interview by Lara Monro

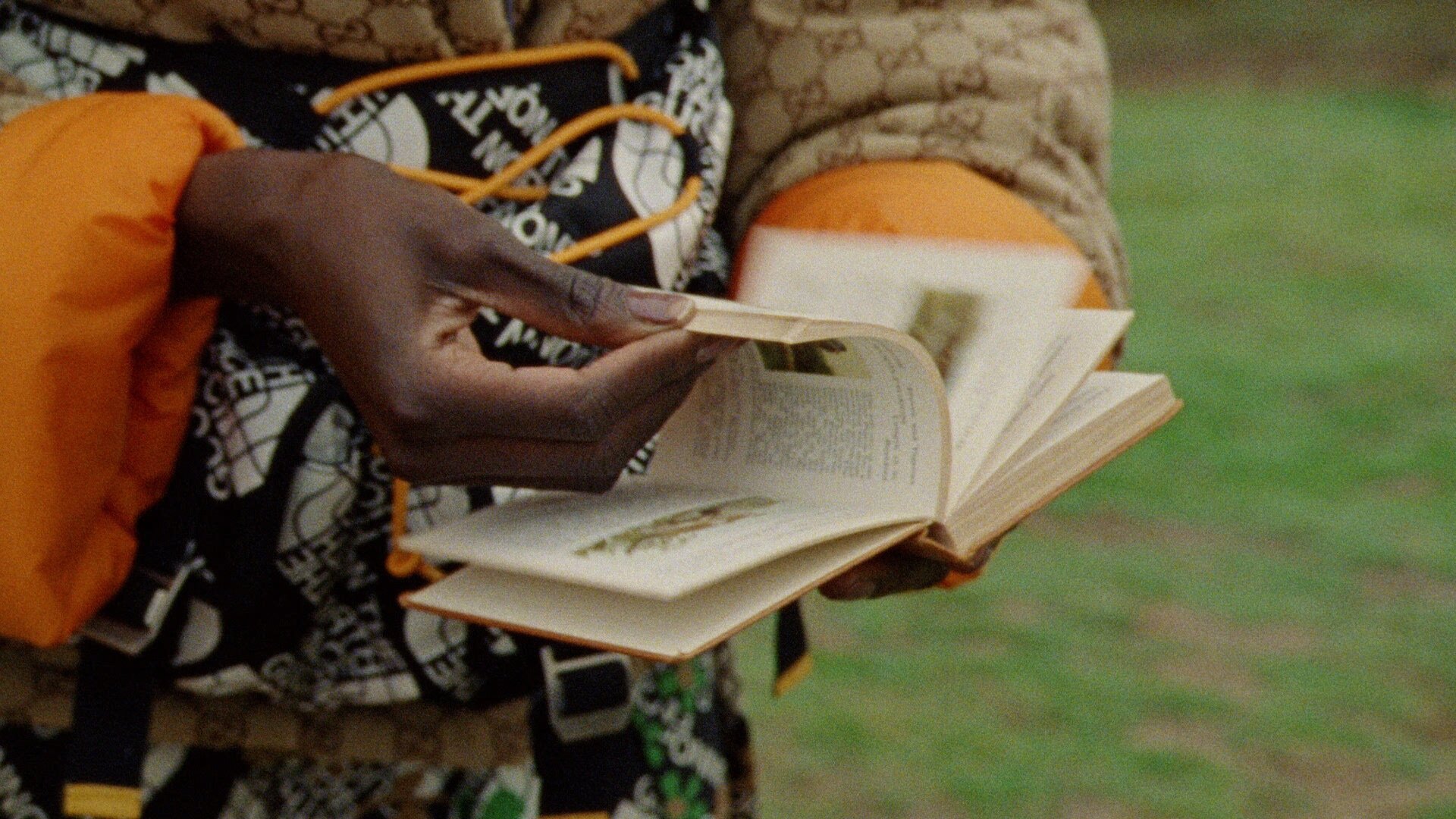

Fiona Jane Burgess, UK-based film director specializing in music videos, commercials, documentaries and fashion films, owes much of her career success to experiencing a number of challenges. Burgess found herself having to rethink her career path at 28, a time when she was also facing the realities of motherhood and the breakup of her band, Woman’s Hour. Fortunately, her natural flare as a director, which she exercised when shooting her own music videos, determined her career segue into film direction. Since delving into the film industry, Burgess has worked on diverse campaigns that span music videos, personal projects, and working with the UK’s No.1 baby feeding brand, Tommee Tippee, as well as some of fashion’s most recognized names, including Gucci and Burberry.

