Set across all floors of the raw remains of the historic Variety Arts Theater in Downtown Los Angeles, a haunting, confrontational, and revelatory history of moving images flickers in the darkness. Presented by Julia Stoschek and her preeminent Berlin-based foundation for time-based media, this is not an exhibition, nor a retrospective, nor a white-walled museum journey through chronological time. Described as an audiovisual poem, What A Wonderful World—edited (not curated) by Udo Kittelmann—moves from early cinematic experiments and silent film to contemporary video works by artists working today. The breadth of visual storytelling is astonishing. We sit down with Julia Stoschek and Udo Kittelmann to discuss their landmark paean to cinema itself. Click here to read more.

Arthur Simms's Caged Bottle Is a Delicate Balance Triggering Engines of Memory @ KARMA New York

text by Arlo Kremen

Arriving in New York City in 1968 at the age of seven, Saint Andrew, Jamaica-born Arthur Simms’ assemblages draw on the legacies of Duchamp and Rauschenberg. His new solo exhibition, Caged Bottle, at Karma New York shows works spanning nearly four decades from his studio on Staten Island. His sculptural works are made from found objects, often bound together by rope or wire. Rocks, bottles, toys, furniture, street signs, feathers, bones, and so many other discarded objects are manipulated by Simms into new forms. The binding of disparate objects together unifies them—a transformation of the many into a singular, fused work. Bug in the Cars (2024) is made from three toy cars, a roller skate, wire, and a bug, all stacked one atop another. The wire, wrapped around the glass encasing a bug carcass, cascades down to entwine two toy cars and the roller skate. A pink yarn webs the exterior of the sculptures into a fixed state, wrapped around the wheels of the roller skate, preventing movement. The third toy car, however, is quite literally disconnected. Free from the binding of wire and yarn, this car remains caged, likely able to move in the small space its cell affords, yet still a part of the overall sculptural figure—bound and unbound, unified and disunified, fixed and unfixed.

Simms’ use of yarn in Bugs in the Cars is relatively spare compared to his wrapping of rope in Sexual Tension (1992) and Spanish Town (2003). Both works are so densely bound with rope that their internal content becomes unclear from even a moderate distance. Whether it be the exact forms of wooden blocks in Spanish Town or whatever dark matter sits in the heart of Sexual Tension, a distinct separation occurs at the level of exteriority and interiority. The rope acts as a skin, concealing the beating organs it encases. Nearly spiritual, Sexual Tension, the earliest work in the show, although not relative to any human form, feels, in some sense, ghostly. A bodied quality sits hidden within an interior, inaccessible to onlookers, and can be directly encountered only through its shroud of hemp, while only the presence of an interior object is intimated.

Simms continues his interest in the spiritual in his works inspired by Congolese Nkisi (vessels for spirits or medicinal substances to resolve disputes, enforce justice, heal, or harm enemies). It is possible to argue that perhaps when creating Sexual Tension, Simms was already thinking of Nkisi, sculptures that are at times seen wrapped in rope, but his inspiration becomes more clearly articulated in The Knife and the Hammer, Fear of Aggression (1994). Mimicking the Nkisi in his puncturing the work with nails and knives, he activates the spirit within this totemic figure. The work is exhibited here for the first time but was assembled while working at the Brooklyn Museum as an art handler in the early 1990s, when Simms became fascinated with Nkisi and Central African throwing knives. The work, in its vertical orientation, features a slab of wood perpendicular to the floor, appearing nearly cross-like. In his bridging together of Christianity and Congolese spirituality, he reckons with art history. Art objects are manifested in the show as being inseparable from cultural modes of metaphysical belief.

Just as much as his work might be about spirit, Simms pays quite a bit of attention to form. In his exhibited paintings, Simms propounds the strength of the line. With a collection of works from 2025 whose titles begin with “Search for form” followed by a number indicating their order, Simms demarcates exactly what is at stake in these works: the power of a line to define a form. He uses lines to create forms, to separate blocks of color, and to provide forms with loose details. These works apply lines identical to his Retablos from 2015 that continue his interest in spirituality. Two of the three retablos in the show, Retablo 5, Staten Island, and Retablo 1, Lois Dodd, are, unlike his searches for form, representative of something (Staten Island and Lois Dodd, respectively). He used the same techniques of line as used in 2015 as he did a decade later, studying the distillation of forms to lines and color, in a manner quite similar to Arthur Dove, and in the case of Lois Dodd, Marius de Zayas’s absolute caricatures. A throughline could be drawn from his acrylic paintings on wood and aluminum to his sculptural practice in his continued interest in rope and wire, linear forms. Simms explores the potential of the line as a sculptural gesture, something that can, of course, be used to bind and attach, but also the line as something that can conceal, mystify, and define interiors and exteriors, as is the case with Sexual Tension. He thinks of the line’s bulk—when wrapped repeatedly over itself, the line becomes its own form rather than a tool to define a form.

Simms’ lines, particularly his ropes, are also soaked in memory. Being made of hemp, the use of rope betrays its presence before laying eyes on the works, with its pungent scent. Simms has spoken in interviews about his childhood memories remaining in smell and sound; thus, the olfactory dimension of the material triggers engines of memory. Many of his memories are related to the music he heard as a child, describing music as a process of layering and the coalescence and accumulation of sounds into a single work. As such, the binding feature of his linear forms refers back to his childhood.

Arthur Simms

The Knife and the Hammer, Fear of Aggression, 1994

Rope, glue, hammers, wood, knives, blades, wire, metal, screws, stones, monetary note, nails, cobblestone, and pencil

107 1/4 x 35 x 15 in.

© Arthur Simms. Courtesy the artist and Karma

In the exhibition’s titular work, Caged Bottle (2006), Simms tests the strength of the line in the most literal sense imaginable. Using both rope and wire, Caged Bottle is a balancing act between a deconstructed toy bike wrapped in rope and a recycling bin-like structure made from wires and a bike wheel. Glass bottles and an assortment of other objects fill the interiors of the two sides, providing a distribution of weight that allows Caged Bottle to balance its wheels on a small platform without tipping and crashing, which would result in the unfixed glass bottle in a birdcage tumbling off and shattering. This work is all about precarity. But in using the linear forms of wire and rope to hold it all together, the halves can balance each other, preventing the destruction of the caged bottle. In this display of Simms’ work, presenting his paintings and sculptures together for the first time, alongside his interest in art history, the spiritual, the cultural, and memory, the artist’s formalist attitudes are made clear, positioning him as a unique artist undeniably worthy of this spike in recognition after so many years flying under the radar.

Arthur Simms’ Caged Bottle is on view through February 14 @ Karma, 22 E 2nd Street, New York City.

Arthur Simms

Caged Bottle, 2006

Rope, wood, glue, bicycles, metal, bottles, and wire

50 x 62 x 36 in.

© Arthur Simms. Courtesy the artist and Karma

Narcissister’s “Voyage Into Infinity” Points to the Hidden Instability of the System

Narcissister, Voyage Into Infinity, 2024. Photo by Walter Wlodarczyk. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

text by Emma Grimes

Last month, NYU Skirball hosted Narcissister’s Voyage Into Infinity, a one-hour performance that originally debuted at Pioneer Works in 2024 and returned to the stage with a pointed timeliness.

The show’s title comes from the Bad Brains’ song of the same name. Pioneers of hard-core punk, and famously one of the only Black bands of the genre. It’s this disruption of easy assumptions that forms the conceptual foundation of Narcissister’s show. Framed as a “contemporary, feminist revisioning” of The Way Things Go—Peter Fischli’s and David Weiss’s landmark video that presents an elaborate chain reaction—Narcissister interrogates the systems we build while exploring the relationship between control, entropy, and power.

Fischli and Weiss’s 1987 video appears to be filmed in one shot, but it’s actually a tightly edited illusion, splicing together over a dozen individual clips. What looks like chaos was actually planned, and what looks like inevitability was really constructed. Their Rube Goldberg machine is made of an array of heavy, industrial materials, shrouding the work in a way that unmistakably reads masculine—which Narcissister untangles. While Fischli and Weiss present this smooth, inevitable progression, Voyage Into Infinity underscores the speed bumps and hesitation.

The performance begins with a woman crawling out of a wooden structure that looks like a treehouse; her face hidden behind one of Narcissister’s signature masks—smooth, artificial, and an exaggerated distortion of beauty standards. She wears a hyper-feminine dress, as though it were torn right off a plastic doll, and begins wandering the stage. Unlike the implied male hand behind The Way Things Go, she’s part of the machine.

The stage is crowded with a haphazard array of objects—half look like they’re from a junkyard, half from an estate sale. There are ladders, a marble sculpture of a muscular athlete playing discus, a see-saw, and much more. It’s Narcissister’s Rube Goldberg experiment, waiting to be propelled into motion.

