text by Emma Grimes

Visiting David Zwirner’s new Dan Flavin exhibit feels more like exploring an incandescent expanse than walking through a gallery. Every room contains just one or two of his fluorescent installations, giving each of them the space to settle and saturate the ceiling and walls. The ongoing exhibition focuses on Flavin’s grid pieces, which are a denser and more complex development of the spare, one or two-bulbed installations that first brought the artist to recognition.

Flavin called his works “situations,” a term that underscores their interdependence with space and context. The word also hints at their delicacy: the light bulbs can always be switched off, the lamps replaced. What matters is not the bulbs themselves, but your experience encountering them: the bulbs of colors radiating off the grids, suffusing the white walls, and one’s own body drifting through the space.

The first room holds the artist’s 1987 untitled (in honor of Leo at the 30th anniversary of his gallery) — one of many pieces dedicated to his longtime dealer, Leo Castelli. Three identical, five-by-five grids adjoin, and each horizontal lamp glows in one shade of the rainbow. On the floor below, the images reflect on the concrete, radiating in an ombre duplicate.

As you walk closer to the structure, the reflection on the floor recedes. As you retreat, the ombre reemerges. The grids themselves are not changing, of course, but your image of them does. Perception reveals itself to be—to use Flavin’s word—situational.

Behind the installation, a purple-pink light bathes the wall. Flavin has been described as a painter because of the way his installations color everything near. But painting feels slightly too vague and inexact as an analogy. The light is soft and diffuse. The neon grids light the walls, saturating them in radiant pastel shades so definitively that they erase the boundary between artwork and space.

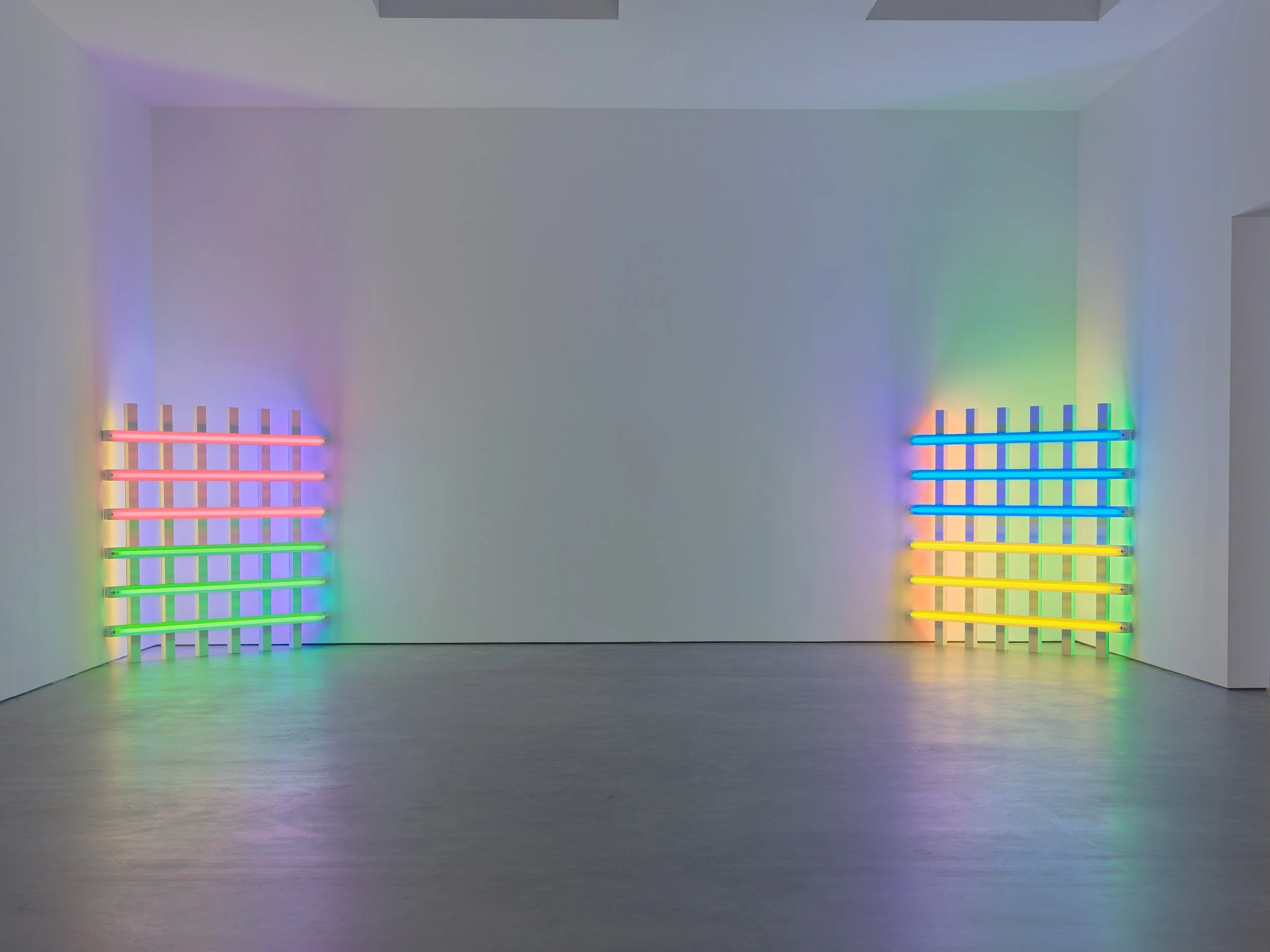

In the following room, two grids appear in adjacent corners with opposing color schemes. One is pink and green; the other is blue and yellow. Each reflects the opposite color combination on the wall behind (the pink/green one has a blue/yellow reflection, and vice versa). Whereas in the previous work, you encounter the effect of the light and its source simultaneously, here you first encounter the effect, and only upon walking up close to the grid can you notice that there are lightbulbs on the backside, responsible for the reflection.