A proud feminist, Burgess is attracted to projects that empower women and provoke debate, amongst many other themes and subjects. COVID-19 highlighted the economic constraints faced by women in the workplace and their predicament of being expected to sacrifice their own economic viability to provide care at home. Burgess recently posted on Instagram around the need to empower working mothers. She spoke passionately to Autre about the response to her recent post, a new film she’s directed for Nowness X AGL, motherhood, and the collective power of sisterhood.

LARA MONRO: It is great to be speaking with you full stop and also timely given the amazing response you have received to your recent Instagram post around women in the workplace and childcare. Did you expect this reaction?

FIONA JANE BURGESS: My mind is blown! I am so humbled by the response. These conversations aren't new, we just so rarely have them openly. For this reason, Instagram can be a powerful platform as it provides the ability to have these sorts of debates, and most importantly, allows others to see them. The burden of childcare on anyone is mammoth. This is bringing to the forefront what it means to be a parent in the film industry, but also the workplace at large. It shows the evident gender inequality that exists and that women are expected to take on the burden of childcare. It is comforting to know what I am saying resonates with so many, but at the same time, deeply frustrating and saddening as so many women feel stuck and trapped. One message that really resonated touched on the creative industry, where for many it isn't just about a financial incentive, but it’s also driven by passion and creative need. When women are forced out of these roles, their mental health suffers as a consequence of not having a creative outlet. This can provoke feelings of guilt, that being a mother isn't good enough. I can fully associate myself with this. I am a mother, but am not first and foremost a mother. It is part of my makeup but it is not my whole, and anyone who wants to simply label me as a mother is missing the point. I have so many different needs. I don't need to just give and receive love from my children. When women become mothers their identity gets put on hold. I disagree with that. How we facilitate mothers in the workplace is an essential, ongoing, question as we work to achieve gender equality.

MONRO: You changed professions at 28, the same year you became a mother to twins and ended up leaving your music career. How did you make the jump into moving image?

BURGESS: When you become a mother, your identity comes into question and everything is focused on the baby. I needed more of a purpose. I was left completely questioning everything after the band broke up as it was so important for me to have my work and role. Around this time a few people asked me to make music videos for them since I had for Woman’s Hour. It made sense for me to do it for the band as it saved money, but I never saw it as a profession! Then, I did it and the penny dropped! It was a really exciting time and everything fell into place. It wasn't easy though. I threw myself into the new industry, but felt so out of my depth. It is such a big industry and I had no connections. I felt alone again in it and all I had was a burning desire and a small seed of self belief—and a very supportive partner. I began my journey. I hadn't pitched before, Suddenly I was sent briefs to pitch on and had to write treatments, which I had also never done. It was a good learning curve but at the same time, after a few months of rejection, I stopped pitching. I realized that I didn't have a crew of people I trusted and wanted to work with. So, I decided to connect with creatives that I did want to work with. It evolved from there. I met a choreographer online and we self-funded a film together. I directed and edited it and this allowed me to get an idea of what my interests were and what I wanted! Personally, my experience of having children was a very traumatizing one, but it also released a crazy energy in me; a desire to have a voice and not shy away from who I am. I was much less willing to compromise on my own happiness. I think this really helped me get to where I wanted to be.

