A Century of The New Yorker by The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library, 2026. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

text and photographs by Isabella Bernabeo

In honor of the iconic magazine’s 100th anniversary, the New York Public Library presents A Century of The New Yorker. Beginning in the light blue wallpaper-covered Rayner Special Collections Wing, visitors are fully immersed in the story of how The New Yorker came to be. High along the walls, the periodical’s most notable covers line the crown molding from end to end.

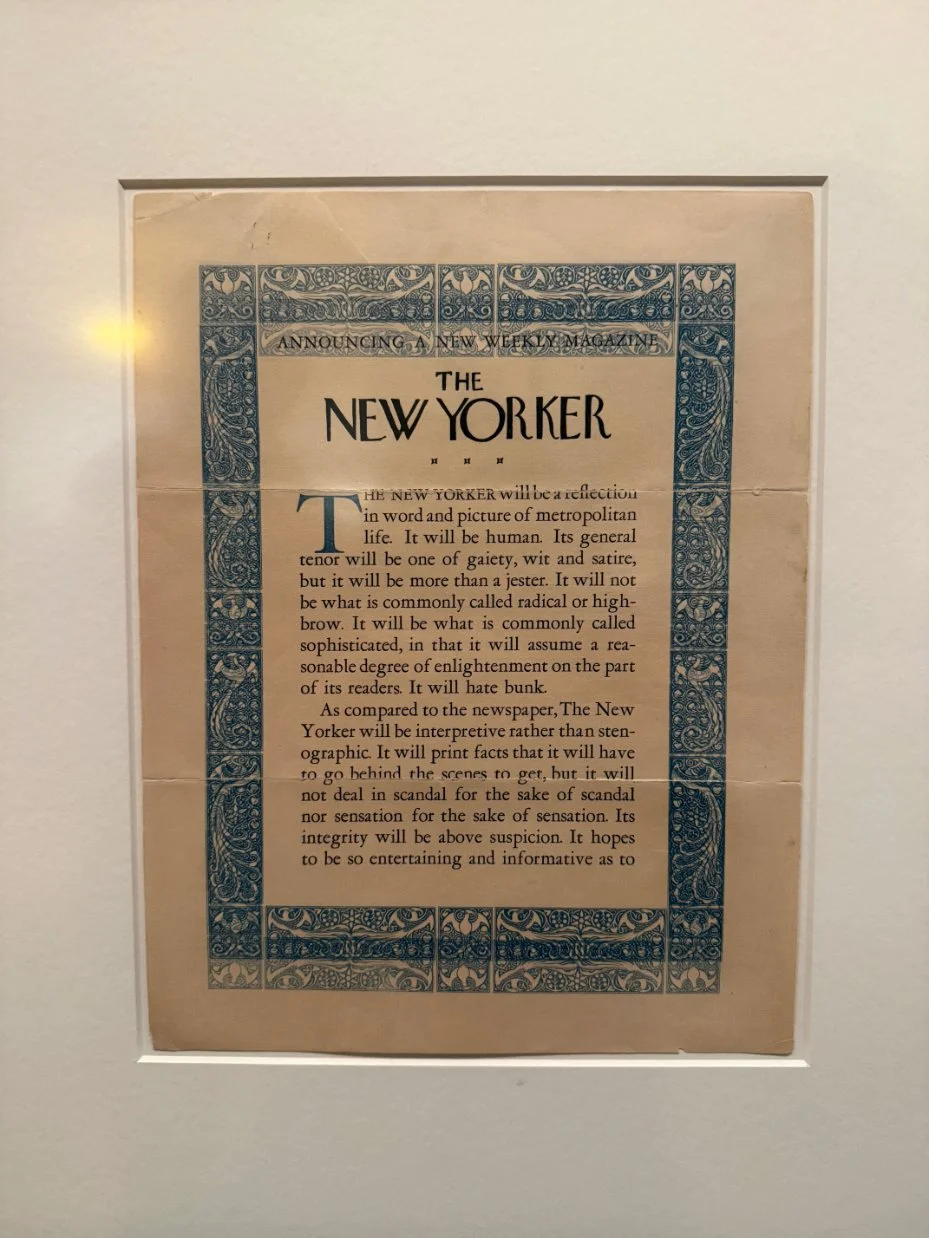

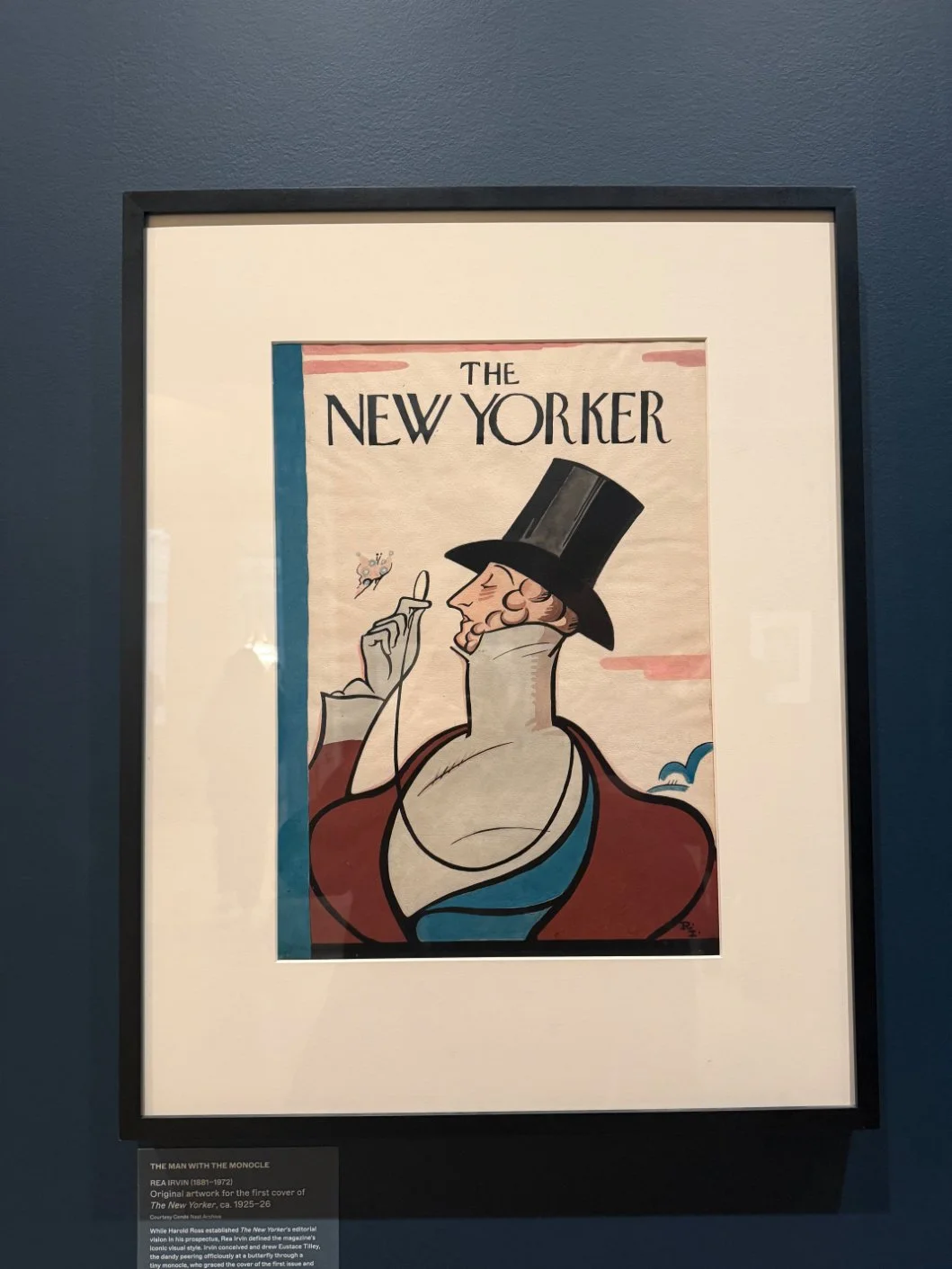

The first section of the exhibit, titled “Beginnings,” opens with the story of husband and wife Harold Ross and Jane Grant launching The New Yorker on February 21, 1925, with the original cover illustration by art editor Rea Irvin—the progenitor of Eustace Tilly aka “The Man with the Monocle.” Through the monocle, Tilly stares at a pink-and-purple butterfly flying about, and with this subtly defiant gesture, a semiotic celebrity was born, thus codifying the magazine’s righteous charge in the pursuit of erudite musings. Here we also see The New Yorker prospectus, written in 1924, where Ross famously declared, “The New Yorker will be the magazine which is not edited for the old lady in Dubuque.” While one might argue this is a hilariously serious sentiment, Ross made his intent to edit a weekly for the unapologetically intellectual.

