As I first walk into the flagship store for Brendon Babenzien’s Noah brand in the NoLiTa neighborhood of Manhattan, Babenzien is a little on edge. The store, beautiful in its design as it is, still smells of paint and there appears to be a credit card issue (that issue is now completely fixed). So Babenzien politely requests that we take a 15-minute recess and I poke around the store.

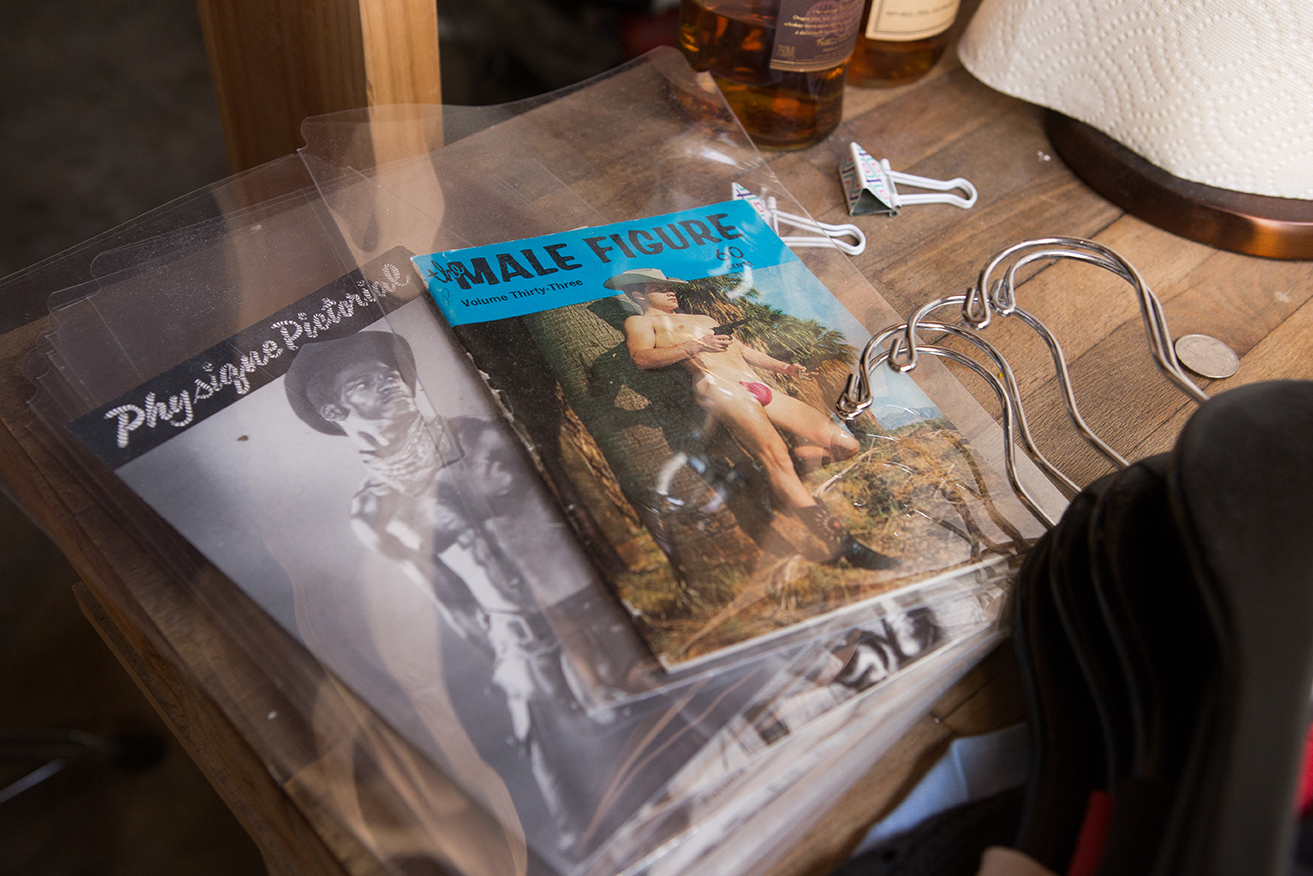

Staying true to the brand’s slight adherence to its beach community theme, the store stands out in the neighborhood full of high fashion boutiques with its white brick exterior and nautical logo on the glass door. Inside is something like a portal to Babenzien’s head. There is an old issue of High Times with John Lydon on the cover, a stack of records, and numerous trinkets and gadgets that would serve a variety of activity-based functions.