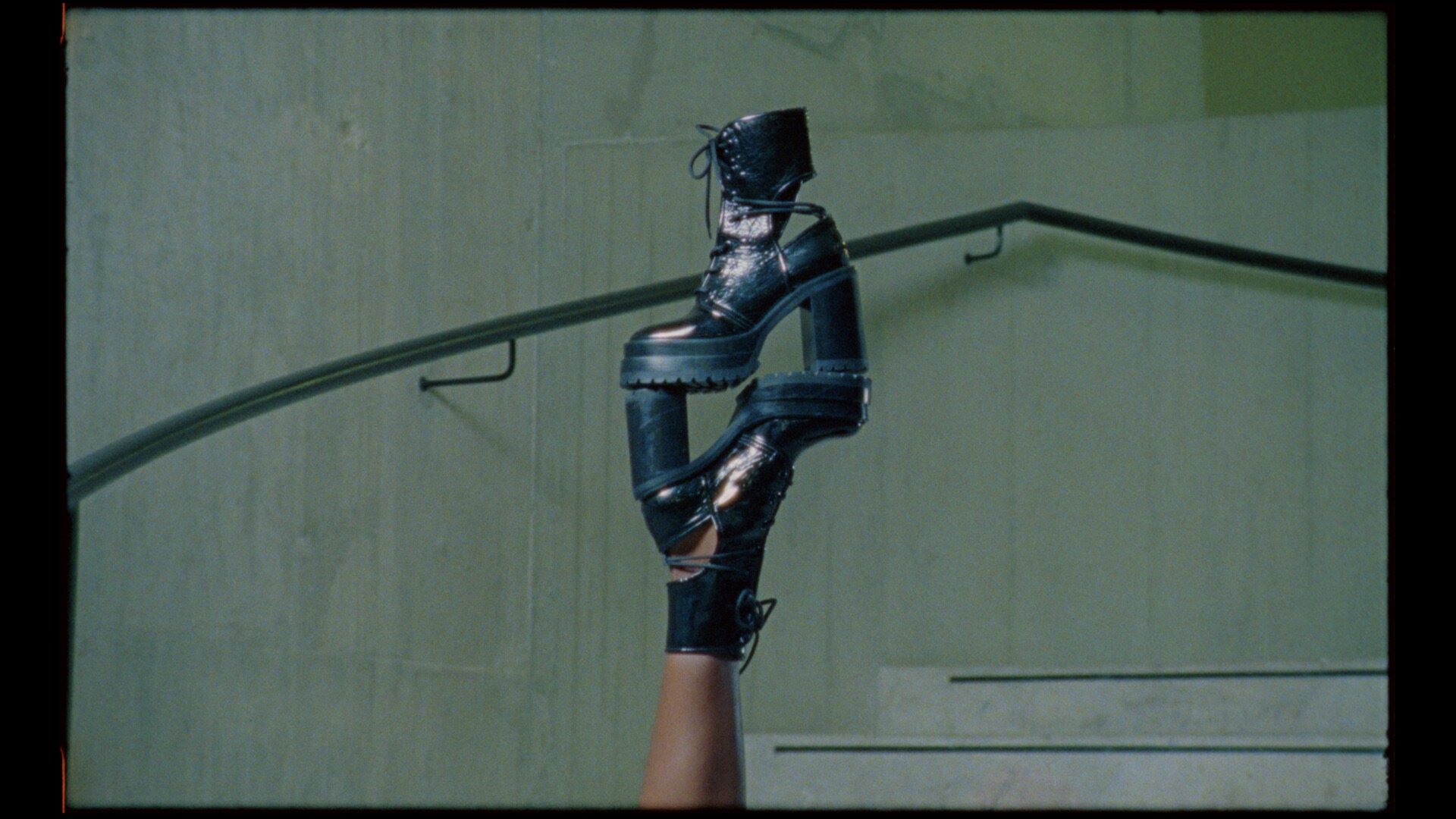

MONRO: You recently directed a short film for Nowness X AGL. It is set within the recognizable, brutalist structure of the Tate Modern and your overarching theme is centered around an anthology of feminist writings from the 1970s Women’s Liberation Movement. Can you tell me more about that?

