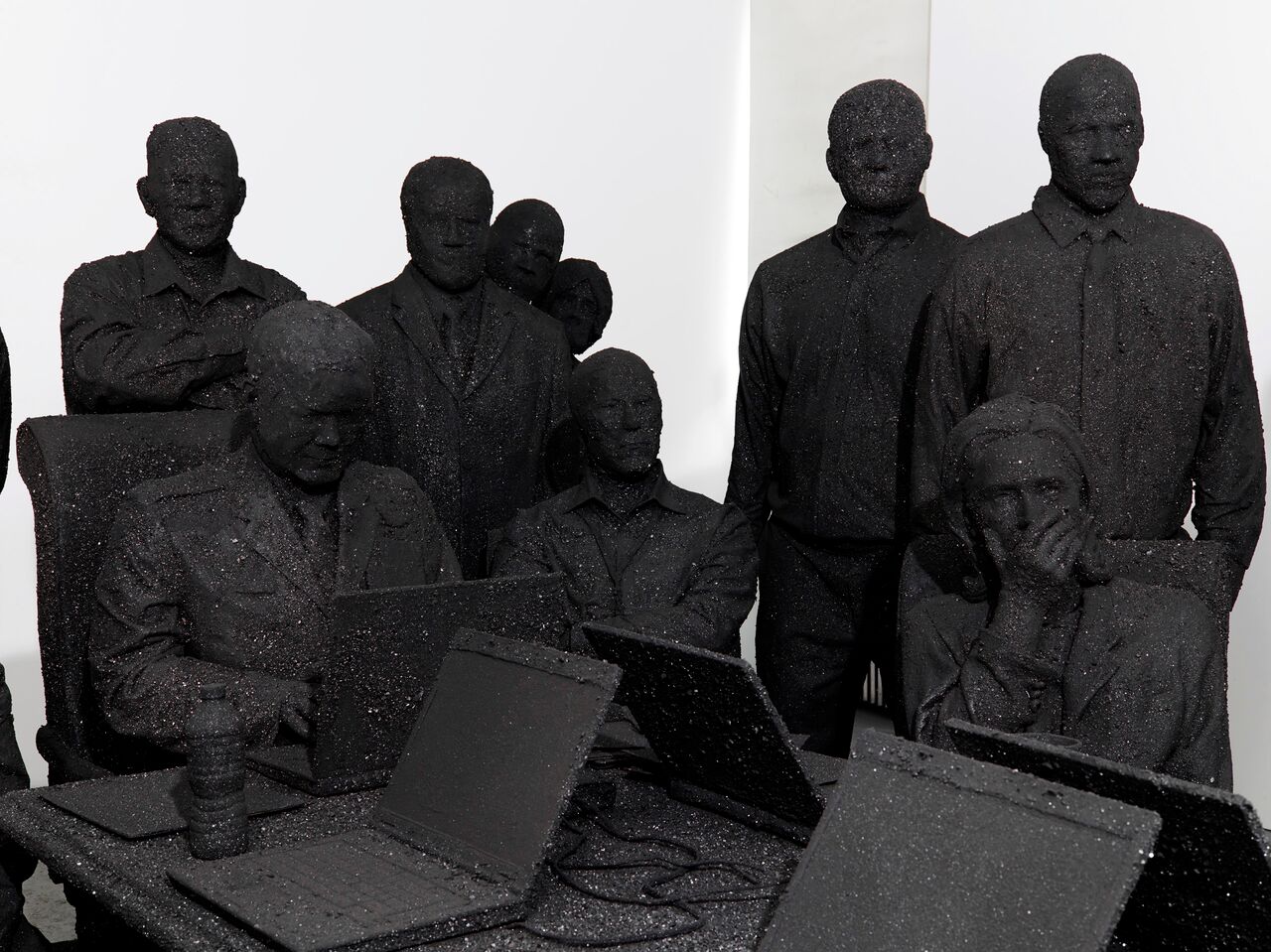

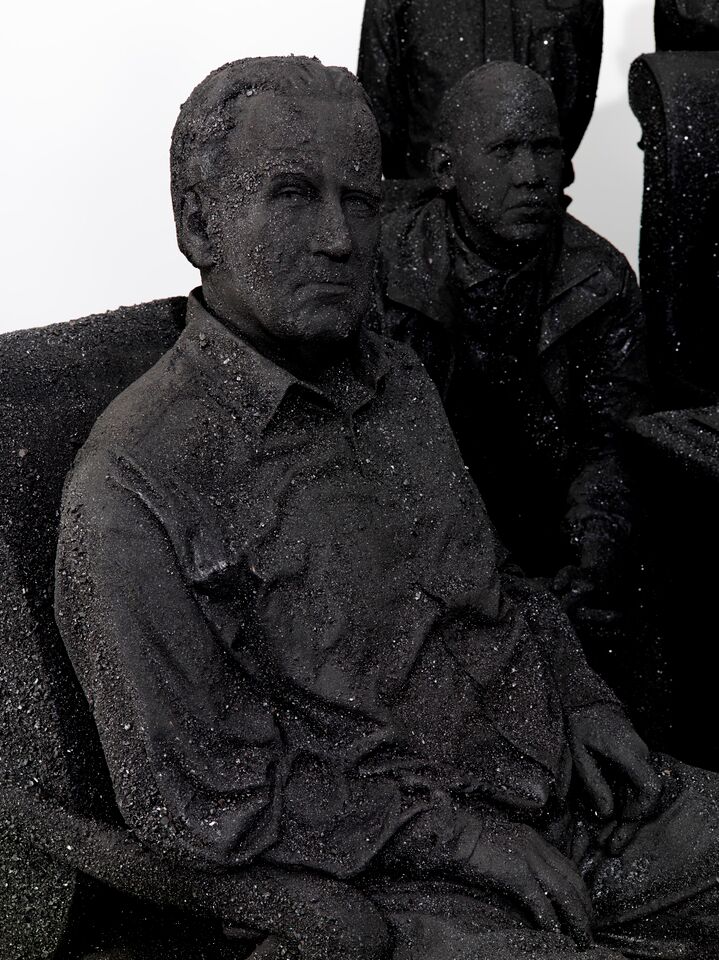

Will Ryman is a brilliant puppeteer and manipulator of materials to expose innate contradictions in history, commerce and power. It started with a gilded reinterpretation of Abraham Lincoln’s childhood cabin and took even more shape when he crafted a true-to-size 1958 Cadillac and coated the entire thing in Bounty paper towels. It’s simple distillation and refinery, and Ryman is the centrifuge forcing the base materials to the surface – the resultant work connotes a singular layer of blatant truth. His upcoming exhibition at Paul Kasmin gallery, Two Rooms, is an even more advanced exploration of this distillation and stripping down. There are two installations. One is a life-size sculpture – entitled The Situation Room – that is based on the iconic photograph of the Obama administration watching in real time the Navy SEAL raid on Osama Bin Laden in Pakistan in 201l. The twist: the entire sculpture is crafted out of crushed black coal. In a contemplation of “war, power, propaganda, industrialization, and political theater,” the sculpture seems to also bring to light our ulterior motivations in the Middle East, the plundering of natural resources, and the blood spilt to acquire such dubious ends. Another installation, entitled Classroom, features 12 students at their desk chairs – each of the twelve sculptures is made out of a different material: cadmium, titanium, salt, iron, oil, chrome, copper, wood, and gold – are we all reduced to simple commodification?

Will Ryman wasn’t always an artist. He wanted to become a playwright. Perhaps it was a rebellion from his painter parents – his father is famed minimalist painter, Robert Ryman. After twelve years, though, Ryman realized that the characters in his play couldn’t come to life like his future sculptures and installations could. Art seemed the perfect medium to explore the themes he was interested in.

We got a chance to catch up with Ryman over the phone from New York. We had an enlightening chat about materials, crude oil, his sculptural installations and we ask whether he is hopeful or fearful about the future ahead.

Oliver Kupper: Growing up with parents who were artists, did you always know you wanted to become an artist?