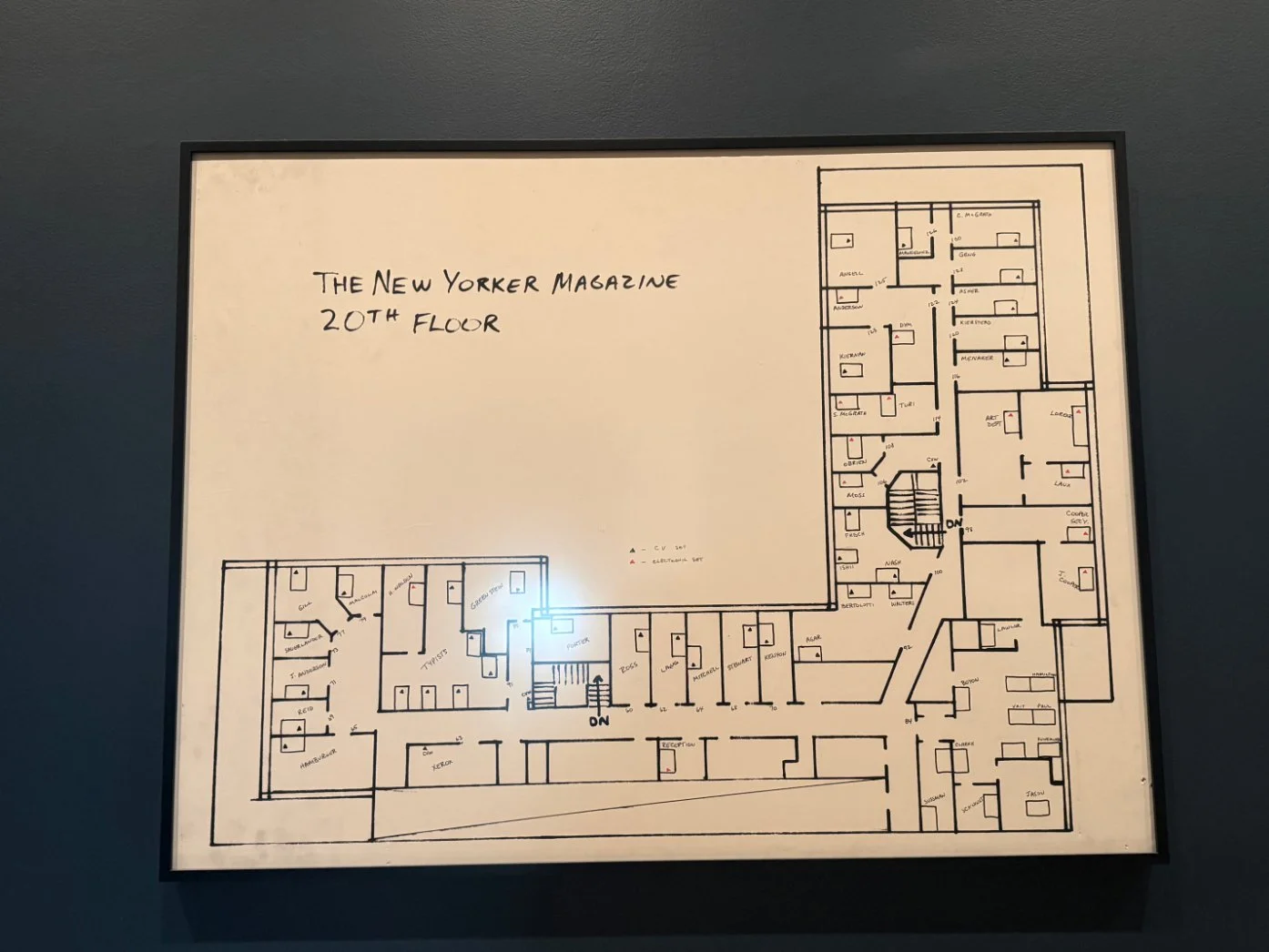

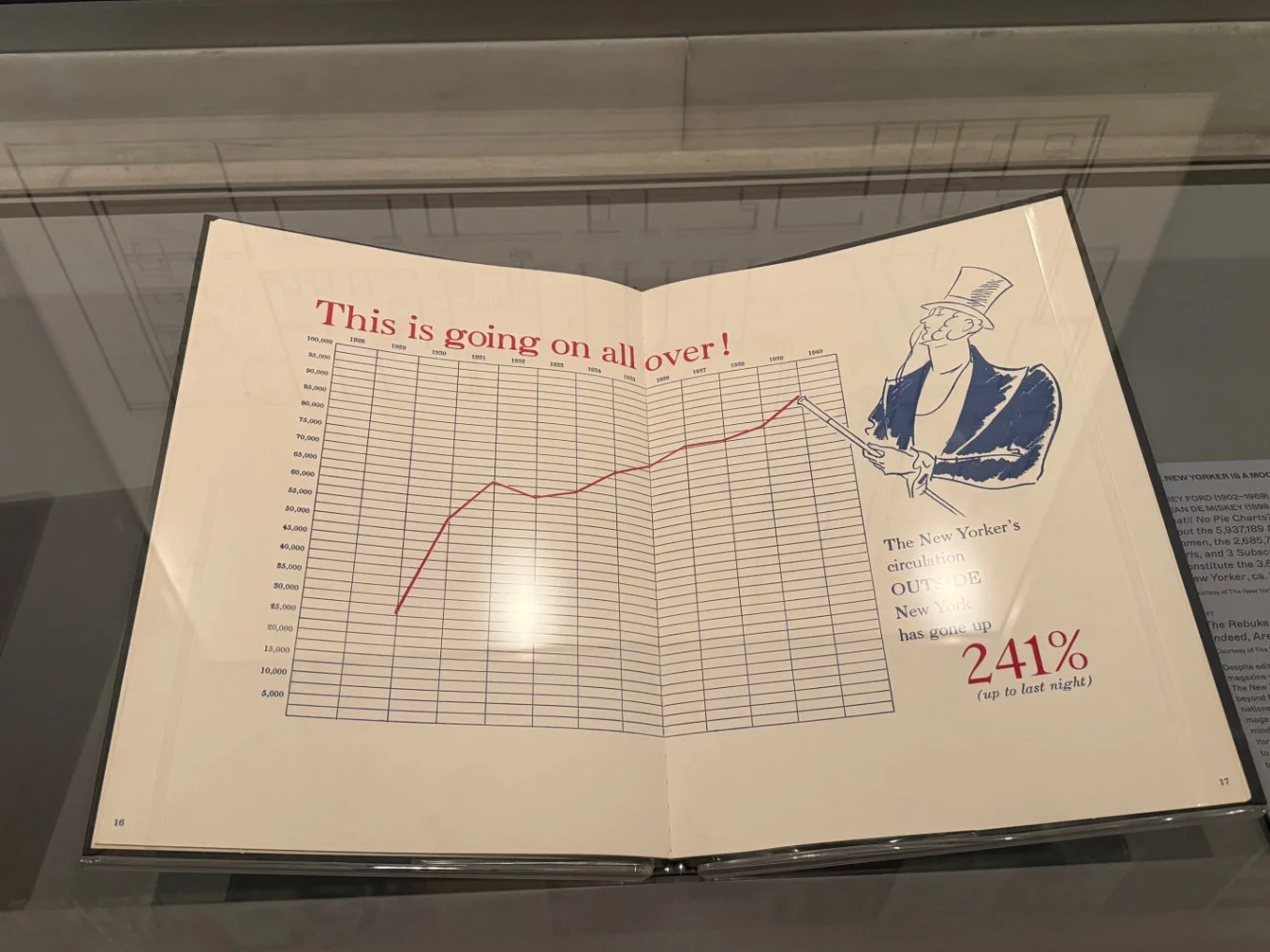

The second section, titled “Anatomy of a Magazine,” features a drawing of The New Yorker’s 20th floor, with names of editors, artists, and more in their respective offices; a remarkably humble team as compared to the current media juggernaut. There are even charts displaying the gradual rise in readership outside of New York from 1930 to 1939, which states, “The New Yorker’s circulation outside New York has gone up 241% (up to last night).”

One of my favorite pieces within this section is from 1927, when the magazine published a profile of the notorious feminist poet Edna St. Vincent Millay that was riddled with errors. Millay’s mother wrote a letter to The New Yorker complaining about the falsehoods, which Ross later published under the title “We Stand Corrected.” Later, in 1970, fact-checker Anne Mortimer-Maddox made a hand-sewn banner featuring Eustace Tilly on the phone with the Latin phrase “Non omnis error stultitia est dicendus,” which translates to “Not every error is folly.” This banner has hung in the fact-checking department ever since, along with a sign that reads “Better perfect than done,” emphasizing their commitment to responsible journalism and correcting their errors.

A Century of The New Yorker by The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library, 2026. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

The third section, “The New Yorker Makes Its Mark,” shares the prolific rise of the magazine during the 1930s and 1940s when they acquired numerous well-known writers and artists as contributors, in addition to its vanguard coverage throughout the Second World War.

