interview by Summer Bowie

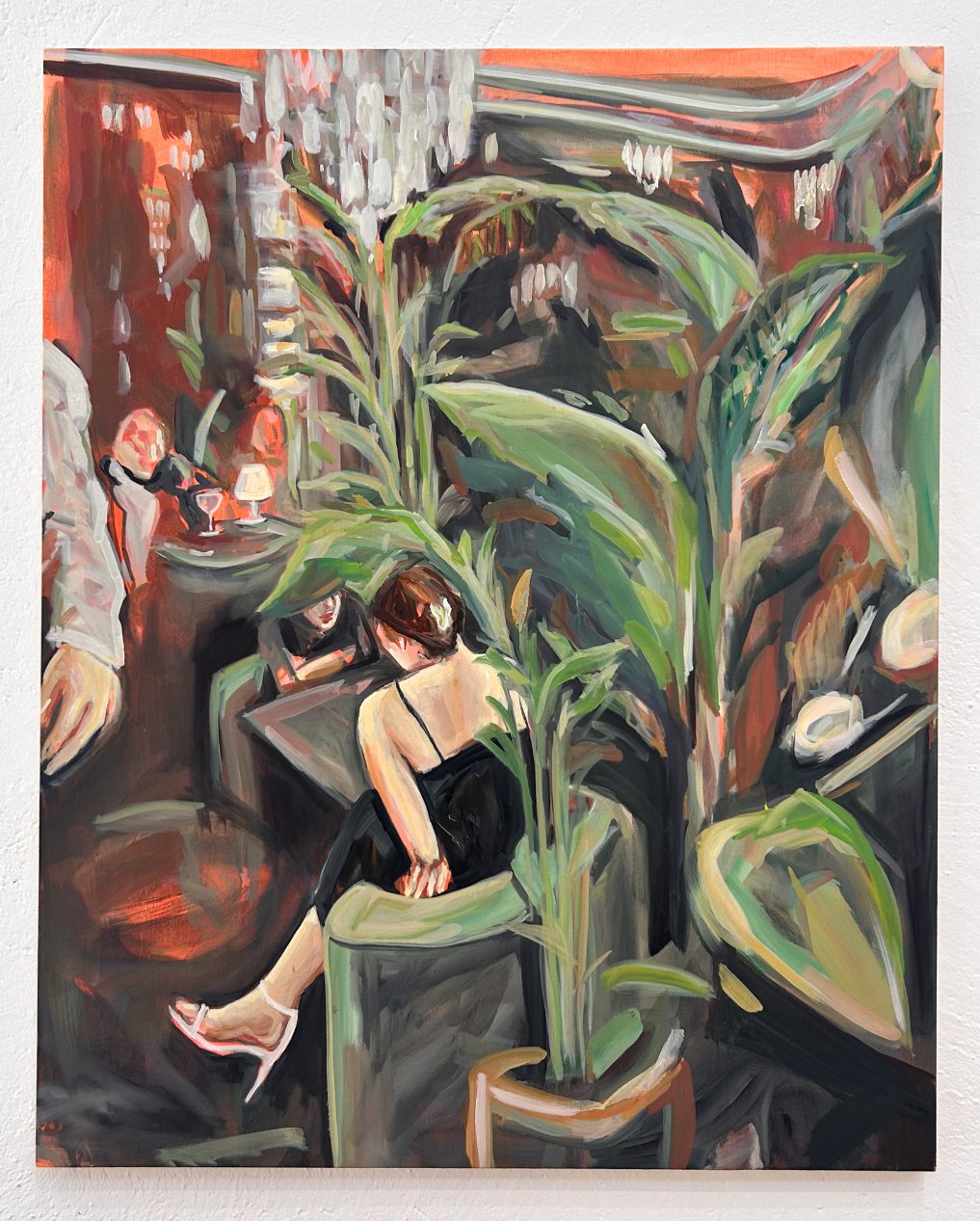

Avery Wheless is a Los Angeles-based painter who was born and raised in Petaluma, California. With her mother, a ballet instructor, and her father, an animator for LucasFilms, it’s no wonder she became a painter and video artist with a penchant for the theatrical. Her video works often depict movement artists performing choreography, and her painted portraits often depict everyday people engaging in the unconscious performativity of everyday life. Her current solo exhibition Stage, Presence on view at a private residence in Beverly Hills with BozoMag includes portrayals of the artist and her friends occupying glamorous spaces, caught in moments that subtly reveal the effort that comes with looking at ease. These acts are not celebrated or bemoaned. They just are. One friend reaches into the cocktail dress of another to lift and expose the fullness of her breast in anticipation of reuniting with an ex. Other figures unwittingly become subjects as they applaud an unseen performer or spy pensively on others while sipping martinis. The pageantry of hyper femininity is as vulnerable as it is manicured when you look at it from the right angle and Avery Wheless has a way of depicting it all simultaneously like an emotional lenticular on canvas.

SUMMER BOWIE: So, the title of your show is Stage, Presence and your work almost always relates to performance, but these works address it sort of indirectly. Can you talk about how that plays out in this body of work?

AVERY WHELESS: Well yeah, I like to explore performance in every way that it comes up in my life. My background is in dance and my mom was a ballet teacher, so performance was ingrained throughout my life. I started ballet when I was five and I always loved the make-believe worlds that you create in performance where you can be indulgent or take on another role. When I think of my body of work