Clément Delépine

Director, Art Basel Paris

Photography by Inès Manai for Art Basel. Courtesy of Art Basel.

interview by Summer Bowie

For those of us who are insatiable art enthusiasts, arranging one’s art fair agenda is an art unto itself. It not only requires a close study of all that is on offer throughout the week and the precise timing of transport in between, but a realistic expectation of energetic reserves and proper meal planning. With that in mind, it’s difficult to imagine how one might ever go about organizing an annual program of this magnitude. Art Basel Paris Director Clément Delépine is a master architect of the art fair if there ever were one. Having cut his teeth as co-director of Paris Internationale starting in 2016, he has spent the past decade refining this rarefied practice that is a perplexing combination of curation, commerce, civic diplomacy, and social design. Aside from the 206 exhibitors at the Grand Palais, this year’s fair includes 67 events comprising performances, talks, satellite exhibitions, and guided tours in collaboration with 9 official institutional partners within the City of Light. As the drone of chatter about the declining global economy beats like a rolling snare drum, attracting a broad and diverse audience while striking the right balance of education, entertainment, and alimentation seems an impossible feat. And yet, Art Basel Paris is once again one of the most anticipated events of the art world calendar.

BOWIE: I want to start all the way at the beginning of your art career because you truly worked your way from the bottom. You started as an intern at the Swiss Institute, then moved up the ladder to eventually become the artistic director. And then, you became co-director of Paris Internationale before your current position as director of Art Basel Paris. Have you always had this blind ambition, or did it all happen more organically?

DELEPINE: Ever since I was a child I knew that I was destined for this. (laughs) No, I’ve been very lucky because I didn’t study art history—I was just responding to different opportunities. I moved to New York to escape a PhD program that I wasn’t disciplined enough to carry through. And then, I was offered an internship at the Swiss Institute. Eventually, the gallery manager was fired and I was asked to replace him, so my mom helped me with 5,000 euros to pay for a visa. From there, it all just accumulated. I met the right people, and back then in New York, you could invent yourself completely, and chances were given.

BOWIE: Was it the opportunity to direct Paris Internationale that brought you back to Paris?

DELEPINE: Well, not really. The real reason I moved back to Paris was because my wife and I wanted to have a child. I was born and raised in Paris, and I spent a lot of time in Zurich, but nonetheless, Paris was my hometown. When I was growing up it was a very hostile city, but since then it changed a lot. I came back to Paris from New York in 2016. And just by chance, I met a couple of gallerist friends from Galerie Gregor Staiger in Zurich. They had founded Paris Internationale the year before with Silvia Ammon who needed an accomplice, so to speak, and they offered me the job as co-director of the fair. At that point, I had been a curator of a non-profit and I had been an artistic director of a commercial gallery, but I was slightly afraid that working for a fair would be confusing—that it would give the impression that I didn’t know what I wanted to do, which in fact was the case. However, I decided to embrace the opportunity and it was very satisfying. So, I ended up doing that for five years, and ever since, the city started to feel very open and international and cosmopolitan again, so it felt like the right context.

Installation view of Alex Da Corte’s performance Kermit The Frog, Even, Fridericianum, Kassel, 2024.

Courtesy of the artist and Fridericianum, Kassel

The project will take place at Place Vendôme in Paris

BOWIE: The timing of that is very interesting too because it marks the beginning of the first Trump administration and also of Brexit. You got out of this mess that I’m in at just the right time. (laughs) But also since Brexit, there’s been this major surge in international galleries opening outposts in Paris. How would you characterize the current art scene there now?

