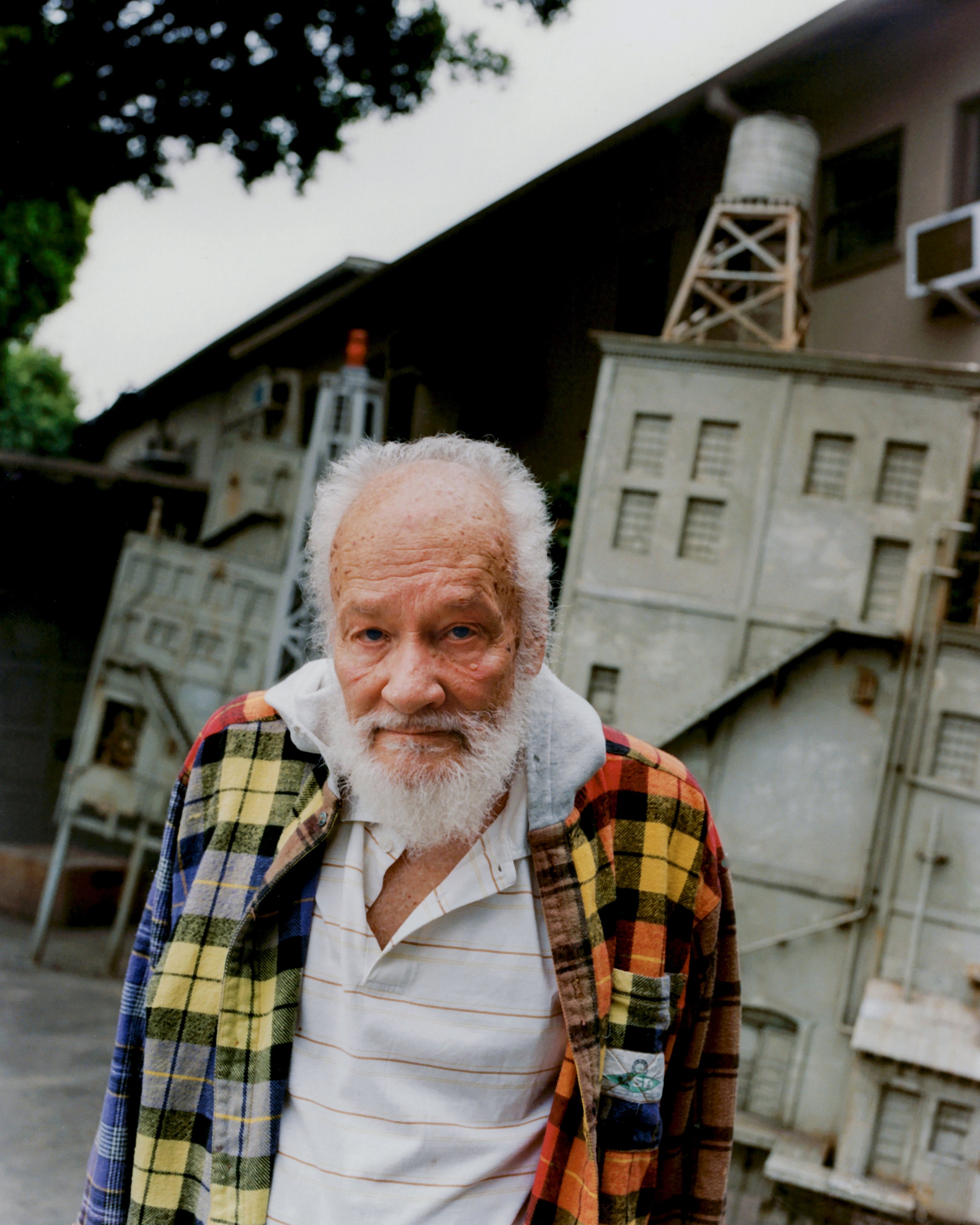

interview by Oliver Kupper

portraits by Pat Martin

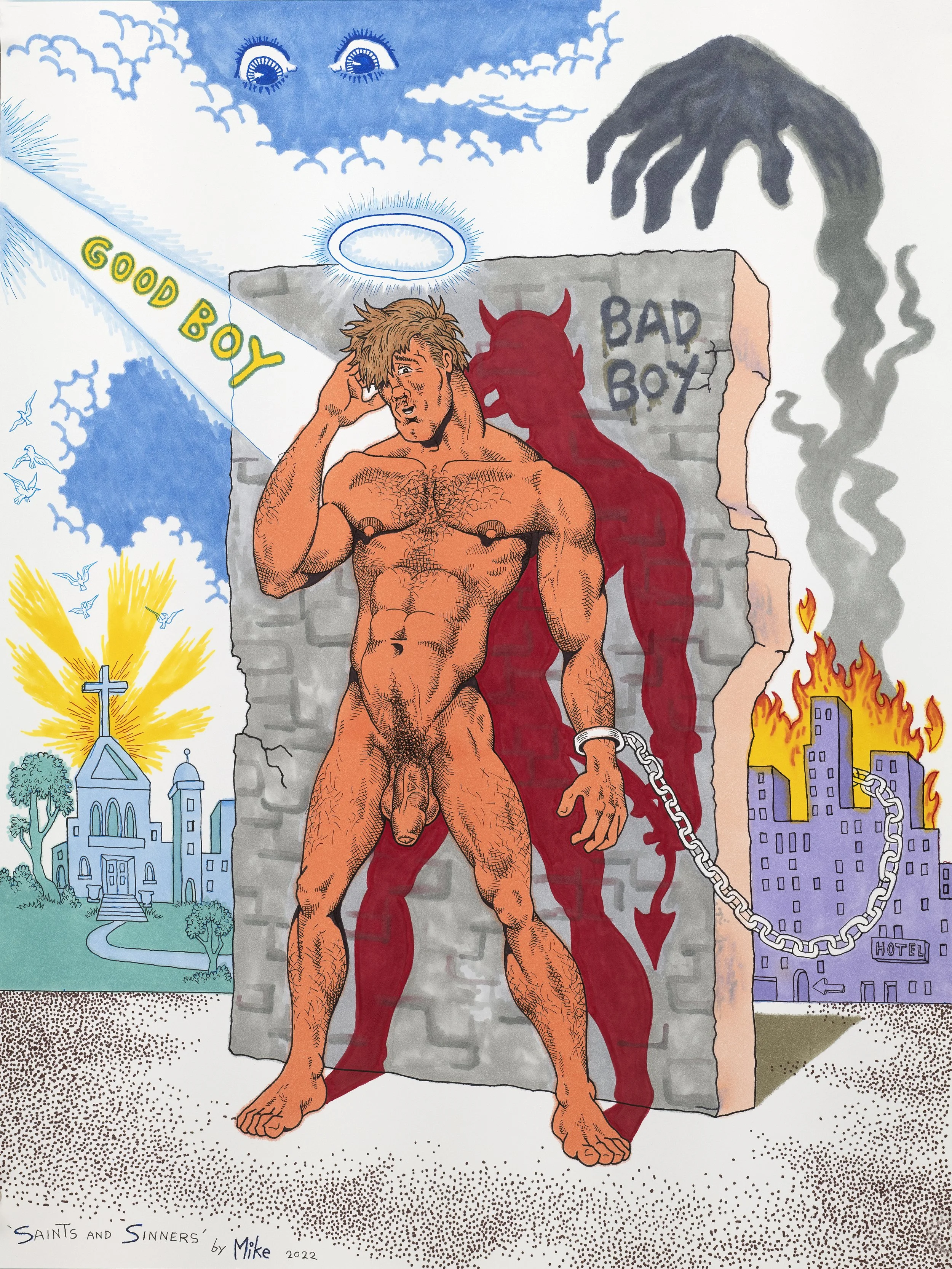

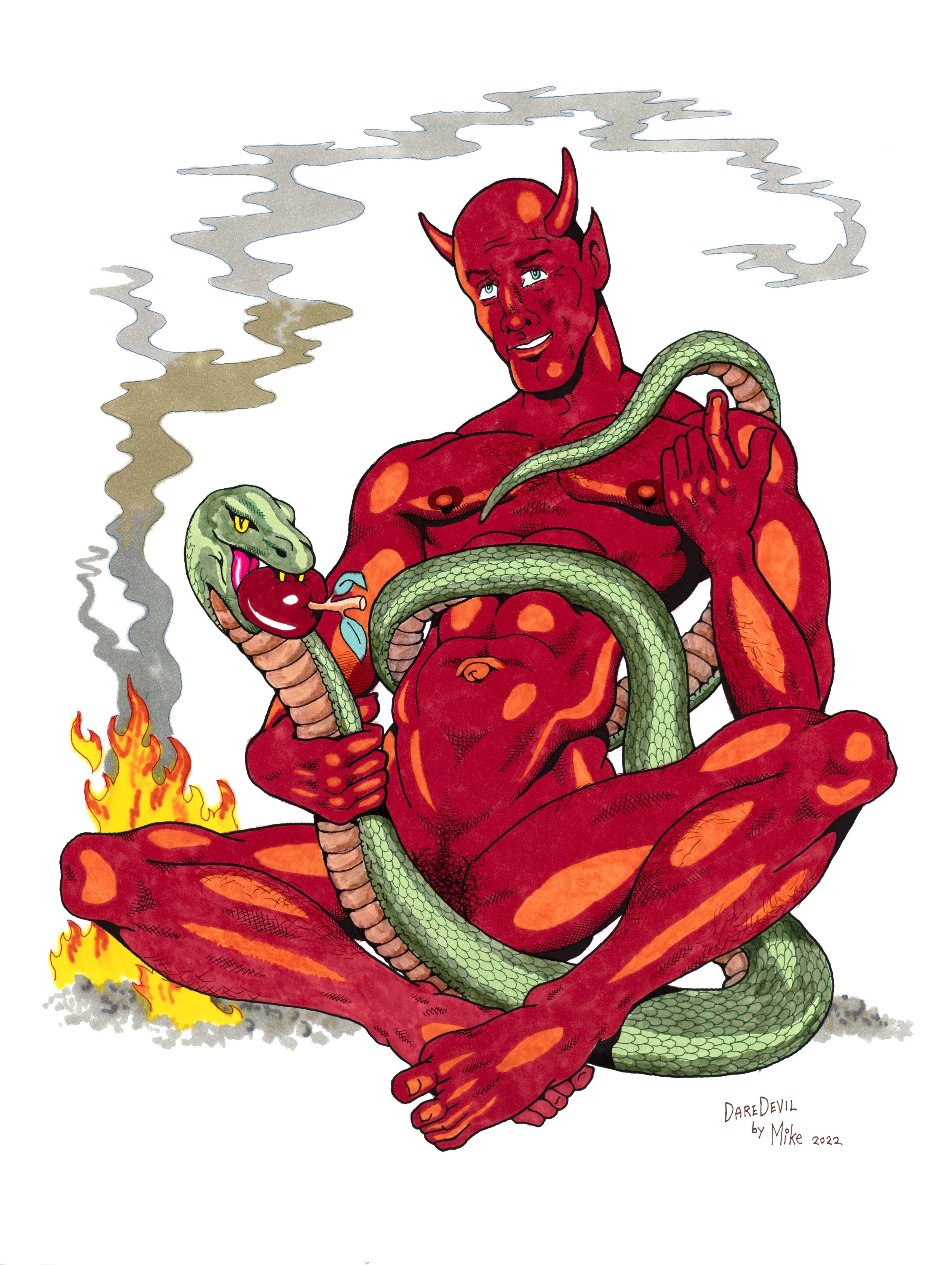

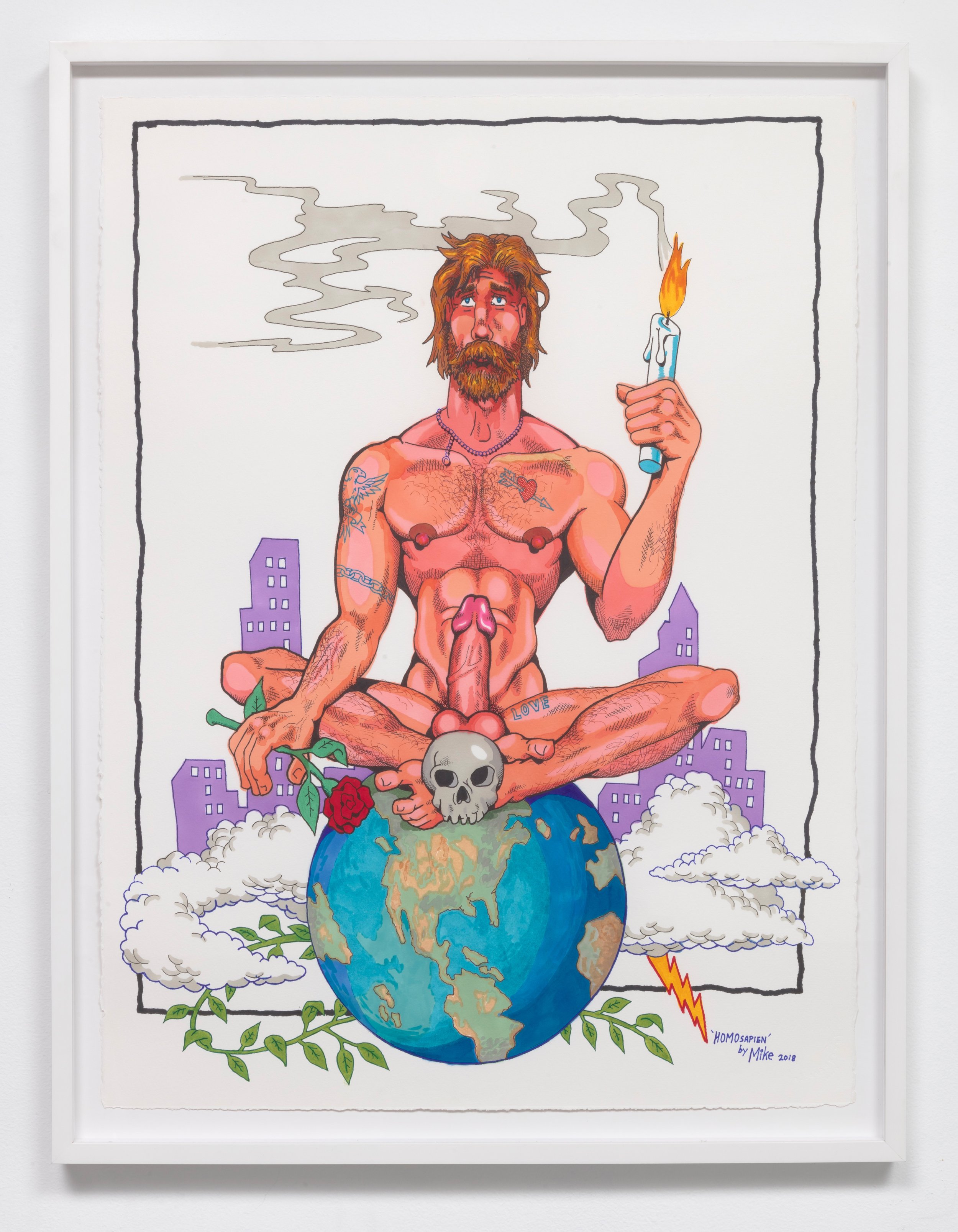

New York City in the 1960s was the cradle of underground cinema. Daring experimentations in celluloid were being made in the makeshift laboratories of urban lofts, on the streets, and on the water tower-dotted rooftops. Twin brothers, Mike and George Kuchar, were at the forefront of this movement, alongside Ken Jacobs, Maya Deren, Jack Smith, Jonas Mekas, and more. To support his filmmaking efforts, Mike Kuchar worked in the commercial art field and created erotic illustrations for the pages and covers of magazines such as Gay Heart Throbs, Meatmen, and First Hand Magazine. His drawings are drenched in hyper-saturated colors with flesh-toned muscle men in homoerotic scenes of science-fiction and Biblical epics. Today, he is still making films and drawings—many of which were shown alongside historical work during an exhibition, Big, Bad Boys, at François Ghebaly gallery in Los Angeles during the summer of 2023.