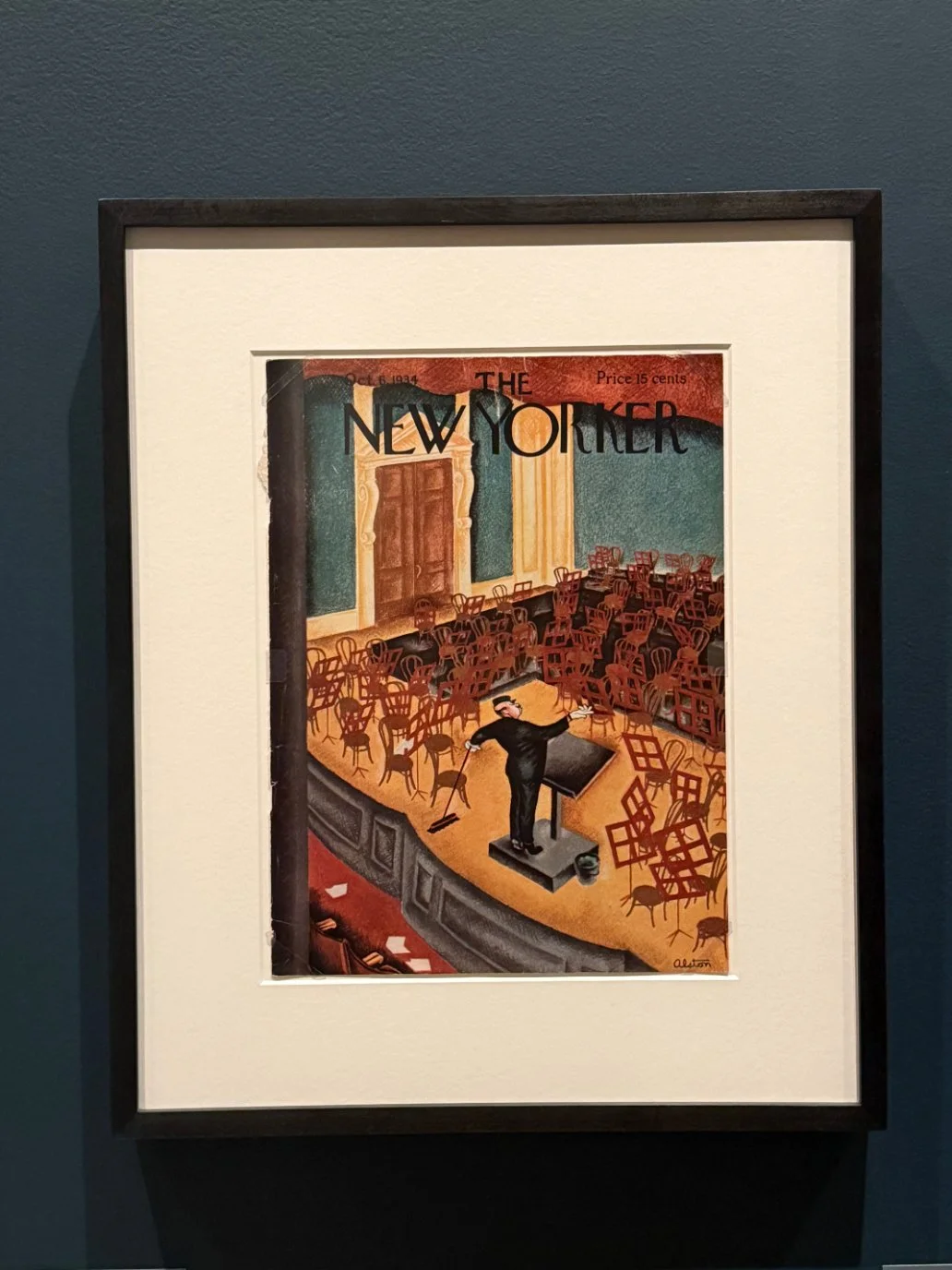

On October 6, 1934, Charles Henry Alston, one of the magazine’s first Black artists to illustrate the cover, drew a janitor conducting an empty orchestra, wielding a mop as his baton. Chairs are thrown everywhere, yet no one else is seen, emphasizing the ubiquity of human ambition, the realization and sharing of which is often only afforded to the privileged few. Alston’s work centered on the Black artists working behind the scenes, who seldom received the credit or fruits of their labor. The New Yorker at this time was mainly made up of a white staff who wrote and drew for white readers; however, this inclusion represented a small stride forward in their stutter-stepping evolution.

