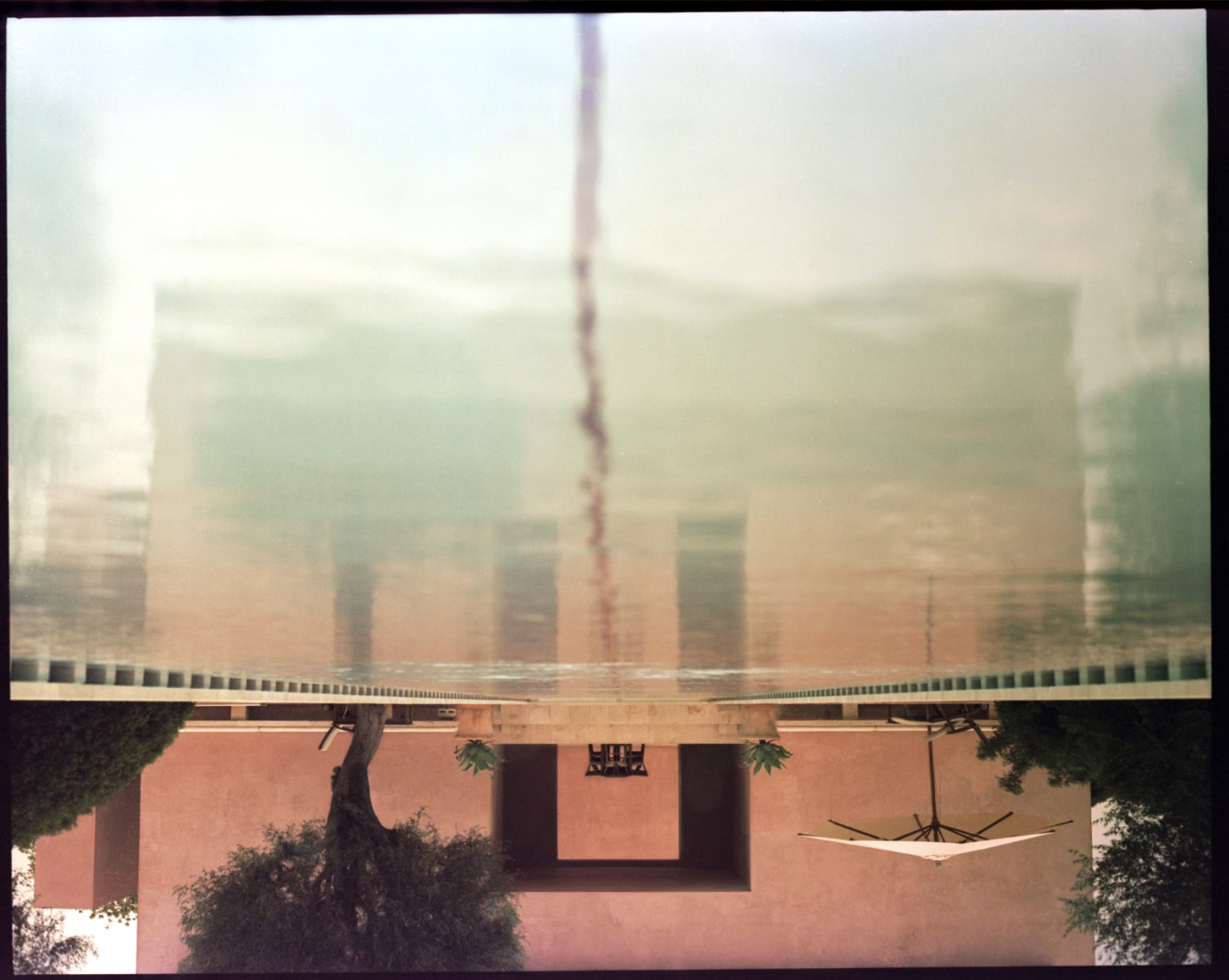

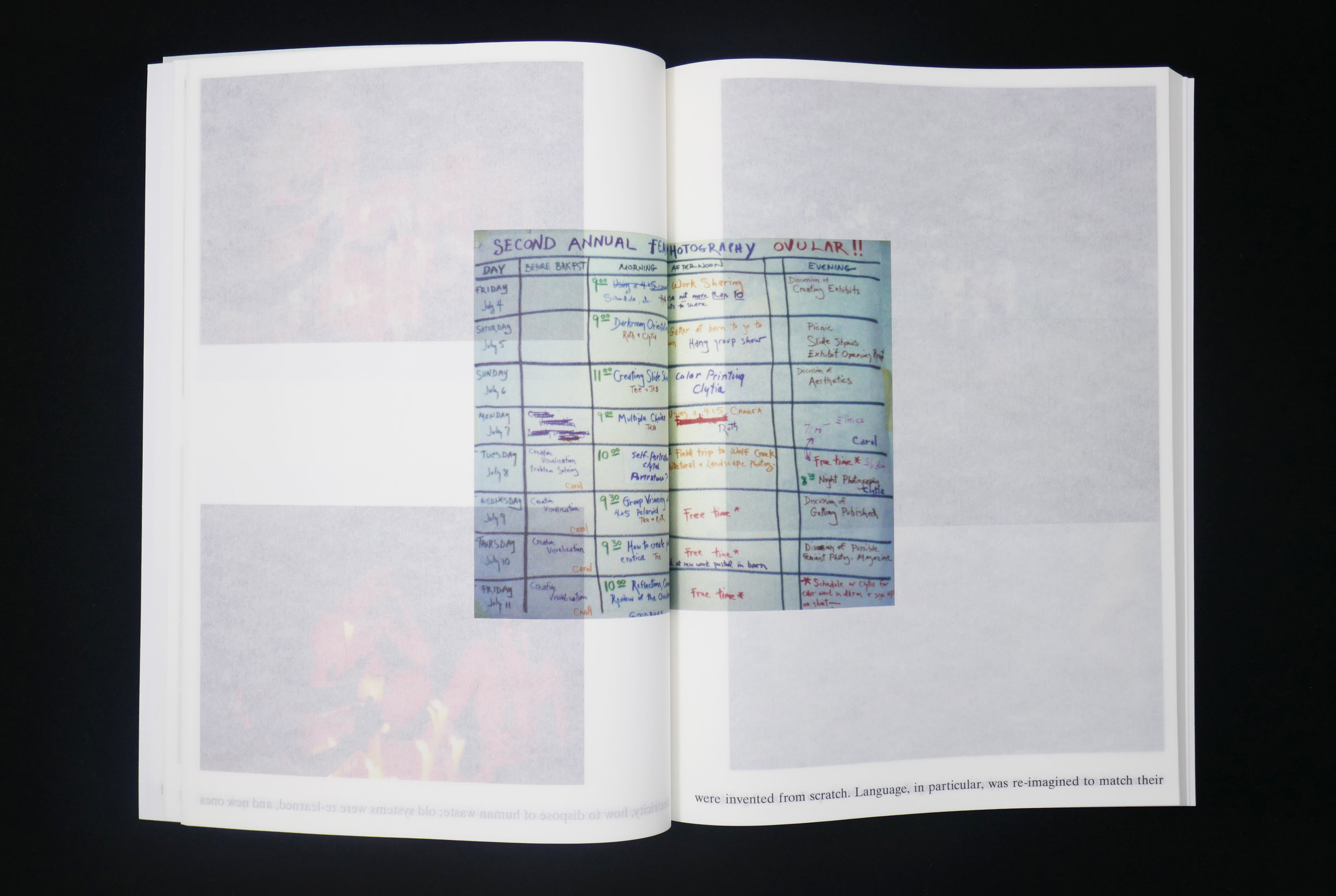

Diane Arbus, Constellation, 2023–2024, The Tower, Main Gallery, LUMA Arles, France. All artworks © The Estate of Diane Arbus Collection Maja Hoffmann/LUMA Foundation. Installation Photo © Adrian Deweerdt