OLIVER KUPPER When did your films and paintings enter this very libidinous place?

MIKE KUCHAR It’s always been there. The urges, the drives, the desires—they’re inside me, they’re inside all of us. But, since I’m interested in playing around with mediums, I use them to express the drives, to get it out of me, and to reveal it; hopefully in a way that’s entertaining or captivating. Those libidinous drives are often the subject of the creation. It’s being taken out of oneself and put on the paper, or the silver screen, and presented to the outside world in a way that will hopefully be digestible, and in some ways entertaining. Using the gimmicks and language of the medium, whether it be paint or the camera, it’s materializing the urges.

KUPPER It’s very instinctual.

KUCHAR Putting it into a tangible form to be reviewed and experienced and told, but in a way where you stand back and look at it, to either be horrified or find it hilarious.

KUPPER Or turned on. (laughs) When did you first discover this libidinous side of yourself? Were you scared of it or did you feel liberated?

KUCHAR It had to come out. You can’t stop it. It’s there and it only gets stronger with age because the hormones are getting more fierce. It depends on who you’re working with or what interests you at the time. But, there are a thousand inspirations.

KUPPER Your first films were made in your Bronx childhood apartment at around eleven and twelve years old with your twin brother [George]. What did your parents think of this? Were they supportive of these cinematic experimentations?

KUCHAR They were domestic-minded folks. They just let us do what we wanted to do. Oh, actually, my mother kind of complained. We would sometimes use the bedspreads, or the coverings from the sofas as costumes and go up on the roof to shoot these kinds of Biblical epics. She would find out and get very mad. I remember she would go on a tirade. So, that was the only way she recognized interest in our movies; when we sort of disrupted the draperies in the apartment. But otherwise, they didn’t care. My father liked our movies—he was only interested in our movies because he liked some of the girls we had in the pictures. He’d sometimes ask if we could take some private pictures of them, but I wasn’t interested in doing that.

KUPPER Was there religion in the home? Because there are a lot of Biblical references in your work. Did you go to church?

KUCHAR Yes, we were religious. Our family always wanted us to go to church, but we didn’t go. My brother was more affected by the church, mostly attitude toward life and sex, and dealt with them in his movies. Sometimes, they’d border on sacrilege. He had a battle. But what affected me—I just liked the Biblical movies. I like them because of the costumes and sets. For me, going to church was a rather strange experience. It was really a temple full of masochistic imagery of suffering, and martyrs, and people chained, or nailed to things, like Saint Sebastian and Christ. It was such a strange mixture of sadness and eroticism.