A few minutes later, a second masked woman emerges from the structure, wearing the same dress in another color. Then a third. The characters are figuring out how to initiate the machine, and the experience is like watching a movie that didn’t cut out its dead time. Though most of the performance consists of these in-between moments, it’s never boring or idle.

At one point, one of the performers stacks empty Home Depot-style paint buckets into a pyramid, only to have it knocked over later. Later, those buckets are hung from the handlebars of a bicycle, which another character rides across the stage.

One could spend hours analyzing every detail, but to speculate too earnestly about each object’s meanings and the characters’ feats would feel almost superfluous. More significantly, the machine rarely behaves according to expectation. Its forward momentum relies on constant intervention from the masked characters, who interfere every time entropy poses a threat. Their role is to enforce the rules of the system and keep the machine working as designed, regardless of whether it makes any sense or collides with the messy realities of human life.

The most unforgettable image arrives at the end of the show, following a wonderful musical interruption by Holland Andrews and a live band. The three characters line up near the edge of the stage, wearing their dresses again, and hold an absurdly long string with a bundle of colorful balloons attached. They pull the string down and begin popping each balloon with their bodies. At times, their actions look like convulsions, spasms of energy wholly committed to wrecking.

Why inflate balloons only to obliterate them? Why stack a pyramid of buckets only to push it over? Their gestures reflect a form of power whose only objective is in asserting itself.

Narcissister, Voyage Into Infinity, 2024. Photo by Walter Wlodarczyk. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

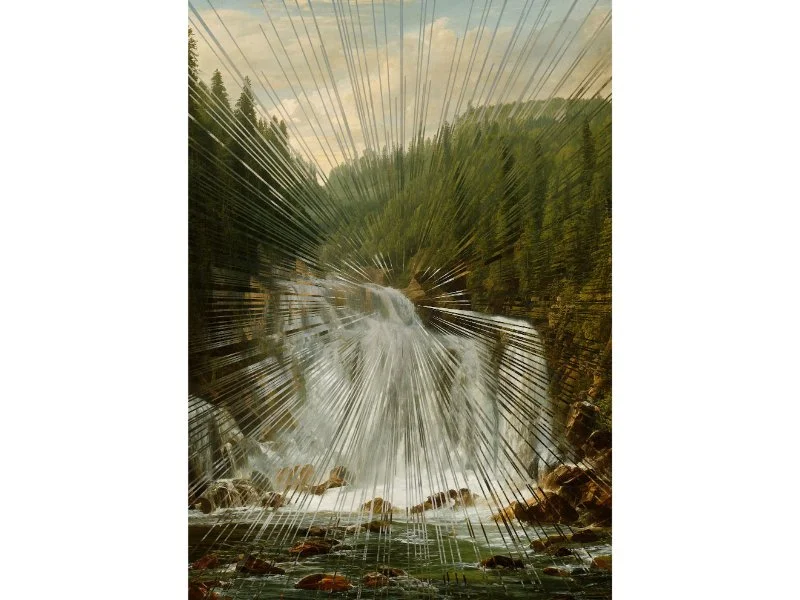

Alexis Rockman Remembers Earth with Bittersweet Resignation @ Jack Shainman Gallery in New York

Alexis Rockman

Lake Athabasca, 2023

oil on wood

48 x 40 x 2 inches

text by Hank Manning

Fire pervades Alexis Rockman’s paintings, on view now at Jack Shainman Gallery in Chelsea. Fires burn down forests, pollute the atmosphere, and even rage through snowy environs. Small nascent flames feel more ominous than those that have left entire forests ashen, as we can easily foresee the death to come. Rockman portrays bodies of water in the foreground, as if he has retreated to the one place where fire can’t burn. These bodies reflect much of the devastation on land, as well as the exhibition’s title, Feedback Loop. They emphasize the accelerating nature of this destruction. The works’ titles—including Karaikal Beach (India), Lake Tanganyika (East Africa), Osa Peninsula (Costa Rica)—attest to a global reckoning that is pointedly addressed when viewing the series as a whole.

Alexis Rockman

Pioneers, 2017

oil and alkyd on wood

72 x 144 x 2 inches (overall)

Set almost entirely underwater, Pioneers is the only landscape in the show that is completely devoid of fire. It portrays the wide range of lifeforms, from cyanobacteria to a 20-foot sturgeon, found in the Great Lakes. The sun, shrouded by smoke in other paintings, rises in the center like a beacon of rebirth. It is there that the animals turn their gaze. As the largest work in the exhibition, this painting is a reminder of the continually rising sea levels driven by climate change. But this is not a silver lining of global warming for sea life. Even here, reminders of human impact proliferate. The painting, in fact, can be seen as a timeline of our impact on the environment. On the left, a mammoth skull sits by an ice shelf, highlighting the role that hunting played in their extinction during the last ice age. In the center, a sunken ship rests on the seabed. At right, a shopping cart has become the home of zebra mussels, and a still-afloat ship pollutes the sea with an immense green blob of ballast water.

Alexis Rockman

Rio Tigre, 2023

oil and cold wax on wood

48 x 40 x 2 inches

Human life, as opposed to its traces, is conspicuously scarce, visible only on close inspection. In a few paintings, nondescript solitary figures sit on small boats watching the destruction on land. In other paintings, similar boats appear unmanned. They are isolated and powerless in the face of fire. Like the similarly isolated moose, bees, and birds, the remaining people have become victims of our poor stewardship, leading to the loss of their natural habitat.

Alexis Rockman

Raccoon, 2017

sand from Cuyahoga River, Whiskey Island, and acrylic polymer on paper

12.75 x 16 x 1.5 inches (framed)

In the exhibition’s final room hang sixteen portraits of animals and plants found in the Great Lakes. Unlike the previous paintings, these minimalist drawings—made from sand, soil, or coal dust from the area—mostly contain only one figure, each rendered in an individual color. Without the context provided by the other works, they look like the types of anatomical sketches a biologist might draw and describe in a notebook. These species’ histories have been profoundly shaped by human activity. The horrifying, parasitic sea lamprey followed the Erie Canal after its construction in 1825 to the Great Lakes, where it has been an invasive menace ever since. During the late 19th century, North American wood ducks were introduced into Europe and Asia for their aesthetic appeal as ornamental waterfowl. Shortly after the turn of the century, raccoons were also brought to Europe as part of the growing fur trade. These invasive species rapidly cause disorder and death in their new ecosystems.

Alexis Rockman

Forest Floor, 1990

oil on wood

68 x 112 x 1.75 inches

Looping back to the beginning, we look again at Forest Floor, Rockman’s oldest painting on display, at the entrance. The worms, spiders, and other small beings (an ant dwarfed by an acorn provides a sense of scale) form an intricate ecosystem, somewhat camouflaged, but seemingly more full of life than the larger landscapes. Their size suggests vulnerability, while their diversity—the longer we look, the more we see—suggests both their importance to a natural balance and the strength that comes with numbers.

Rockman admits that while he has continued for decades to paint natural environments, with encyclopedic detail, his motivation has changed. In the 1980s and ’90s, he thought the general public had “an information deficit,” so his work must warn of what’s to come and demand change. Later, he resigned to the idea that “neither I nor my work were going to save the world.” We have entered a feedback loop, where desecration begets further desecration. If we cannot preserve the environment, at least we can remember its beauty through art.

Alexis Rockman: Feedback Loop is on view through February 28 at Jack Shainman Gallery, 513 West 20th Street, New York

