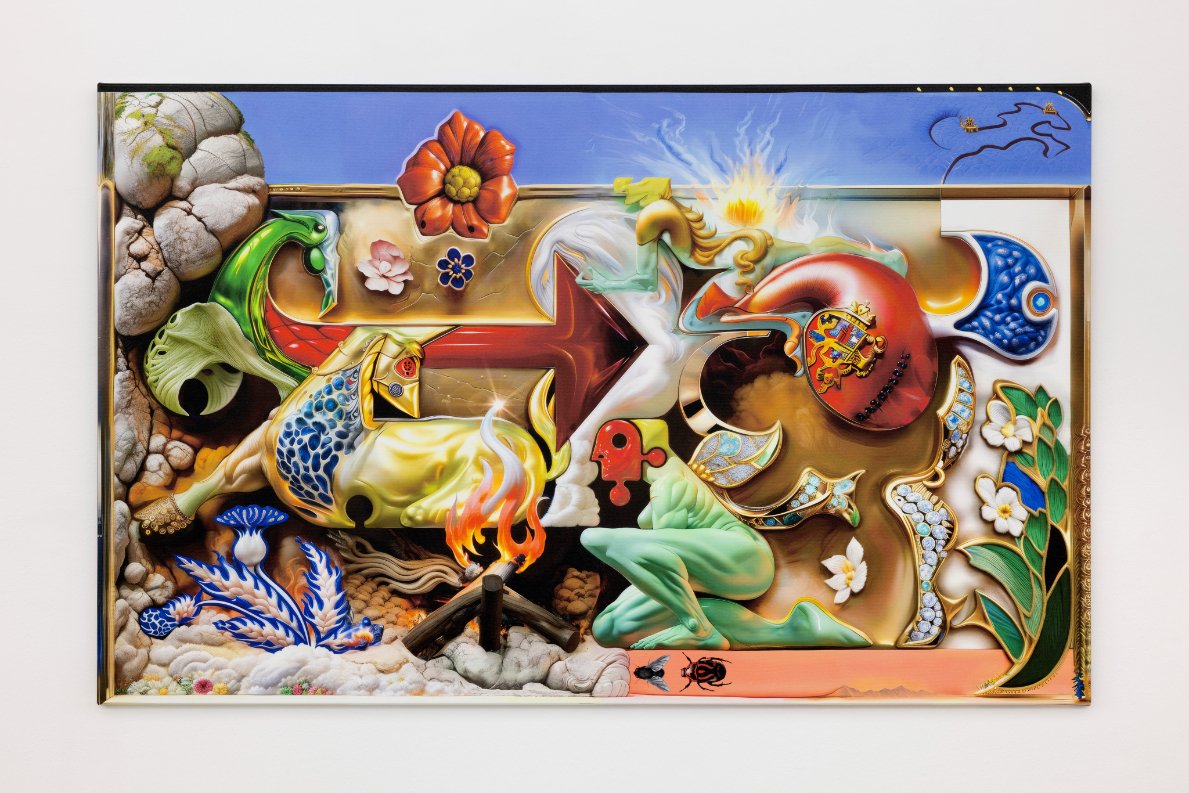

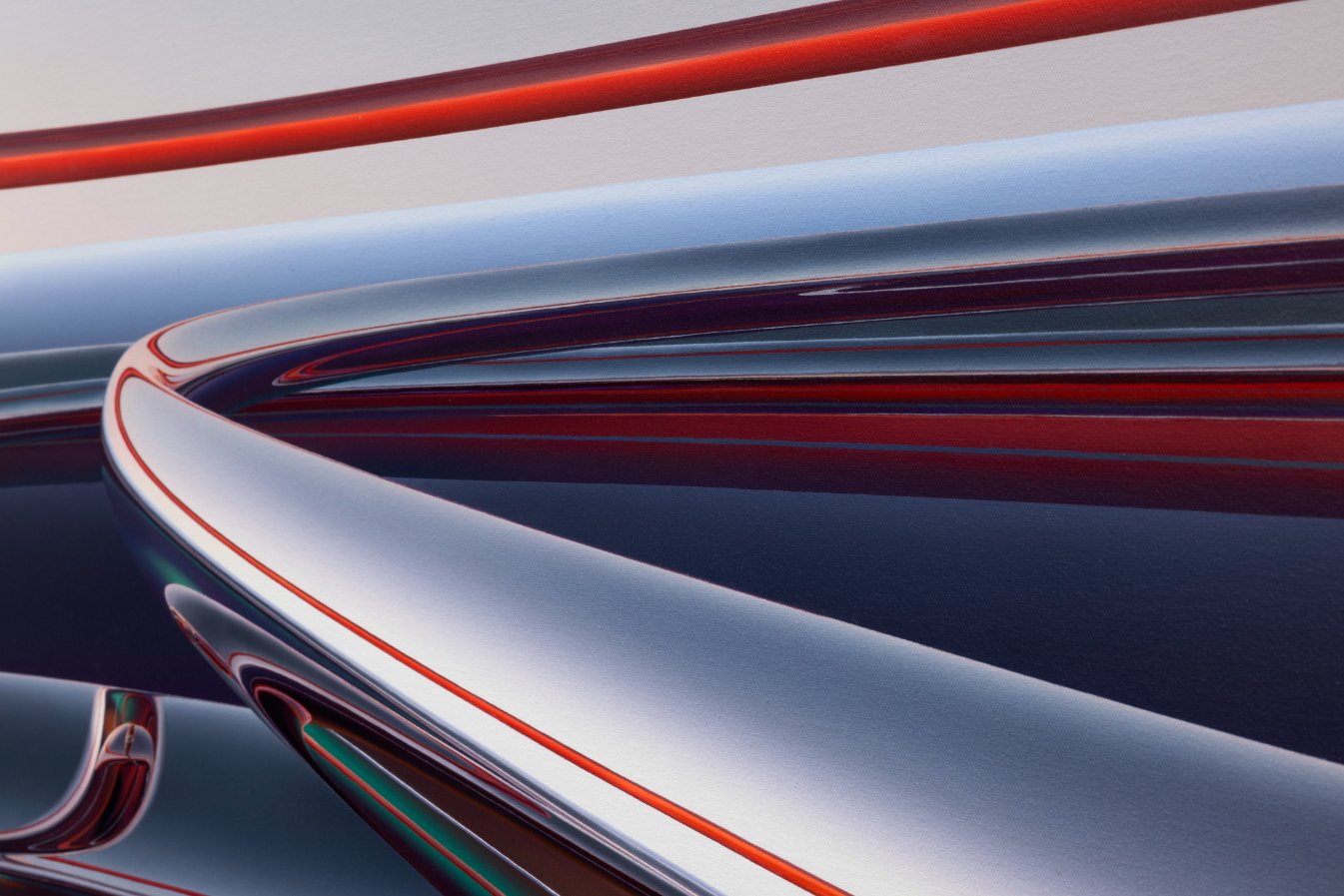

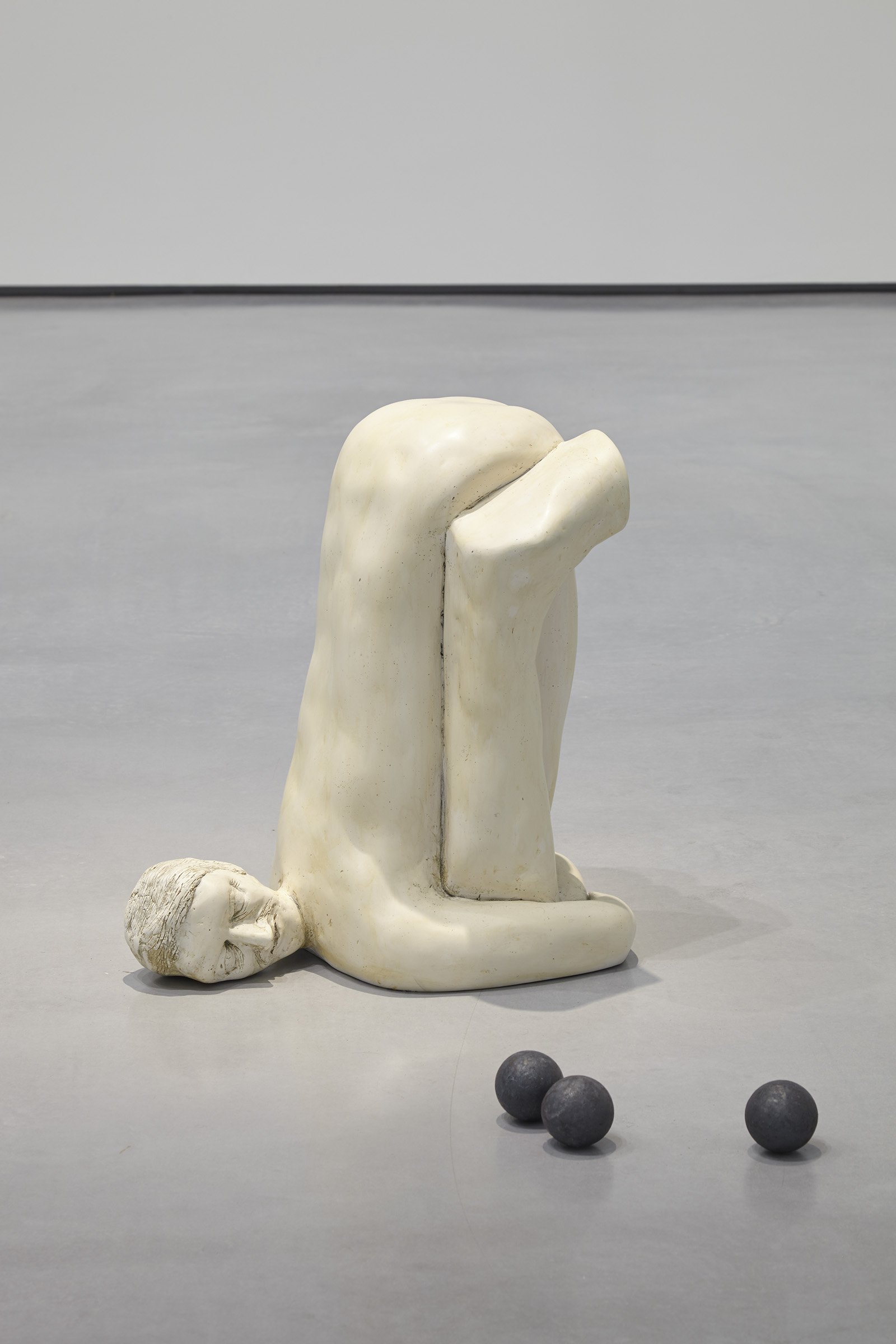

Destroyed Men Come and Go is devoted to the sculptural practice of London-based Italian artist Enrico David, who works in sculpture, painting, textiles, and installation, with drawing being key to his exploration of form. Mining a space between figuration and abstraction, David returns to the body as a point of departure, exploring the human figure as a metaphor for transformation. His interest in British and European modern sculpture has shaped his work, taking inspiration from the likes of Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti, while, at the same time, retaining an idiosyncratic aesthetic and provocatively ambiguous language. Made from bronze, silkscreen, steel, and plaster polymer, David’s human figures