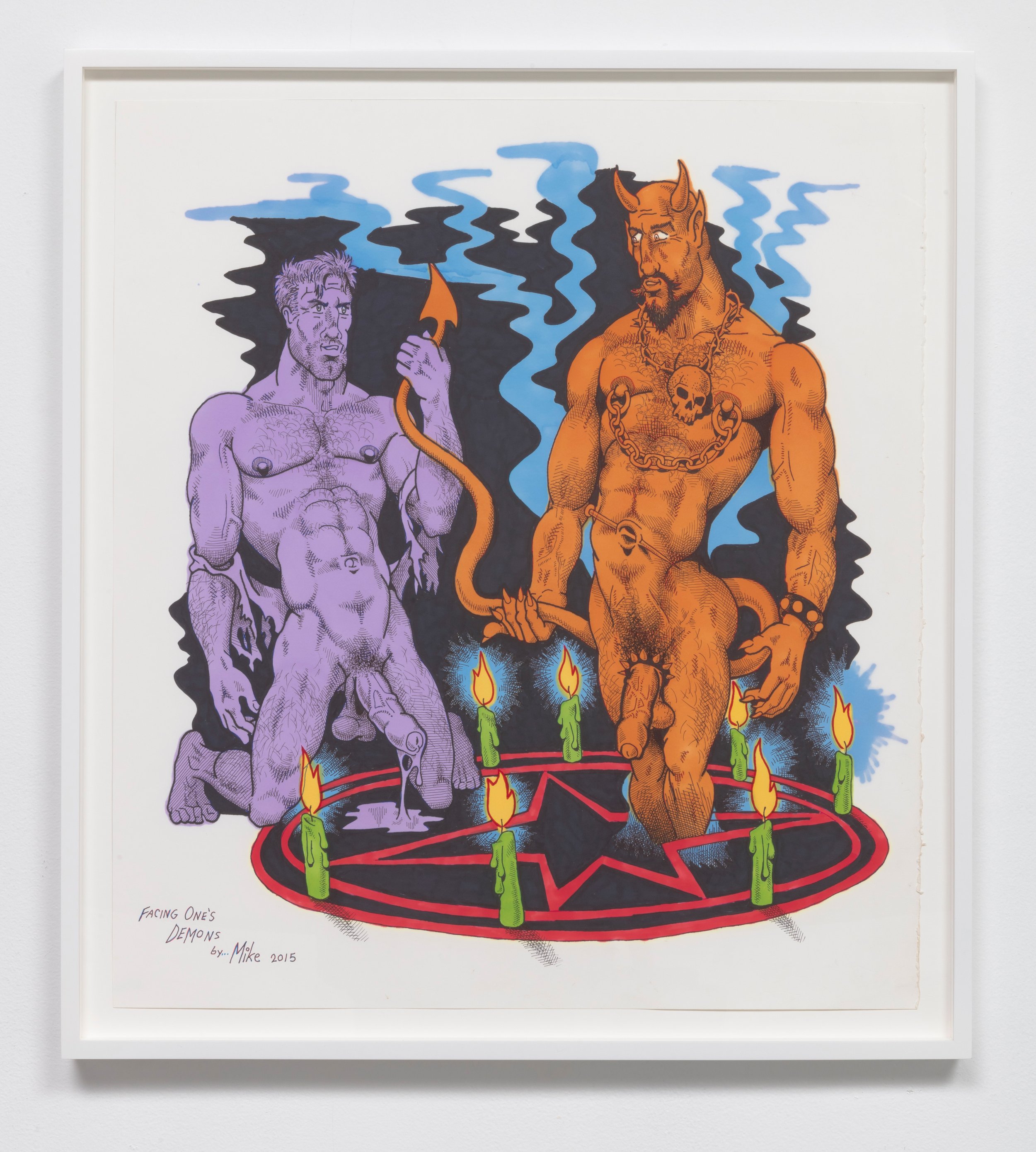

Mike Kuchar, Facing One’s Demons, 2015

Ink and Marker on paper

24.5 x 22 inches; 62 x 56 cm

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles

KUPPER It’s sort of what happens when you suppress these libidinal instincts.

KUCHAR Yeah, it didn’t give me any guilt, though. It had a kind of haunting ambiance. My brother was more affected by guilt and salvation, and he had to deal with that and he did so in an often-entertaining and relevant way.

KUPPER When you were making movies together, what was the creative process like?

KUCHAR In the beginning, it was an activity, it was a sport. We’d get together, hold a party, and instead of putting on the record player and dancing, we were gonna make a movie. And everybody knew it. And we were all there to create a movie. And the people were there to act in it and to play characters. And then, when the picture was done we’d hold another party to see the finished product. As we grew older, it became something else. It was still movie-making, but it had a different process. You’d meet individuals and you’d create more controlled experiments of depicting inner drives, and inner feelings, and interpreting them into a movie. The directing was getting more internal and precise.

KUPPER Did you and your brother share a twin language?

KUCHAR No, the only thing we shared was equipment. He made his type of movie and I made mine. We were twins, but we actually had different temperaments. And then, of course, after we made the movies we’d show them to each other.

KUPPER Can you talk about how instinct has driven your creative pursuits?

KUCHAR Sometimes, the basic reason we create is not flattering. But what’s created from that urge grows bigger into something else, or at least that’s what you should aim for. It will begin to encompass something even greater, or something more important than the fundamental reason—just a basic kind of mood. A need. A basic need.