DELEPINE: It’s a very vibrant dynamic, I have to say. Brexit was really the entry point for the European Union asserting its own art economy. Italy just passed a lower VAT rate [Italy’s value added tax was at 22% before Brexit]. It just went down to 5.5%. It has been 5% in France for some time now, so it was very helpful for the French market. Acquisitions were always the most important market within the EU and for the art market globally, so it’s very active. There is a much bigger community of galleries, and an unparalleled institutional landscape of public museums and private foundations. When I was in New York, the Paris scene was perceived as very dusty, but since 2016, there’s been a lot of new dynamics. These things work in cycles, of course, but back then, London was the economic center and the epicenter was Berlin. Now it seems like Paris combines those things, which is a good alignment of the stars for us. The gallery scene in Paris has many heavy hitters now like David Zwirner and Hauser & Wirth, who opened at great scale, and they wouldn’t do that if they didn’t trust that the French model could sustain it. So, It’s good energy at the moment.

BOWIE: Has the increase in art galleries led to a rise in artists working in Paris?

DELEPINE: I would say yes, but it’s a perfectly subjective question. What I can say is that my Instagram feed is full of young artists in search of sublets or apartments, and it really gives me Berlin vibes from the mid aughts, which is quite encouraging. Real estate is expensive, though. Paris is not extremely affordable, but it seems cheaper than other European capitals—London and Zurich, for instance. You can still find studio apartments, and it’s a very small, dense city. Plus, it’s very central. From here you can reach pretty much anywhere in the world.

BOWIE: Can you describe one recent artwork that made a profound impression on you?

DELEPINE: I just came back from Uzbekistan, where I went to attend the Bukhara Biennial that Diana Campbell curated, and her curatorial premise was to bring artists and artisans from Uzbekistan who emphasize the healing and transformational power of art. I attended a performance called the Bukhara Peace Agency Sozandas conceived by Anna Lublina, who’s a theater director. It was storytelling coupled with traditional Uzbek dance and song. This was in the context of an art biennial, which is meant to bring the work of these artists and artisans into the global art dialogue, but it was equally made for an audience of locals. There were many families and kids running everywhere next to a 13th century mosque. It was profoundly beautiful.

BOWIE: I want to turn now to Art Basel Paris to ask you about some of the successes of the inaugural edition that visitors can expect again and what will be different?

Art Basel Paris

Courtesy of Art Basel

DELEPINE: The inaugural edition at the Grand Palais was a success in the sense that it was one of the most anticipated events on the art fair calendar last year. We were also the first event to follow the Olympics, so the Grand Palais had been closed for five years. This meant that we had to plan for it while essentially blindfolded, because the renovation got delayed and we couldn’t access the building—first due to the Olympics, and then because of Chanel. So, it was a real leap of faith. The day before the opening while standing from the balcony to see what came together with the team was a very moving moment, and all of that is coming back.

There are slight changes on the floor plan because we mapped out the directory more precisely. Some galleries have moved, we’ve reinforced the signage and the experience in terms of food and beverage, the restaurant au Grand Palais is open, so there are more quality options to choose from, and we’ve created a new reception to welcome guests in a more fluid and breathable fashion. We’ve also reinforced the partner program, which is the institutional component of the fair. That takes place across nine sites throughout the city, and we’ve turned Avenue Winston Churchill, which separates the Grand Palais from the Petit Palais into a pedestrian space. Then, there is the conversations program, which will feature a full day of conversations curated by Edward Enninful, among many others. It's extremely abundant and, I hope, generous.

BOWIE: Nearly a third of this year’s exhibitors are either French or operate within the country. Why was it so important to maintain such a high ratio of French representation?

DELEPINE: Because it’s important to be anchored within the French scene. In terms of narrative, it needs to say something different than Art Basel or Art Basel Miami or Hong Kong or Doha, and it needs to serve a different purpose. When you cater to the same audience five times a year, you have to offer something different. Besides the Grand Palais, which is highly recognizable, I want the visitors to look at the floor plan and immediately know that they’re not in Basel. On the one hand, it’s a commitment to the city, and on the other hand, it’s a promise made to our visitors that it’s worth coming to Paris.

BOWIE: The art fair fatigue is a very real thing, so there’s a lot to be said for a site-specific offering. The fair also brings together galleries from forty-one different countries. Last year, we saw work from Lambda Lambda Lambda, which is the only contemporary art gallery from Kosovo with international recognition. Can you talk about your approach to diversity and balance when curating the exhibitors list?

