interview by Adam Lehrer

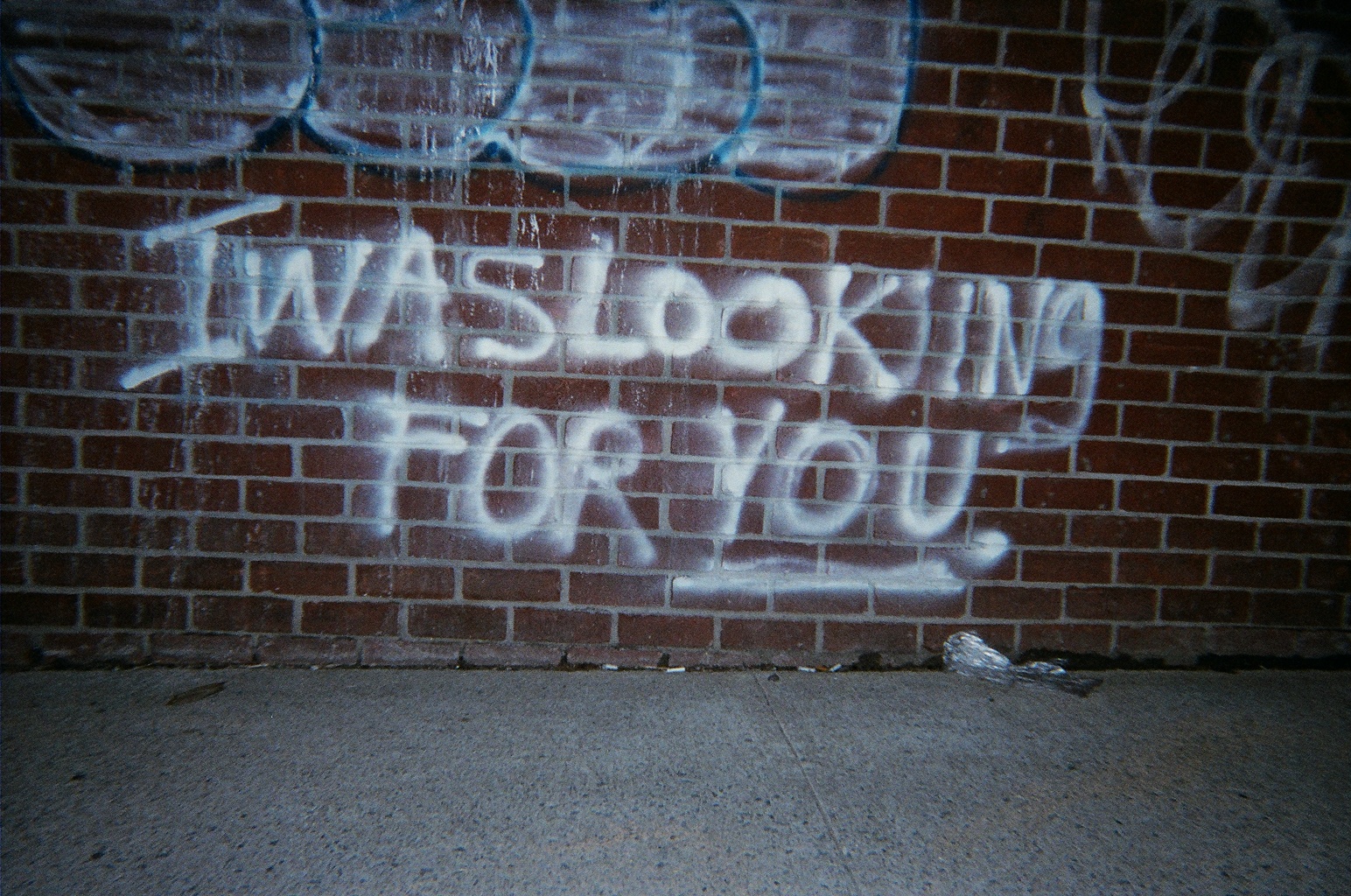

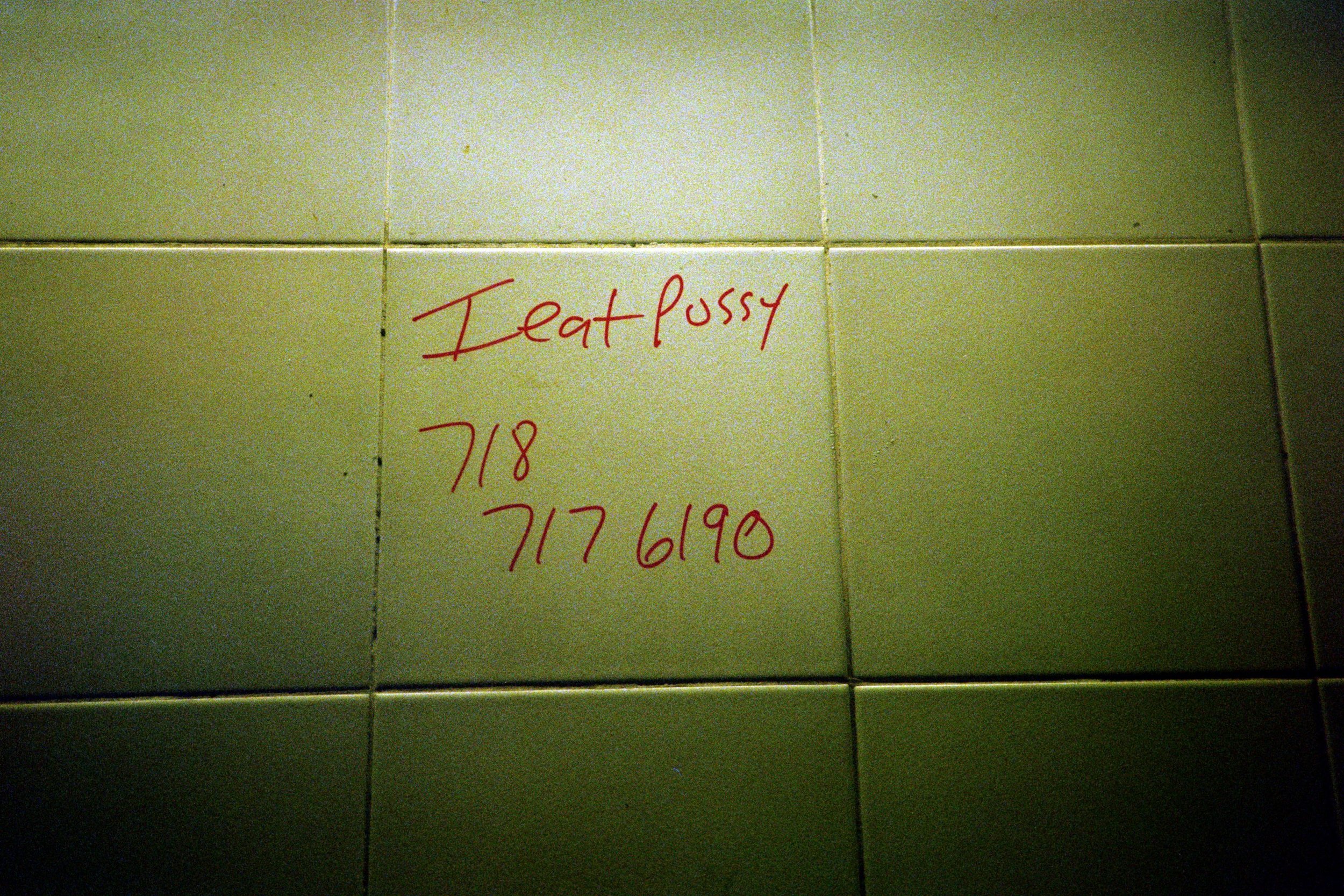

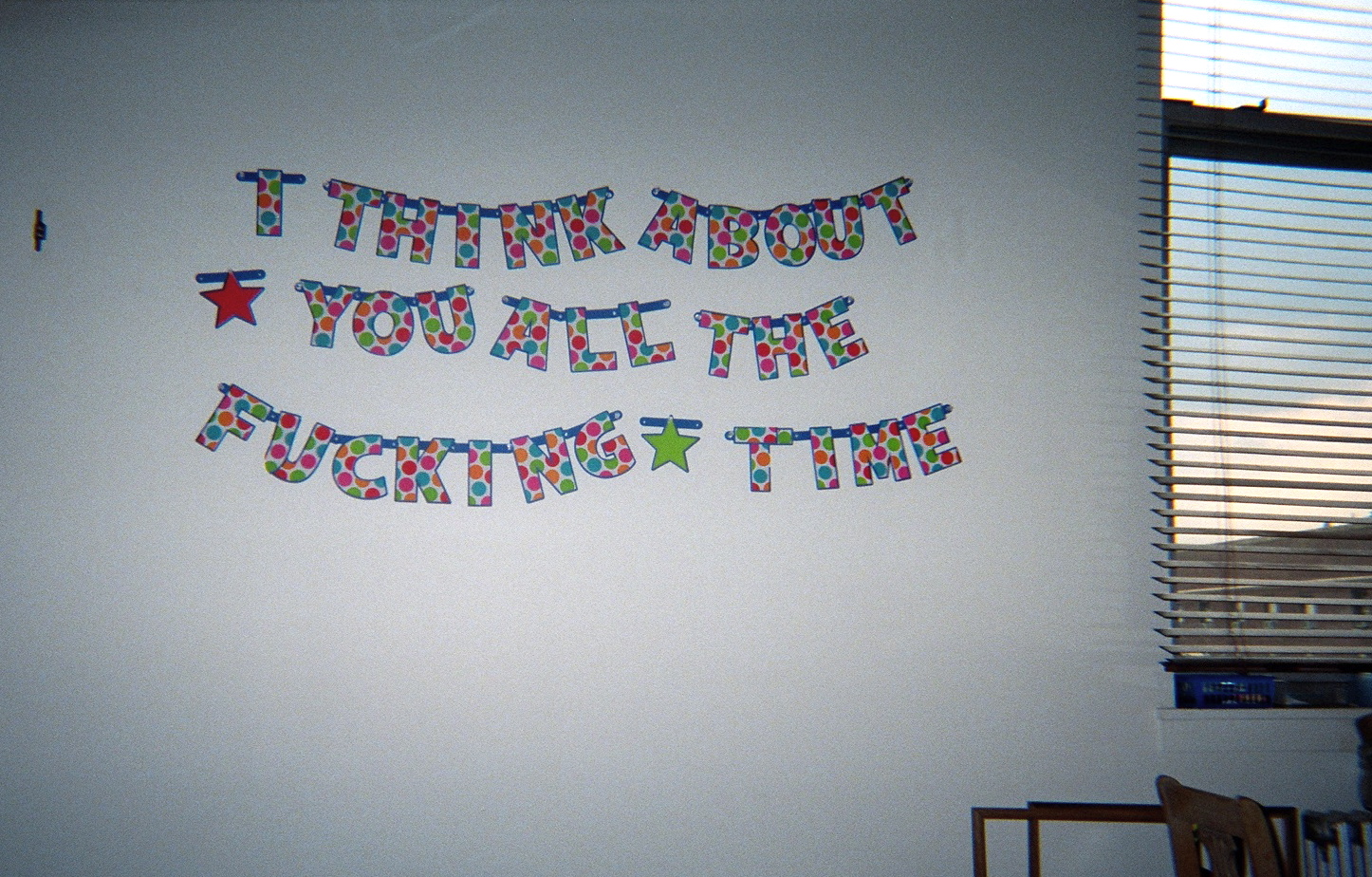

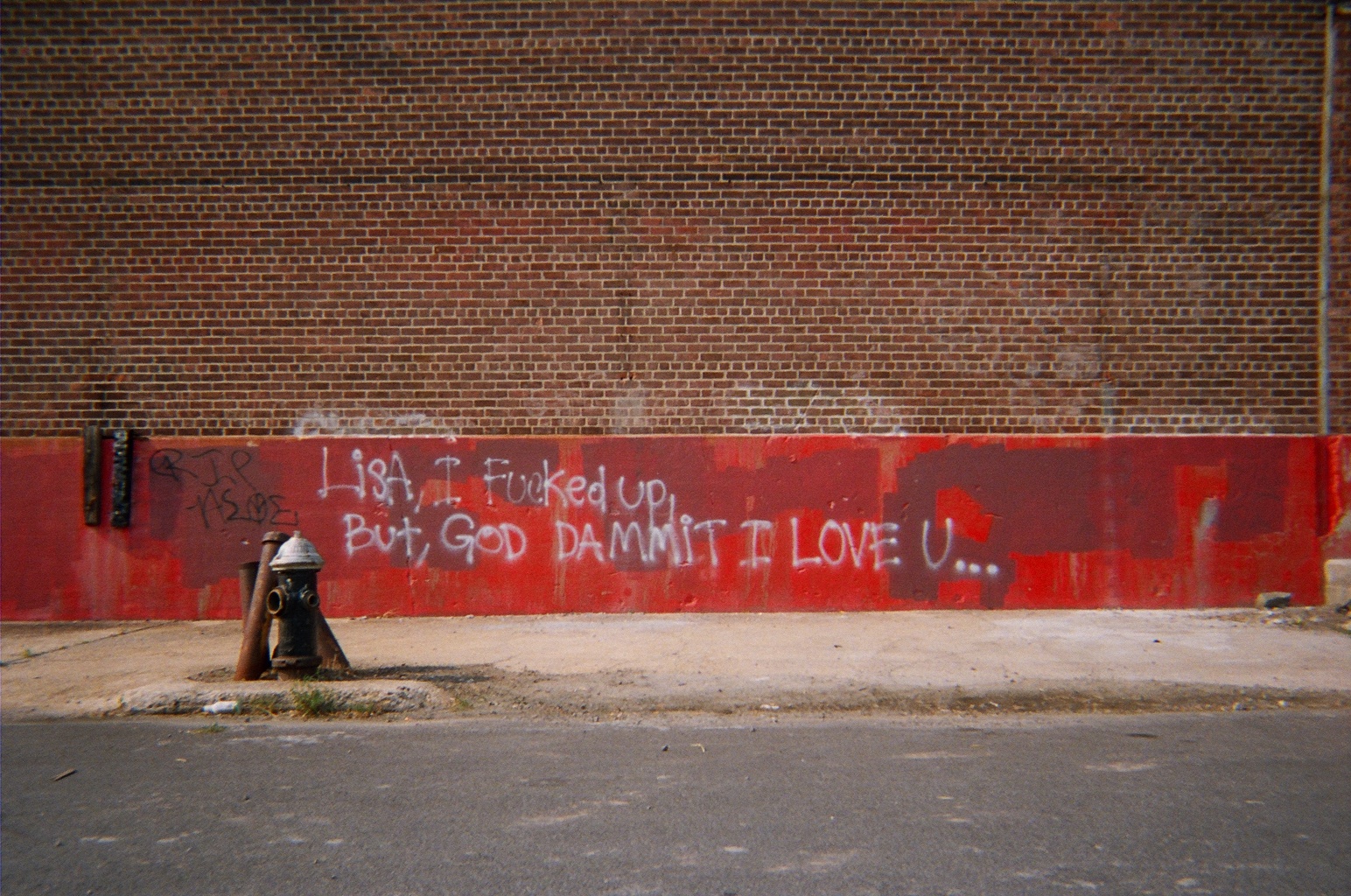

photographs courtesy of Darja Bajagić

Where the political left was once the clear bastion of free speech and expression in the U.S., it could be argued that the new left silences thought and speech perceived as antithetical or offensive to its values almost as much as the right wing does, or did. This is a problem for culture, and evidently, for art. “Political correctness,” says Slovenian philosopher and cultural theorist Slavoj Žižek, “is a desperate attempt by the public norms to tell you what is decent, what is not.” What Žižek suggests here is that political correctness can be harmful in its ability to obscure the truth and dilute public discourse; by sanitizing rhetoric we sanitize cultural meaning. This climate of over-the-top, politically correct theatrics has infiltrated the art world; art’s job is ultimately to push back on societal taboos and interrogate prevailing norms. Good art is almost always offensive to someone.