Will Ryman: No, I didn’t. Initially, after high school, I wanted to be a writer. I tried to launch a career in writing. I wrote plays and screenplays. Slowly, I started to sculpt the characters in my plays. That’s how I started to become involved in installations and sculptures.

OK: You were a playwright for twelve years. That’s a long stretch of a career. What themes were you working with as a playwright? Were you more successful as an artist in interpreting those themes?

WR: As a playwright, I was interested in writers like Beckett and Ionesco. I was interested in plays that had to do with approaching our culture from a cathartic and absurd place. I’ve always been interested in how things got to be how they are in our culture—whether it’s internal psychology or external social relations. That’s what I wanted my plays to be about. They were very abstract. It was very difficult for me to get anything produced. A lot of people didn’t understand them. They weren’t traditional in a structural or commercial way. At the time, people were looking for the Reservoir Dogs style. They were looking for the next Seinfeld. My work was nothing like that. I was frustrated; I started questioning myself a lot. I was also a very young man, so I had a lot of uncertainty about everything. I became blocked. What I was interested in, what was in my true nature was not working out. I tried to make my characters 3-dimensional to see what that would do. I started to work with materials, and I became interested in the same subjects that I’m interested in now.

OK: What are those subjects, specifically?

WR: Like I said, I’m really interested in how the world got to be the way it is today. That’s a huge topic. Within that, I’m interested in external issues like how the system—mass production, capitalism, technology, social issues—how that evolved to the way it is today. My work is about retracing that and exploring what’s underneath all that through natural resource materials.

OK: The materials you choose for your work have a very political charge. When you source these materials, do you run into ethical paradoxes that validate the very statements you’re trying to make?

WR: Yeah, a little bit. A lot of my work is about studying materials. Most of the work is done before I’ve made the art—in research, in testing the materials to see what they do. Sourcing them isn’t usually an issue. I got some crude oil from Texas, which was pretty strong stuff. It’s very toxic and very difficult to work with. It brings the reality right in front of me as to what these materials are capable of and what they’re used for. It definitely makes me think a lot more. It piques my interest about the uses of these materials—titanium, dust, silicon.

OK: It must get pretty dangerous to work with these materials, especially [crude] oil. What kind of environment do you have to be in to work with these materials?

WR: When I got the [crude] oil, I didn’t want to use it much. I would be uncomfortable working with it. We used very small amounts of it. We put it in resins to help try to tint them and give them the look that I want to reference crude oil. When I use the coal, we have to wear respirators.

OK: It seems like a lot of the products we use today are made by some kind of crude oil.

WR: That’s what is interesting for me. When you strip everything down, it comes down to these elements on the periodic table. Without that, our life wouldn’t be where it is today.

OK: I want to talk about the Cadillac made from paper towels. It was made shortly before GM recalled ten million of their cars. It brought attention to their negligence and cover-up of it. It’s the same with a lot of car manufacturers. Did you feel this recall was a confirmation of what you were saying? Were you surprised?

WR: I was exploring the Cadillac as an American symbol of power. But power is fragile. I took two commercial symbols. The paper towel is disposable, mass-produced, and convenient. The Cadillac is the symbol of American power from the industrial revolution. Combining the two, I was playing with appropriating these symbols of commercialism and power. What happened with GM is certainly related to what I’m exploring, with this piece especially. Negligence stems from mass production that stems from a system that relies on the speed of consumption. Things are made in negligence and silence, all to make profit. That’s what it seems like. I’m trying to make sense of all this for myself.

"I’m not trying to take a stance on it or have a really strong activist message. I’m coming from more of a fearful place. I do these things because I have a lot of fear."

OK: It’s a complex time. It’s hard to ask questions in a way that makes sense, because it seems like nothing makes sense.

WR: When it does seem like it makes sense, it seems too simple. There’s got to be more to it, but often there’s not. When you’re playing with materials, you see the significance of the materials.

OK: The Situation Room, which is going to be a piece in your next show, is a good example of that. Why did you choose to use coal?