BURGESS: Yes. The [Feminist] Manifesto was a seminal piece in the feminist movement and allowed women from all walks of life to discuss their own experiences of womanhood; both positive and negative, and what they felt needed to change to create gender equality. There are so many differences between women, to collectively call women one thing is wrong. We aren't first and foremost anything. I don't have sisters (I have 3 brothers!) but in a wider context the sisters I choose—who I am collectively connected to—it felt that the manifesto tied in beautifully with what I was trying to get across through the film.

MONRO: How would you say the film embraces sisterhood?

BURGESS: When I was invited to be part of this it was apparent that my role was not only to facilitate the technical aspect, but also to create a crew and a collective of people who would also input. It felt like the perfect opportunity to call on my sisterhood and embrace the power of our collectivity. I am so often trying to empower and connect with other female creatives, so with this film I ran with that opportunity. I didn't want the theme to be surface level, but part of the process.

MONRO: The singer & songwriter, Lapsley, created a voiceover specifically for the film; can you tell me how this collaboration came about?

BURGESS: I am such a fan of hers. Her album was the soundtrack to my 2020. It includes a number of songs around her experiences of being a woman, so I knew she would be interested in the theme. I sent her the Gloria Steinem quote: “Any woman who chooses to behave like a full human being should be warned that the armies of the status quo will treat her as something of a dirty joke. She will need her sisterhood,” and she came back to me with a beautiful song and very powerful voiceover for the film:

“We run in cycles, chase the morning, pave the way like those before them. It's love and action and its gaining traction This beauty is beyond the surface. She reminds me of my purpose when I feel worthlessness. Its like good love, my sisterhood.”