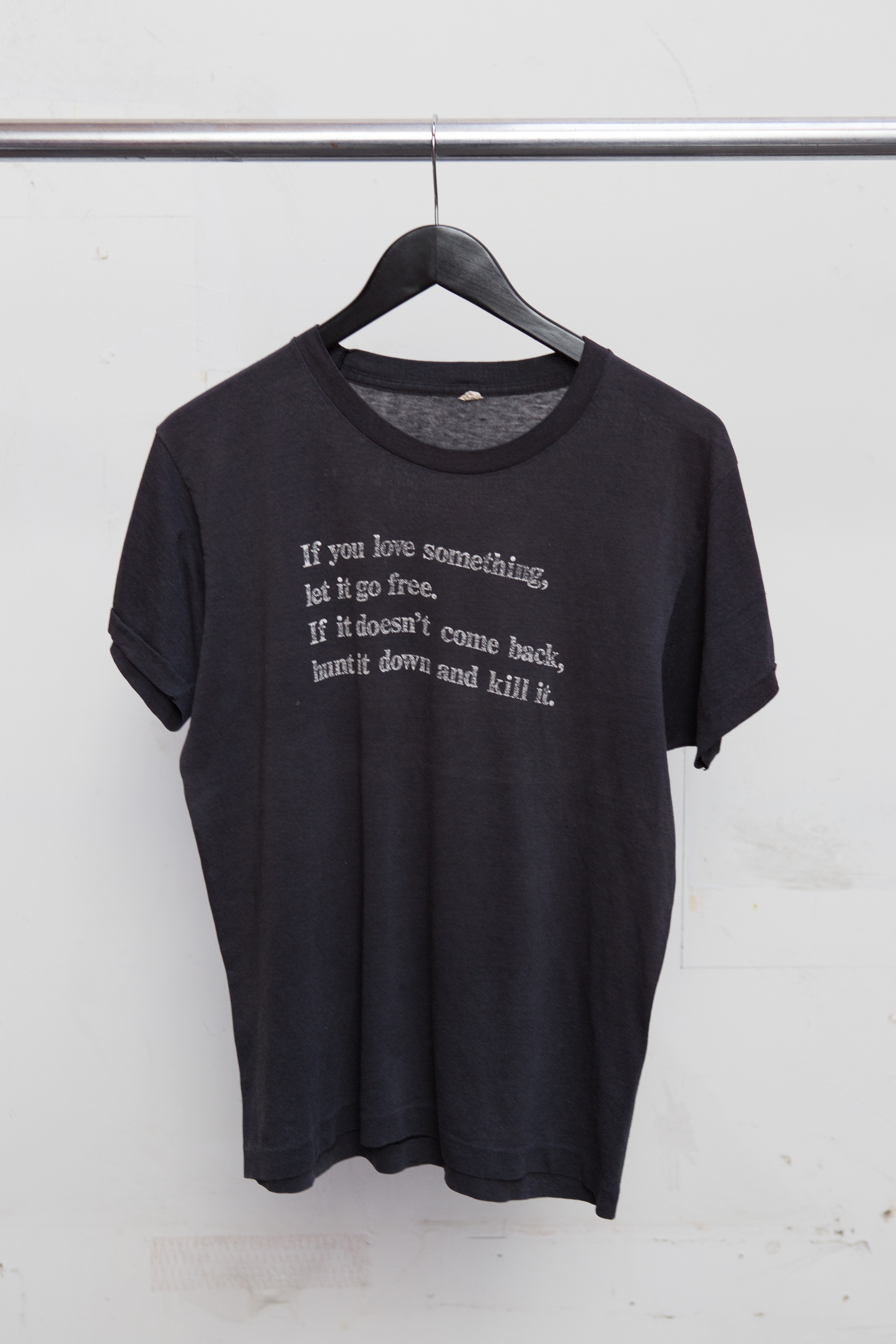

And then of course there are the products. Babenzien has cultivated an aesthetic with Noah; equally informed by beach community prep and skateboarding grunge; but these products have a malleability that could serve a variety of personal styles. They are also high quality and priced exactly in accordance with their qualities. A t-shirt is $48, a sheepskin jacket is $2,000. The whole point of Noah is that the customer is buying a product and not into a brand. Thus, you pay for what you get when you need it.

News launched that Babenzien would be leaving Supreme in February, and Noah was announced shortly thereafter. He is quick to say that he wasn’t unhappy at Supreme, but his daughter had just been born and that instilled in him a drive to start vocalizing his ideas about garment sustainability and smart shopping. Babenzien’s message isn’t all that different than that of say Vivienne Westwood: buy less, buy high quality, buy beautiful.