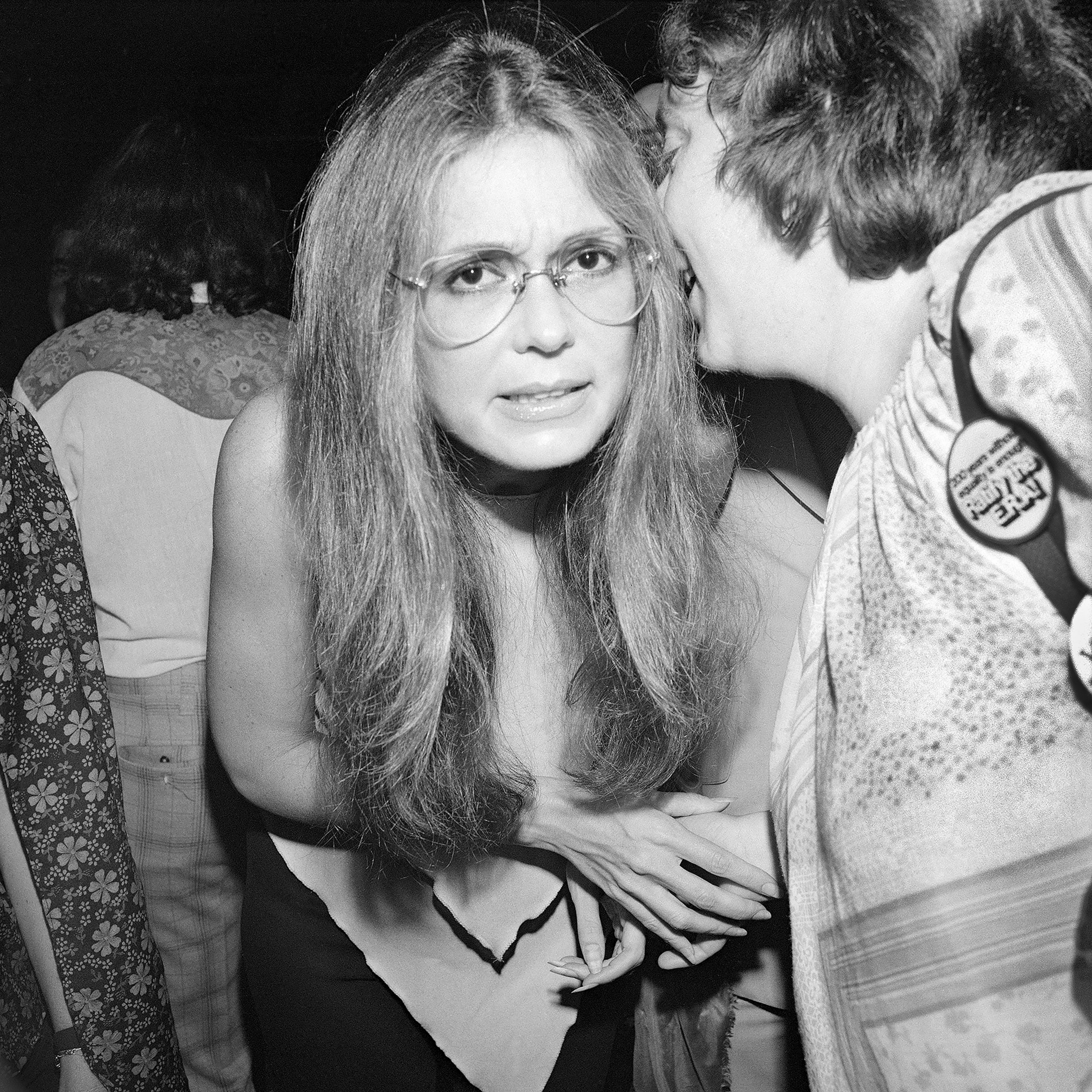

text by Kim Shveka

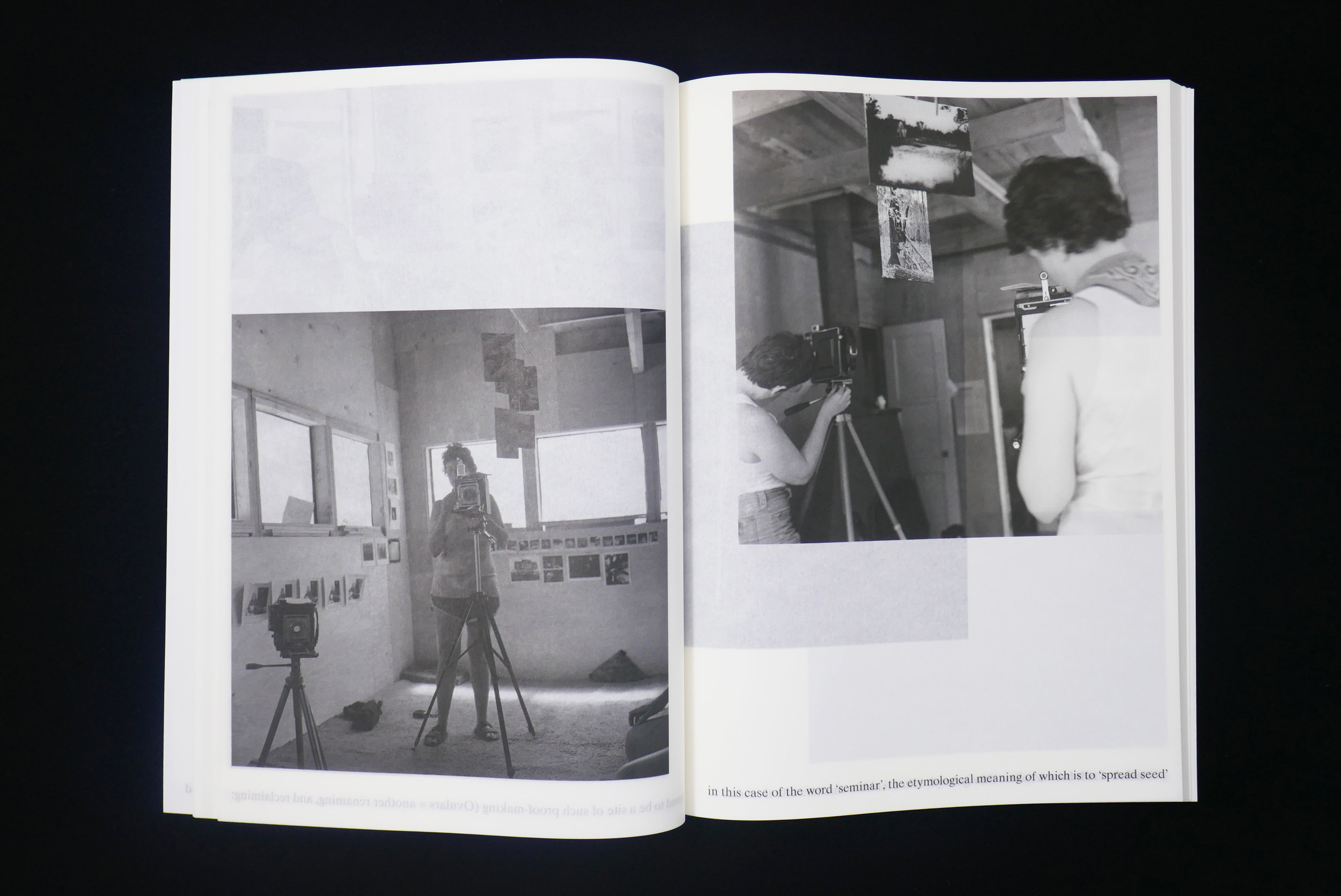

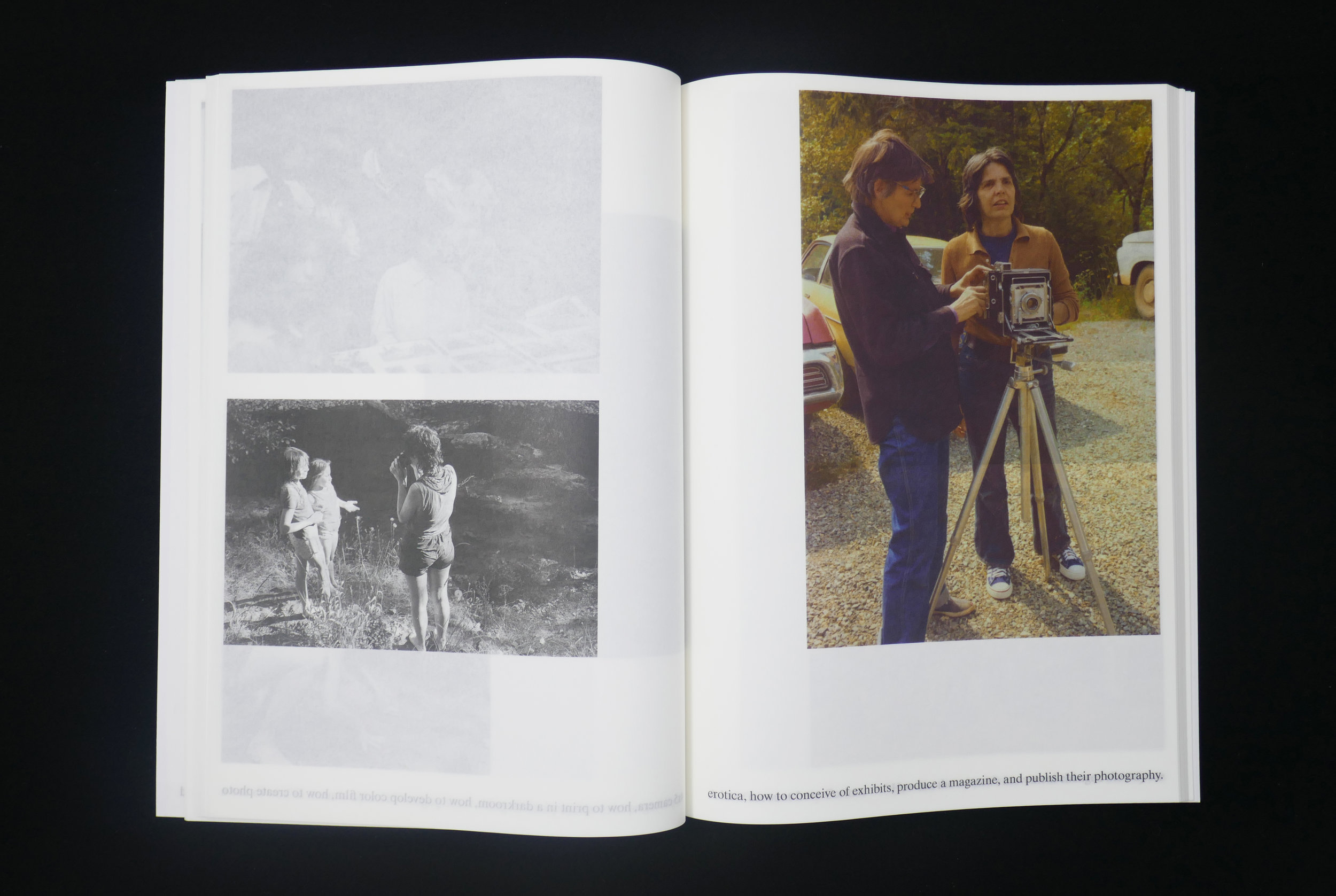

Diane Arbus’s photography has long unsettled and fascinated viewers, defying easy interpretation. In Constellation, the newly opened exhibition at The Armory, curator Matthieu Humery brings a second life to her work; not to explain or categorize, but to invite quiet, intimate dialogue between the viewer and the photographs. Featuring 454 photographs from the artist’s archive, including many rarely seen, the exhibition defers any chronological or thematic structure, favoring a layout without linear direction, making every encounter entirely unique and unpredictable. The experience is haunting, dissociating the viewer from the fact that they’re in an art show, and instead allowing them to sink into provoked emotions, completely immersed in an entirely human experience, dissolving the distance between audience and the subjects.

