interview by Abbey Meaker

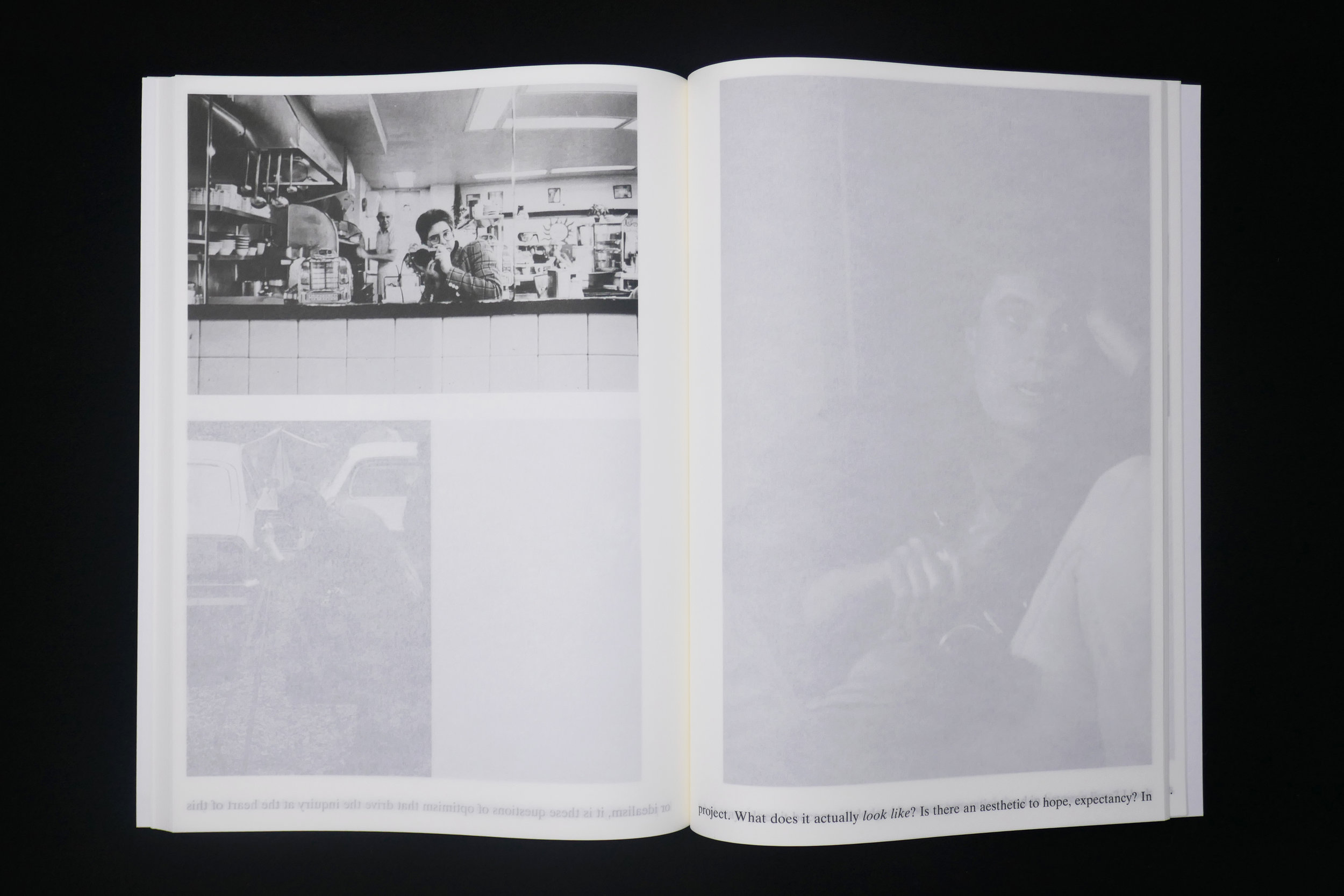

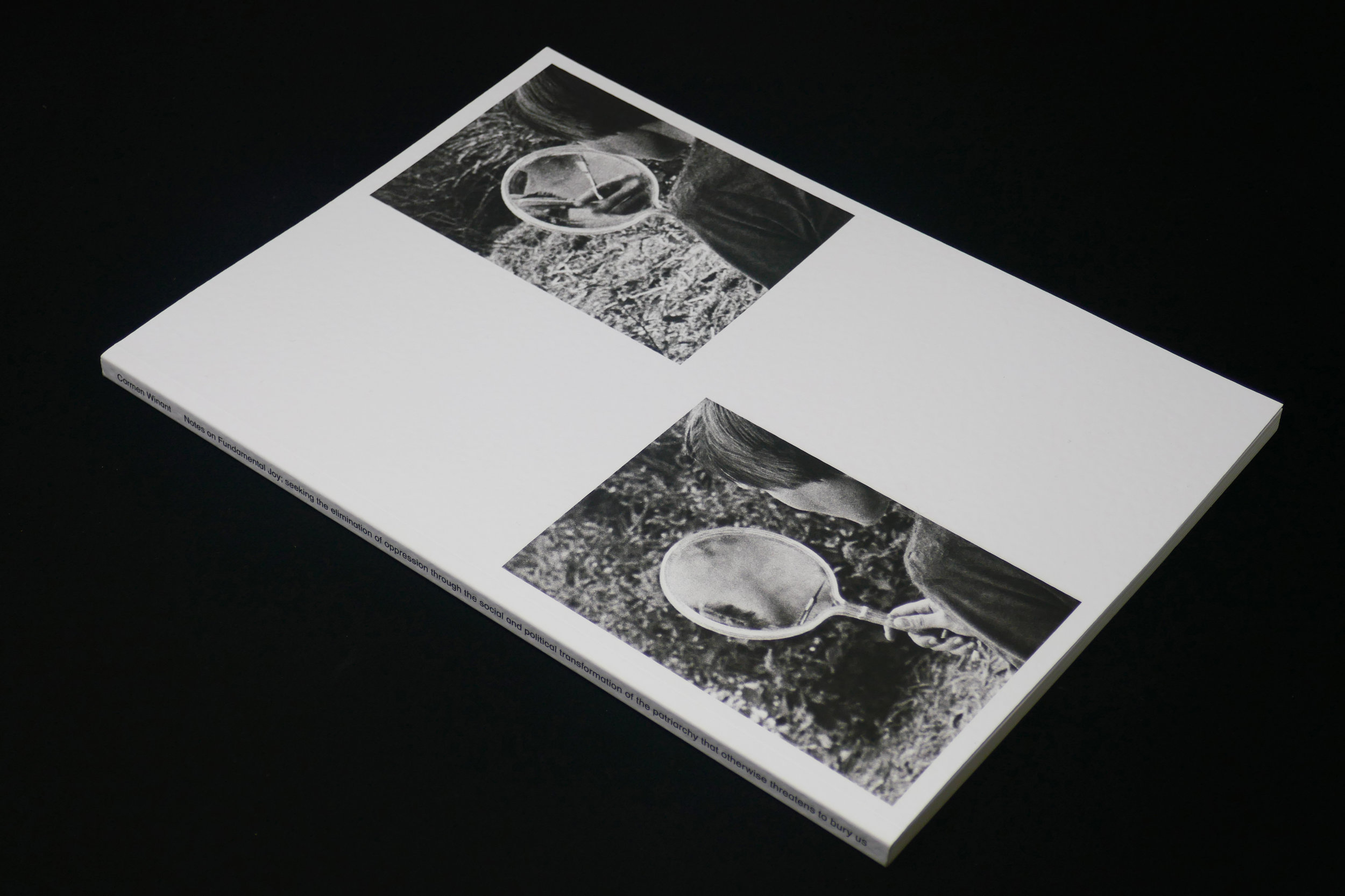

In her new book titled Notes on Fundamental Joy; seeking the elimination of oppression through the social and political transformation of the patriarchy that otherwise threatens to bury us, Carmen Winant offers a poignant question: Does hope have an aesthetic? If it does, you may find it within the pages of this provocative book.