DELEPINE: Absolutely. The fair aims to celebrate excellence within each segment of the market. It’s important to identify the leading voices within each community and to serve wide and emerging audiences. I want the visitors of Art Basel Paris to be confronted with galleries that frame the conversations, whether they take place at the very forefront of the avant-garde or in the most well-known art galleries. The last Venice Biennale theme was Foreigners Everywhere, and if the fair had a theme I would want it to be titled Masterpieces Everywhere. Whether that be a masterpiece from an emerging artist or Pablo Picasso, we have to look beyond any specific geography or market. Earlier this year, I visited the Islamic Arts Biennial in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, which was all about challenging the notion that the West is the art world’s center of gravity. The canon should not be exempt from Western influence, but the rest of the world should not be belittled by it either. Ultimately, you serve the French scene when you position it on the same foothold as the excellency of the international scene; you create context.

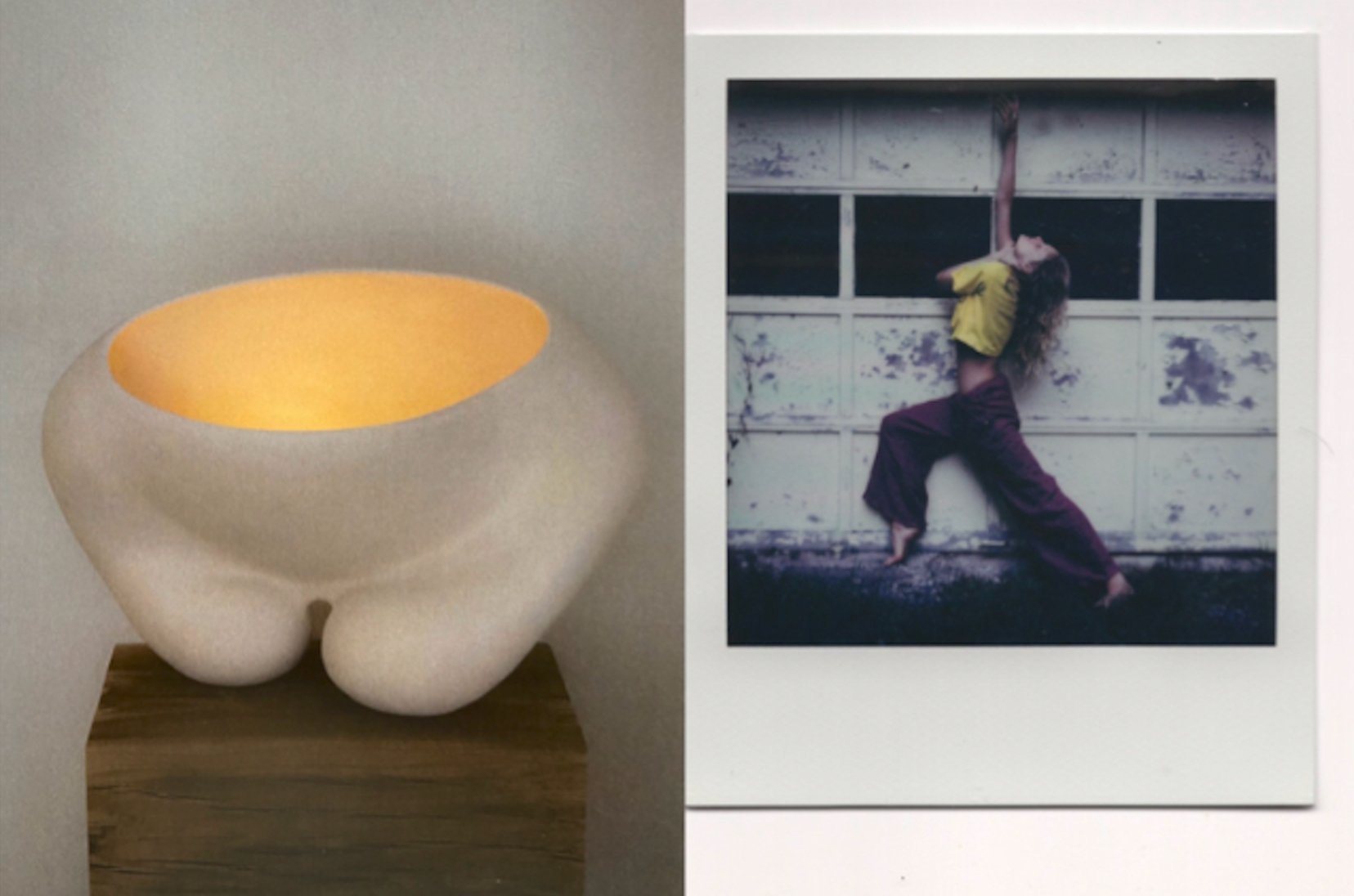

BOWIE: You’ve always championed multidisciplinary dialogues as well. This fair in particular, embraces the blurring of lines between art and fashion. What do these disciplines gain from one another?