Babenzien is immediately disarming once conversation gets rolling. He has a mystical surfer guy vibe with a soft cadence to his voice that allows him to deliver philosophies without coming off as too heavy. He and I sat down at the Noah flagship to discuss the brand, sustainability, activity, and how style is everything and fashion is nothing.

Adam Lehrer: I’m really into the whole Noah concept, I grew up on Cape Cod.

Brendon Babenzien: Oh you did, nice!

AL: When I first read an interview about you, you were talking about growing up in a beach community and how that informs the brand.

BB: Did you see the reversal sweatshirt? That literally is from this memory that I had from the clammers working when I was a kid. They’d be out there in the middle of the winter and would be wearing these two-ply sweatshirts. They weren’t even wearing jackets really and they would be digging all winter. My brother would dig for clams just for easy beer money. And my version of that, or what I grew into, was surfing. You share this common experience [living in a beach community]: surfers, fisherman, and people that are just generally beachgoers.

AL: It’s a lifestyle.

BB: You all share this common physical experience: the look of the water, the smell of the water, the beach, the sounds that go with it. I’ve always loved how a surfer and a sailor doing different activities on the same body of water - they share food locations.

AL: There’s like six restaurants, four bars.

BB: I’ve always really loved that overlap. That’s an underlying constant in the brand, but it’s not a nautical brand. It’s one part of the culture. A one-dimensional brand recognizes how you’re going to work. Apple is Apple: it’s clean design. But I think with clothing, that’s influenced by culture, it can be limiting. I’m into a lot of things why can’t I express them all under one roof? If it’s from one voice, it comes off natural. Because we’re small, and the brand is singular, I think it works.

AL: Is that something you were maybe thinking about at the latter days of Supreme, that you wanted to express all the things you love as opposed to a few specific things: art music, skateboarding…

BB: Supreme already does that better than anyone. They throw all these cultures into one place and have it make sense. It wasn’t so much that they’re not doing it so I want to do it. This label is more about me growing up and my personal experiences. There are things that I wanted to say about how I see the world. The only way to do that is to put your own brand out into the culture, and to use your own words. I was only one of many people that went into making Supreme what it is, granted I was an important part of it. But it wasn’t just my voice. It was just time for [Noah], plain and simple.

AL: I’m really interested in how you talk about how the effort put into being fashionable can overrule having style. Does Noah have a specific customer or are you trying to make products that allow people to be who they are?

BB: It’s a really tricky thing. You make all this stuff in a really particular way but then you talk about people being individuals but then you are asking them to step into your box.

AL: (Laughs) Right.

BB: So for lack of a better word, it’s a fucked up situation! That’s one of the reasons that I talk about activities and what they do and what they think because that’s really the thing that gives rise to their personal styles. We’re not asking people to come in and be a “Noah person,” we’re asking them to be themselves and see if any of these products fit their lives. If you want to run in these shorts or you decide this is the year that you’re going to buy a sheepskin jacket, and which one is it? Maybe it’s ours. Maybe it’s the Tom Ford one, I don’t know. But we really like the piece and we hope the customers can do their own things with it. So we aren’t really asking people to join this culture, it’s more how do we intersect with people.

AL: A lot of designers seem to say that they don’t buy into trends, but you’re really a trend averse designer, is that conscious or are you just trying to filter things into the world?

BB: I definitely get nervous with the designer term because I really don’t know if I am. I’m a glorified stylist: I don’t have any design training, and I couldn’t cut a pattern if I tried. I’m something else, but I don’t know what that is yet. The trend-averse thing, it’s not a thought. From the time I was 13 working at a surf shop, I’ve trusted my instincts. Sometimes that leaves you ahead of the curve. We try not to analyze it so much here. I’m not even sure we are trend averse. They are just clothes. But I feel like we sit really closely with the world and I’ve often thought that people that make things, whether it be fashion or television shows, are so closely related in their thinking. I’d love to think that we are ahead of something, but I really don’t think we are.

AL: One thing that I found interesting was that the spectrum of price points is vast, but all the products are priced exactly as they should be. A t-shirt is $45 or a jacket can go up to 2 grand. Is it important to you that the product always matches its price point?

BB: Yes. One of the things at the core of this, from the business side and maybe culturally, we produce garments that make sense and we don’t over-produce. Sometimes the price is really high because you are making a small quantity of a beautiful thing in a very expensive fabric. That is design to me. But a t-shirt shouldn’t be $200, I wouldn’t want to wear a fancy t-shirt. When you have a store, there’s an advantage to things not being ridiculously priced, because you cut out the wholesale component.