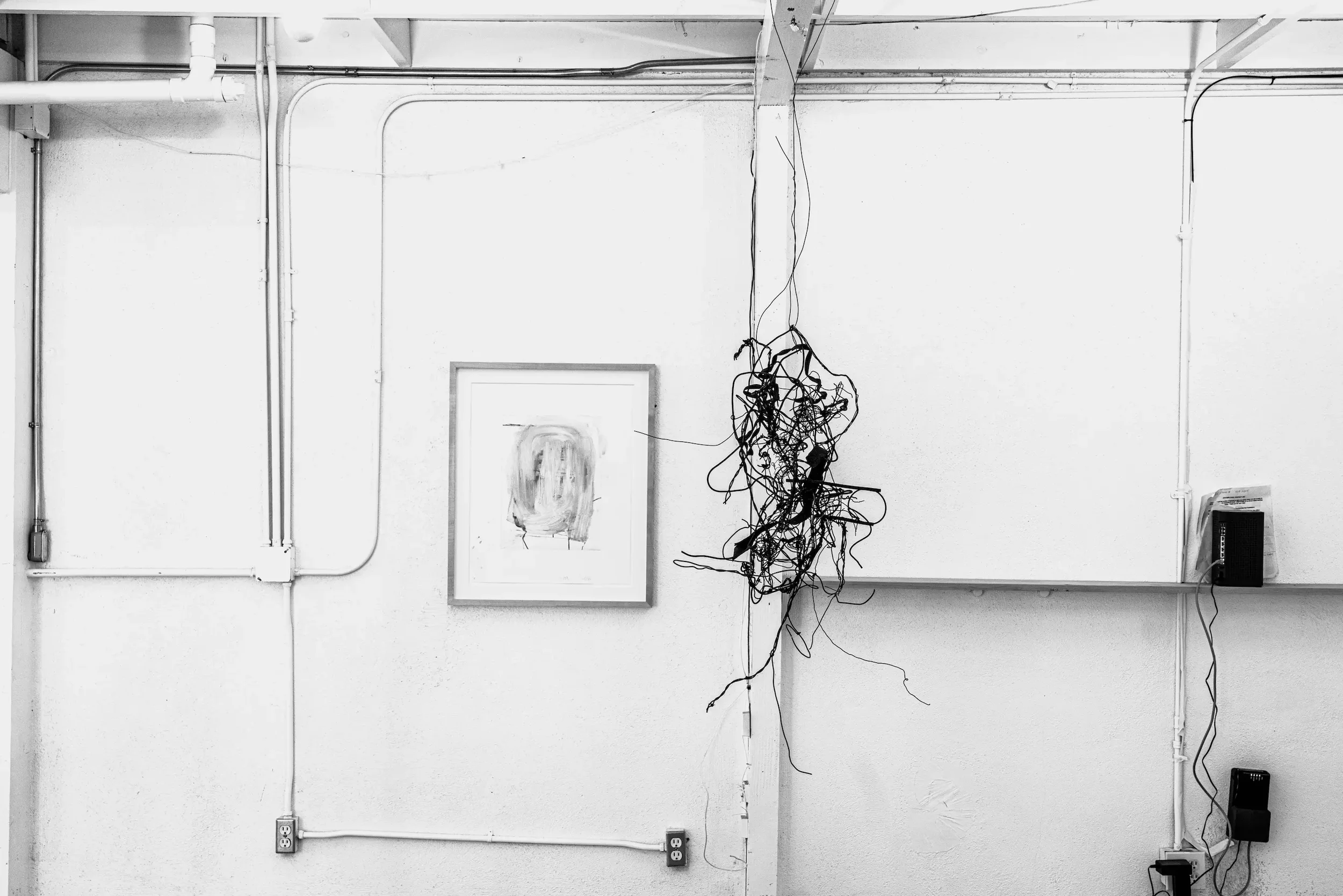

Christopher Wool’s See Stop Run Finds Its Home in the Desert

Courtesy of Christopher Wool

text by Emma Grimes

Walking into Christopher Wool’s See Stop Run exhibit in Marfa, you’re first confronted by a massive, spiderweb tangle of cast pipes. The sculpture sprawls across the center of the room without a clear point of origin: knotted and unruly. It feels like some kind of infrastructural system, rather than a single object, mirroring the subjects that fill Wool’s nearby photographs of old tires, scattered debris, and everything in between. To Wool, the natural world is inseparable from human waste.

The show spans four rooms across two neighboring buildings, holding a mix of sculptures, photographs taken locally in Marfa, and paintings.

When curator Anne Pontégnie first conceived of See Stop Run, she said that she wanted to get away from “the neutrality of contemporary art spaces, galleries, and institutions” and find somewhere in New York City—where the show originally ran—where the work “could interact with something other than a blank slate.” The show’s first iteration took place in an old, derelict office building in downtown Manhattan, and critics praised how the paintings and sculptures engaged with the space’s cracked floors, exposed wiring, and peeling surfaces, creating what a New York Times critic described as “visual rhymes.”

When the exhibition moved to Marfa in the spring of 2025 and took up space in the Brite Building, the presentation changed. It’s now in exactly the kind of pristine, white-walled space that Pontégnie wanted to avoid. Only one of the rooms contains the same wildness as the New York show, and this has the impact of lessening the dialogue between Wool’s work and its surroundings from shouts to whispers.

Courtesy of Christopher Wool

The exhibition here in Marfa is thoughtfully curated, but it doesn’t feel accurate to describe it as controlled chaos exactly, because what makes Wool’s work so compelling is how little it wants to be controlled. Most of the show does unfold in white gallery walls, but one room upstairs has a kitchenette, and another resembles the environment of the original New York show. Here, there are holes left behind by old nails and cracks in the floors. The wear and tear of the building—alongside the refrigerator and sink—feels as meaningful as the art itself because Wool’s work never seeks to dominate the space; it only asks to live in it.

One of the clearest examples is a wiry sculpture suspended from the ceiling, held by a black cord looped over a silver hook. It’s not immediately apparent where the artwork ends, and the means of display begins. Is the cord a part of the sculpture or just what’s holding it up? Wool seems to be testing the limits of his own work.

If a wire slipped loose or the floor cracked underfoot, or perhaps if one of his hanging sculptures fell to the ground, that wouldn’t change anything. It might even add something. And even though the Marfa iteration of See Stop Run offers less in terms of its setting, it ultimately delivers something even more compelling.

Courtesy of Christopher Wool

Courtesy of Christopher Wool

This comes in the form of three outdoor sculptures, which require a short drive to see, that feel like both the show’s natural conclusion and its highlight. Placed directly in the Chihuahuan desert, the works move forward from interacting with artificial space into dealing directly with the natural world as it is.

The steel forms resemble things already scattered across the landscape— tumbleweeds and tree roots and branches—but unlike the natural parallels, these ones don’t move or decay. Gazing at them, you can feel the human hands that meticulously crafted them. And meanwhile, the real desert continues its course all around them, indifferent. The sun rises and sets. The mountains stand tall.

In this way, Wool sets up a confrontation between two kinds of being: the natural world, which is alive precisely because it changes and dies, and his hand-crafted sculptures, which can endure only by refusing to be part of that cycle. Standing among these works as the wind forcefully blows and the Texas sun beams, you hover between these two modes of existence: the steel that combats mutability and the real, organic matter that changes, blows away, disappears.

See Stop Run is on view through Spring 2027 in the Brite Building, Marfa, Texas.

Otherwise Part IV: Operational Aesthetics: Dopaminergic Media, Deepfakes, CoComelon, the Kardashian–Jenner Conglomerate, and the Long Tail of the CCF

From the White House X account

by Perry Shimon

Following the previous essay, we find that while in the more contemplative corners of the contemporary art world, spatialized philosophical questions endeavor to idiosyncratically suture the anomic wounds of modernity, the more statistically significant mode of visual culture today can be primarily understood as operational (in a less philosophical sense): media produced and instrumentalized through computational vectors with clearly defined goals—largely financial, increasingly automated, and frequently without the necessary involvement of human agents and audiences. The late artist and theorist Harun Farocki offered the concept of operational images to describe images functioning beyond the concerns of representation and spectatorship, which perform operations most consequentially in service of corporate and military interests. This can include security applications, industrial automation, data-driven governance, and automated warfare.

Massive infrastructures supporting the teleological and operationalized image have proliferated since the time of Farocki’s initial conceptualization, and the concept is useful today in describing the vast networks of algorithmically governed visual culture transacted via monopolized social media platforms trafficking in attentional, behavioral, and data-extractive economies. This choreography of operational media within platform capitalism, along with the internalization of the imperatives of attentional economies, shapes our visual culture to a critical extent. Much of the media encountered in increasingly hyperspecified algorithmic operations serves the function of commanding attention, producing commoditized data, generating clicks, realizing advertising revenue, and steering behavior. Images today look back at us, collect intimate information, and act insidiously on that information toward financialized ends.

Sophisticated behavioral industries, built with a scientific rigor almost entirely unmoored from ethical considerations, have contributed to a neurochemically calibrated form of dopaminergic media deployed to addict users. In some cases, particularly among vulnerable demographics such as children and teenagers, users become so chronically habituated to these technologies that they spend the majority of their free time subjugated to them. A consequential and compounding quantity of media today operates at the level of addiction and compulsion.

The exponential rise of data-powered operational media exhausts human-scale consideration, and an opportunistic market endeavors to capitalize on the datafication of the world through ever more energy-intensive infrastructural projects for the capture and processing of data. This creates a Jevons Paradox of compounding energy usage, wherein even technological gains in efficiency do little to stymie the energy expenditures produced by further adoption and intensified use. In the name of data rationalism, its questionable promises, and its primary function of capital accumulation, enormous, extractive, and ecologically ruinous infrastructures are being imposed on the public to our collective more-than-human detriment.

Through the abstracted logics of datafication, we are given quantified glimpses into an ecological polycrisis initiated by the same base economic structures and technologies of administration at work in the monopolization of the internet. It stands to reason that the driving forces of social and ecological devastation—limitless growth-based economies, carbonized energy infrastructures, animal agriculture, automobilism, and so on—are not suffering from a lack of data (or from the massive energy-intensive private data infrastructures required to datafy the world) in order to remediate them, rather from a lack of political and social will, as well as the redeployment and redistribution of rights and resources.