I first came across Montenegro-born, Chicago-based artist Darja Bajagić at the Independent Art Fair in 2017. Bajagić uses (mostly) monochromatic acrylic painted backgrounds to transform images found within the dark corners of the internet and other non-web sources. Screen-printed atop her canvases are symbols of evil or complex/dual meanings, pornographic images, and pretty girls and boys. Subsequent research reveals these girls and boys to be victims and/or perpetrators of abductions or murders. Bajagić also refuses to over-explain her work, nor does she seek to moralize it (responding to a reporter about her use of a Greek meander motif in recent works was met with Bajagić’s claim that her work is about “the banality of evil”). Her stance has led to her work being misread and mischaracterized. While Bajagić was attending Yale’s Painting and Printmaking program, the Dean suggested she seek professional help. Years later she found herself being censored when her piece Bucharest Molly was removed from an exhibition at Galeria Nicodim.

The cancelation of a duo show between Bajagić and industrial music pioneer, writer, and artist Boyd Rice at Greenspon Gallery reveals the toxicity of political correctness in the art world. Stemming from revelations of numerous events in Rice’s background, such as his usage of fascist imagery in “Non” (an industrial music project), these “revelations” caused an artist-resource listserv entitled “Invisible Dole” to ultimately threaten the gallery’s owner, Amy Greenspon (though it remained installed and was shown privately to those that wanted to see it.) The animus towards Rice was eventually transferred to Darja as well. What they don’t understand about Bajagić is her belief in art’s ability to create conflict, to provoke thought, and to deal with the complexities of the world with nuance and clarity.

If the art world keeps presenting this utopian, groupthink version of the world, art itself is going to collapse. Artists like Darja Bajagić make us look at what we might find ugly, distasteful, and upsetting. I want to be upset. Please offend me. When you offend me, you are forcing me to think for myself. Being offended is healthy. Darja and I corresponded over the Internet to discuss this fiasco as well as her work at large.

ADAM LEHRER: I assume you knew that showing alongside Boyd Rice at Greenspon might ruffle some feathers, but did you anticipate at all that the show would be so offensive to others that it might actually get cancelled?

DARJA BAJAGIĆ: I did not expect any feathers to be ruffled. Only two years ago, in fact, Boyd took part in a group show at Mitchell Algus Gallery. So, I definitely did not foresee the show’s cancellation. The show itself did not cause offense; what generated offense was a series of falsities spread on a “private” listserv by a number of terribly misinformed “art world” persons. As a result of subsequent harassment directed at the gallerist by a select number of those aforementioned persons, including threats to the gallerist’s well-being as well as the gallery’s, the show’s opening was cancelled. Nevertheless, it was installed, and viewable by appointment.

LEHRER: How did you come into contact with Boyd Rice? Had you been a fan of his music and writing? What was it about showing work alongside of him that you thought would be interesting?

BAJAGIĆ: Chris Viaggio, the curator of our two-person, approached me with the idea in January of 2018. It goes without my saying it that Boyd is a pioneering artist. I’ve always appreciated the ambiguousness of his output. Rather than providing any answer(s) to what he re-presents, he functions as a big question mark—forcing the [concerned] individual to answer their own question(s). They must answer it. This modus operandi is now, more than ever, relevant and necessary in the face of the rising, violent insistence to identify and [over-]define to the point of infantilism.

LEHRER: Your work has often been misread and mischaracterized. Are you finding that it’s getting increasingly difficult to show work that is challenging and at the same time not in line with the typical “art friendly” topics of the day, such as identity or inclusivity?

BAJAGIĆ: Yes. First, They Came for the Art. What’s remarkable is that, this time, it’s coming from within [the “art world”]. Artists are fighting to censor other artists. It’s truly absurd. They are executing what they claim to be fighting against, and using Gestapo tactics. Their democracy is, in reality, totalitarianism. They are cowards, essentially. They fear the unknown (we have come back to the violent insistence to identify and [over-]define). What they fail to understand, time after time, is that the subject of art is not the artist. On top of this, it must be acknowledged that, today, the motive of profit outweighs the pursuit of art, in its truest sense. Opportunism is a widespread disease. Complexity is unfashionable, especially if it risks affecting [your] financial stability; an added incentive to degrade [the status of art]—as have we, so has art become reduced. Vapid ornament.

LEHRER: No longer can people seem to grapple with the fact that a depiction is not an endorsement. Obviously, when Pasolini made Salo he wasn’t saying “I like fascism and child abuse,” but he was using the extreme violence as a way to show how power destroys both the victim and victimizer. You, like Pasolini, don’t take a moral stance on the work, which further complicates readings of it. Do you ever fear that if the art world keeps moving in this direction there just won’t be any room for work like yours anymore?