as a stage, it becomes a safe space for me to explore what it means to be a performer, whether it's in the more traditional sense of making art or just in my daily interactions. In this show, a lot of the images are taken from these in-between moments, whether it's friends getting ready or having intimate moments and conversations. I like capturing those moments when people may not realize they're already in this level of performance.

BOWIE: Right. We were talking a little bit about how your subjects are often captured in those moments when they're not actively performing, but they're preparing for the act.

WHELESS: Yeah. That comes up a lot. It's those moments when people don't realize they're getting ready for something or the stage isn't completely set. I find those moments more interesting and telling.

BOWIE: You often work from images that are taken in your everyday life, but then sometimes the paintings become amalgams of multiple images and memory. Can you talk a little bit about that process?

WHELESS: The images I take are sometimes these random, beautiful captures that I love of my friends when they're not fully aware that they're even being perceived by me. I like finding these softer, intimate moments with people. So I'm constantly hyper aware. It's also a way to process my environments and a feeling of being somewhat removed from a situation. Often when I'm surrounded by people, I feel like a bit of an outsider. So, I'll take those moments that I'm actually in physically and then there's other more emotional elements that come up that I'll adapt within the paintings to better explain where my body is in relation to what’s happening or what I'm thinking. Sometimes it's an object or it could be a motif that just comes out in the paintings naturally. It's a very subconscious kind of thing that just appears.

BOWIE: What was your early dance training like and what made you decide to paint instead?