The Kardashian–Jenner conglomerate

The Kardashian–Jenner conglomerate offers a generative case study of an operational aesthetics built on a distinctly liberal, capitalist hypersubjectivity broadly enacted through social and traditional media to market goods primarily produced in industrial and plantation modes. The fetish of liberal subjectivity is superarticulated in their performative, pharmacological, and surgical construction of the fully commoditized and optimized self, and their branded subjectivity is leveraged into endless variations of products, promotions, and other forms of capitalization. The Kardashian–Jenner conglomerate maintains a highly integrated, multiplatform, cross-industry portfolio spanning beauty, cosmetics, fashion, fragrances, jewelry, accessories, food, beverages, health, wellness, media, technology, home, lifestyle, brand collaborations, and luxury partnerships—a Gesamtkunstwerk of neoliberal operational aesthetics.

CoComelon

CoComelon, the second most viewed YouTube channel in recent years—purchased by a Blackstone-funded “next generation media company” founded by former Disney executives for three billion dollars and now part of a vast conglomerate churning out dopaminergic children’s content—provides an instructive case study of profit-motivated operational media targeting children at the earliest stages of development. In this case, the primary operations at work are the capture of children’s attention to earn advertising revenue for host platforms, the securing of streaming deals, spin-offs, merchandise, licensing, or IP franchises, and the training of emerging generations of lifelong consumers. In Jia Tolentino’s 2024 reporting, we are given a snapshot of a capital-fueled children’s content mill garnering sixty billion minutes of YouTube streams in the first quarter of 2023, while lead writers earning barely livable five-figure salaries in Los Angeles are laid off during restructuring exercises. This provides yet another example of the trajectory of unregulated capital in its ruthless expropriation of labor and drive toward market domination—exploiting and automating its own means of production wherever possible while remaining fiduciarily bound to the expansion of children’s attention capture and potential profits.

It remains to be seen what regulatory measures, if any, will be implemented to safeguard children from content designed to capitalize on their biologically evolved dispositions through a hallucinatory sensorium of increasingly machine-generated nonsense. This logic of “optimized engagement” holds across nearly every feature of platform capitalism: from search to social media, and of course e-commerce. The result is an arms race for attention, while a staggering portion of the technologized world has developed acute addictions to dopaminergic media and attendant psychosocial maladies, increasingly acquiescing to the behavioral imperatives of the animating marketers. We might add technologically administered dopaminergic media to opium and sugar on the list of the most widely deployed and socially debilitating drugs distributed by multinational corporations.

The Vatican, Caleb Miller for Unsplash

Anna Church for Unspash

Operational media—media intended to produce particular outcomes in their audiences—is, of course, hardly unprecedented. In the Western tradition, the aesthetic regime of Christianity, with its architectures, crosses, paintings, icons, elaborate clothing, and rituals, accompanied and legitimized perhaps the most extensive imperial bid for global power in human history. The extraplanetary global infrastructure of the internet constitutes an epochal development at an unprecedented scale and the culmination of the so-called Western project in the United States marks the most powerful imperial empire to date.

It is instructive to examine the cultural methodologies of American imperialism during its twentieth-century bid for global hegemony. The Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF)—a CIA-adjacent organization that at its height in the 1950s and 1960s operated in over thirty-five countries, founded or sponsored more than twenty journals, organized hundreds of conferences, and exerted influence over university departments, literary prizes, translation programs, arts councils, research institutes, and institutional collecting practices—became a primary instrument of liberal imperial soft power. It was among the most influential cultural apparatuses of its era, shaping global definitions of “freedom” through culture and ideas while promoting a liberal conception of individuality and a distrust of socialist forms of art and collective solidarity. Its strategies were complex and often involved the selective embrace of left or socialist positions in order to inoculate audiences and neutralize political power. The paradigm of the lone genius artist, disavowing collective politics and hyperfixated on identity, was bolstered through this coordinated international network and remains dominant today.

It is worth considering which legacies and continuations of these initiatives persist, whether analogous programs remain operative, what values and strategies they advance, and which foundations, institutions, and artists administer them.

In my ambivalent proximity to the art world, I have observed recurring motifs from the liberal project alongside emerging practices that raise questions about their ubiquity and reproduction along vectors of liberalization. These may be provisionally grouped into a schematic that resonates with the CCF program: hyperindividual, hypernormal, science-fictional, ornamentalist, obscurantist, and melodramatic.

Juliana Huxtable

The hyperindividual artist presentation foregrounds the extreme articulation of performative selfhood, often positioning the artist’s own identity as the artwork or producing highly idiosyncratic series that emphasize individual distinction. The American artist, writer, performer, DJ, and cofounder of the New York–based nightlife project Shock Value, Juliana Huxtable, offers one example among many.

The hypernormal, following Adam Curtis’s 2016 documentary HyperNormalisation, is characterized by the production of unrelenting misinformation, misdirection, co-option, distortion, and overwhelm. The result is a paralyzed, passive, consumer-oriented subject incapacitated by epistemic exhaustion. An e-flux text describing Trevor Paglen’s 2023 film Doty illustrates this condition:

Richard Doty is a former Air Force Intelligence operative whose job at Kirtland AFB in New Mexico involved creating and disseminating disinformation about the existence of extraterrestrial spacecraft to UFO researchers.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Kirtland AFB was home to a wide range of highly classified technology experiments involving lasers, stealth aircraft, and nuclear weapons. Strange phenomena in the skies above the base piqued the interest of amateur and professional UFO investigators. Doty’s job was to recruit UFO researchers to be informants to the Air Force about goings-on in the UFO community and to spread military disinformation about UFOs among their peers. To accomplish this, Doty supplied fake documents to UFO investigators purporting to tell the “truth” about government involvement with extraterrestrials.

On the other hand, Doty insists that UFOs are real, that the government is in possession of crashed spacecraft, and that he was read into a top-secret military program detailing the history and status of US-alien relations.

In this video, Doty discusses the craft of disinformation, and describes operations he ran against UFO researchers as well as elements of the “real” top-secret extraterrestrial technology program that he says continues to this day.

The film was presented as part of a tour he called "YOU'VE BEEN F*CKED BY PSYOPS: UFOS, MAGIC, MIND CONTROL, ELECTRONIC WARFARE, AND THE FUTURE OF MEDIA" The experience of encountering this work, like much of today’s hypermediated political spectacle, is one of profound confusion and apathy—an affective state that serves a political function in maintaining the status quo and creating a climate of confusion and paranoia.

A proliferation of science-fictional futurisms is institutionally supported across the liberal art world today—Afrofuturisms, Latinx Futurisms, Indigenous Futurisms, Arab and Gulf Futurisms, Sinofuturisms, Queer Futurisms, and others. While these movements are heterogeneous, common tendencies emerge: highly aestheticized, idiosyncratic, and performative representations of essentialized identities produced by professional artists within liberal institutions. These speculative scenarios rarely articulate concrete political demands or enduring institutions, raising questions about how the commodified spectacle of identity representation serves existing power relations as well as the artists who perform them.

Neon Wang for Unsplash

A frequently cited instance of CCF Cold War cultural politics is the celebration of abstract expressionism as a vehicle for depoliticizing art while fetishizing individual self-expression and still, of course, producing an unmistakable series of collectible works. This tendency persists today in the celebration of ornamental art co-emerging with the largest unregulated market in the world. Such works, traded globally, may appear politically anodyne, yet their politics might be better characterized as a form of financialized smoothness, for their ability to move through the circuits of the international art market. The mediagenic immersive installation optimized for social media reproduction can be understood as an outgrowth of these values.

Obscurantism, as used here, refers to the deliberate rendering of historically significant subjects as inaccessible through excessive abstraction, obfuscation, or academic artspeak. This mode is widely recognized across liberal art institutions, where opacity often substitutes for substance.

Melodrama has become one of the dominant narrative forms of late-capitalist culture, not simply as a genre but as a social technology that translates structural contradictions into private emotional crises. In melodramatic storytelling, whether in soap operas, prestige television, or award-winning literary fiction, social conflict is consistently reframed as betrayal, infidelity, moral failure, or psychological damage. Collective institutions appear either absent or corrupt; solidarity is fragile and naïve; and trust is often punished. Structural forces such as economic precarity, class antagonism, or political disempowerment are displaced onto intimate relationships, where they are experienced as tragic inevitabilities rather than as problems open to collective action. This narrative logic produces what Mark Fisher described as a form of capitalist realism: a cultural atmosphere in which social breakdown is endlessly represented yet never politicized, generating a hedonic familiarity and romanticization with fracture that forecloses alternative imaginaries. Social cohesion becomes ever more remote through overexposure to stories in which cohesion is repeatedly shown to be impossible.