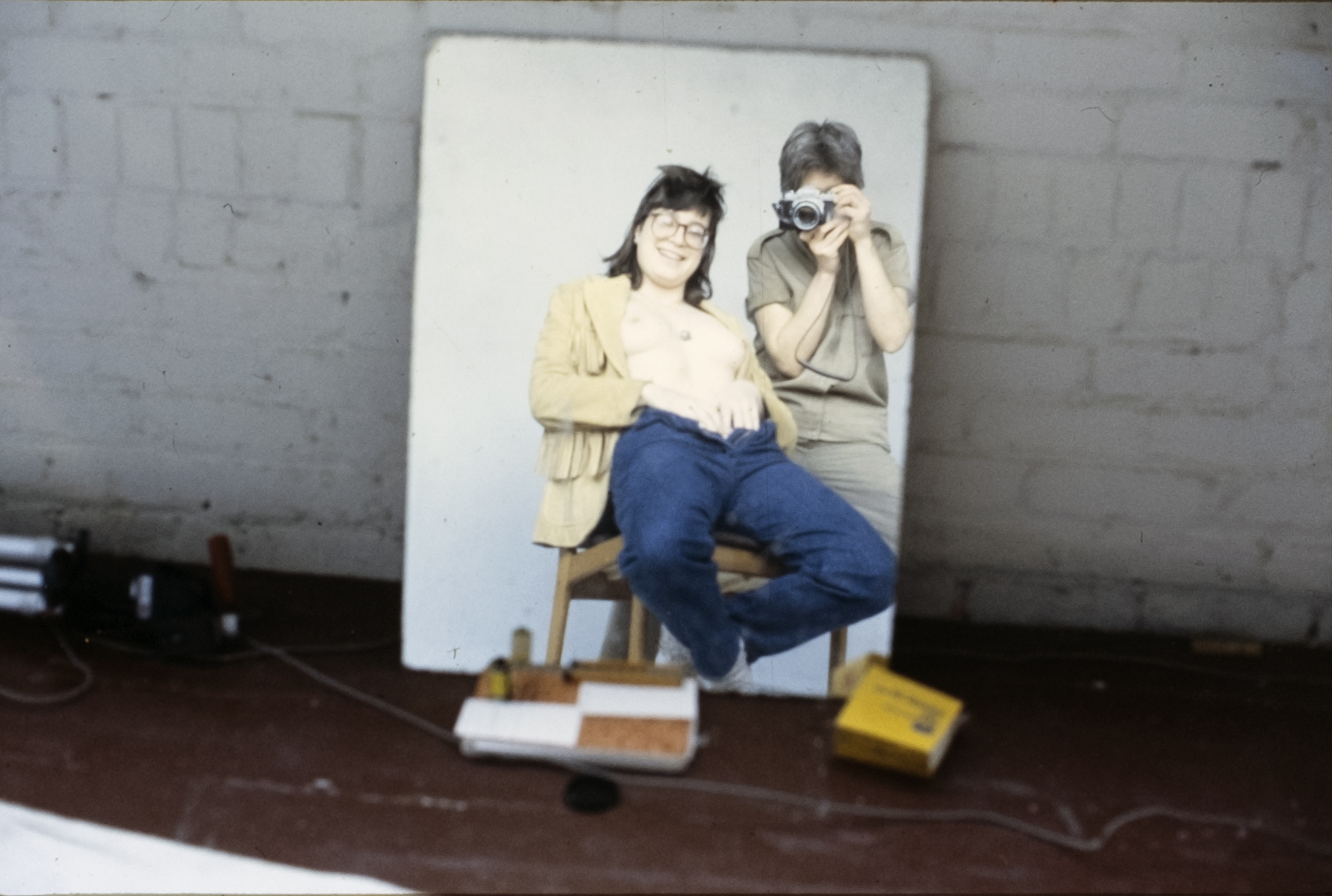

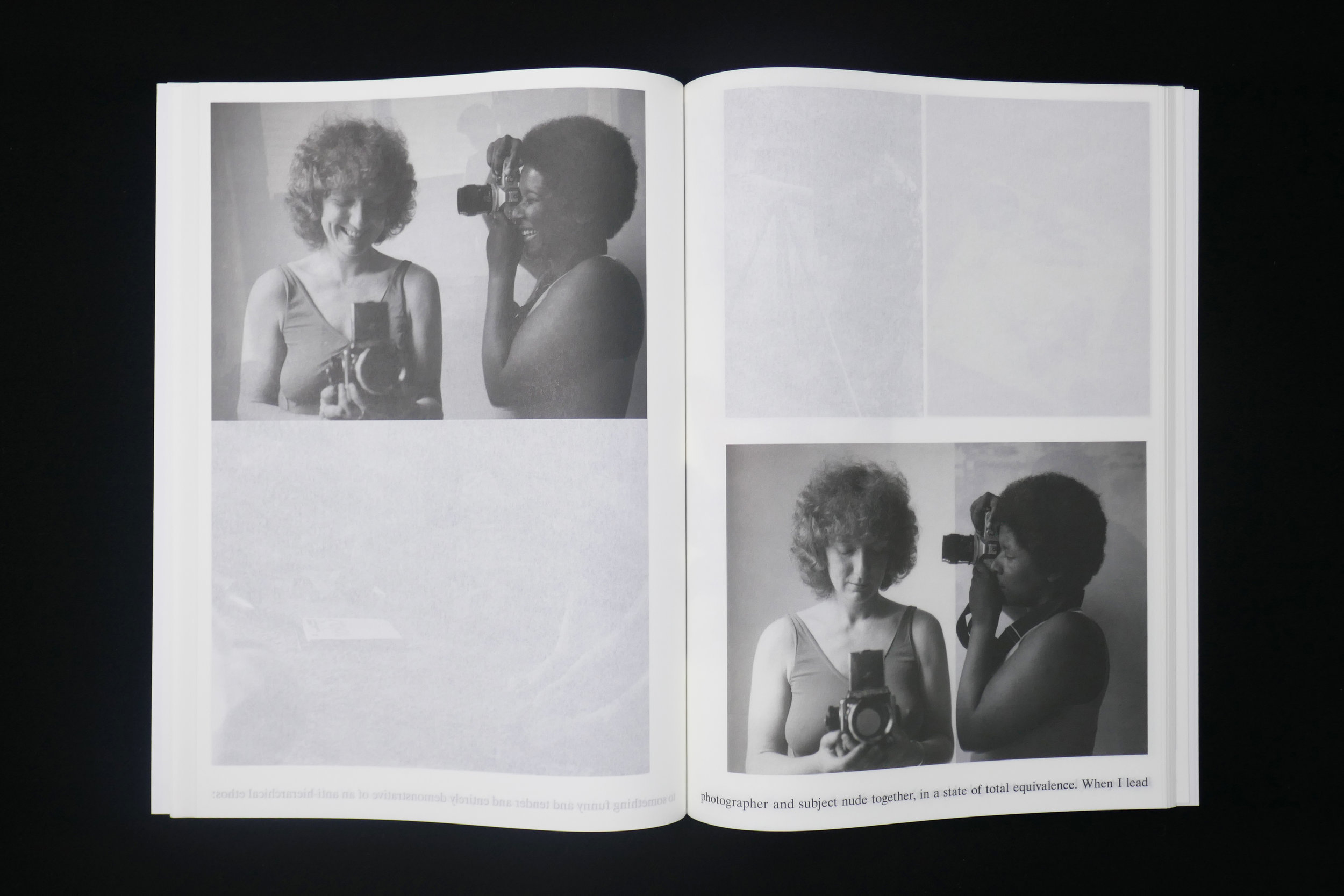

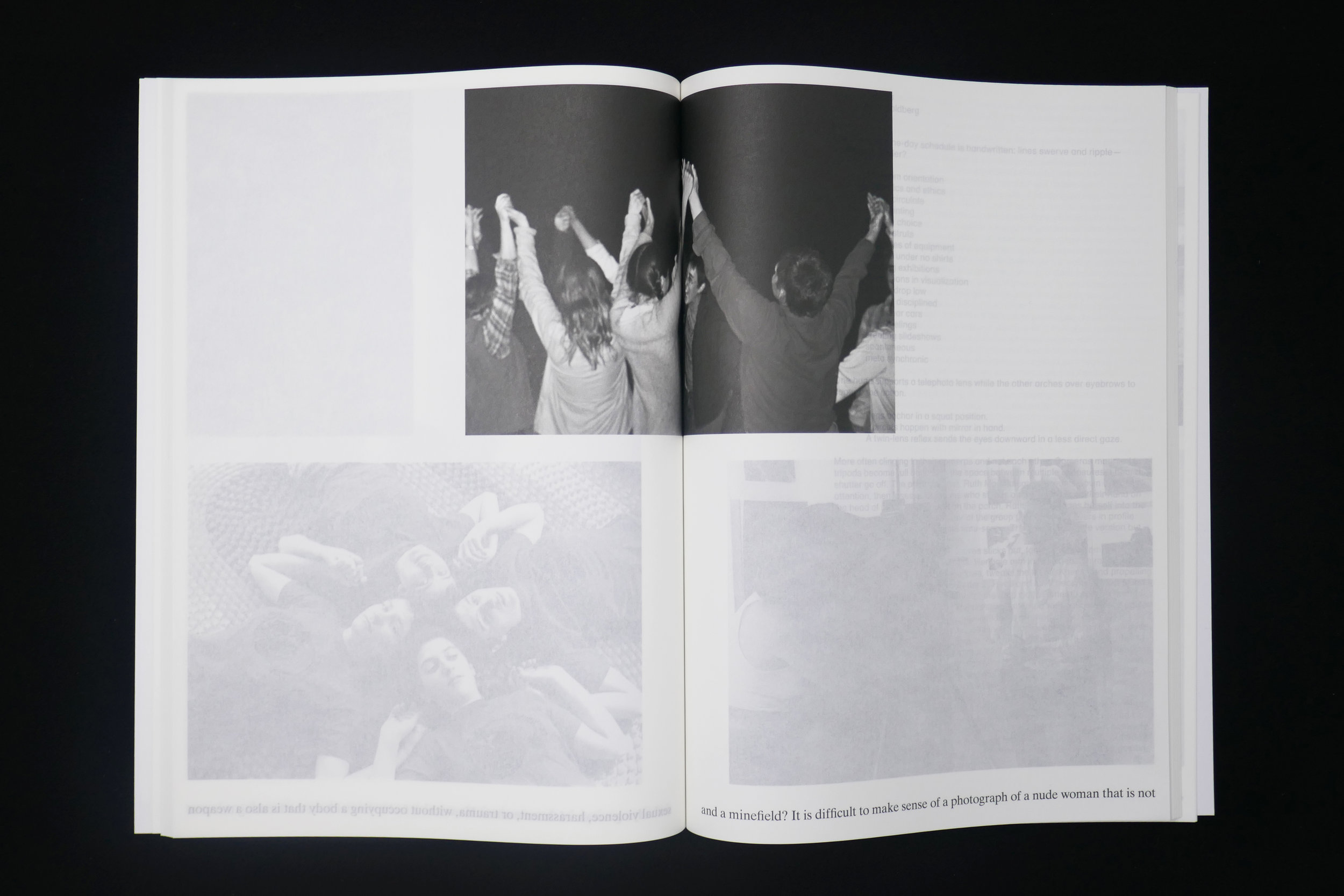

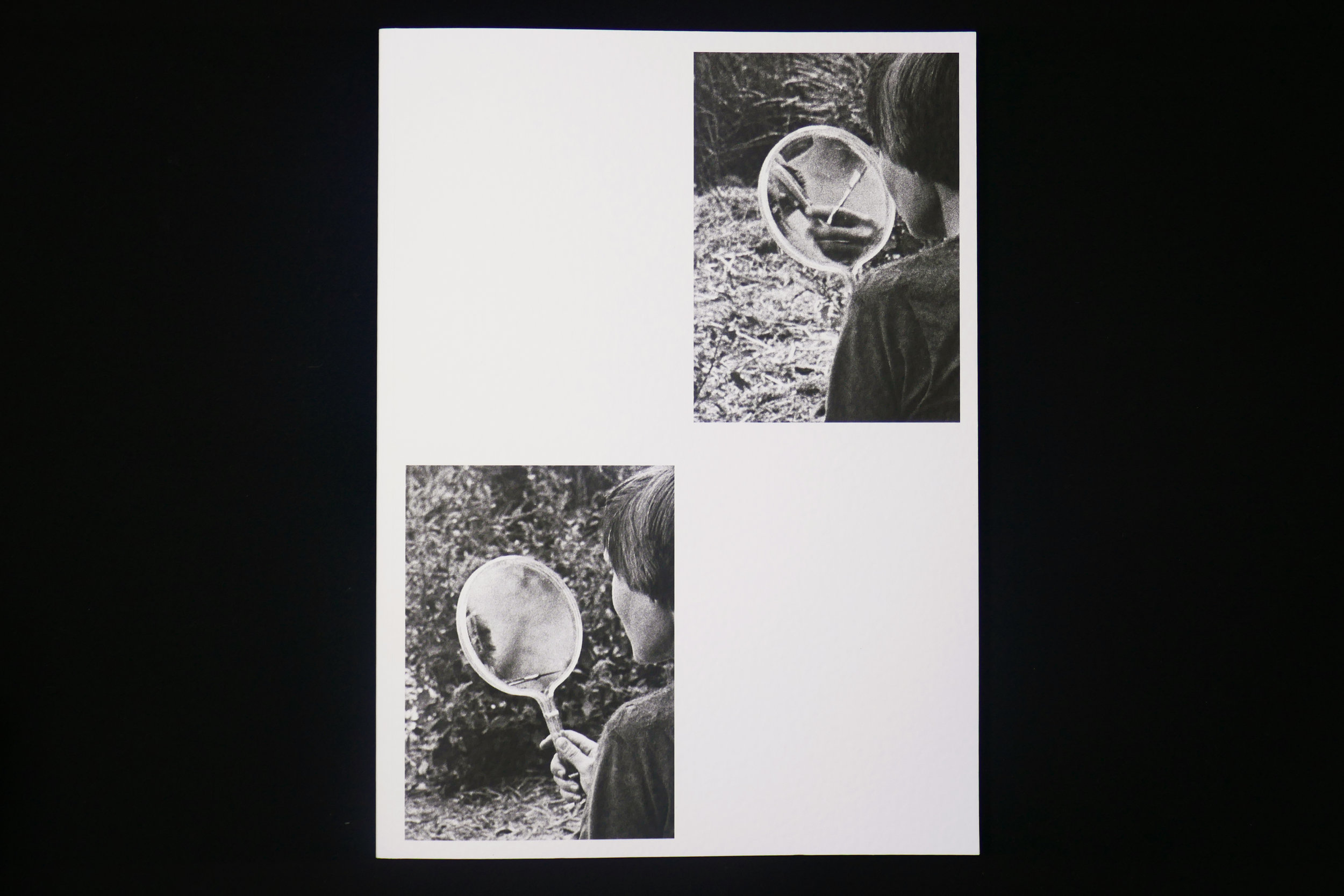

Designed by Jena Myung and published by Printed Matter Inc., the book is both an artist’s project and an historic collection of found images, photographs whose function was not only to document women-only communities formed in the 1980s across the Pacific Northwest, but also to subvert the pervasive dynamic in photography of man as subject, woman as object. Through these photographs of an almost unfathomable utopia of feminist & lesbian separatists, we can contemplate a world that exists outside of patriarchy. A safe, inclusive, fantastical space in which art is central to community making, connection, experimentation, and purpose.

Meaker: Can you talk a little bit about the title and how you feel like it was relevant at the time the photos were made and how it’s relevant now?

Winant: Part of the reason that I gravitated towards this material in the first place is because it held such promise and joy. I’ve known photography to occupy a space that can be more severe or competitive. The women photographers I idolized as a student, people like Francesca Woodman and Diane Arbus, all killed themselves. It wasn’t just that I felt that it was difficult to be a woman in the world. I also understood photography as entangled with that problem, that it was violent and incurred violence onto bodies, and onto the photographers themselves. And when I encountered these images, I felt inside