Sometimes how I start making a movie is like being on a psychiatrist's couch. There are reasons why you place people in a certain way, and why you dress them in a certain way. And then, you begin to realize and analyze where it’s going. Very seldom have I made pictures where I don’t know the end. And a lot of times it has to do with the people you’re dealing with, or your feelings towards those people, which we then turn into a kind of bigger story, and then that begins to build into the structure of the picture.

KUPPER I’m curious about how the underground movies of that time were brought above ground. Jonas Mekas was a big part of this process in New York. Where did you show your movies? How did Jonas discover your work? How did you meet him?

KUCHAR There was a girl that we went to school with, it was in a poetry class. She said, “I know an older painter, let’s go over to his house, or I’ll tell him to come over, and we’ll make a movie.” So, we met this older painter and he said there’s something going on at a loft in lower Manhattan every month. Sculptors and painters would get together and show movies at night. This older guy said, “Why don’t we take your pictures and show some of the movies you made.” It was Ken Jacobs’ loft. They got a kick out of the movies. Ken Jacobs said, “Look, next month, come back and bring more of your movies. I’m gonna invite some other people.” He invited Jonas Mekas, who was writing articles about this underground film movement in The Village Voice. So, Jonas Mekas came, and he saw our movies, and he enjoyed them very much. He said that he opened an underground theater in New York and that they’d like to show them there. So, Mekas wrote a great review in his column in The Village Voice and showed our movies at his theater.

KUPPER What were the first movies that you shared there?

KUCHAR Pussy on a Hot Tin Roof (short, 1963), A Town Called Tempest (short, 1963), Born Of The Wind (short, 1962)…all done in 8mm.

KUPPER And this was shortly before your first 16mm film?

KUCHAR This was before, yeah. I found out about 16mm from other people in the underground, from seeing the others who were beginning to buy 16mm cameras. I got a bonus from a job, it was $250, I bought a Bolex. So, we upgraded our cameras to a bigger format.

KUPPER And that was from doing illustrations in magazines?

KUCHAR I had a job for a while in the commercial art field. I used to do photo retouching. I never went to college, but I went to a commercial high school. There were two art schools in Manhattan: High School of Music & Art, which was fine art, and The School of Industrial Art, which was commercial art. A teacher said to go to the latter because fine art is always tough in the beginning. So, I went to the commercial school, graduated with a portfolio, and ended up doing photo retouching in Harper’s Bazaar—with actual transparencies and dyes. It paid well, but I was never interested in it, so I couldn’t adapt to it. I was always a misfit within corporations.

KUPPER Kenneth Anger passed away a few days ago…have you ever crossed paths?

KUCHAR My brother knew him better than I did. They would get together during shows. I met him once in London. I happened to be in London to visit a distributor to see if there were any royalties for me and Kenneth Anger happened to be there doing the same thing. He came up and said, “Oh Kuchar, we finally meet!” And that was my only encounter with him.

KUPPER There was a moment when he was in San Francisco with the Church of Satan and that whole crowd. You were in New York, but your brother was in San Francisco a lot earlier.

KUCHAR I’d go back and forth. I was sort of a drifter and always had certain obligations. Eventually, I began to permanently live in San Francisco. But my brother was pretty well stationed there at the San Francisco Art Institute, which kept hiring him every year. He did that for thirty-five years.

KUPPER You were both making art, but your drawings came earlier…can you remember your first drawing?