[Brendon walks over to the Noah store’s racks of clothing and motions toward a shirt] We have a cashmere shirt, and it’s expensive it’s $800.

AL: I felt it though, it’s nice.

BB: Oh, it’s incredible. If I was in the wholesale department, or I was in another brand that was in a position to buy that fabric, it would be $3,000. That’s a real thing.

AL: And I also think that brands like modern day Saint Laurent selling cut off denim skirts for 1200 dollars just to maintain brand integrity is sick.

BB: I have a hard time critiquing Saint Laurent because of all the “luxury brands” I actually think they are doing a pretty phenomenal job. The clothes are pretty normal.

AL: And that’s interesting because it does go into Yves’s philosophy of normal clothes made in the most luxurious of fabrics.

BB: There’s some stuff where you really see the rock n’ roll influence and maybe there are some people that couldn’t get it, but then they’ll have a coat that by most standards is pretty preppy.

AL: I think it’s more the styling that makes it look subversive.

BB: Yeah it’s incredible. My criticisms of the fashion world mostly have to with it pushing products on the public. Products that people might not be interested in after a year. That has to do with more of my personal consumption. If you buy my jacket you can wear it for 30 years, cool. If you buy something wear it once and throw it in to the back of your closet, we have an issue.

"We live in a fucked up world where there is no perfect answer. So what do I do? I make clothes, I understand brand culture, and I have things that I want people to see. So I open up the doors and communicate every aspect of the process. Focus on how style is style and you need not buy 100 things to look cool."

AL: What’s interesting though is that the people who aren’t smart about shopping buy so much shit, but people like me who do care about a quality product are going to trust you more as the person behind a brand, and they will want to buy Noah.

BB: You would hope. Styling is a huge component. There are things in this room that on one person might look really preppy but on another might look more mod or English punk or whatever. It depends. If I get a 50-year old guy from Naples and he buys this [double breasted jacket] he’s going to look Euro. But someone else could wear it and look like Shane MacGowan. That’s there the style component comes in.

AL: With Supreme, the only thing in front of the brand is the red box logo, has it been weird transitioning to someone who is in front of the brand, doing interviews, in some sense being the face.

BB: Yes (laughs). I’m not a huge fan, but I’m getting more comfortable with it. As a father I feel a responsibility to start communicating these ideas. I’m not good if I’m not taking the little amount of connection I have to people. If I’m not doing that, I’m kind of being irresponsible. If I can maybe open someone’s mind to buying less or starting their own business, then I need to do it. But I don’t necessarily enjoy it.

AL: I just remember when you were at Supreme one video of you came out and everyone was like, “Brendon Babenzien speaks,” it was a big deal, just to hear you speak at all. Now there’s tons of press. It has to be different.

BB: It’s a lot. I’m not stoked. Did you see how stressed I was this morning? It was pretty much because of this. I like talking to you, I like talking to people. All the writers that have come in are informed and cool and it’s a pleasure to have these conversations. But I don’t want to be fucking famous.

AL: And fame can be a by-product.

BB: Here I am trying to talk about consumption issues and buying less and I’m selling products. We live in a fucked up world where there is no perfect answer. So what do I do? I make clothes, I understand brand culture, and I have things that I want people to see. So I open up the doors and communicate every aspect of the process. Focus on how style is style and you need not buy 100 things to look cool. I would argue that people with less money and access that know how to dress are far superior creatively to people that can buy anything they want. It’s easy to buy a Celiné piece and look fresh, Celiné is incredible!

AL: It’s harder to go dig up an old Yohji Yammamoto jacket at a thrift store.

