Cadillac Ranchby Ant Farm (Lord, Marquez, Michels) under construction, June 19th, 1974.Amarillo, Texas. Courtesy Chip Lord

interview by Oliver Kupper

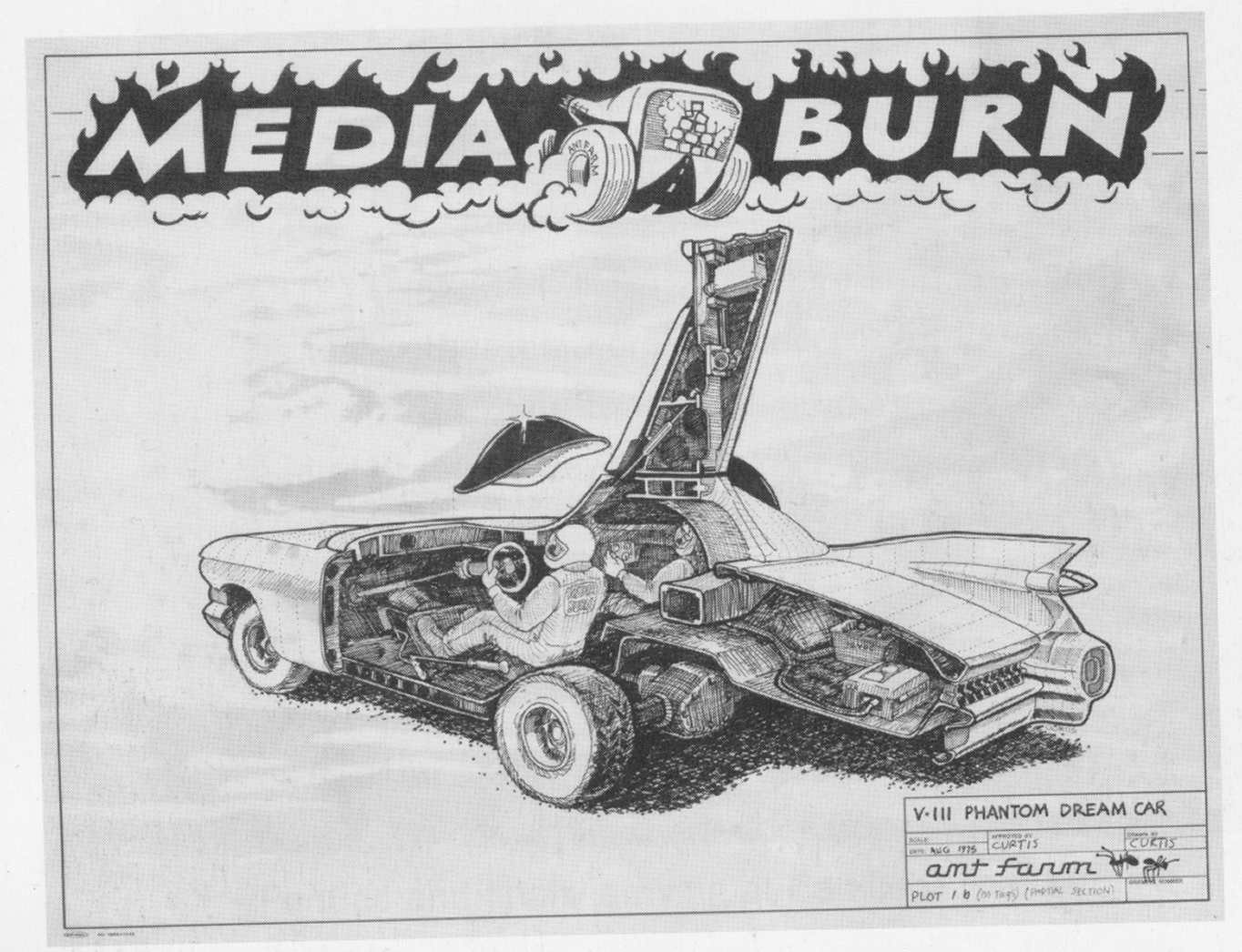

In 1975, Ant Farm—the techno-utopian multidisciplinary architecture collective founded in San Francisco by Chip Lord and Doug Michels (joined later by Hudson Marquez and Curtis Schreier)—launched a customized 1959 Cadillac, renamed the Phantom Dream Car, at full speed into a wall of flaming television sets. Media Burn was an excoriation of Post-War American popular culture, mythos, and the consumerist imagination, particularly our obsession with broadcast media. This singularly powerful act came to exemplify Ant Farm’s irreverent architectural examinations, where the blueprint was the message itself. Armed with portable videotape cameras, Ant Farm turned the gaze back on those wielding the power in a time when America was entering its mirror stage, and millions of young people were realizing the country’s intrinsic hypocrisies and instincts for violence. From its inception in 1968 to its dissolution in 1978—from the last flickering embers of the hippie love fests to the early days of disco—Ant Farm experimented with alternative modes of living with detailed cookbooks for building inflatable shelters and a Truck Stop Network for flower children searching other flower children out on the open road. Ant Farm also buried Cadillacs in the Texas sand, reenacted John F. Kennedy’s assassination, and they had plans for an embassy where humans could communicate with dolphins. In the end, a fire at their studio was a symbolic curtain closing for the underground collective whose prophetic visions of the future can be witnessed today in a digital epoch of surveillance capitalism, artificial intelligence and the twenty-four hour news cycle.

OLIVER KUPPER: I want to start off with talking about the day you kidnapped Buckminster Fuller. I think it says a lot about your generation’s fascination with his mode of utopian thinking, and it set the tone for the radical, utopian antics of Ant Farm.

