary when I put so much of myself into these paintings. It breaks my heart for anyone to neglect the feeling that's in the work. Especially if it's one that's really powerful. I love all of them but there's some that are a little bit more powerful than the others. I've already experienced one of my paintings going to auction that I made after I experienced one of the darkest things i've ever experienced. It was a guy holding a bouquet of dead fish, which is just as beautiful as a flower, flowers have to die for you to have the bouquet. I understand that people have to put things in auction sometimes for whatever reason, that's not what I'm complaining about, but it's a trust thing when you love something so much, and I love creating poetry in that kind of way so much. So that being said, the ones that I feel like I don't trust anybody else with, sometimes I save them for myself.

AVERY: There's always one I feel a connection with in each series and I try to pay attention to that. Usually it's just a no-brainer like, this can't go anymore, it has to stay with me. But in the same vein, I've had ones where I'm like, oh that didn't go to the right place, or it just doesn't feel right and it's an intuition that you have when you're like, this work is important and shouldn't live with anybody but me. Sometimes I won't put a work in a show, or I’ll keep it because I still don't know what I'm supposed to learn from it or I just keep it because it confuses me. I have to keep it in my studio to figure out what it's trying to tell me. It's almost like a research piece. It's not necessarily that it's not done, I just don't know what I was getting at yet, so I should probably hold on to it to learn from it.

VALICE: I love that.

Mara is on view through April 20 @ Almine Rech 39 East 78th Street, 2nd Floor

New York