Prize culture and elite literary institutions reinforce this dynamic by systematically rewarding narratives that aestheticize rupture, transgression, and psychic damage while treating collective projects as suspect, authoritarian, or artistically naïve. As Frances Stonor Saunders documents in The Cultural Cold War (2000), liberal cultural institutions during the Cold War did not primarily promote positive visions of collective liberal society; rather, they elevated forms of art and writing that foregrounded alienation, ambiguity, and individual moral struggle, thereby positioning collectivism itself as culturally regressive or dangerous. This logic persists in contemporary cultural economies, where awards function as mechanisms of canon formation that legitimate a narrow range of affects and narrative structures. The result is not just the celebration of “dark” or “complex” art, but the normalization of social atomization as depth, mistrust as realism, and betrayal as the basic grammar of human relations. In this sense, melodrama and prize culture operate together as instruments of affective counter-collectivism: rendering collective values implausible within the dominant cultural imagination.

It serves us to more closely examine how operational media—co-emergent with neoliberalism, financialization, platform capitalism, and American imperialism—shapes prevailing conceptions of art and visual culture. By understanding the forces and inertias through which these ideas have come to ubiquity, we are better equipped to look outside and beyond them in the creation of the otherwise.

Otherwise is a series on neoliberal contemporary art and its unbounded remainders by Perry Shimon.

Otherwise Part V: Landscape Aesthetics and the Liberal Commons

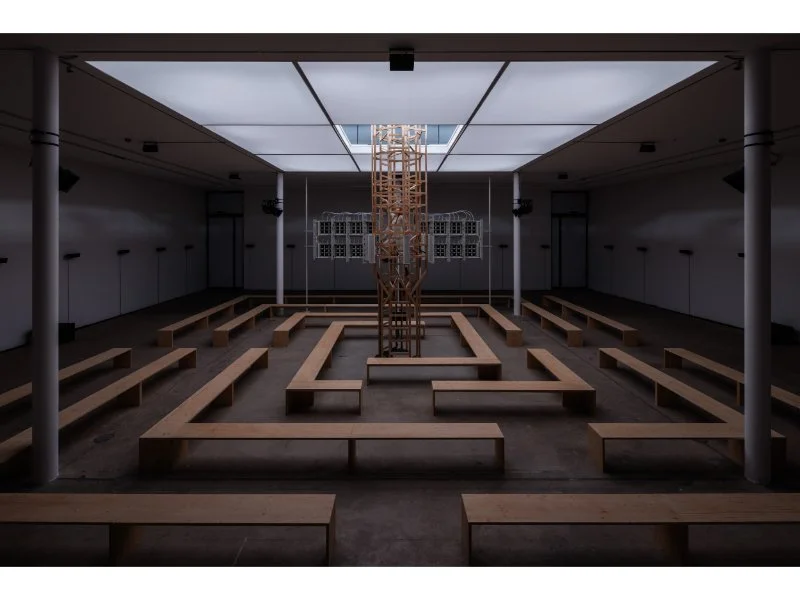

Herndon & Dryhurst's "Starmirror" @ KW Institute for Contemporary Art

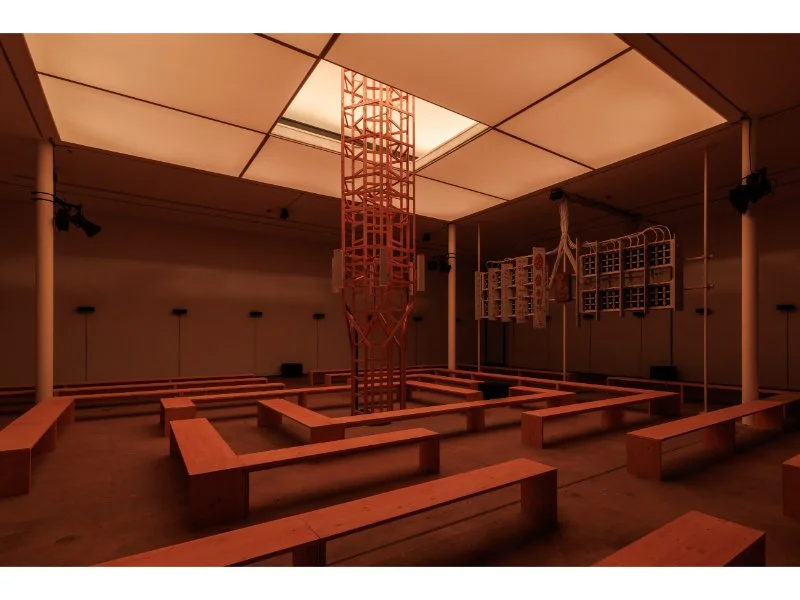

Installation view of the exhibition Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst–Starmirror at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2025

text by Arlo Kremen

Born in Johnson City, Tennessee, and Birmingham, England, respectively, artist duo Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst are two of the art world’s most outspoken figures for AI integration. Having attended Stanford while still being partly based in the Bay Area, Herndon’s continued application of AI models in her musical compositions and artwork remains unsurprising, as is her angle on this burgeoning technology. Partnering with Dryhurst, who has a history of advocating for internet decentralization and involvement in blockchain tech (think NFTs and social tokens), they have advanced discussions of AI through their music releases and installations since 2015. The KW Institute for Contemporary Art is the home for their current show, Starmirror.

Inspired by the much-admired Benedictine abbess and polymath from the Rhineland, Hildegard von Bingen, the show trains its attention on synchronicities between AI and the abbess’s own vision of divine order, all while considering the new role of authorship, whose precarity has undergone much turmoil in current AI-related discourse. Starmirror ultimately vies to reconceptualize human-AI collaboration and production, imagining beneficial and innovative relationships between two entities that many find existentially at odds.

Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst with sub

Arboretum, 2025

SLA resin, PETG filament, steel nuts, bolts, and pine wood

Commissioned and produced by KW Institute for ContemporaryArt, Berlin and the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf

The first room hosts Arboretum (2025), a sculptural work entirely concerned with Public Diffusion, an image model reared on publicly owned and Creative Commons Zero images, shaping a foundation model solely on ethically sourced images. Arboretum’s model uses no privately owned or sourced images in its training, a feature of nearly all AI image models. Its dataset is free to access, forming a democratized model without specific ownership.

The artists built PD40M, the largest public-domain dataset to date. Compiled from 40 million, it continues to grow through participation. The Starmirror app prompts viewers to add to the commonwealth of images already accessible to the public in an effort to resist the common perception that AI image models force viewers into a passive position. ‘Slop’ is the thrown-around term used to define the visual excrement of internet aesthetics that AI is famed for producing. Here, AI is posited as capable of producing something greater than lowest-common-denominator symbols. Instead of being the receiver of information, the human becomes the feeder, using AI to decode and visualize patterns within shared human activity. This model necessitates escaping the algorithm, going outside, and searching. If anyone remembers the screen zombies of the summer of 2016, the Starmirror app is a lot like Pokémon GO, except it is about seeing the world, not collecting clout in a digital landscape. It is AI between technology and the world.

It’s a challenge to see the good in AI. Coming from a political background far outside the tech bubble, conversations around AI and pattern recognition are primarily centered on ICE’s collaboration with Palantir. That, regardless of intention and dedication to constructing a public-supporting commons, this technology will be appropriated and abused by government agencies and private businesses. Data will be bought, sold, and used to incriminate the most vulnerable. Perhaps this is naive, that all this is claimed without key information and the knowledge to differentiate models, and that fear-mongering over AI is possibly dangerous for other reasons. All of this might be true; none of it might be. But, regardless of how one might feel about such hesitations or the positive excitement provoked by the idea of such a work, the images produced by Starmirror, as one might expect, are layers upon layers of endless pastiche. So why is this at the KW institute? Starmirror is not about art. It is not about the capacity and ability of the image but about making sense of a database. This is where Hildegard von Bingen enters.

At the heart of Arboretum is a layered model inspired by Bingen’s 1151 play Ordo Virtutum. Using neumes (symbols from early Western musical notation) as a base layer, with an overlay of AI scrawlings generated by a model from Algomus, a team of researchers specializing in music modeling, analysis, and creation with AI. Here, the model composes a polyphony to create infinite variations of Ordo Virtutum that seek to pay her tribute by extending her legacy. Of course, the infinite iteration of her work neither pays her tribute nor extends her legacy. Such an approach to the authorship of a woman who died nearly 900 years ago is bizarre, to say the least. The product feels more like a mockery and bastardization than respect. For a play concerning the salvation of the human soul, protecting the soul from the devil who taunts it with worldly pleasures, the construction of a robot Hildegard von Bingen, in a removal of her holy dedication and soul, does nothing other than turn her work into a representation of those very earthly desires with which the devil taunts. The artists appear to care little about the actual work of Hildegard von Bingen, but about how AI can change it, add to it, and what AI can do when her highly interpretable and semi-illegible notation system enters a database.