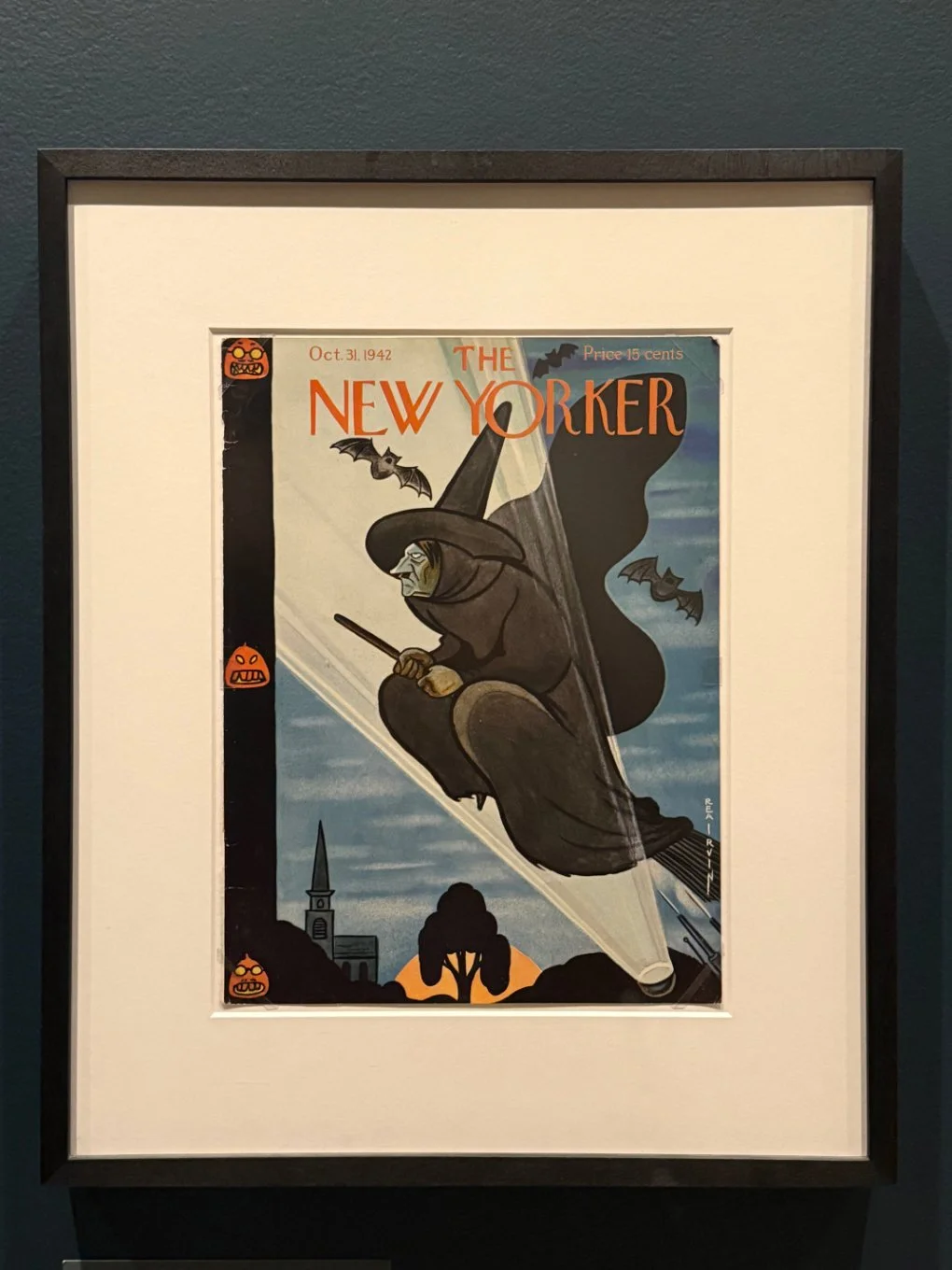

Another notable cover was from The New Yorker’s Halloween edition in 1942. Rea Irvin drew Adolf Hitler as a green-skinned, wicked witch flying in the sky on a broomstick. Ross had typically avoided publishing public figures on the magazine’s cover, however, that was not what made it problematic. The backlash was in response to the three jack-o-lanterns depicted with stereotypically Asian features, othering them as the enemy for siding with the Axis powers. This was also an era rife with racist images of the Japanese that aimed to justify their imprisonment in US internment camps.