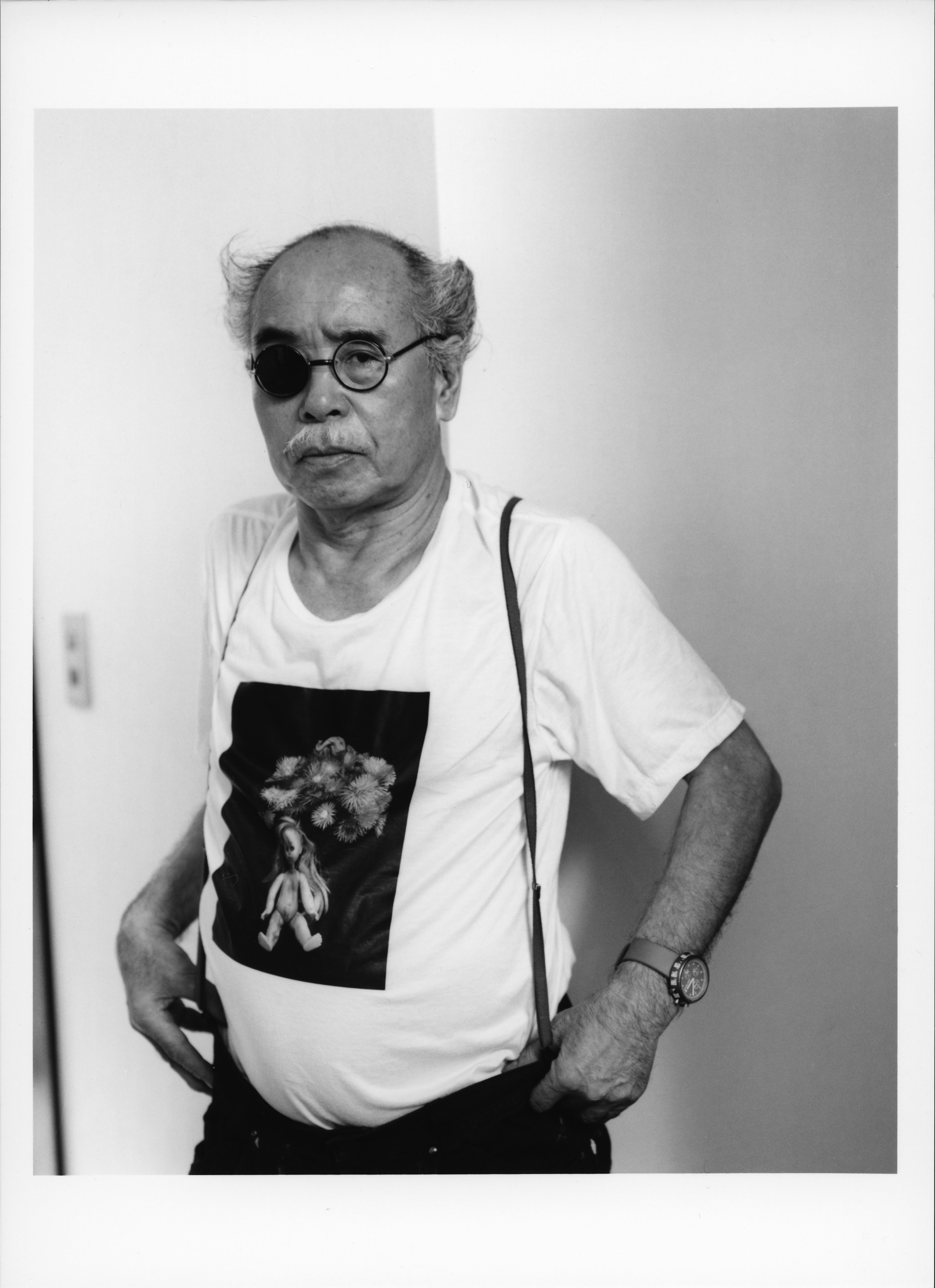

In our conversation, Humery shares what it means to curate with restraint, how working with a posthumous body of work introduces both freedom and distance and what it felt like to place each image by hand in the space, listening for their rhythm.

KIM SHVEKA: Arbus’s work has often been misread or misused, sometimes seen as too voyeuristic. How did you approach this complexity in your curation?

MATTHIEU HUMERY: What I really wanted was to find a way to present her entire body of work without interpreting each image individually. I deliberately avoided passing any kind of judgment, neither my own nor anyone else’s. Instead, I wanted to create a system that would allow all 454 images to be seen together, in a way that encourages the viewer to explore freely and draw their own connections.

The structure of the exhibition forces a certain kind of encounter: one where the visitor must navigate the work for themselves, discover things on their own terms, and confront the images through personal experience. That process of self-directed exploration invites a different kind of understanding—intuitive, intimate, open-ended.

In this context, the photographs that are sometimes labeled as voyeuristic may appear in a different light. Rather than being intrusive, they might reveal something more fragile, even tender. Seen within the full constellation of her work, they begin to feel less like transgressions and more like windows into something deeply human. That’s the complexity I wanted to preserve, the sense of a gaze that doesn’t impose meaning, but instead looks back at us.

SHVEKA: You worked with hundreds of unpublished photographs. How did you balance discovery and restraint in your selection? Do you find it easier or more challenging to curate art by a deceased artist?

HUMERY: I didn’t make any distinction between well-known and previously unseen images. My approach was to dismantle all the usual categories, to mix the series, the themes, the formats, and to avoid any chronological or hierarchical structure. I deliberately sought to blur the boundaries, to let the images coexist freely, regardless of their familiarity, their subject matter, or their scale.

As for working with a deceased artist, I’m not sure whether it’s easier or harder, but it is certainly different. There’s always something that escapes us. Death introduces distance: it forces us to reflect on a body of work that is complete, and yet whose interpretation remains permanently open. In a way, once an artwork has been created, and even more so when the artist is no longer here, it escapes its maker. The work survives, but it does so on its own terms.

SHVEKA: In building this exhibition from Neil Selkirk’s archive of posthumous prints, how did you navigate the tension between honoring Arbus’s artistic autonomy and interpreting her legacy through your own curatorial lens?