Installation view of the exhibition Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst–Starmirror at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2025

In the main hall, The Ladder (2025) continues the duo’s fascination with the German abbess, who envisioned ladders as hierarchies containing tiers with angels and virtues bridging Earth and the divine. In a convenient synchronicity, computer scientist and psychologist Geoffrey Hinton described machine learning systems’ latent space diagrams, which are based on the stacking of neural networks, from a more foundational bottom to an increasingly complex top, as “ladders of abstraction,” affirming the ladder as a dual referent. In the space around The Ladder, different sounds encroach, charging the hall with the divine. Some works are from The Call (2024–25), a research and development project and exhibition by Herndon, Dryhurst, and Serpentine Arts Technologies; others are from surviving medieval works, some by Hildegard von Bingen herself, but intermixed are AI interpretations of Hildegard’s work. In conjunction with the show, the artists invite the Starmirror ensemble, volunteers, and choirs to visit and contribute their voices in call-and-response sessions to train an AI choir that is scheduled to debut in the summer of 2026 at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf.

Starmirror, perhaps more than an art exhibition, is a continuation of their experiment. The “art” of the shows is often secondary to figuring out how to coexist with, if not utilize, AI to serve people, not corporations—a highly respectable mission. But to take away a future in which AI might aid human creativity and art-making, at this moment, feels foolish. The show does not demonstrate the same level of care for the image or score as it does for the systems that produce them. So often, the show stressed the collaborative nature of their AI use. All of these folks come and share time, space, and their very bodies with each other and the AI choir they are building. The question that looms over the show: how is training an AI choir any more communal than the traditional choir? What is the difference in the aggregation of voices and beings other than the displacement and invisibility of the body?

Starmirror is on view through January 18, 2026 @ KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin.

Richard Linklater Offers a Sweet, if Tame, Ode to Jean-Luc Godard

text by Emma Grimes

Richard Linklater’s latest film, Nouvelle Vague, is a sentimental love letter to the French New Wave—that brief postwar period in cinema when a group of young critics with nerve and conviction just about altered every rule about how movies could look and how we should think about them. In celebrating these filmmakers, Linklater offers a pleasant and affectionate reminder of their originality.

The film opens in 1959, as Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows makes its Cannes debut, and a restless Jean-Luc Godard, still a critic at Cahiers du Cinema, is itching to direct his first feature film. Cahiers is now known as the breeding ground for these insolent critics-turned-directors that punctured the French film establishment. As critic David Kehr wrote, it was the start of “film criticism as a contact sport.”

To Godard, his role as a filmmaker was a continuation of his role as critic. He didn’t see them as two separate pursuits; rather, his films were his criticism too, just imparted differently. And soon enough, he got his shot at making that film with a script from Truffaut, allegedly based on a real crime story pulled from the newspaper. The eventual result, Breathless, is restless, improvised, and spectacularly alive.

Linklater succinctly captures Godard’s taut vision and stubbornness as a director. A significant portion of the film takes place in Parisian bistros, where the cast and crew lounge around, waiting for their cue from Godard. Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) and Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch) don’t rehearse their lines because there are no lines to rehearse in advance. Some days on set last just two hours. His peculiar and erratic filmmaking approach causes Seberg to doubt whether he has any overarching vision at all. She wants to call it quits at one point.

While some or all of these historical facts about the making of the movie may be familiar to cinephiles, it’s a pleasure to watch it all unfold on the big screen and in the hands of these actors. Guillaume Marbeck gives a brooding and very focused Godard, but Deutch steals the screen as Seberg. She is sharp, radiant, and elusive. You can immediately understand why Godard wanted to capture her unguarded, candid self.

And the rest of the Godard checklist, Linklater crosses off: his use of the handheld camera, on-location shooting, disregard for continuity editing, and his insistence on capturing spontaneity. The critic Armond White wrote in 2007 that half a century of familiarity with Breathless has bred “a certain kind of nonchalance” about the wildly original and trailblazing film. “The excitement of discovery is almost gone,” White writes, “meaning it’s time for rediscovery.”

Linklater succeeds at doing just that, allowing a modern audience to see it anew—to feel, perhaps for the first time, how pioneering and defiant these young filmmakers once were and how strange their perspective once seemed. We meet and spend a little time with other filmmakers, including Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Éric Rohmer, and Robert Bresson.

But in rediscovering Godard and his cohort of iconoclasts, Linklater inevitably folds something once radical into a consumable product with duller edges. This paradox is inevitable for the project he’s after, that of sincerely celebrating the New Wave’s pioneering achievements. Nevertheless, it risks feeling like one of those “vintage” t-shirts sold online—retro and unique in spirit, but mass-produced in reality.

Still, none of this diminishes the pleasure of watching this film. I loved every minute. The wood-fire crackling of the film reel, the warmth and ebullience of Deutch’s embodiment of Seberg, the beautiful imitations of original shots from Breathless—it’s all undeniably, intensely pleasurable.

But to truly honor Godard would mean scandalizing us again, making something unruly instead of sweet and digestible. Nouvelle Vague isn’t any fresher than convenience store candy, but it does taste just as nice and is impossible to resist.

An Interview of Ari and Eitan Selinger on Their New Film 'On The End' →

“He must have had a really bizarre experience. He was sitting on his porch watching the movie of his life.”

interview by Poppy Baring

On The End, directed by Ari Selinger and scored by Eitan Selinger, tells the story of Tom Ferreira, a mechanic living in Montauk at the end of the glamorized Hamptons town. The film, which is heavily based on a true story and was made within feet of the home that inspired it, is a highly emotional chronicle of a contestable yet ultimately good-hearted man being bullied by property developers. The film not only reveals issues of greed and corruption, but it also tells the story of love and loss between Tom and fellow outcast Freckles. With local actors Tim Blake Nelson playing the former and Mireille Enos as the latter, a certain intimacy with the community lends the film a sense of sincerity. In this interview, Ari Selinger and his brother Eitan Selinger discuss their fraternal dynamic, their choices behind the score, and they reflect on the real Tom who inspired the film and passed shortly after it was made. Read More.

Dawn Williams Boyd Inverts America's Racial Narrative @ Fort Gansevoort

Dawn Williams Boyd

Abduction, 2025

Assorted fabrics and cotton embroidery floss

45 x 67.5 inches

text by Hank Manning

In FEAR at Fort Gansevoort, Dawn Williams Boyd inverts American history, imagining a parallel universe where Black oppressors imported white slaves and have maintained an economy predicated on race-based exploitation for centuries. Her cloth paintings, made with textiles imported from Africa, all closely resemble canonical American ephemera, including historical photographs and advertisements. Maintaining this color-inverting framework, the gallery, for its third solo exhibition with Boyd, has painted its typically white walls black.

The exhibition quickly succeeds in making us hyperaware of our racial biases. The scenes depicted—enslaved people chained together on ships, hooded horsemen celebrating lynchings, peaceful protestors attacked by police and civilians—are so ingrained in our memories that we instinctively assign roles before noticing Boyd has reversed them. Even knowing the artist’s intent, standing before these explicit works, our minds still resist the uncanny world she constructs.

Dawn Williams Boyd

Brainwashed, 2025

Assorted fabrics and cotton embroidery floss

66 x 43.5 inches

In addition to these violent scenes, Boyd highlights the psychological violence that racism perpetuates in relation to the commercialization of cultural tropes. In a piece titled Brainwashed, a young Black girl, holding a black bar of soap, asks a white slave, “Why doesn’t your mamma wash you with Fairy Soap?” We are directly confronted with the immediate qualities we assign to the colors black and white, as well as how these perceptions affect one’s feelings of self-worth, particularly when learned at a young age.

Dawn Williams Boyd

Cultural Appropriation, 2025

Assorted fabrics and cotton embroidery floss

47 x 58 inches

More than 150 years after the de jure end of slavery in America, economic and social inequalities persist. In keeping with this reality, Boyd’s textile works generally proceed chronologically through history, but they offer no hint of progress toward integration or equality; the racial divide remains unambiguous. She further underscores the role of seemingly benevolent industries, like entertainment and medicine, in perpetuating racial inequality. We see white subjects forced into society’s most exploited roles, from dancing in banana skirts in service of the hegemonic class (at a Prohibition era nightclub in Harlem), to being the subjects of gruesome gynecological research (imitating the work of Marion Sims, the “father of gynecology” who performed studies on enslaved Black women). In the real world, Black patients disproportionately lack access to the advances their exploitation made possible.