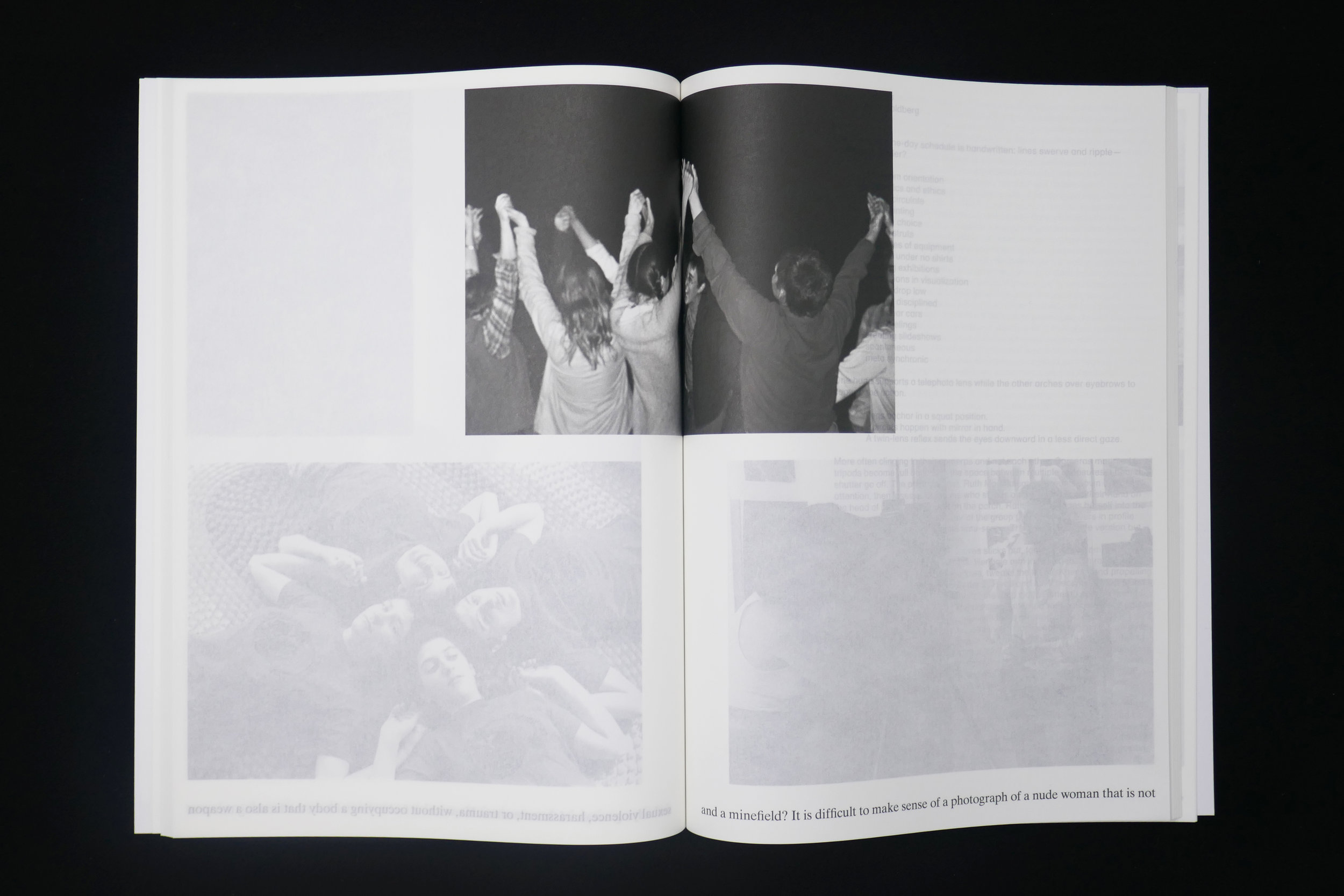

MONRO: You worked with the choreographer Alex Green, referencing the work of 1970s postmodern choreographers Trisha Brown, Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer. Can you say how you incorporated their approach to dance as a visual manifestation of stability and strength through focusing on the subtlety of physical support?

BURGESS: I am very inspired by choreographers from the 1970s. If I could go back to one time it would be 1970s New York! Trisha Brown, Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer were all doing different things, but generally questioning traditional balletic gestures and adopting more everyday gestures. With Trisha Brown, I took a lot of inspiration from her Leaning Duet piece as I often think the simple ideas are the best. This is a great example of that. For me, her choreography pieces are visual manifestations of the simplicity of human support. I wanted to include the three female dancers as AGL was started by three women. And I also wanted to highlight the difficulty of holding a position for a long time, to signify stillness as a symbol for strength. I am interested in creating moments of connection between women that relies on physical balance and support; this idea that if they were to let go they would fall. I also wanted this to show physical manifestations of support structures, of invisible reliance on one another, and to show that—even without knowing—we sometimes rely on the work of others. I think that collective sisterhood is so integral to gender equality as we have a duty and responsibility to hold each other up. To push and challenge one another. In my mind, it's using bodies to embody cultural messages. Distribution of weight is quite difficult: getting the balance right is hard! The simplest things require a lot. Focus and harmony are dependent upon everybody who is involved; giving and receiving the weight, the burden and the responsibility. This is what drew me to this concept.

MONRO: It seems you always bring a personal element to the films you work on. Your recent film for Jo Malone Hope Blooms, for example, shines a light on the charities supported by the brand (Thrive and St Mungo’s) and their horticultural therapy programmes for people who are homeless, or struggling with their mental health in some way. How do you decide on your projects?

BURGESS: Every project is different and has varied requirements, but there has to be a personal and emotional connection. The Jo Malone piece, that was amazing, as on a personal level, I am open about having been in therapy for most of my adult life, and have benefited from being privileged enough to spend that time and energy on myself. I trained in Applied Theatre and worked in a number of community spaces; using art for social change. That is my background and I still host workshops in an adolescent psychiatric unit to support young people who are either in or out patients struggling with mental health issues. My work aims to have a positive interaction that communicates a positive experience.