them a whole new kind of promise—something that was bound up in the word joy, as well as world-building in this case of stepping outside of patriarchy altogether, and using photography as a new way to see the world. That felt really powerful. I was starting to do this research during the presidential campaign. It’s not a far reach to understand why I felt I needed to move towards not subverting the patriarchy from the inside, but instead looking at people who had just left it all behind. I understand that now that that impulse came from being confronted with the ugliest parts of our patriarchy. For me, the project is tethered to that moment in historical time.

Meaker: Looking at these images and thinking about these communities in the ‘70s and ‘80s, is it discouraging to know where we are now, and see that it failed in a way? Or did it?

Winant: Yes and no. When I first encountered the images, I had the same binary logic around it. But the longer that I researched, I started to feel that there was more nuance in this question of what it means to succeed and fail. There were so many thousands of women that cycled through these women’s lands, and even if the community ended up dissolving, that consciousness still permeated into those bodies, and that sort of changed the way they lived their lives, how they moved through space, how they related to other people, how they engaged with politics, community, relationships, child rearing, and so forth. This is what coalition building is. It’s messy, it’s difficult, people get pissed off and leave, and it’s not built to last. But that doesn’t mean that it hasn’t succeeded.

Meaker: Totally. When looking through the book, I felt that it was a fiction. It’s so hard for me to imagine existing in such a utopic place, free of the critical eye of white cis men. Man-as-subject, woman-as-object is such a pervasive dynamic in photography. Why do you think that photographs were central to these communities, and do you think it served as a medium of documentation as well as a kind of rebuttal?

Winant: Definitely. And let me address the first thing you said too, which is the fantasy element of it. So much of my own relationship to this material is really romantic, and I brush off the things that don’t feed my fantasy, like the conflicts that happened, and the wars they lost with the landowners, and the bank, and the disabled women who left because there wasn’t space for them to survive in the country. Not to mention how few non-white women there were, and non-middle class women. It took me some time to come to this, but I realized that this is a part of the project, to follow the discordances. The way I teach feminism is as the prospect of world-building, and the imperative of a feminist is to imagine that a different world is possible. Without that imagination, we have nothing. We have no values, we have no politics, and we have no essential selves if we can’t imagine something outside of the world that we’re living in, or living under. And so, I think it’s really important to think about my own feminist politics as kind of revolving around that promise.