HUMERY: As I mentioned before, my intention was never to interpret the work, but rather to create the conditions in which each visitor could encounter the photographs and make sense of them on their own terms. I believe that’s the most respectful approach one can take with an artist’s work, especially with an artist as complex and singular as Diane Arbus.

By resisting a curatorial voice that explains or contextualizes too much, I hoped to preserve her autonomy, to let the photographs speak for themselves, and to allow the viewer the space to look, to feel, to connect, and ultimately to decide. In that sense, the exhibition is less about offering a definitive reading than about opening up a field of possibilities

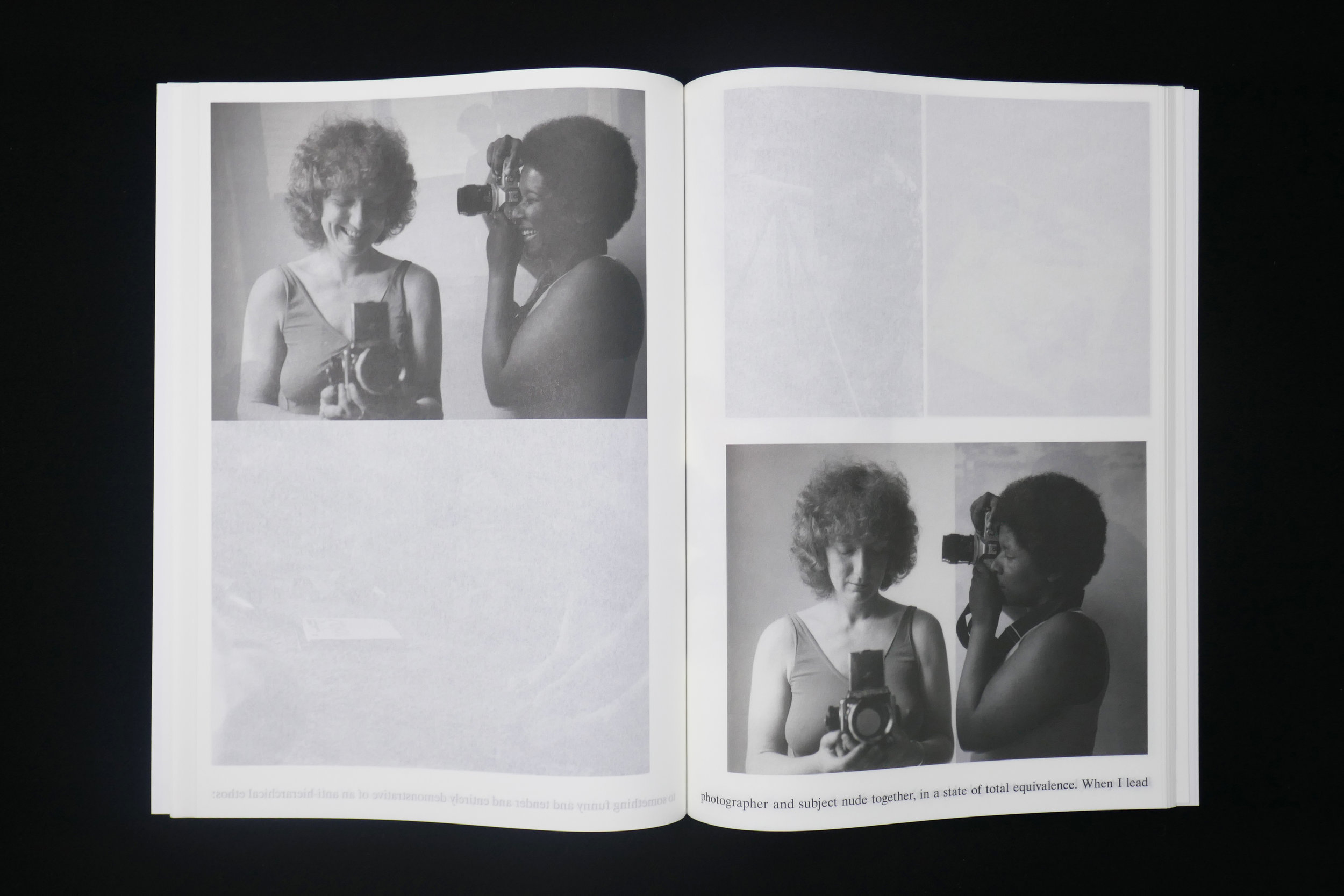

SHVEKA: The use of mirrored walls behind the photographs creates a powerful effect. Can you speak about the decision to include the viewer in the visual field? What did you want to make visitors feel?