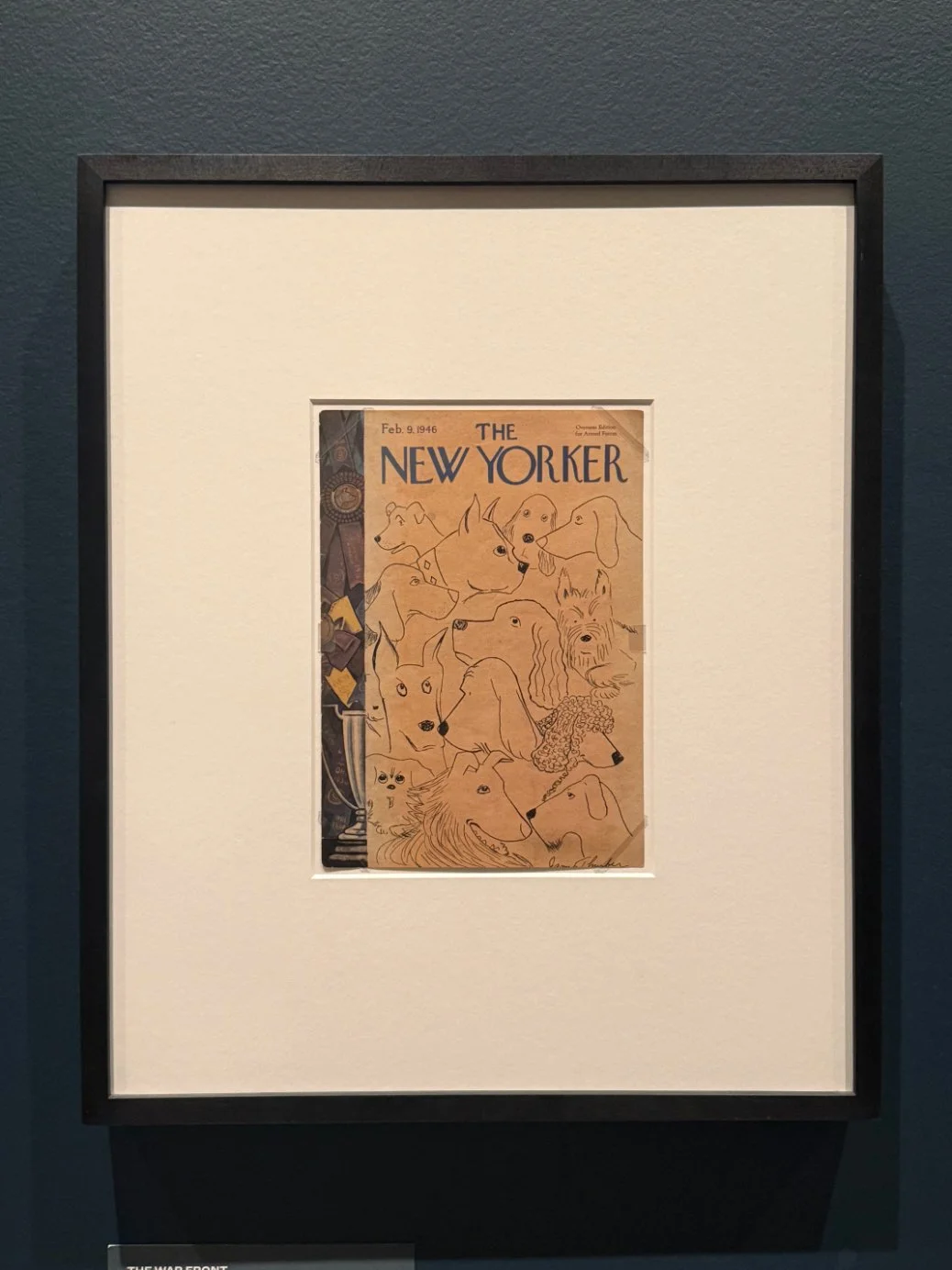

In 1943, The New Yorker began publishing miniature editions of its magazines and sending them overseas for US troops to read. By the end of the war, these miniature editions had circulated more than their standard magazine, leading to their next generation of readership largely belonging to the US military folks.