Dawn Williams Boyd

The Lost Cause Mythos, 2025

Assorted fabrics and cotton embroidery floss

56 x 70.5 inches

In The Lost Cause Mythos, a reframed Gone With the Wind features a white mammy serving a Black Scarlett O’Hara. Boyd addresses the power of art in shaping and reinforcing societal myths, however, she refuses to entertain the “happy slave” stereotype, instead portraying a despondent attendant. White characters lose their individuality; in settings from the beginning of the slave trade to the present day, men and women sport identical short blond hair and appear either nearly nude or in plain white garments. This homogenization dehumanizes them, treating them as props devoid of personality. Their Black counterparts, by contrast, have diverse hairstyles and elaborate clothing in a variety of colors, with red—here a symbol of power—especially prevalent.

Today, the US federal government and many state governments are attacking DEI initiatives, legal protections secured by the Civil Rights movement, and the honest teaching of American history, denigrating attempts to right historical wrongs as “reverse racism.” Boyd’s stark work puts these unsubstantiated claims into perspective. It asserts the degree to which most Americans underestimate the ongoing legacy of systemic racism and emphasizes the role of emotion in our material world. We see fear in the eyes of everyone, from those experiencing the horrors below deck on slave ships to a fragile ruling class who feels existentially entitled to their privilege and is terrified of losing it.

Dawn Williams Boyd: FEAR is on view through January 24 at Fort Gansevoort, 5 Ninth Avenue, New York

Autre Magazine Hosts An Intimate Dinner Celebrating Women In Arts and Motorsports At The Miami Beach EDITION During Art Week

Last night in Miami, on the occasion of Art Week, Autre Magazine, in collaboration with Driven Artists Racing Team, hosted an intimate dinner celebrating women in art and motorsports. The evening honored racecar driver Zoe Barry, who graces the magazine’s FW25 “Work In Progress” cover, and highlighted the dynamic intersection of creative expression and high-performance racing. Supported by CADDIS, the gathering brought together cultural luminaries—including musician and artist Kid Cudi, George Clinton, Crystal Waters, Olivier Picasso, Jeffrey Deitch, Tony Shafrazi, Spring McManus, and more—who dined family-style under the stars at The Miami Beach EDITION’s Matador Terrace. The evening celebrated artistry, innovation, and the bold spirit of women leading in both the arts and motorsports.

Read An Interview of Author Tea Hačić-Vlahović on Her Latest Novel 'Give Me Danger' →

The structure of the natural and manufactured world may be a nodal web of endless coequal expansion, but if enough people accept a longitudinal hierarchy as their shared reality, mass hysteria ensues, and a social ladder becomes solid enough to climb. Such has been the case since the dawn of human imperialism, and ever since, those of us who can see the undressed emperor have always easily picked one another out in the crowd. I picked journalist and author Tea Hačić-Vlahović out from this crowd the first time I read her work. So, too, did Giancarlo DiTrapano, the late and legendary editor/publisher of Tyrant Books. A beloved champion of young and daring writers, DiTrapano resuscitated an indie lit scene that had been idling on life support for nearly a generation. He saw the hidden potential in writers like Hačić-Vlahović, whose unpolished prose needed just the right amount of elbow grease to elevate their natural patina. It was only a month before he passed in March of 2021 when Tea texted to tell me that he was planning to publish her second novel, A Cigarette Lit Backwards, and that she had incorporated a small anecdote I had shared with her a year earlier. Her third and most recent novel, Give Me Danger, builds on this lived reality, only in this fictionalized version, her lead character Val’s first novel is a lowbrow bestseller, and her dreams of gaining clout in the indie lit scene are dashed by the news of her would-be publisher’s demise. Val struggles to wade through the gatekeeping social climbers who constitute his outer entourage so that she can simply pay her respects, and her experiences navigating the pomp and circumstance of those who consider themselves the cultural elite are a left-of-center mirror reflecting under an alternating strobe of moody and halogen lighting. Read more.

Autre Magazine Presents Performa Biennial's Grand Finale with Mother Daughter Holy Spirit In New York

Last weekend, Autre magazine presented the grand finale closing event for the 20th anniversary of the Performa Biennial, co-hosted with trans rights fundraiser Mother Daughter Holy Spirit. A highlight of the evening was a special and rare performance from house legend Crystal Waters who performed her iconic track, “Gypsy Woman (She’s Homeless).” A very special thanks to Staud for the support. photographs by Oliver Kupper

Volta Collective’s Loneliness Triptych Questions the Source of Our Unsettling Discomfort with Solitude @ New Theater in Hollywood

text by Summer Bowie

photographs by Roman Koval

As feelings of isolation grow increasingly profound in our society, it seems logical that we would bifurcate our psyche in an effort to keep ourselves company. Julian Jaynes, an American psychologist, proposed that the human race began with what he called a bicameral mentality, where our inner monologue was believed to be the voice of external gods making commands. There was no self-reflection, no ability to perform executive ego functions, such as deliberate mind-wandering and conscious introspection. British philologist Arthur William Hope Adkins believed that ancient Greek civilization developed ego-centered psychology as an adaptation to living in city-states. Could it be possible that the development of those city-states into supermetropolises infinitely connected by social media might effectively bend the arc of our psychological universe back toward bicameralism? Might Narcissus look so deeply in the mirror that he would eventually forget its existence?

Volta Collective’s Loneliness Triptych comprises three acts and an epilogue, directed and choreographed by Mamie Green, with a live, original score by Dylan Fujioka. When the house doors open, the stage is occupied by a rotating, black office chair, a folding chair, a small area rug, and an inflatable mattress propped against the wall. The first act, titled “Doppelganger,” begins with two women played by Bella Allen and Anne Kim. They are dressed identically in white tanks and black pants. One lies down on the rug so that the other can roll her up like a fresh corpse. Our narrator, Raven Scott, watches from above, the twin dancers serving as stand-ins for her allegory’s rotating cast of characters. She walks down the stairs to a mysteriously ambient symphony of bells, strings, and keys recounting her experience with cinema escapism—a coping mechanism for loneliness so firmly tied to the 20th century that you could almost feel nostalgic for it. She speculates on whether movies might actually be able to watch us back and celebrates the cyclical nature of time captured on reels of celluloid. The dancers start this act as a duet while our narrator tells their story. By the end, our narrator becomes integrated into the dance, the divide between subject and objects dissolves, forming endless constellations of triplets.

From the red velvet seats of the movie theater, we’re thrust into the 21st century with “Camgirl,” the second act, written by Lily Lady and played by themself and Mandolin Burns. Sonically, it feels as though we’re in a yoga studio and our heroes aren’t dressed identically, but their shared vibe is equal parts casual and sexy. They walk toward each other from opposite corners of the stage and meet in the center with the inflatable mattress. Lady rolls like a log across the mattress, mirroring the opening of the first act with the rug. Our camgirl doesn’t need a camera. Its existence is as inherent as the audience they can scarcely see behind the stage lights. In Ways of Seeing, John Berger wrote: “A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father, she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking or weeping.” Lady claims that they’ll do anything to avoid pain as their alter ego supports them through endless bouts of self-pity. The two embrace from either side of the mattress, and move together as a trio that is only two-thirds human. The mattress slowly deflates until the two melt into an embrace on the floor. The lights go red and the music gets industrial. Our dancers skip together across the stage; Burn fires on all cylinders in a solo dance that ends with her wrapping the deflated mattress around her body like a dress while Lady watches and contemplates a “form of introspection that ceases to be disaffected and self-indulgent.”

Act three, “The Kid,” eschews the text, pulling us into a pure movement experience with the office chair performed by Ryan Green and Ryley Polak. Practically indistinguishable in size and shape, they form a twisted counterbalance on the chair as it spins slowly centerstage. I’m reminded of how difficult it is to truly carry the full weight of oneself—to be solely responsible for the consequences of one’s existence. They are like the opposing forces of the id and superego, constantly keeping one another in check. The inertia of their movement echoes the chaotic percussion of dissonant, grungy drums and electronic glitching. Supporting one another through inversions and barrelling leaps through the air, their dance is an endless chain reaction of ever-impressive acrobatics. Suddenly, they are bathed in an ethereal overhead spotlight, and their spinning turns to melting. They’re like cogs propelling one another with teeth turning on opposite planes. Unlike the previous acts, their ending feels quietly triumphant.

The epilogue is populated by all of the dancers at once. The New Theater stage can hardly contain all seven of them, and yet each feels just as lonely as ever. Our cast is a mix of trained dancers and actors who know how to move. However, they don’t feel mismatched as mirrors. Their talents are perfectly complementary and masterfully executed. Green’s trademark, multidisciplinary approach to theater has found its most subtle balance in Loneliness Triptych. Her players embody their characters while allowing the text, music, and choreography to inform their lived experiences. They film themselves as they vape and exchange props to a remix of Justin Timberlake’s “Cry Me a River,” a turn-of-the-century ballad about refusing to forgive. We’re left to wonder if the source of our loneliness isn’t simply a product of our elective, disaffected self-indulgence. If we do not, indeed, prefer it.