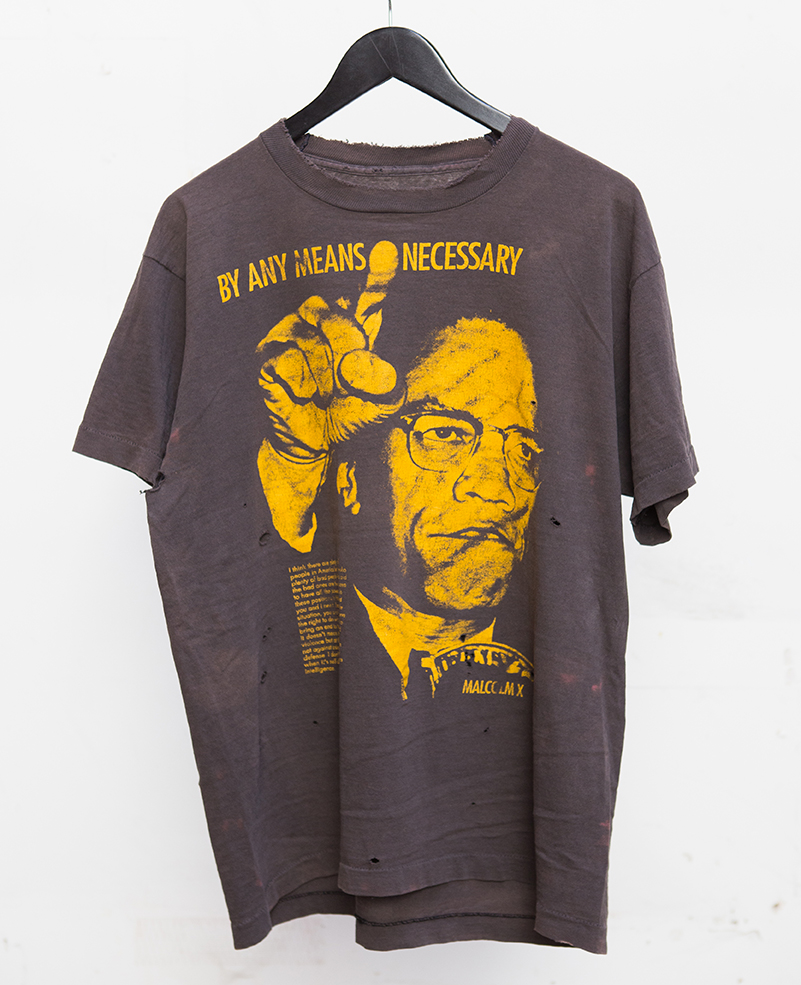

BB: Forget that even. Maybe you can’t even afford that, and you have to co-opt something. That’s why I think skateboard culture and hip-hop culture were so impressive in the early years. These kids had nothing, but they would go buy stuff at Army Navy stores and workwear and make it look fucking cool.

AL: And it’s been influencing everything ever since.

BB: That’s style. To not have to go out and buy the latest and the greatest thing.

AL: You’ve said Supreme was more about the artists, musicians, skaters, surfers, writers, and athletes, are these still your people with Noah?

BB: They’re not even separate. You can’t separate music and fashion and skateboarding and style. Think about skateboarding: the style isn’t just the fashion, it’s the doing. You watch the old Dogtown doc, they say you have to have style. How your arm sits, you land. The clothes are an extension of that. You can say the same thing about a painter or a writer, the physical action of what they do is natural. It’s a style. Because if you skip that process of skating, running, or painting, and go straight to just trying to look a certain way, there’s nothing there. There’s no substance. Shopping shouldn’t be a fucking hobby.

AL: With Supreme something everybody liked were the campaigns with people like Lou Reed, do you still want to use the brand to highlight people that you admire?

BB: Without a doubt. I don’t know that I’m in the position to do that yet, there are costs involved. We’ve already started in some way, these bandanas are from some Japanese kid who cuts up bandanas. We’ll do that, when we can.

AL: To finish up, just sitting here I see people coming in and you seem so interested in people. And stories, and you have ideas and an overall message, do you see yourself in some sense being a storyteller?

BB: I think I like people, I joke a lot that I don’t like people but I just don’t like bad people. I definitely like a good story. I don’t know if I’m the storyteller or if I like other peoples’ stories and want others to know those stories. Maybe I’m the person who spreads the story. Because you realize that there are so many people that do amazing things and don’t get noticed, maybe they don’t have connections, or can’t talk to the press, or don’t understand social media. They never get their due. It’s fucking crazy. Or these days if you aren’t into alternative music or lifestyle, you’re nothing. Why? I met these guys at a wash house the other day. They were these big MMA guys from Maine, like brawlers. And they were there getting some of their clothes washed. They have a big factory in the woods in Maine, and they make MMA fighting gear. And they were super cool, smart, fun to talk to, interested in New York. We talked for like an hour, because they were really interested in fabrics. But if you saw these huge guys walking in and they said, “Yeah I love textiles,” you wouldn’t know how that happened. I love that shit.

The Noah flagship store is now open at 195 Mulberry Street in New York. The online store will be live on October 22, 2015. Text and interview by Adam Lehrer. Images by Thomas Iannaccone. Follow Autre on Instagram: @AUTREMAGAZINE