KUCHAR When I was four years old, my father gave me a cigarette—he also wanted to know if I was interested in whiskey. I tried that and thought it was horrible. But one afternoon, he came in with a pencil and paper, and said, “Why don’t you draw us something.” And I remember the drawing I did: it was a stick figure with a hat. I was such a young child, but it seemed to be an omen of what I’d be interested in. I always admired comic book artists and I wondered if I could even come halfway close, so there was a certain urge in me to strive to draw something, even slightly close, like how they did it. So, I began to draw. But then, a freaky thing happened. Some guy was publishing a comic book and they needed someone to make drawings. This woman I knew recommended me. I gave a sample and they flipped over it. All of a sudden I had an assignment that would also give me a little money. So, that got me focusing on my drawing. My interest was now focused because I had to actually produce something. And then, it escalated—the comic book became successful for that publisher, so he kept asking me to do more. Then it got out in the world, and other publishers saw my work, and they somehow managed to contact me. The homoerotic became my specialty. It was no problem for me (laughs). I knew the subject quite well. I looked at drawing like my second career. And that’s what I became known for. I did get fan mail! And I’d get phone calls from strangers with heavy breathing…It was like voodoo. I would get these calls late at night and it was all because of the drawings. The drawings were haunting people.

KUPPER When did color come into the work? Because in the ’60s and ’70s, it was expensive to do color in publications.

KUCHAR The color came in later with the bigger, slicker homoerotic magazines. There was one illustrator who was really something, Harry Bush. He did all these kinds of vibrant teenagers and they would print his work more in color. But earlier, there was a publication called Physique Pictorial that was mainly black and white.

KUPPER I want to bring up two things, which are artificial intelligence and the ongoing cultural war that we’re in now—there’s a renewed censorship going on with artists. One of your films, Sins of the Fleshapoids (1965), which told the story of robots in a nuclear holocaust, was extremely prescient.

KUCHAR I didn’t give any thought to that picture. I said, “Okay, so this will sort of be my robot movie.” I might’ve seen some trashy poster about robots that are mimicking people and then I said, “Okay, I’m gonna do something like that.” Maybe it was that we unknowingly do things that are really prophetic. But that film was unconscious, I just thought it would be a colorful thing to work on.

KUPPER During that time, a lot of those underground film screenings were being raided and negatives were being stolen, and people were being arrested just for showing their art.

KUCHAR That was interesting, though, because then whole court cases came up and things were settled and became more open. But there had to be court cases and they had to deal with this stuff and that opened the gates for the culture to become more lenient or acceptable, and digestible. Then these films were being shown on bigger screens at bigger theaters, and even in museums. The MoMA had a big series on the underground cinema movement. They presented it to the more refined public in institutions that were bigger and revered, and legitimized. So, it slowly seeped in and was absorbed by the movie-making culture.

KUPPER Did you deal with anything personally during that time in terms of being censored or raided?

KUCHAR No, not my brother and I. Our films were like camp-y manifestations. We made them in studios, or in apartments, with people who wanted to be actors. We were hosting the artificiality, but it was not to destroy the tradition of movie-making. It was carrying on the tradition, but then it became something else. It became grotesque, or beautifully funny.

KUPPER The one thing that sticks out are the characters’ eyebrows.

KUCHAR My brother was very interested in makeup and seeing makeup on actors. Sometimes to make the scene work you change the shape of their eyebrows—it’s like a kabuki master—to make them look sad by putting the eyebrows like that. Their faces are canvases you can paint on, especially if they are female characters. The eyebrows even made non-actors look like they were acting.

KUPPER Your show at François Ghebaly is really interesting because it mixes a lot of new and older work. What was the organization behind this curation?

KUCHAR Actually, it was up to the gallery. If they’re gonna put up money to house me, and fly me in, I said “Look, have fun.” I’m very happy they took an interest in my work. I mean, my brother and I have closets full of movies and it piles up. You can die, the landlord comes in, throws everything away, or the house can catch on fire. It’s interesting, but there are these institutions and places that somehow find worth in all the work and they wanna house it, protect it, and also make it available. It just happens.

KUPPER I think a lot of your life has been led by intuition and it got you to the right place.

KUCHAR It’s all chance. It’s because of our interest, we would just make movies no matter what. But it affected some people who thought it had worth and they wanted to preserve it.

KUPPER Do you still imagine movies you want to make?

KUCHAR I do, of course. I made one last week. They’re more minimal. I don't have the versatility to do things. I’m too old. But that changes my style. You have to adapt to what you can physically do—I call them soul-searching pictures: people talking about their existence or certain problems. I try to make them feel like they have depth in the way they’re photographed, and the words used.