DELEPINE: These disciplines have often flirted with one another without always holding hands in public. But clearly, the inter-penetration, so to speak, has been made more obvious. I’m thinking of several fashion designers who are important art collectors, like Hedi Slimane, Jonathan Anderson, Raf Simons, Rick Owens, Pieter Mulier, Jacqemus. All of these designers collect art, their collections are inspired by art, and they collaborate actively with artists. Of course, Miu Miu is a partner of the public program, and Mrs. Prada has been known for championing artists and commissioning films by woman filmmakers.

Then, of course, there’s people like Helmut Lang or Martin Margiela, who transitioned from being fashion designers to visual artists and weren’t initially taken seriously as visual, conceptual artists. I never understood why a creative genius should have to be segmented, but I think those times are over, and these creative fields are much more porous. This is something we have to be attuned to because the people buying art also buy fashion, and are interested in things like sneakers or Labubus and other cultural signifiers. With an event of our caliber, we always have to question how we can continue to make the fair desirable for a younger generation of collectors.

BOWIE: Those Helmut Lang mattress sculptures are just incredible. And they’re actually a very logical continuation of his practice, considering that the mattress is a textile, and they’re often punctured, or perhaps impaled, by metal poles. So, it wasn’t a huge leap from threading a needle through fabric.

DELEPINE: I agree. If you consider Eckhaus Latta, for instance, they have been shown at MoMA PS1 and the Whitney Museum in what are considered very art-sanctioned exhibitions, so it means something.