BAJAGIĆ: It is evident that there is a pathetic tendency towards greedy mediocrity. There is an inability or unwillingness to deal in any depth with complexity. Now, when it is needed most, complex systems of aesthetics, or even provocations, are suppressed. That certain things are uncertain or unknown is simply an impossibility and certainly not permissible; you see, Google has all of the answers—as one listserv member wrote, “With one quick google [sic] of Darja and a look at her instagram [sic] I found some pretty questionable stuff.” This included my following the account of Neue Slowenische Kunst on Instagram—clearly they are pitifully unenlightened. They go on to say, “To be clear: I have never met her, have nothing against her and know little about her work. That said, fuck Nazis, White Supremacists and Nationalists. Why is she using this imagery with seemingly no indication that it is not in support of it?”. And there you have it. They admit to knowing “little” about my practice but are nevertheless put-out due to my lack of [an indication of] support towards my artwork’s content, which they are only capable of superficially labeling as “Nazi, White Supremacist(s) and Nationalist(s)” imagery. Symptoms of a myopic perspective. This mania for a sterile, essentially dead, art is detestable. Art should not exist within a zone of safety—this would effectively eliminate its true efficacy and potentiality. Censorship occurs when this true efficacy and potentiality threatens the ruling ideology. What the censors fail to see, however, is that, paradoxically, censorship is like pruning: it gives new strength to what it cuts down.

LEHRER: Your work deals directly with “the banality of evil” as you describe it. What is it about the art world, do you think, that makes it so adverse to this subject matter? Certainly depictions of evil, violence, power, and destruction still exist in cinema (Michael Haneke, Lars von Trier, David Lynch, Catherine Breillat), literature (Brian Evenson, Ryu Murukami, Toni Morrison, Cormac McCarthy), and music (noise music, black metal, even hip hop). And the art world, to outsiders anyways, seems like the most radical of all these industries, but perhaps ironically is the most sterilized in its thematic content. Where is this irony coming from?

BAJAGIĆ: Sterilizing art is a way to defuse its power. Fear and the fear of generating offense is one excuse in the defense of sterilization. Offensiveness is subjective and relative. What a person chooses to be offended by is a matter of personal opinion. Hypersensitivity is a[nother] widespread disease. So widespread has it become that it is now a tyrannical force. Everyone is catching it. And, as the Greenspon cancellation attests to, “even” the “art world” is forfeiting whatever semblance of [its support of] liberty it feigned—bigots and hypocrites, welcome. In regards to depictions of violence, violent images matter. We must force ourselves to see. We are not bloodless. Violent images are not dangerous, but what is is the overwhelming effort to sanitize, delete our access to an unvarnished reality.

LEHRER: You keep a fairly low public profile when compared against the endless self promotion of many artists in the digital age. This has me thinking of “cancel culture,” which I find to be inherently childish and a bit faux, which happens on both sides of the political isle (the left canceling Kanye, the right canceling Nike). By you taking a back seat from self promotion and controlling distribution of your image, are you hoping to at least somewhat emphasize the importance of divorcing your work from your persona?

BAJAGIĆ: For sheeple, innuendo trumps truth. Provincialism is rampant. Even opinions that diverge from those held by [these] mentally incapacitated persons spur onset extinguishing—this is a dangerous intolerance; it, in fact, calls for extinguishing as it eradicates the possibility or potentiality of anything other than itself to exist. Furthermore, yes, it is troubling, the death of the “marketplace of ideas”. Everyone deserves the right to express, discuss, their views. However, we have, instead, in place an obsessive preoccupation with victimhood, and it triggers a furious and compulsive cleansing—a moral panic. And, always, the threat takes on a symbolic form, as in the examples you list. It is an irrational one, as is the subsequent response [of the public]. Society’s hissy fit. As to my emphasizing my art over myself—I find the tendency to focus upon the artist reductive. The subject of art is not the artist. Art is impersonal and external, not in the sense of detachment [between artist and artwork], rather in that it is the process of a truth which is external to the artist but to which the artist is committed. It is addressed to everyone. All interpretations are correct.

LEHRER: You have said that those who get offended by your work are victims of hypersensitivity, but also that you are sympathetic to that hypersensitivity. But also, the work probably wouldn’t be as powerful if it didn’t offend at least some, correct?