HUMERY: The viewer becomes part of the fragmented portrait of Diane Arbus reflected in the mirror. They are not only witnesses to the work, they are also participants in it. Within their field of vision, they see the entirety of her oeuvre without ever fully grasping its boundaries. They themselves become one of the elements of the constellation, just like each of the photographs reflected around them.

In that moment, the line between the image and the viewer disappears. The visitor is no longer separate from the work; they are inside it. And I find that idea poetically very powerful.

SHVEKA: The exhibition deliberately avoids a set path or narrative, creating infinite routes with free guidance. (I encountered several women clutching the show’s notes like a treasure map as they were on a scavenger hunt looking for the artist’s self-portrait or her image of Jayne Mansfield.) What was the intention behind it? Were you afraid to intimidate visitors with this “organized chaos” approach to the design?

HUMERY: I deliberately wanted there to be no fixed path through the exhibition. Each visitor should have their own experience that is unique and unrepeatable. It’s a bit like walking through the city: you never know who you’ll come across, and you’ll never encounter the same people in the same way twice. That sense of unpredictability felt essential.

I also wanted to evoke the wandering, the drifting that Diane Arbus herself experienced as she walked the streets of New York, camera in hand. Maybe at first the layout feels disorienting compared to a traditional exhibition, but I think you quickly adapt. You stop trying to “follow” something, and instead, you begin to look. You begin to discover. And that, to me, feels much closer to the spirit of Arbus’s work.

SHVEKA: What responsibilities do you think a curator holds when deliberately designing disorientation, especially with a body of work that potentially unsettles?

HUMERY: I don’t believe it’s necessarily a curator’s job to offer comfort or clarity. Art isn’t meant to reassure, it’s meant to provoke, to raise questions, to unsettle. If a sense of disorientation leads the viewer to truly see, to slow down, to engage differently, then it’s not a risk, it’s a necessity.

Frankly, I find the idea of protecting the public from discomfort more disturbing than any so-called “destabilizing” artwork. We live in a world that is profoundly disorienting, politically, socially, and emotionally. If an exhibition reflects some of that complexity, it’s not a failure of design. It’s a mirror. So no, I wasn’t afraid of disorienting the viewer. I trusted them. And I believe that this kind of experience can be not only challenging but transformative.

SHVEKA: You’ve highlighted showing the “extra-photographic dimension,” that equilibrium beyond the images. How do you see risk, chance, and exploration coming out from the viewer’s movements around the room?

HUMERY: The relationship between the intra-photographic (what is captured within the frame) and the extra-photographic (what lies outside of it—spatially, socially, temporally) is central to this exhibition. The space is conceived not as a neutral container but as an active field of interaction. The movement of the viewer becomes an extension of the photographic act itself, a continuation of Arbus’s own wanderings.

By eliminating any prescribed path, the exhibition encourages risk: the risk of getting lost, of not understanding, of encountering an image at the “wrong” moment. But it’s precisely through this destabilization that exploration becomes possible. The visitor must engage physically and cognitively, not only looking at the images, but navigating the relations between them, including their own place within that field.

Wim Wenders visited the exhibition and told me he wished he could come back and photograph the visitors themselves, wandering, looking, hesitating. For him, it was like a mise en abyme: the images looking at the people, the people becoming images. And I think he’s right, that dynamic creates a subtle tension, a kind of living echo between the photographs and those who come to see them.

SHVEKA: Was there a moment while going through the images or installing the exhibition that brought up strong emotions or something unexpected?

HUMERY: Yes. I placed each of the 454 photographs myself, physically, alone, directly onto the walls and structures. I didn’t rely on any digital tools, no simulations or previews. Just the images, the space, and time. For three days, I hesitated, adjusted, stepped back, and moved forward again. And then, quite suddenly, everything aligned. As if the images began speaking to one another (or precisely not speaking to one another but speaking to me), without effort. It was as if the exhibition revealed itself. That moment was almost transcendent. Quiet, yet deeply moving. I felt a kind of communion with the work (with her work) that I hadn’t anticipated. To be so immersed in it, to feel it take shape around me, was a rare kind of privilege. A moment outside of time. And as the rhythm of the images settled into place, one after the other, I found myself thinking, quietly, gratefully, of Marvin Israel.

Diane Arbus: Constellation is on view through August 17 at the Park Avenue Armory.