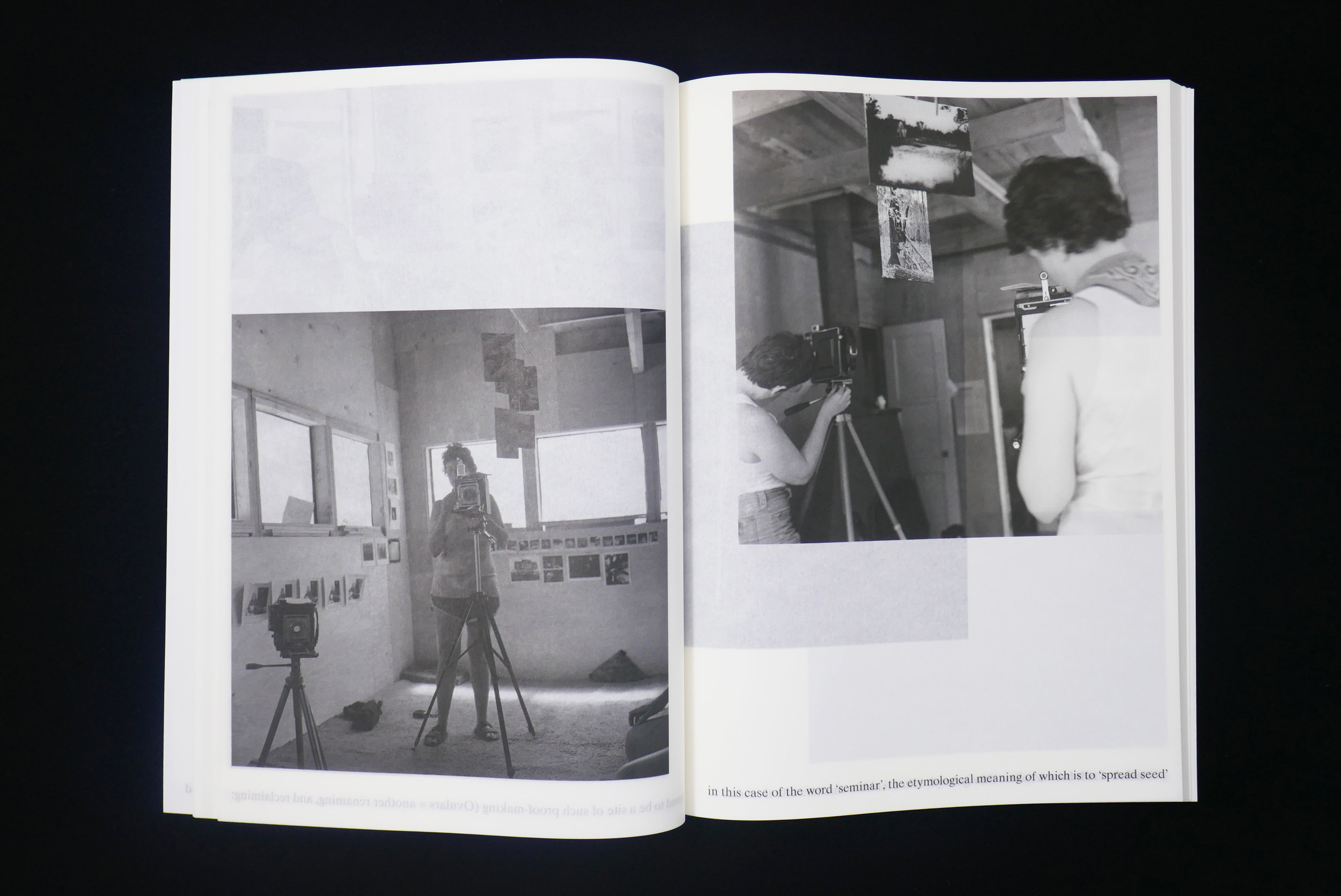

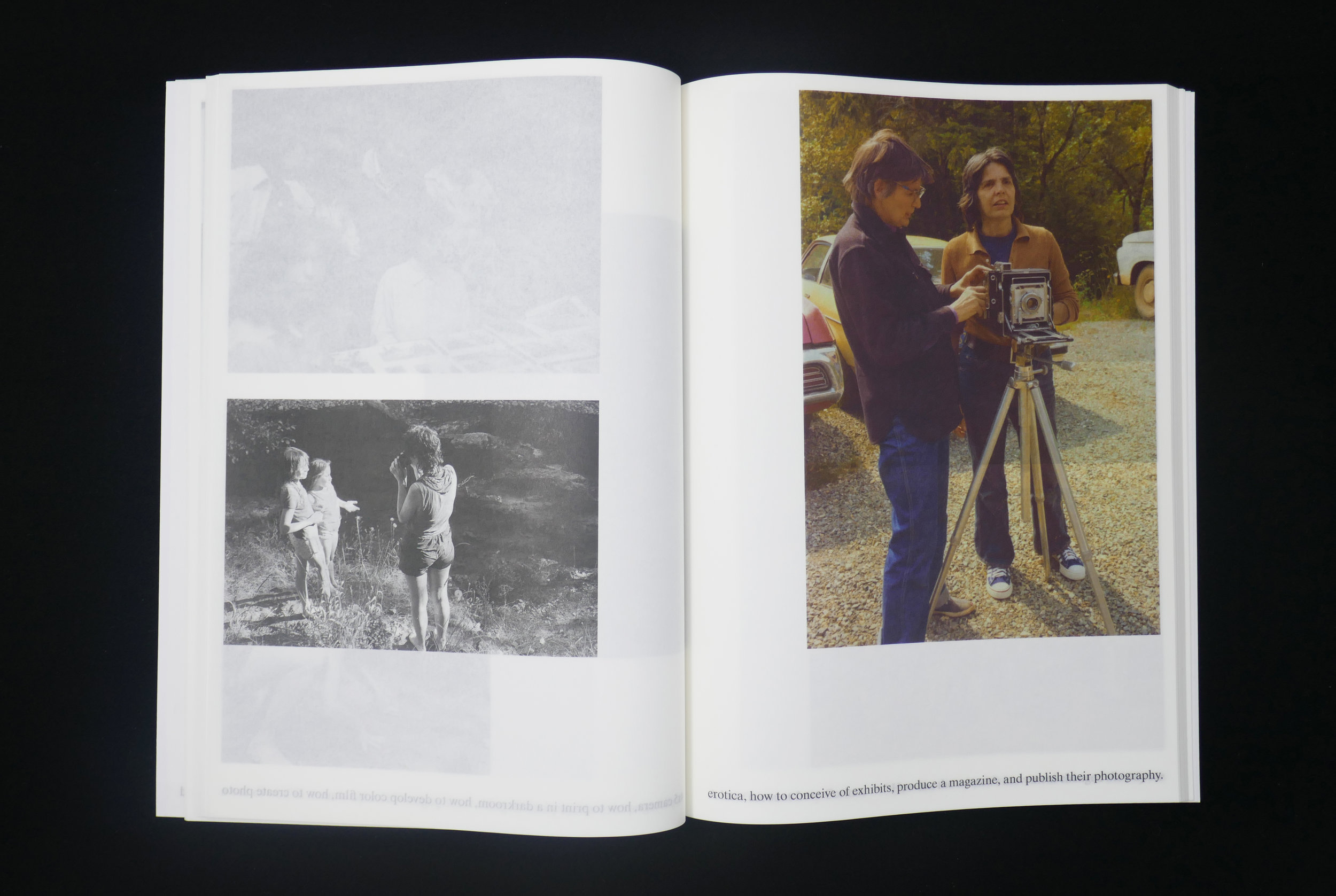

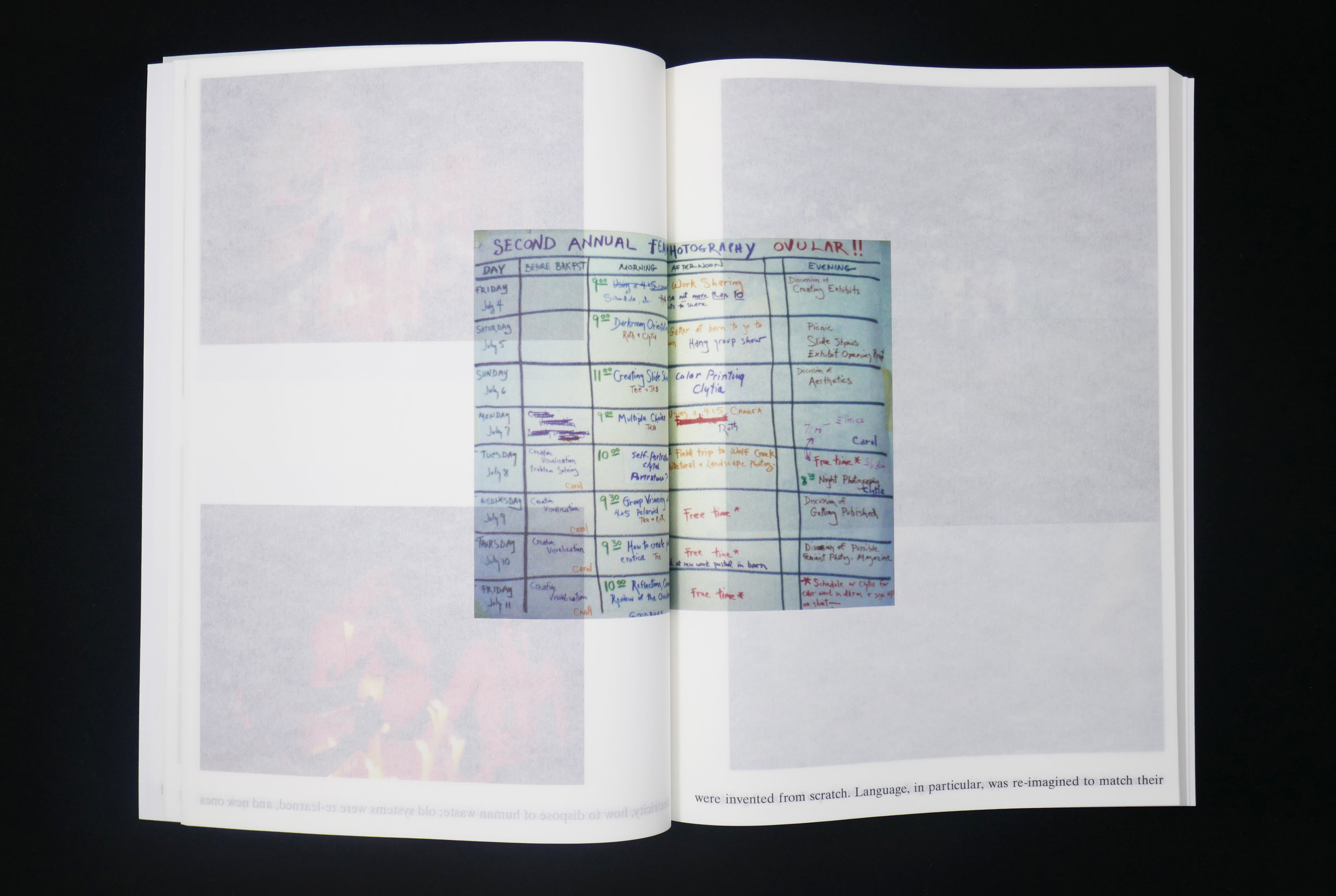

A lot of the different women’s lands built wet darkrooms, although the book in fact revolves around the ovulars, which are these photographic workshops that were offered on one particular women’s land, which was called Rootworks, in Oregon. An ovular is a take-off on seminar, which means the spreading of semen, etymologically. So, they instead called them ovulars, and the women who took them were called the ovulators. It was a new way to see themselves, and each other; to reframe desire, and kinship, and affinity and self, and sight, and insight, but also to stand as evidence. When so many of these women came out as gay, they were kicked out or they were left with nothing. Some of them had their children taken away from them. They had no evidence of their lives, in some sense. So it existed beyond the metaphoric idea of needing to reframe the way we see, and into something quite tangible, about how to make new evidence of our lives in this state of being reborn.

Meaker: Knowing that it was probably finite.

Winant: It depends. When you read their accounts, some women feel as though it will last forever. And others that are far more skeptical are dipping in and out. So, I think there’s quite a big range.

Meaker: Did the women teaching the workshops come in as photographers, or did that come from being a part of the community?

Winant: So far as I know, there were six different organizer midwives that cycled in and out. They all went on to become pretty serious, and I think they were pretty serious already. They still remained on the margin, but they were dedicated photographers. The ovulars ranged from technical workshops to making lesbian erotica, or how to make photographs about love and sex.

Meaker: I love that art making was such a central activity.

Winant: It really is difficult to live in the country, particularly when you are arriving with no skill about how to irrigate, how to you know plant food in the ground, or how to build structures. The fact that they carved out the space for this kind of production feels really critical.

Meaker: How did you happen upon this work, and when did you know you wanted to do something with it?

Winant: Years ago, I read an article in the New Yorker by Ariel Levy, and it was about the Van Dykes, who were a separatist community. I just remember feeling so amazed by the prospect of this. My work has been about looking for another world, and trying to imagine a world outside of patriarchy, so to come across this felt revelatory. I started to get deeper into it and I discovered this vast photography archive, and I was amazed. They felt like such important historical documents, and were also incredibly striking photographs. The project is an homage to these communities, as well as a platform to make the photographs exist in a public space together.