BAJAGIĆ: I do not regard my art as offensive. What you are referring to was an answer to a question regarding “negative reactions to the subject matter of [my artworks].” And I followed by saying that What is in fact obscene, offensive, and oppressive is this hypersensitivity, imposing morality. With that said, I am definitely out to make trouble for people who like things to be simple. Because they are not. Things are incredibly complex, subtle, and nuanced.

LEHRER: One thing I am drawn to in your work is that it necessitates engagement beyond one dimensional looking. For instance, if there is an image of a young, pretty girl, the aesthetics of the work might trigger a subtle uneasy feeling but it is only through the extra step of research will the viewer find out that this young girl was the victim of an abduction and only then the art work’s full meaning is attained. Is this a conscious goal of yours, or am I reading too much into it?

BAJAGIĆ: Yes. There is no single definition or “essential nature” of images, and different meanings and use can overlap. The meaning of a word is its use in the language. This is a fact, and it inexhaustibly excites me. Instances of this in my most recent artworks are Beate—helpful, kind, nice, obliging, primitive, subliminally aggressive and vulgar and “German Madeleine McCann,” two paintings that were a part of the Greenspon show. They feature the Greek meander—one of the most important symbols in ancient Greece, and, still today, one of the most common decorative elements. It’s on everything, from architecture to Versace thongs and bikinis designed by Instagram “celebrities,” as well on the flag of the Golden Dawn, a political party in Greece that is ultranationalist and far-right. It is thought to symbolize infinity and unity; to the Golden Dawn, they see it as representing bravery and eternal struggle. So, does this make Versace a supporter of ultranationalist and far-right policies? Of course not. The meaning of a word is its use in the language. However, judging by, say, the logic of the attitudes of the persons who forced the shut-down of the Greenspon show, Versace is unequivocally a supporter of ultranationalist and far-right policies due to their continuous use of the Greek meander in their designs, a symbol now notoriously tied to ultranationalist and far-right policies.

Another instance, in this same body, is Beate Zschäpe in Lonsdale, shrouded in intrigue. In it, Zschäpe is pictured in a Lonsdale top. Lonsdale is a long-running (ca 1960), hugely-popular UK-based brand of sporting clothes. In the late 1990s and through the early 2000s, neo-Nazis co-opted the brand as a means to bypass laws outlawing the public display of Nazi symbols, as by cunningly concealing the first and last two letters with a jacket, only the letters NSDA were left visible, one letter short of NSDAP, the acronym for Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers’ Party). Lonsdale reacted to this trend by marketing initiatives promoting multiculturalism and sponsoring anti-racist campaigns (“Lonsdale Loves All Colours” and “Lonsdale London Against Racism & Hate”). Notwithstanding, the trend (coined Lonsdale youth) was too widespread and took on a life of its own. It was subsequently selectively banned in schools across Germany and the Netherlands. Still, does this make every Lonsdale wearer a neo-Nazi or a member of the NSDAP? Of course not. The meaning of a word is its use in the language. We have to engage with things as they are and not as they appear to us.

LEHRER: One thing I find interesting, if a bit overemphasized, in your work is the critical focus on your use of pornographic images. The porn in the work is usually softcore, especially in comparison with what people see all the time on pornhub and its affiliate sites. But, by divorcing the porn from its source material and placing it into a fine art context, you are able to amplify its meaning to subversive effect. It’s like you are giving an image its power back after that power has been weakened by the sheer amount of images that surround it on the internet. Is this idea something of interest to you?

BAJAGIĆ: Sure. Art prompts the viewer to see and then re-see, and, in this, the power and vitality of the image [in an artwork] is less likely to go unnoticed. It applies to a pornographic image or another—it could be an image of a potato. Reanimating it, in the context of art, often impels suspicious engagement as it recalls its illusionary status. It reminds us that images are not to be taken at face value. They are symbolic constructions, between us and reality. Therein is their power.

NOTE: Neue Slowenische Kunst, or NSK, is a political art collective formed in Slovenia in 1984 that appropriates some fascist symbols into their output, sometimes juxtaposing symbols from totally opposing ideologies, and their musical wing is the successful industrial/avant-garde band Laibach