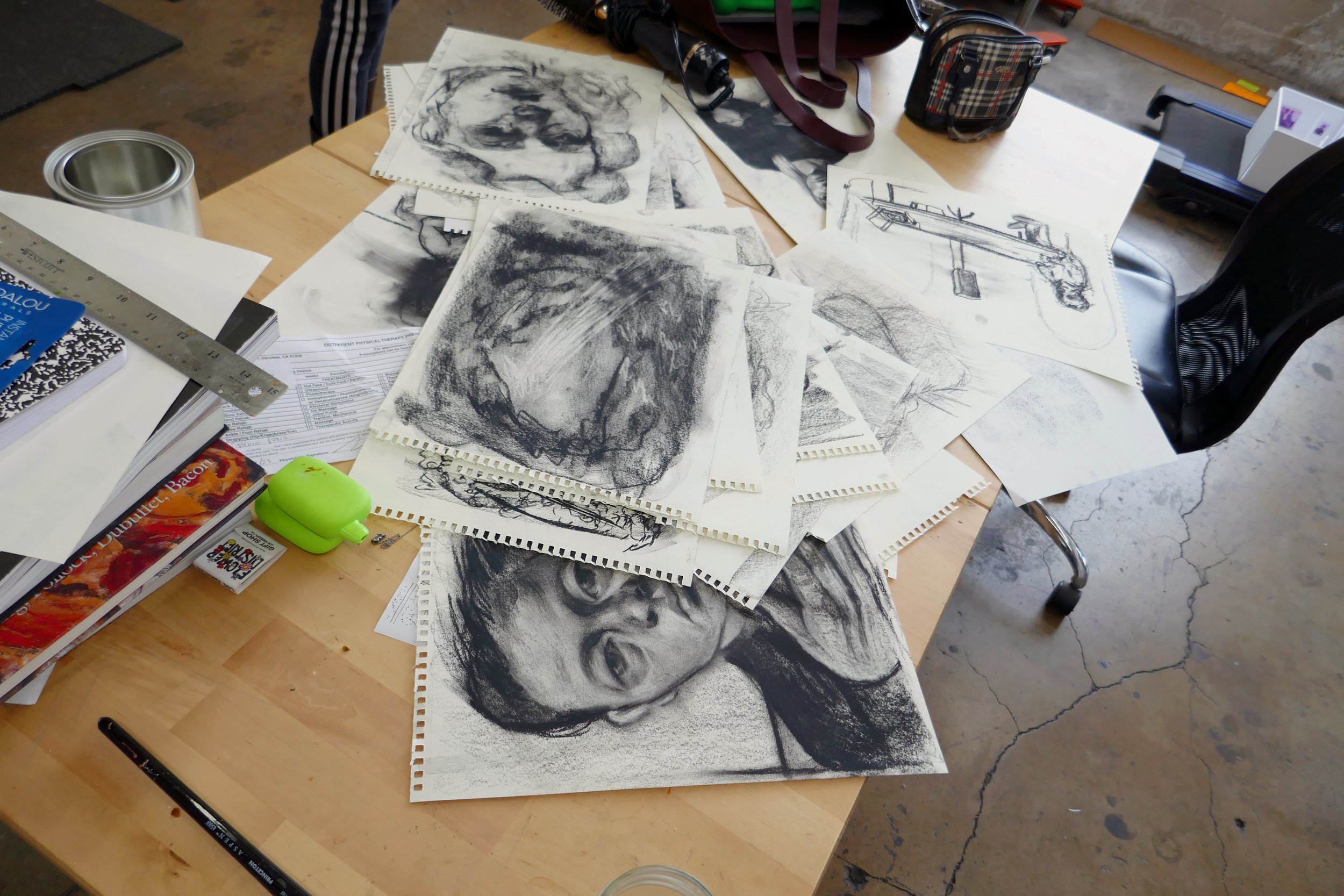

WHELESS: Dance was always something I craved doing. My mom and also her mom did dance and they were from the South, so they were involved in a lot of Junior Miss pageants. But my mom didn't let me do ballet until I was five and I loved it. When I was ten, I went through a tomboy phase and did more sports with my brothers, like baseball. I realized that the playing field was also a stage space, just with more of a masculine take. But it was a safe place to get involved very emotionally. After a year of that, I went to see The Nutcracker with my mom and cried because I wasn't in it. So, I went back and was training really intensely. For our summer program, classes would start at nine in the morning and we wouldn't end until six. And I would dance with Moscow Ballet when they were on tour. I loved the ability to be so focused on your own body and how it worked in relation to other people. But then, I got injured. I was dealing with some health stuff, and so I had to stop my training and that's when I really dove into expressing myself on canvas. I just transferred the intense training of ballet into my painting practice, and I think it always comes up for me while I'm painting—this level of movement and physicality when I'm painting bodies and performers.

BOWIE: It’s interesting that your mom and grandmother were involved in actual beauty pageants, but on a more symbolic level, there’s a lot of pageantry in your depicted scenes. They tend to be lavish dining and nightlife spaces, or sometimes your figures are lounging poolside.

WHELESS: Yeah. I think of my paintings as these stages that I set as a sort of director. I like capturing these environments that are a little bit heightened and theatrical. That's just part of what interests me visually and conceptually. There's a dramatic sense of dark and light, or sometimes they're pulled from more of a dreamlike state too.

BOWIE: You also have such a very signature style in your video work, and there's a continuity between the two disciplines, because they also often feature contortionists, pole dancers, and movement artists of many different forms. I'm curious where you find your subjects.