Vaginal Davis’s Magnificent Product Chronicles Five Decades of Her Playful Defiance @ MoMA PS1

Magnificent Production by Vaginal Davis, MoMA PS1, 2025. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

text and photographs by Isabella Bernabeo

Magnificent Product marks Vaginal Davis’s first major US institutional show, presenting art from her early Los Angeles projects to her more recent Berlin-based creations. Organized thematically instead of chronologically, the works take viewers on a journey filled with vivid colors, humor, and emotion.

Magnificent Production by Vaginal Davis, MoMA PS1, 2025. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

The exhibition begins in a light mint-green room titled Naked on my Ozgod: Fausthaus – Anal Deep Throat. This square room features green sheer curtains along every wall, with hundreds of photos from Davis’s early Los Angeles years covering the walls behind the fabric. Visitors are invited to slowly peel away the fabric from the wall to get an intimate view into Davis’s personal life before seducing them into the next room. This section is inspired by one of her first art exhibitions, originally held at the Pio Pico Library in Los Angeles.

In the next space, HAG, Davis reconstructs her old Sunset Boulevard apartment in Los Angeles, the site where she produced many iconic zines, such as Shrimp, Yes, Ms. Davis, and Sucker. The dimly lit room glows pink and includes a walk-in box in the center. Inside, its walls display drawings and figurines of a woman’s head, possibly self-portraits. The slanted floor creates a warped, unbalanced environment that meshes reality with fantasy, just like the work it supports.

Magnificent Production by Vaginal Davis, MoMA PS1, 2025. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

Another engaging room in Davis’s collection is HOFPFISTEREI, where visitors are encouraged to interact with her artwork. A table and four chairs occupy the room’s center, surrounded by piles of Davis’s zines, writings, and creations. A photocopier stands nearby for visitors to print out copies to take home.

Davis also utilizes a screening room, which resembles the Cinerama Dome movie theater that operated on Sunset Boulevard from 1963 until 2021. Here you can watch low-fi videos she created during the 1980s, showcasing her range of personas as an artist, queer activist, self-proclaimed “Blacktress,” and more. These recordings, much like the earlier photos, give visitors a detailed and in-depth view into Davis’s life; they’re a testament to how interconnected her art is with her identity.

Magnificent Production by Vaginal Davis, MoMA PS1, 2025. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

Another striking installment is from her Wicked Pavilion collection, displaying a reimagined version of Davis’s teenage bedroom. However, instead of her in the rotating bed, a large phallic sculpture sits in the space. The room is completely pink, from the walls to the rug to the curtains. A miniature desk sits in the right corner, topped with two lamps, a pile of jewelry, and an array of colored nail polish, hinting that Davis’s has relished dressing up as the showstopper she is since her youth.

Along the ceiling, dozens of images are hung from a clothesline. These photos are of Davis’s muses, such as actor Michael Pitt or actress Isabella Rossellini. While visitors take a look around the bedroom, they listen to a mix of the song, “A Love Like Ours,” from the 1944 film Two Girls and a Sailor, interviews that Davis herself conducted for LA Weekly in 1996, and a voice message from Davis’s own secret admirer, creating a fully-immersive experience.

Magnificent Production by Vaginal Davis, MoMA PS1, 2025. Photo: Isabella Bernabeo.

Across all of these works, Davis’s playfulness and defiance shine through. Magnificent Product is a living experience that can be overwhelming at times, yet each room offers a sense of freedom. Davis commands her viewers’ attention—and she intends it that way.

Magnificent Product is on view through March 2 @ MoMA PS1 22-25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, Queens

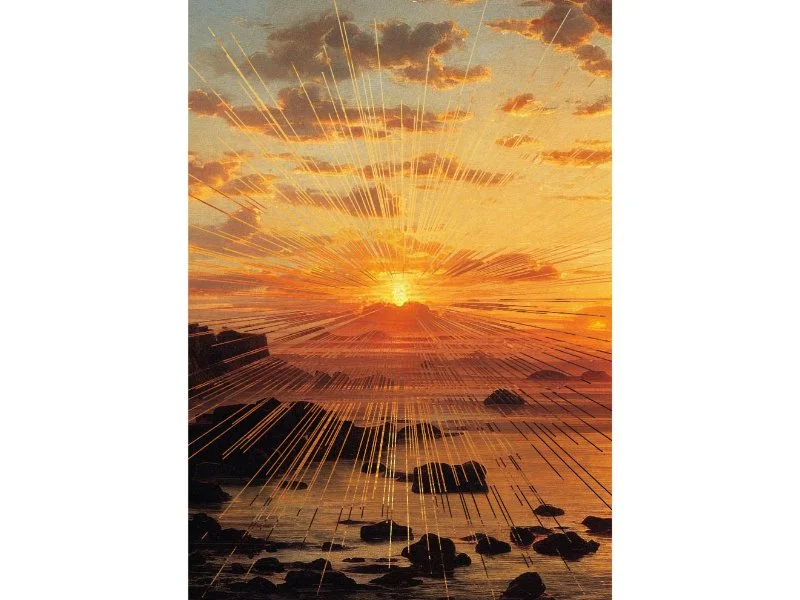

Read an Interview of Mariko Mori, the Japanese Artist Redefining Light, Time, and Spirituality →

Mariko Mori: Radiance at Sean Kelly, New York, October 31 – December 20, 2025, Photography: Jason Wyche, Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

interview by Alper Kurtul

Tokyo’s energy, New York’s boundless creativity, and Miyako Island’s quiet, almost womb-like protective nature. Japanese artist Mariko Mori redefines light, time, and space as she moves between these different worlds. Her latest project, Radiance, brings together ancient stone spirituality and advanced technology to make the invisible visible. Her self-designed home, Yuputira, which she dedicates to the sun god, is not merely a living space for her; it is the architecture of becoming one with nature. Ahead of her upcoming retrospective, Mori shares with us both the source of her creativity and the enduring meaning of silence in the contemporary world. Read more.

In Dialogue with the Present: Read An Interview of Designer Ying Gao →

All Mirrors Collection. Photography by Malina Corpadean.

What happens when couture meets code? Montréal-based fashion designer Ying Gao is recognized for consistently pushing the boundaries of fashion through her exploration of fabric manipulation, interactivity, and technology. The use of unconventional materials to make wearable art is prominent in her work, as evidenced in her All Mirrors 2024 collection, made of soft mirrors and 18-karat gold finishing. In 2023, her In Camera collection experimented with reactivity in fashion design by coming to life when photographed. Even as early as 2017, she made waves with interactive fingerprint technology that only recognizes strangers in her Possible Tomorrows collection. The infusion of technology in her work adds a sense of movement and interaction that captivates audiences, and each collection has a special story to tell. Read more

Read An Interview of Abbey Meaker on Her New Book of Photography "MOTHERHOUSE" →

In the summer of 2012, I visited the decommissioned St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Burlington, Vermont, with the polymathic visual artist and writer Abbey Meaker for the first and only time, to bear witness to her documenting the space. Upon entering, I knew nothing of the premises or its history, except that it was the former residence of her grandfather and great-uncle, whom she had never known. The air had an inexplicable weight to it, as though it were filled with lead particulates, and it felt like my heart was being held in a vice. I later read numerous violent testimonies from the children who lived there and about those who were disappeared, like Abbey’s great uncle. We also visited the nearby Mount Saint Mary’s Convent, which had a wholly inverse energy. Its private chapel bathed in natural light felt like an ebullient sanctuary. Still, what connected the two spaces, which had undergone minimal modifications since the late 1800s, were the former living quarters in each. A haunting chiaroscuro was created by the sunlight’s dauntless efforts to break through the shutters, curtains, and blinds that covered each window, all of which remained after the buildings had become inoperative and left in dire states of disrepair. Thirteen years later, Meaker has curated the resulting images into a book of photographs called MOTHERHOUSE that serves as an uncannily vivid portrait of what it felt like to occupy these illusory spaces. Read more.

Autre Magazine FW25 "Work In Progress" Celebration & Panel Talk with Caltech Astrophysicists @ l.a.Eyeworks

Last night, at the expansive new l.a.Eyeworks campus in Los Angeles, Autre magazine invited guests on a journey through space and time to celebrate its FW25 “Work in Progress” issue. The evening opened with a captivating panel featuring Caltech astrophysicists Katherine de Kleer, Cameron Hummels, and Mike Brown, moderated by Autre’s managing editor Summer Bowie, who guided a conversation spanning black holes, dark matter, and the possibility of life beyond Earth. The discussion gave way to an intimate cocktail soirée, where guests mingled under the stars with drinks courtesy of Madre Mezcal. photographs by Oliver Kupper

Order Autre #21 FW25 The Work In Progress Issue →

Click here to preorder