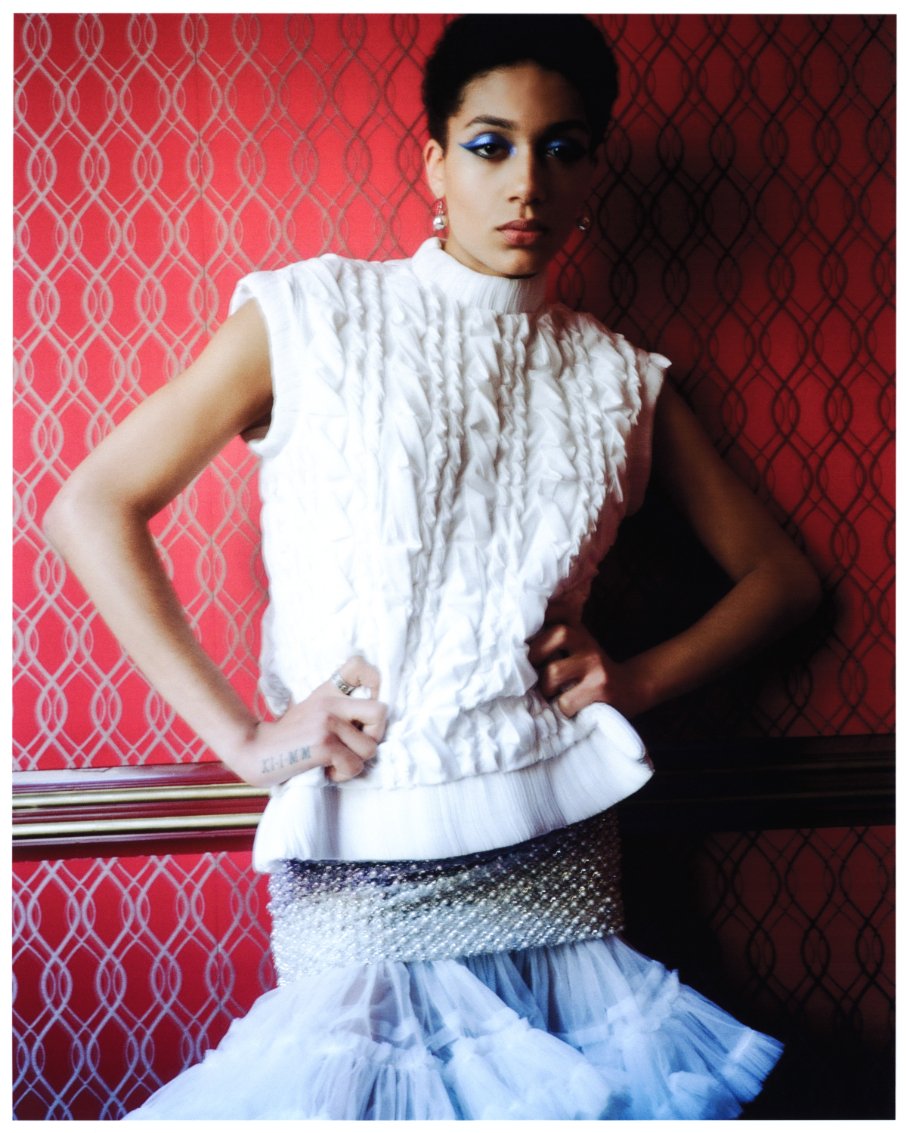

BOWIE: And this will be the second year that the fair is officially partnering with Miu Miu. How did that come about and why not a French brand?

DELEPINE: I’m quite stacked, you know, with French brands. No, I’m joking. You know, Vuitton is an important partner inside the Grand Palais, so is Guerlain, but it’s not necessarily about France in this case. The commitment of Mrs. Prada and Miu Miu is unquestionable. They are, in my opinion equally credible interlocutors in fashion and in the visual arts. We’ve organized something at Palais d'Iéna, which is the location that they’ve used for their Paris runway show for a long time, and with fashion week taking place just three weeks before, it felt like a natural dialogue because it makes Art Basel visible to the Miu Miu audience, many of whom probably would not have set foot in the Grand Palais had it not been for this collaboration. It’s also an acknowledgement of the work that Miu Miu and Mrs. Prada are doing for the arts, so it’s a match made in heaven for us.

Art Basel Paris - Public Program

Courtesy of Art Basel

BOWIE: When discussing markets within just about any industry lately, the word uncertainty rings like a mantra. In the US, we’re seeing many emerging and mid-size galleries closing their doors. How are you feeling about the global art market these days?

DELEPINE: I mean, the numbers are low for everyone, and the art market, just like any asset, is not immune to the situation. The uncertainty is being fueled by the tariffs and the wars raging on, which leads to the rising cost of transporting premium goods. Certainly, things have been much better, but things have been way worse as well. It’s not the nineties, it’s not 2008, and it’s different from 2014. It’s a new cycle and a definitive generational shift. Some big names, like Tim Blum are sunsetting their galleries, and some are questioning how to reconfigure. There are also very young, energetic, and ambitious galleries that are seizing opportunities to establish themselves as new players. One could say the market is in crisis, but one has to remember that the etymology of the word ‘crisis’ is decision. So, now is the time to make important decisions. We’re definitely moving past the COVID phase and the fruits that it bore, and some of the galleries didn’t make investments following COVID, which proved unwise. It seems to me like the market is now finding a new temple. So, I’m not pessimistic, which is rare considering that I’m French. (laughs) This should be acknowledged. When I was in Bukhara, when I was in Saudi Arabia, wherever I travel, people are so excited about the Paris show. The feedback from the VIP reps is really important, and all the art advisors tell me that their biggest clients are coming and that everyone wants to be there. As a fair, it’s important that we craft a platform for commerce and transaction, but the galleries are equally, if not more interested in the new audiences we can bring to the event and in that respect, I think we are prepared to fulfill their expectations.

