For any connoisseur of Japanese art, the ambiguous phenomena that have characterized Izumi Kato's work for more than two decades may seem familiar. Yet there is never any complete correspondence, only omnipresent echoes, the distinctive signs of a highly singular artistic universe.

Since the 2000s, Kato’s "untitled" sculptures, paintings, and drawings have featured hybrid figures (their limbs and breath producing vegetal or human shoots), budding flowers (often lotuses, the Buddhist flower par excellence, a symbol of purifying transformation plunging its roots into the mud), and other beings (human heads or homunculi hanging from bodies like clusters of ganglia). In the latter case, the multiplication is truly “monstrous;” the lotuses don’t proliferate. But they spring from an exhalation that evokes another type of Japanese art, the He-Gassen emaki (literally "fart scroll"), some of which show yokai fighting in a mad battle of winds (like the "Shinnô scroll" in the Hyôgo History Museum). The strange small creatures that spring up like ganglia from the larger figures also recall battles against monstrous animals, like the heroic struggle against the giant tarantula Tsuchi-gumo, at the end of which thousands of human skulls emerge from the spider’s severed neck. The play of mirrors between Kato's work and Japanese art creates limitless perspectives.

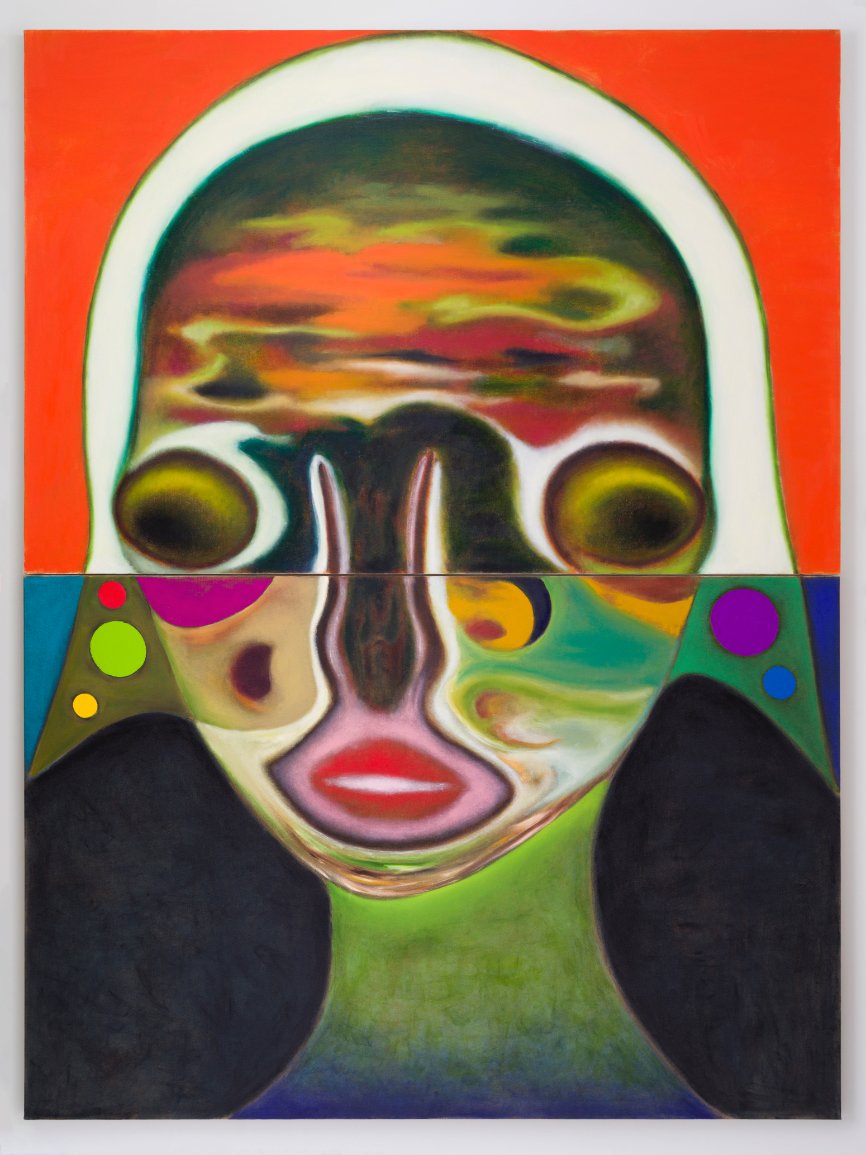

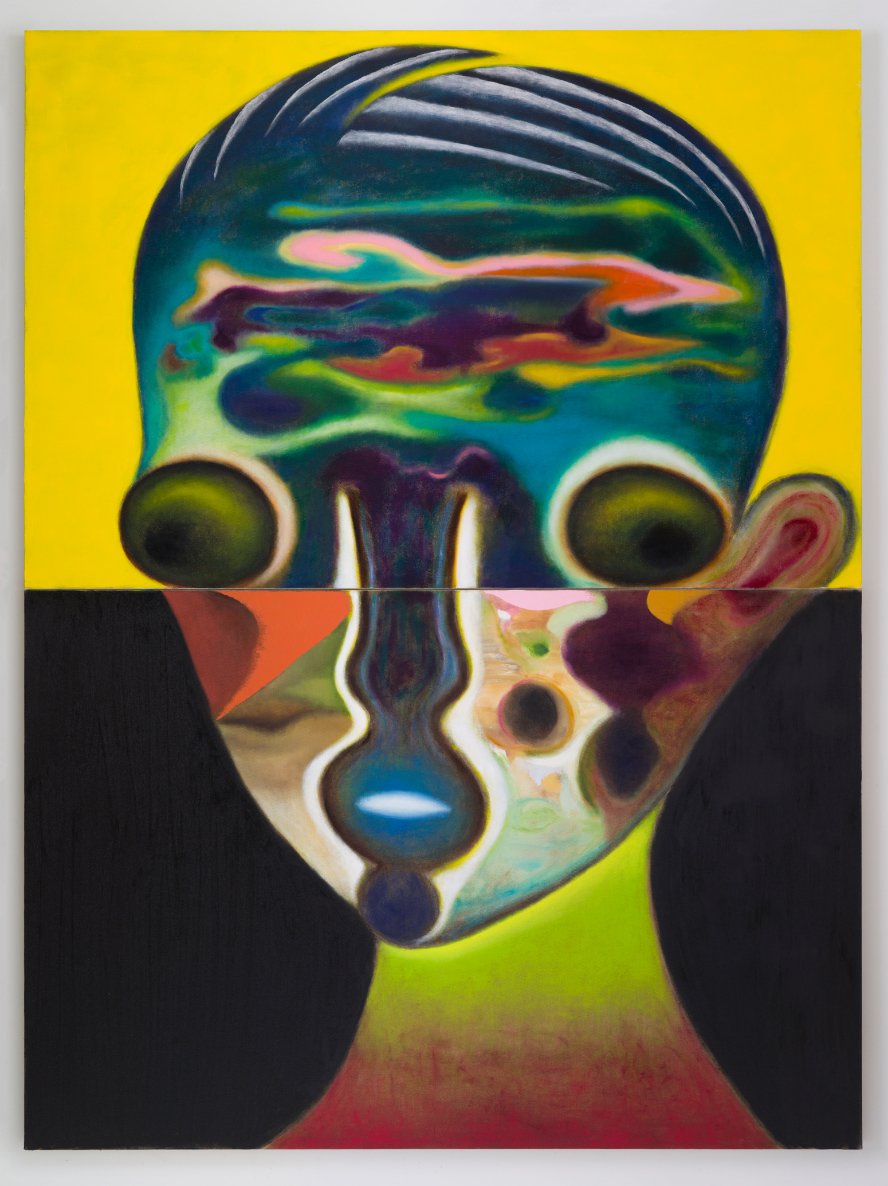

The distinctive appearance of his faces, with their enlarged eyes, often without pupils, the whole shaped by nose and mouth, the impression of being covered with ritual makeup, all this has numerous echoes in the fantastical prints produced in the 19th century, during the latter part of the Edo period and the Meiji era of Imperial Japan (1868-1912). Kato's work must be considered in relation to Utagawa Kunyoshi’s prints (1797-1861), one of the masters of the genre. In the work of Kunyoshi, the yokai are startling hybrids with bulging eyes, large jaws, and strange faces that seem like theatrical masks.

Looking at the hand-and-footless limbs of Kato's “characters,” one is reminded of Ichiyusai Kuniyoshi’s playful prints of "demon-shaped plants" (1844-1847). Yet, what sets Izumi Kato's creatures apart from all this pleasant, swaggering bluster is their silence. His work is characterized by a seriousness absent from the other works.

The totemic immobility of Izumi Kato's painted and sculpted works is strikingly melancholic. These figures are endless questions, beyond any specific place or time, as Japanese as they are ours, wherever we are. They challenge our gaze, drawing us in, interrogating what makes us mortal.

Izumi Kato is on view through July 29 @ Perrotin 76 Rue de Turenne.