interview by Chimera Mohammadi

The iconography of fertility holds a timeless power over us. Our paleolithic Venuses defined this obsession, encapsulating fertility as a powerful force of creation, rooted in the divine feminine while remaining paradoxically universal. Intersex artist Katharina Kaminski expands upon this understanding in her new show, Womb, which embraces our individual potentials for transformation and innovation while interrogating our gendered ideas about fertility. As we find ourselves in the throes of a gender revolution, Kaminski reckons with the intersection of gender and creation in her abstractions of the womb: soft vessels fill the Sainte Anne Gallery, distilling the Venus to its core sense of creation and transformation. In recognition of National Intersex Awareness Day, Katharina comes together with intersex model and activist Hanne Gaby Odiele to discuss creating while Queer, finding community, and claiming ownership of the self in the wake of bodily alienation.

MOHAMMADI: How did you two learn about each other? What influence has your mutual discovery had upon each of you?

Katharina Kaminski: I met Hanne at a party in New York. Back then, I already knew that I didn't have a womb and ovaries because I had no period, had gone through surgery at fourteen years old, and had been under hormone replacement therapy since then. But I wasn't informed at all about my ‘condition’ and I thought something was wrong with me—that I was the only one. I felt victimized because doctors encouraged me to hide the truth about my body and didn't feel there was someone who understood enough to speak about it. I had been following Hanne on Instagram before personally meeting her. I read about her activism on intersexuality and I started suspecting, maybe I am intersex too! I started studying about it and all I was reading matched with me. So, I introduced myself to Hanne and said, “I think I might be intersex too!” A couple of weeks later, I went to do a blood test and solved years of uncertainty when I received the results that I have XY chromosomes. Thanks to Hanne, not only did I learn what it means to be intersex, and that there is a beautiful community of outspoken intersex people in the world, but she also inspired me to be proud of it. She gave me the information to understand and the inspiration to speak.

Hanne Gaby Odiele: We met randomly at that party years ago. I think Katharina already messaged me before on social media right after my disclosure. After that, we kept in touch, and we met again when Katharina was spending some time in New York. We not only bonded over our intersex journey, but she also shared with me her passion for art and her newfound love for her sculptures.

MOHAMMADI: Do you consider yourselves activists?

KAMINSKI: I don't consider myself exactly an activist, but as an artist, there is a strong connection between my sculptures, the body and gender, which are issues that have been focal points in my life. If I have the chance to speak to many (like now), and there is someone else who can benefit from that, as I benefitted from Hanne being open about it, then I feel I have the responsibility to do so.

ODIELE: I’ve done a lot of activism in the past, since it was important to me to tell my story and bring to light the irreversible, unnecessary, non-consensual surgeries that intersex children can be subjected to. I also wanted to point out that intersex bodies are beautiful and perfect just the way they are. Since my disclosure I’ve seen a lot of new intersex activists emerge. I’ve been focusing less on activism myself. For me, it’s also important that being intersex is just a small part of who I am: it doesn’t have to be a big deal.

MOHAMMADI: Kate Bornstein opens their radical 1994 book Gender Outlaw with the phrase “My identity becomes my body, which becomes my fashion...” Has modeling informed your relationships with gender presentation, identity, and the way that many trans/genderqueer people’s feelings about their bodies range from mournful to celebratory? Odiele especially has spoken at length on their anger toward the medical policing of non-binary bodies. Has this complex emotional spectrum in relation to the body been a theme in your respective creative work?

KAMINSKI: Definitely! My sculptures have these alternative corporealities and I started doing that totally unintentionally. I feel my work is supercharged with that deep complex emotional spectrum. That's why I actually decided to present myself as intersex in connection to my work. Even though it doesn't define me, it is really present in who I am and in my art.

MOHAMMADI: In Man and His Symbols [1968], Jung describes the necessity of “the symbolic mood of death from which may spring the symbolic mood of rebirth.” Did you experience the discovery of your intersex identities as a death and subsequent (re)birth? How did claiming your identities place the act of creation into your own hands?

KAMINSKI: More than discovering my intersex identity, what felt like a rebirth for me was allowing myself to feel fertile and whole.

MOHAMMADI: Does Womb anthropomorphize the womb or render it inanimate? Or might it do both?