BOWIE: I was speaking to a young art advisor who used to intern for me, and she was saying that the one thing she’s seeing is that there are new opportunities for young collectors who normally wouldn’t have access to certain artists or works. So, this transitional period is providing new opportunities for people who are just starting their collections.

DELEPINE: It’s true. Sometimes the polar dynamics shift. Sometimes, a gallery is sufficiently empowered to prioritize its collectors because they have thirty people on the waitlist, so they can tell a collector to buy two and give one to a museum. These are tactics that have been well documented. And sometimes, the collectors take power back. It’s an important balance. Some collectors feel like they’ve been barred from accessing a certain caliber of works, but they shouldn’t be resentful. That’s the way market goes—offer and demand. Au contraire, they should take the opportunity to get their hands on works that were inaccessible to them only a few months ago.

BOWIE: I’m curious about the Premise sector, which is less about the commercial core of the fair and more about unusual, unexpected juxtapositions, or neglected histories. What can we expect to see there?

DELEPINE: The Premise sector is all about storytelling. In French we have a term called passeur, which doesn’t have an English equivalent, but it has to do with the dissemination of knowledge. So, this sector is configured in a way that encourages you to slow down. The booths are smaller and you can really focus on what you are looking at. You can expect to see the works of Hector Hyppolite, for instance. He’s a Haitian painter who has been overlooked and rediscovered as one of the very first heroes of Black portraiture. The Gallery of Everything is going to present a solo of his works with all the paintings that once belonged to André Breton and some of the works that were shown at the Centre Pompidou in the context of corps noir earlier this year. On the other end of the sector, we have a Robert Barry presentation staged by Martine Aboucaya that includes some of his rare immaterial works from 1969 and refers to his performance in the ’70s when he buried radioactive waste in Central Park. I find this quite interesting in an age when we’ve long felt like the nuclear threat is far behind us, and yet, it’s sadly relevant. Pauline Pavec will show the work of Marie Bracquemond, an impressionist painter whose career was interrupted because her husband who was also a painter forbade her from painting because he felt threatened by her success.

BOWIE: What is your best advice for navigating the Grand Palais so that you can see it all and pace yourself?

DELEPINE: Come at the very first minute, stay until the security kicks you out, hydrate yourself and not only with champagne. The fair is a very nice scale. It’s 206 exhibitors, but it’s 195 booths. You can do the booths without rushing or leaving the fair with a headache. Enjoy the setting, pause every now and then to remember where you are, look up at the sky through the glass ceiling. It’s a great experience. Last year on opening day, it was such a bright blue sky, beautiful sun, the energy was buzzing, you know, it was wonderful. A fair can be intimidating, but one should never feel embarrassed to ask questions. Because ultimately, even though gallerists can be tired after eight hours standing in high heels having had little to eat, if you show interest in the work, there’s nothing more exciting for an art dealer than to celebrate the work of the artist that they represent.

BOWIE: My last question for you has to do with your current career transition. Your new appointment at Lafayette Anticipations will be your first time directing a museum. How are you preparing for yet another new role in the art world?

DELEPINE: Well, I’ve dreamed for a long time of running an institution and everything is moving so fast, I really haven’t had much time to prepare. (laughs) I want to be respectful of the history, the legacy, and to bring my vision and my new ideas. But honestly, it’s still a little too early to prepare. I mean, I still have so much to do with the fair that this is a question for October 31st. Right now, I’m fully dedicated and committed to the show at Grand Palais.

Art Basel Paris takes place October 22-26 @ Grand Palais Avenue Winston Churchill 75008, Paris

Ugo Rondinone

The project will take place at Parvis de l’Institut de France in Paris