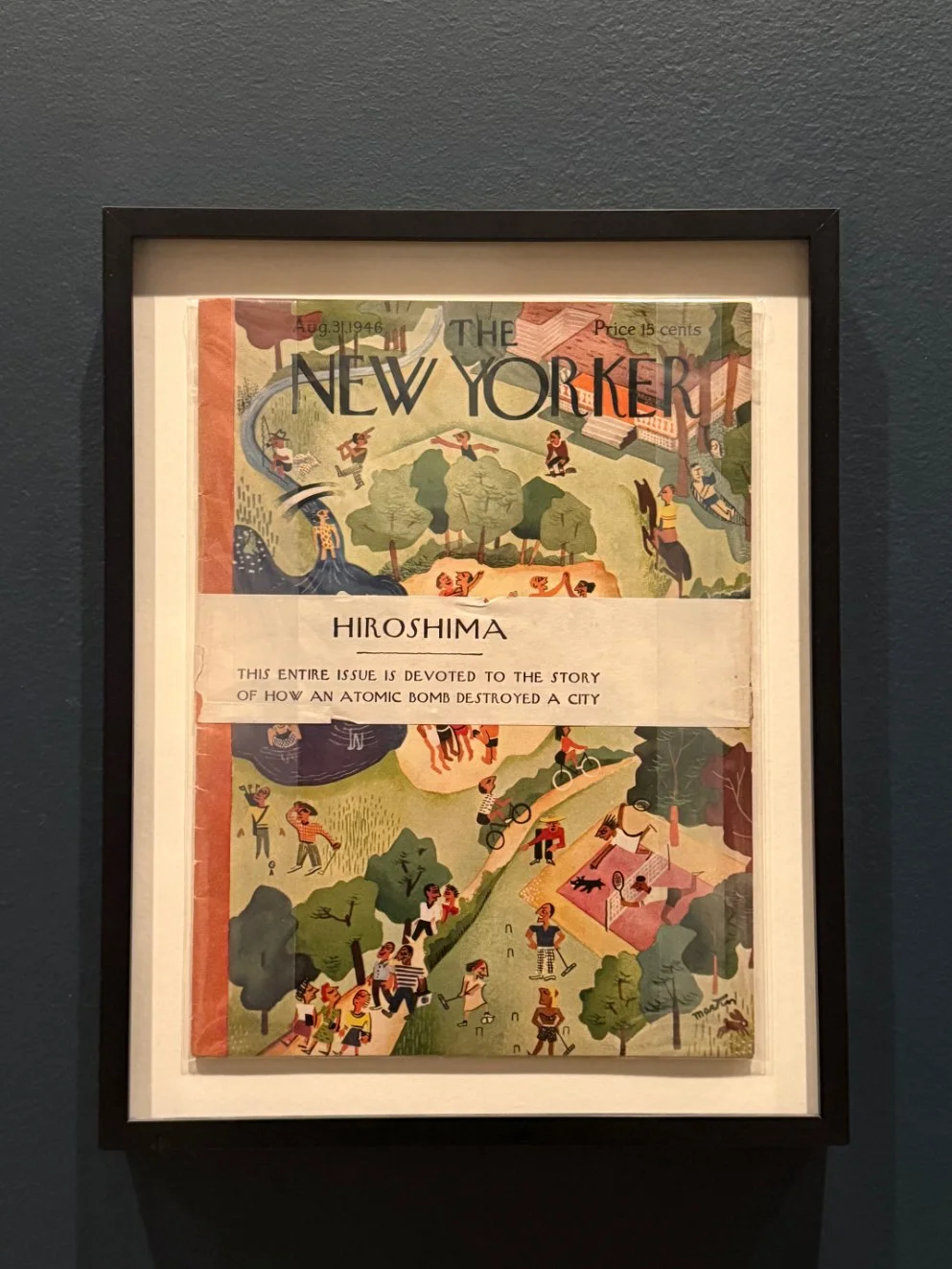

Perhaps the most consequential issue of all time was released on August 31st, 1946, which comprised a single 30,000-word story by war journalist John Hersey detailing the gruesome impact of the atomic bomb on six survivors in Hiroshima. The issue, which sold out within hours, was published with an obi band that stated, “This entire issue is devoted to the story of how an atomic bomb destroyed a city,” however most readers discarded this band, and today, there are almost no known issues that are fully intact.

Continuing across the hall to “The Story of the Century,” the fourth section focuses on Ross’s death in 1951 and on his successor, William Shawn’s, development of a new wave of nonfiction storytelling. One of the most famous issues from this time period was the June 23, 1962, edition, where Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was first serialized before it was later published as a full book. The cover depicted a whale in the ocean with a seagull on its head as an abstraction of ice melting in the background. Carson’s Silent Spring brought to light the dangers that humans have caused to the environment, specifically through the pesticide DDT, leading to the birth of the environmental movement and the establishment of Earth Day in 1970.

A Century of The New Yorker by The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library, 2026. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

The fifth section, titled “A New Era,” details how the global media corporation Advance Publications, Inc. bought The New Yorker in 1985 due to ongoing financial struggles. Chairman S.I. Newhouse promised that the magazine would maintain its editorial independence, but believed it was in desperate need of new leadership to effect a fresh and modernized change, leading to his replacement of William Shawn with esteemed book editor Robert Gottlieb in 1987.

However, this change in leadership was met with strong defiance and backlash from the magazine’s staff, who believed Shawn had been a worthy editor and should carry on. These feelings ran so deep that the magazine staff wrote a letter to Gottlieb urging him to withdraw his acceptance of the position. They signed off the letter with their names, line after line, largely lengthening it and underscoring that he was an unwelcome leader. However, this letter did not change his decision. Gottlieb’s leadership at The New Yorker was brief but effective, as he introduced transparency between departments that had been lacking; however, he failed to keep the staff happy and the magazine evolving.

A Century of The New Yorker by The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library, 2026. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

When Gottlieb left in 1992, he made way for Tina Brown, former editor of Vanity Fair, to modernize The New Yorker. This switch in editors was an extremely radical cultural shift at the time, as her background enabled her to bring more celebrity and pop culture-based news to the magazine, attracting a new set of readers. However, Newhouse disagreed with the approach the magazine was headed in, as he sought for The New Yorker to keep its traditional prestige as compared to the flashier era that Brown brought in. Brown ultimately left The New Yorker in 1998 due to these ongoing tensions, causing Newhouse to appoint the magazine’s current editor, award-winning journalist David Remnick who has expanded the magazine into its current multimedia era and allowed subscriptions to keep their finances high instead of their previous ad-dependent approach, leading into the sixth and final section of the exhibit, titled “The 21st-Century New Yorker.”

The internet caused great concern for The New Yorker, as it did for many other publications, over how they would survive in the online world. However, this new era also led the way for the publication to further diversify its staff and publish works on important political topics.

A Century of The New Yorker by The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library, 2026. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

Viewers get an inside look at the evolving office space where the magazine is made. The office moved in 2015 from 20 West 43rd Street to One World Trade Center and has become much more lively in an effort to mature from a simple workspace to a true community. People dash around the open floor plan to meet with other departments, and there are now spaces to relax, eat, and take breaks, fostering a much healthier community than that of the 20th century.

A Century of The New Yorker by The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library, 2026. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

Another flashback is a riff from Irvin’s first cover made on March 6, 2017, by artist Barry Blitt. It features Vladimir Putin as Eustace Tilly, looking through his monocle at a butterfly with Donald Trump’s face and the logo spelled out in Russian. A clear indication that Remnick has no qualms with placing public figures on covers. If World War II has taught us anything, it’s that American foreign policy is not an issue that the media can afford to ignore.

However, Eustace Tilly, redrawn as Putin, is one of many symbols that The Man with the Monocle has come to represent. Since its inception, The New Yorker has used Eustace Tilly to embody numerous ethnicities and genders. It has grown into a magazine where writers and artists of all ages and identities are invited to contribute to unabashedly studious discourse without regard for being perceived as pretentious or pedantic.

A Century of The New Yorker by The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library, 2026. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

The exhibit is free and available for viewing through February 2 @ the Stephan A. Schwarzman Building, 476 5th Ave.