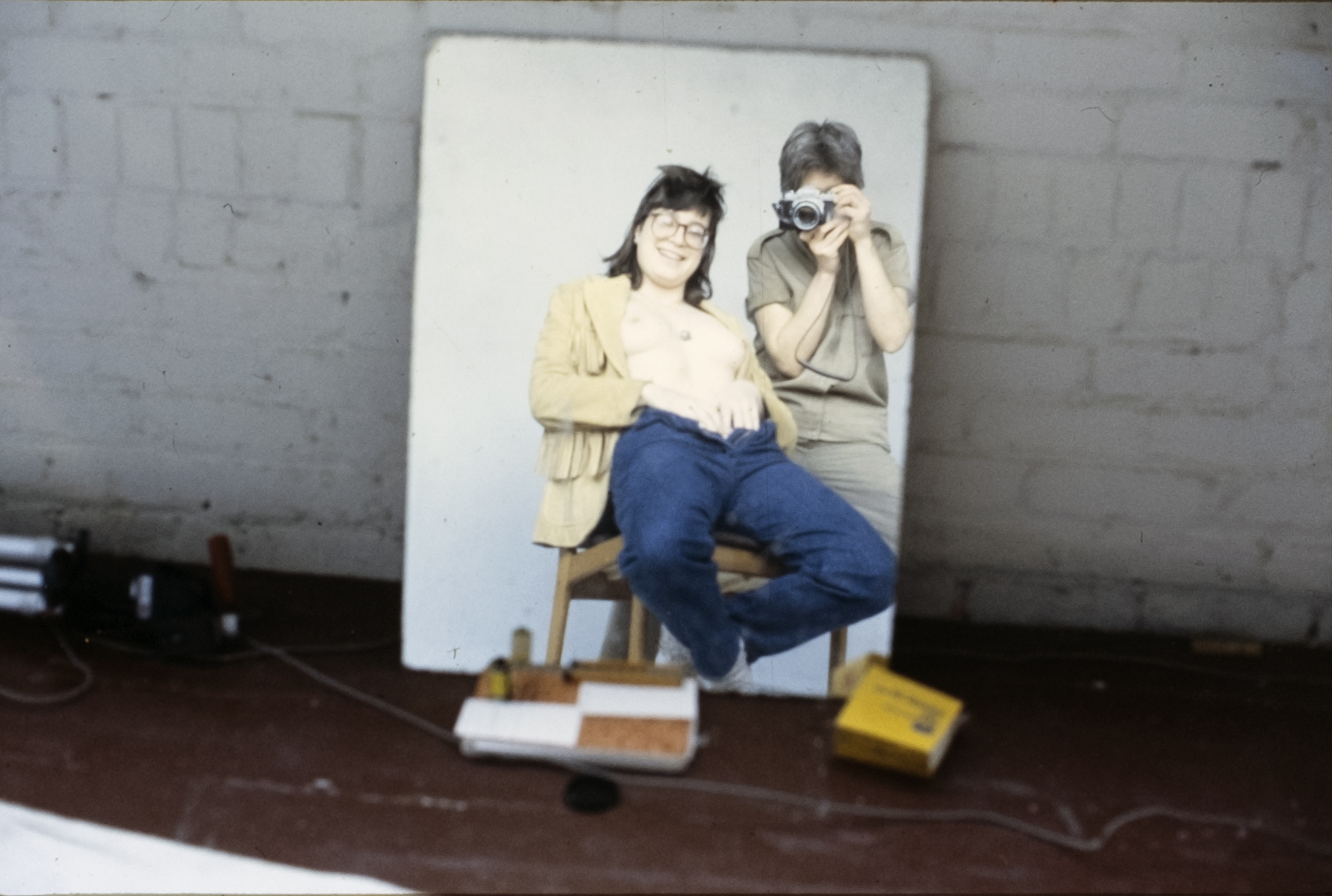

MONRO: A number of your films have been shot in 16mm including High Snobiety X Gucci, Nowness X AGL and Hope Blooms for Jo Malone. What draws you to the medium?

BURGESS: Whenever I can, I shoot on film. I would say I am leaning more and more towards just working with the medium. I am drawn to film’s imperfections, its risks, uncertainty, and spontaneity. Also, there is a tactility to the physical process that excites me. My uncle ran a photographic shop so everyone who needed film developed would go to Quick Snaps. When I was a teenager and learning about cameras—I got an SLR from him and I would take pictures of my friends/landscape—every Saturday I would drop off and pick up a roll of film. That physical exchange and process was special. Respecting the process and the time that goes into it, the physical labor—that is powerful. There is also an element of nostalgia. I will always have that connection to film as part of my history and love of cinema and photography: the physical imagery.