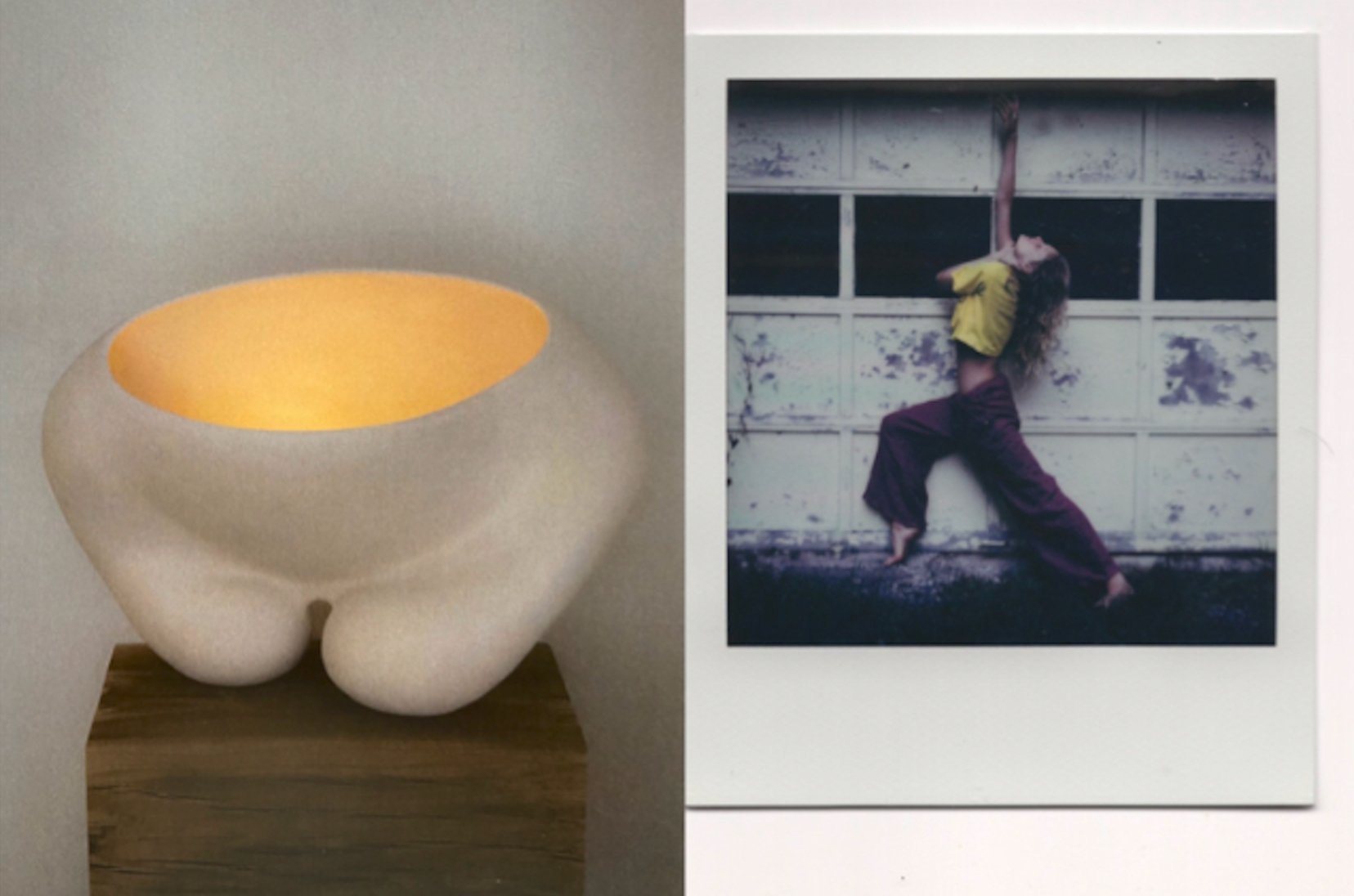

KAMINSKI: I am more interested in the ‘womb’ as this energetic center where life and creativity are born, rather than its physicality. It's kind of ironic, because as a sculptor, you normally want to make your subject material, give it a form. In this case, I think because I’ve been going through the process of disconnecting from the feeling of lacking my physical womb, and connecting with my fertility beyond the matter of an actual organ, I wanted to explore deeper understandings of the embodiment of a womb. The exhibition at Sainte Anne Gallery has two floors: on the first floor I am presenting my sculptures for the first time in new mediums: marble and bronze. It’s a more brutalist side of my work and the biggest scale in which I have ever worked. On the second floor, after you walk up the stairs, you enter the Womb: a Light and Darkness installation with ten Light Sculpture Beings in different types of clay. It feels like being inside a sanctuary, or in the ‘womb’ of your mother.

Katharina Kaminski

The Womb (2023)

Clay + fire installation

200 x 180 x 150 cm

MOHAMMADI: Womb forges a non-biological definition for fertility. How does this understanding of fertility feed your creative instincts?

KAMINSKI: Fertility is not only about creating human life, it is about creating. The title of my exhibition is a metaphor for the inner plot twist I allowed myself. From feeling absent and infertile to a sense of abundance and fecundity.

MOHAMMADI: I was very interested in the term “surrealist body language” in Womb’s press release. Can you elaborate on what that means to you?

KAMINSKI: I'm very interested in the mysticism of creating. Through my creative process, I seek to connect with the unconscious. Like a womb, I offer myself as a portal from the spiritual to the physical and I allow the sculptures to become alive. I think the concept of ‘surrealist automatism’ resonates a lot with my way of creating. I find it unnatural to start a sculpture from a thought in the mind, wanting to predict and control a result. I find it uncomfortable and boring. The mind is limited. I'm more interested in going beyond that, where emotions are raw and free and the mind can't comprehend. So for me, creating is a ritual, or a dance between me and the clay that allows the sculptures to become alive in their own unique enigmatic corporealities.

MOHAMMADI: What media exploring non-binary identity do you find particularly meaningful?

ODIELE: I love the art of drag and performance. I think it has helped me accept many contradictions and perceptions I had about gender. Like a wise queen likes to say, “We’re all born naked and the rest is drag.”

Womb is on view through December 20th at Sainte Anne Gallery, 44 rue Saint Anne, 75002, Paris.