WHELESS: Well, video is always something that I've enjoyed. My dad's in film and animation. So, it was always just fun to capture movers and then explore it more in my paintings. I was doing that very early on. But a lot of my subjects are just friends or other collaborators that I love working with. The dancers that I worked with for my solo exhibition earlier last year were cami [árboles]—who I shot for a designer friend that I was working with—and she had all these dancers that were really excited about performing in front of paintings because pole dancing isn't usually experienced in a gallery space and we were like, let's just play with this. I like having things that are an extension of what I'm thinking and then letting someone else run with it. So, I was like, “This is the score. This is what I have in mind. Now I wanna see how that manifests in your body.” And then, about year later we did a whole other adaptation of it where I projected the video from the exhibition performance and they performed in front of that. So, the video becomes a moving extension of what I've been thinking about and the amazing friends and collaborators I've been lucky enough to have play with me.

BOWIE: I love that. It’s almost like an exquisite corpse, but it’s not, because it always has the potential of being reborn in a new iteration. Your subjects are pretty invariably feminine. Can you talk about that?

WHELESS: I think most of the subjects in my paintings are women just because I identify as a woman and they are all extensions of how I see myself. It's a processing of how I relate to the other women in my life, like my mom and my sister and my grandmother. Those relationships are really beautiful and complicated. I think that's why I keep coming back to them. Thinking back to my days as a dancer, the corps de ballet is all women, so I was always in this ensemble of female bodies. I mean, I have painted men, but my most intimate moments and the relationships that I find the most complicated and intriguing are usually with other women in my life. So, the paintings are an exploration of that and also how I view myself. I'm not always intentionally doing it, but there is a level of self-portraiture in them.

BOWIE: How you define the female gaze?

WHELESS: I like to think of my paintings as creating a stage where women can be viewed comfortably and are aware of being viewed or engaged in a way that's not coming from a place of judgment or aggression. It's a place where you can be fully exposed and also completely held at the same time.

BOWIE: Aside from human figures, the show also features two images of horses. I'm curious what inspired you to incorporate them in the show?

WHELESS: Yeah, I wasn't aware of them really until I noticed that they were central to a couple of the paintings. It started with a horse figurine at this restaurant called Delilah in Miami where I was having an intense conversation. There's a breath work exercise I like to do when I want to ground myself if I'm feeling sort of out of my body. I'll look at something in the room and really study it to bring myself back into a present state. I even did this as a kid when I would get reprimanded or if I was in trouble, I would look at a person's face and draw it on my lap with my finger. So, there was this horse figurine right next to me that I was studying while going through this heightened sense of awareness and it just stayed with me visually. And then, my friend sent me a photo of her with her hands around this other horse figurine and it was funny because it had the same color palette and her hands were lit really intensely by the flash. I was wrapping up works for the show and I had this one painting of a sleeping woman that I kind of liked, but I didn't love it. So, I painted over it, but I left the woman's face sort of visible. The horse and the hands are made with this really gestural, vigorous, frenzied mark making. It was almost violent because I was just processing a lot at the time. I was having these anxiety dreams and fever dreams, which happens when I'm stressed out. But yeah, with the horses, one came from a calming exercise, and the other came from a deep state of anxiety.

BOWIE: It's interesting because horses also have this duality of both wildness and bourgeois pageantry. I want to come back to self-portraiture because you talk about the female figures in your works being a form of self-portraiture, but then you also incorporate some direct self-portraiture. There's one in the piece that was adapted from a photo that a friend took of you. What was it about this particular image that made you want to paint it?

WHELESS: It was just a fun snapshot that my friend Bella [Gadsby] took randomly. But it was more about how the perspective of the foot makes it look almost like I'm stomping something out, but it's also playful. I'm relaxing at home with a friend, but my body is pushing forward in the frame and then also receding at the same time. In all of the paintings, there's a tightness, a looseness, and a kind of falling apart. I'll go into certain areas and make them as defined as I want and then the rest of it is this hazy, dreamlike state. But it's all held together by one anchoring point. In most shows, there's always one self-portrait that I end up doing subconsciously. And after it's done, I realize how it ties into the rest of the works.