Meaker: These women were unknown, and you were naming them and crediting them. So many women artists are subsumed by their male contemporaries, so this was exciting to me. In your last book, My Birth, many of the photos are anonymous.

Winant: Yeah, all of them, in fact. That was really different in this project. Normally, the way that I work is I gather the images that I want, I remove them from their sources, I re-contextualize them, and I call it fair use. That was never going to be an okay way to work here for a couple reasons. It wasn’t possible administratively, but it also wasn’t possible to do in good conscience. These are art objects. We got the copyright for every image, we paid the artist for the image if they were alive, and we got permission to reproduce. To be honest, I’ll probably never work this way again because it was so time-prohibitive. Sometimes I spent days just trying to get a single image.

Meaker: And did you always imagine it as a book?

Winant: No. At first I thought it could be an exhibition. But as I was thinking through possibilities, Printed Matter reached out to ask if I wanted to make a book. I thought that that could be an interesting way for those photographs to come together. I’m delighted it’s in the form that it’s in, in part because in the archive, many of the photographic objects exist in some sort of magazine or pamphlet. It doesn’t exist as a conventional photographic archive, and so a book really made sense.

Meaker: It feels so intimate too. It’s nice to hold it and touch as an object.

Winant: I’m so glad you say that. We spent a lot of time talking about that.

Meaker: What attracted you to such era-specific imagery from the ‘70s?

Winant: I think there are a couple ways to answer the question, the first being that that era is where so much printed matter lives. There is an enormous glut of books that are published from the late ‘60s through the early ‘80s as a certain personal-is-political kind of feminism comes to bear. Those books are replete with photographs. That doesn’t exist in the same way anymore. But it’s more than that, of course. So much of my interest, conceptually and politically, as a person and an artist, is about working to understand the feminism that begot my feminism, the history that begot my history, and the space between us. I look at the feminism that belonged to my mother’s generation, and it feels, in some ways, so foreclosed. My work has always been about trying to reach backwards and understand what it means to inherit a memory, what it means to reckon with the idea of women’s liberation fifty years later.

Meaker: And how do you think it changed?

Winant: It changed in so many ways. Regarding the name “women’s liberation,” I don’t think that we, for the most part, believe in the idea of liberation anymore. We don’t belong to radical feminism anymore, and we can understand that by looking at these photographs and understanding that they look like a fantasy to us. There are so many different qualities that have shifted, that have made it more progressive, and more inclusive, and at the same time, I mourn the loss of those things that I mentioned.

Meaker: The photographs in the book are of naked women, and their bodies all look similar. The world that is depicted in the book feels inclusive and safe, but the images of the women aren’t. How did that sit with you when you were bringing together these photographs?

Winant: There’s another scholar who’s done some research into the ovulars. His name is Andy Campbell, and he’s a professor at USC. He's said in a talk that I noted, “To leave everything behind can be a privilege.” I think, in some cases, he’s right. There’s one African-American woman who appears over and over in the ovulars. Her name is Lynne Reynolds, she lived in Brooklyn at the time. I’m always so struck by her presence in that place; she stands out as the only nonwhite participant, as far as I can see. It reminds an onlooker that there is an issue of who has the ability to participate in the first place. The ovulars were absolutely incredible for their radical inventiveness, for the creatively, for their dedicated feminism. I admire them from deep down. And they also make me wonder: who has the ability to leave it all behind?

Meaker: To me, your broad practice has recurring themes relating to origins, materiality, the fecund body, and also, a drive to subvert the notion that the pregnant body is the ultimate representation of abstraction. In your book My Birth, the photographs are really aggressive and they demand to be seen. At the same time there is desensitization in the repetition of the images. What are your thoughts on that?

Winant: After I gave birth the first time, I was amazed, horrified, delighted, and terrified at what that experience had been. So much of how I relate to my experience is to try to make it intelligible through photographs, and it became very clear to me very quickly after giving birth that I couldn’t do that. It’s not that there were no photographs of birth, but there were vacuums. I didn’t recognize it anywhere in contemporary art, for instance, with very limited pockets of examples. I think some of the work was intended to fill up that space. But in a larger way, I understood that there was not going to be any photograph that would be able to account for that experience as fully as I wanted it to, for all of its sensate abjection. Part of the repetition was about working to insist on that image over and over, so it could be seen and knowable, and at the same time, doing so with the distinct understanding that it was a failed premise.

Meaker: And where do you think the new work fits in with that?

Winant: It was an incredibly agitating experience to look at bodies opening up and pouring out. I needed to look at something that felt unabashedly joyful. It was important for me to find images to live with that occupied a different experience, a parallel experience.

Meaker: You pose a question in the book, which is, is there an aesthetic to hope? And I wonder if this project has offered an answer to you.

Winant: At the beginning of this project, I wrote a single note that I put above my studio desk: what does a free body look like? And I think there are a lot of different questions in that question. Do pictures look different when women make them? In that sense, do women have a different photographic aesthetic? Do lesbians? Do feminists? What does joy look like? How do we see it? How do we frame it? I’m really interested in the relationship between politics and aesthetics. These photographs feel so distinct, yet they have such deep echoes of one another that I have to ask, how has this experience actually changed the way that they see?

Meaker: Maybe it’s more a feeling than an aesthetic.

Winant: Definitely. That can be a really difficult thing to account for. As an artist, how do you come to learn and occupy a photographic feeling?

Meaker: I think maybe it is an innate ability, because not all photographs have that.

Winant: I agree. It is innate to a person, but also to a place and a moment in shared historical time.