assume various poses, often entering a dialogue with the architecture that surrounds them – hugging the floor, leaning against walls, or being suspended from the ceiling.

Through references to anatomy, metamorphosis permeates their forms and connects these works with nature. This continuous morphing is further mirrored in David’s manipulation of materials, with modeling and casting obscuring any clear understanding of their material origin. Taken from a quote of Maurice Blanchot, the exhibition’s title elaborates on the relation of existence, speech, and the void in Samuel Beckett’s momentous theater play Waiting for Godot (1952) and its allegory of the collapse of the rational mind. In his Writing of the Disaster, Blanchot writes “We have fallen out of being, outside where, immobile, proceeding with a slow and even step, destroyed men come and go,” describing humanity’s fall from grace in the Anthropocene.

Conveying the struggle of adaptation of the self, David’s sculptures pick up on Blanchot’s thoughts on subjectivity and critically unfold the body’s autonomy through different stages of nonbeings and becomings. David favors time travel to connect the way the body is depicted into different states of being through various periods of global civilization – whether this is sleeping, hanging, relaxing, or decaying form. His references are deliberately naïve and broad, including nods towards the Maya culture, the Tang Dynasty, or the Wiener Werkstätte. However, David’s appropriations are recontextualized to focus on their formal and universal qualities, in which dysmorphic shapes, created, for example, by photographic documentation, offer new opportunities for human and non-human figuration.