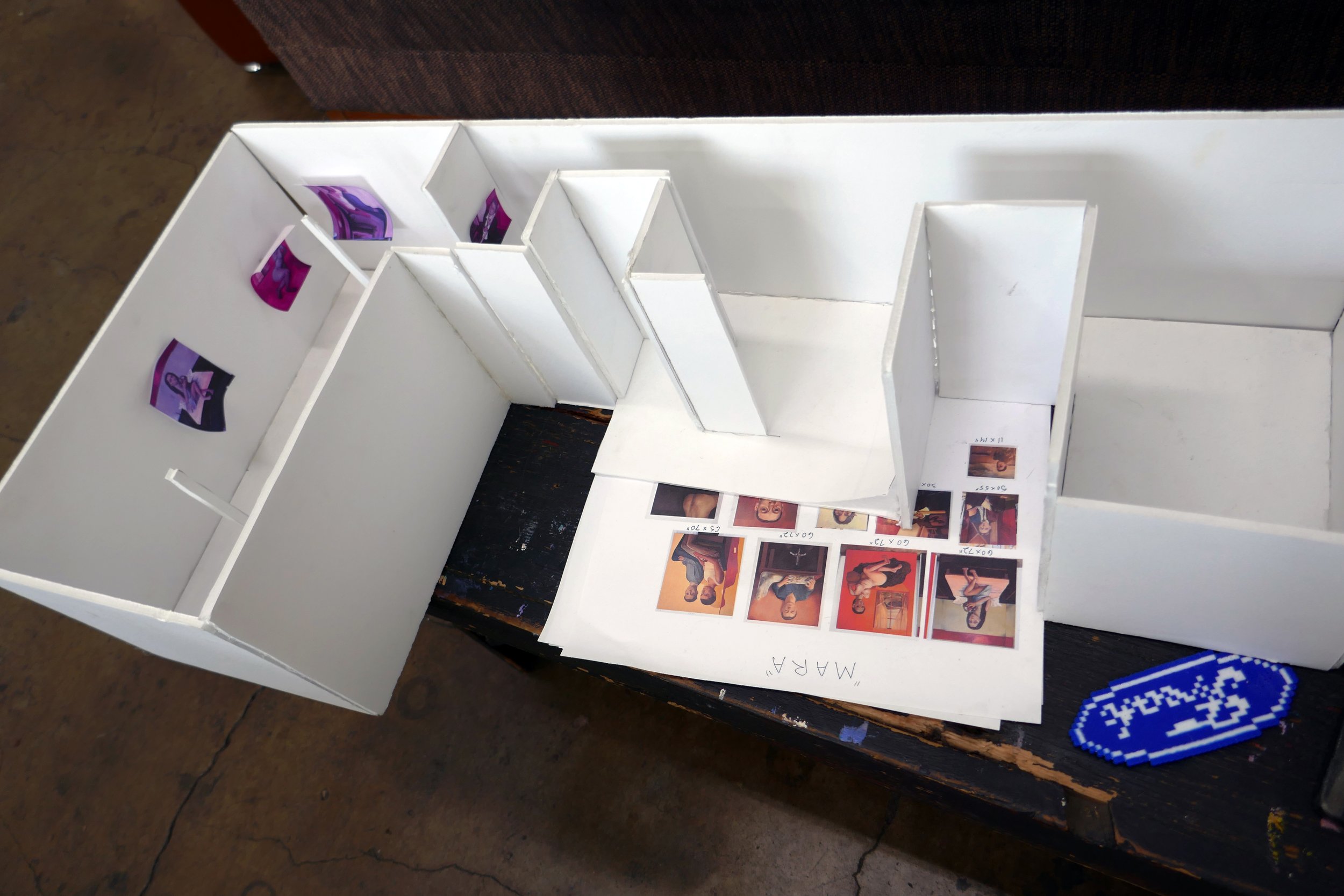

BOWIE: Can you tell us about anything that you're painting in the studio right now?

WHELESS: Well, I just got this new studio space, so I'm slowly starting to to dive into some works for NADA Miami, which I'll be doing with Bozo Mag. There's a circus theme I'm exploring, which is just another extension of the stage that I like because it’s really glamorous but also grungy at the same time. So, I've been thinking a lot about that.

Stage, Presence is on view through May 11 at a private residence in Beverly Hills. Contact BozoMag to book an appointment.