WR: First, I wanted to take away all the colors and emotions from that photograph. I wanted to take away any kind of nationalism and romanticism that was there. I wanted to use a monochromatic material that was also a resource. Oil would be an obvious choice, but coal was more interesting to me. The interesting thing about that piece to me is the situation itself, not the event. It’s not about Osama Bin Laden or 9/11. It’s about a much bigger situation that repeats itself throughout history. Coal is referencing that, as well as redaction. If I saw the Situation Room, and it was covered in crude oil, that’s too direct and obvious. I would walk away. I would think that I saw something that looked cool, but was something I already knew about. With coal, I walk away thinking about a lot of different things. I think about history. I think about Pompeii. I think about archaeology. I think about energy, power, and expansion during the industrial revolution. I think about when American interest became very aggressive with the Middle East, which was around the time of the industrial revolution. I think about oil replacing coal as an energy source. I think the arc of this. 9/11 and the incident itself on Bin Laden’s compound was just one letter in the entire alphabet.

OK: From a historical sense, it’s such a fresh moment in history that we glance over that photograph as iconic. There are so many of these iconic, photojournalistic moments in history that have come up in major magazines that have now solidified major political conflicts. If you were in a different time, could you think of one photograph that would influence you to make a sculpture?

WR: There are probably many. I’m not really sure. There are many photographs that make me think about things. What I found interesting about this particular photograph was the relationship between propaganda and what’s underneath all that. A lot of these photographs operate that way. The Vietnam War was photographed a lot and on television a lot, which is why people were so aware of it back in the States. Without photographs and television, no one would have known. The Gulf War was the first war that was live. It was like a video game.

OK: I remember that—night vision images of bombs exploding.

WR: Television created a reality. Shortly after that, reality television became the number one media. There are similarities in all these relationships. That’s what interests me. When you see the Situation Room sculpture in person, I tried to make it as exact and as honest I could in relation to the photograph. When you see it—I didn’t do anything to it other than making it 3-dimensional and out of new material—I took everything else away. You see the difference. You can feel the intensity. It makes you think. Why was the photograph released? Why was everybody looking at that?

OK: Another big theme that you work with is human commodification, which is a big deal right now. Terms like “human resources” are thrown around when they should not be applied to humans in a working setting. How extreme do you feel this thread is? Do you feel we are approaching a society fueled by Soylent Green?

WR: I’m not trying to take a stance on it or have a really strong activist message. I’m coming from more of a fearful place. I do these things because I have a lot of fear. What helps me along and make sense of everything is to retrace it. Ultimately, what helps is to work with these materials and make these installations.

[In Classroom] One figure is sculpted, cast, and molded twelve times; there are twelve identical figures. Each one is made from a different material. They’re all natural resources, like salt, wood, chrome, titanium, gold leaf, and copper leaf. They’re all materials that have been essential—and are essential—in building our economy, retail, technology, military, and energy. All of those elements are in this piece. They’re the same figure, but because each is made from a different material, they have different characterizations, identities, and personalities. They all look different, which is interesting, because they’re all the same. We’re all the same, but we experience each other. The differences in each piece are purely from the materials. Some of them look Asian, some white, some African. The material has washed away some of the features. I really think that’s interesting and telling.

That’s a sign of mass production. I was thinking about that when I was working on them. I arranged the child-like figures into a grid that was reminiscent of an assembly line or military formation. The idea is that human beings can be mass-produced. They are just as much a resource as titanium or silicon. That’s interesting and disturbing. It’s part of the paradigm of the system that we live in. I don’t know if it’s bad for the majority of people. It’s great for a small amount of people. It’s what we live in the United States. That’s why I want to figure it out.

Also, robots are replacing humans. You see pictures of car factories—robots are building all of these cars now.

OK: Should we be fearful, or should we be hopeful for the future?

WR: I don’t know. I’m coming from an honest and accepting place. I think I’m hopeful, especially when I do this kind of work. It makes me hopeful. I feel like I understand things better. It’s such a complex, complicated machine.

Will Ryman's Two Rooms opens on September 10 and runs until October 17, 2015 at at Paul Kasmin Gallery, 515 W. 27th Street. Profile photograph by Dan Bradica. Text and interview by Oliver Maxwell Kupper. Follow Autre on Instagram to stay up to date: @AUTREMAGAZINE