CHIP LORD: The kidnapping? Well, Doug Michels [co-founder of Ant Farm] and I were teaching at the University of Houston. It was the spring semester of 1969. I don’t think Ant Farm was at all well-known at that point in time. We heard that Buckminster Fuller was coming to speak to the engineering school at the U of H, so Doug basically called Fuller’s office and said, “We’ll be coming to pick you up, and this is what we look like.” And then, he called the engineering school and said, “I’m calling from Buckminster Fuller’s office, and he won’t need a ride in from the airport.” (laughs) And so that’s what we did. We met the plane, and I think we were fumbling in my turquoise Mercury Comet. And we drove him to the campus of St. Thomas University, where there was the machine show exhibition [The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age]. And in the machine show was the Dymaxion car [1933]. At that point, he said, “Oh, I don’t want to see it, that was a bad episode.” (laughs) But we took him in anyway, and when he did see it, he was very excited. The front seat cushion, the back part had fallen, and he reached in to make a little correction, and of course, a guard came over and said, “You can’t touch the art.” And that was about it. But then, we took him over to U of H and delivered him to the engineering school.

KUPPER: Obviously, his thinking about the world was hugely inspirational, but what was it about Buckminster Fuller? Where did you learn about his ideas?

LORD: For me, it was through Whole Earth Catalog. Every issue, for several years, began by publishing something by Buckminster Fuller. I didn’t really have that personal connection to specific ideas until I started reading Whole Earth Catalog, which was a graduate education. Because a degree in architecture is not really an intellectual degree. It’s an art degree, basically, and there was no theory introduced into architecture during the 1960s.

KUPPER: What brought you to architecture?

LORD: As a high school kid, I was more interested in customizing cars and hot-rodding, but for my parents, that would not lead to a career. I also liked walking around in houses that were under construction in my neighborhood in St Petersburg, Florida. Especially when the walls had gone up, but they weren't solid yet, they were just the studs and you could walk through walls. Out of that experience, I thought, well, maybe architecture would satisfy both the creative instincts I have toward cars and yet, it’s a more professional career. I mean, that decision was made kind of at the last minute, so I went to Tulane. For an undergraduate architecture degree, you start right as a frosh, embedded in a culture that’s based around drawing and the studio, which was exciting at the time. But later, I realized I didn’t really get that much of a broad education out of going to college.

“There was a lot behind what we were doing as Ant Farm that came from the knowledge that there was a much bigger community exploring alternatives.

KUPPER You were also at the forefront of witnessing the post-war boom of the American economy—car culture, and the suburbs—which must have been fascinating.

LORD: When I was eleven, we moved from a small town in Connecticut to St. Petersburg Florida, and that was a huge transition. It was not really a subdivision, it wasn’t Levittown, but a nice, small development. Not really knowing it at the time, I was embedded in the world of advertising around the automobile in the mid-1950s, the tail fin era.

KUPPER: Politically, right around the time you started Ant Farm—the late 1960s—Kennedy was dead, modernism was proving its failures, pollution, Manson, Vietnam. There’s a lot going on. What was the ultimate epiphany that turned the youth to this kind of radicalism and distrust of the system? Can you talk a little about the sociopolitical miasma that was happening during that time?

LORD: On a personal level, of course, it was the Vietnam War; how to make a personal choice. I really didn’t want to go. I actually was in the Navy Reserve program. I was a year behind in school, and it was the only way I could finish without being drafted and losing my college deferment. But once I had graduated, more than ever, I didn't want to be drafted. So, I went to the Halprin Workshops in San Francisco in the beginning of July 1968. It was a thirty-day workshop for architects and dancers, which is a great combination, of course (laughs). There was a third leader of the Halprin Workshops in addition to Larry and Anna [Halprin], a psychologist named Dr. Paul Baum. Eventually, he wrote me a letter that got me out of going to Vietnam. But it was only a little bit later within Ant Farm where I think we started to react or create works that were reflecting some of the craziness of living through that moment.

KUPPER That craziness definitely seems like it forced Ant Farm to think about this utopian impulse, that you needed to create a better world.

LORD: Or to add to the world in some way. I mean, the Eternal Frame [1975] was a pretty strange idea, to reenact the Kennedy assassination. But you know, there was this huge interest in literature around it and all the swirling conspiracy theories. And at the same time, that decade in the seventies was such a utopian moment in the art world, and all these additional mediums were being explored. One of them was performance art, and another was video art, and they kind of came together in the Eternal Frame. Maybe there was a truth in actually reenacting it, going to Dallas and being in that place, and recreating the image of the assassination. And it was frightening, actually, to be there, to do that.

KUPPER: Marshall McLuhan also had a big influence on Ant Farm and the idea of the “medium is the message” and the “global village.” Using technology was an example of this utopian thinking as well. How did his ideas influence you?

LORD: I was a student when his book The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects [1967] had just come out. And what was interesting was that it was a collaboration with a graphic designer, Quentin Fiore. It was actually reprints of things McLuhan had written as text and more theoretical analysis about the ‘global village.’ But in The Medium Is the Massage, it was put into a visual form, and I think that really influenced me. I never saw him lecture either, but the way images were used to amplify his ideas about the global village, it was so different from the discipline of architecture. At the same time, the realization that architecture was this kind of privileged, elitist profession, that you had to have clients, and the clients had to have the money for whatever they wanted to build. So, for my generation, graduating in 1968, so many people wanted to avoid going and doing the typical architectural career.

Clean Air Podperformance by Ant Farm, U.C. Berkeley, Sproul Plaza, Earth Day, 1970(Andy Shapiro and Kelly Gloger pictured) courtesy Chip Lord

KUPPER: What was Ant Farm’s interpretation of the global village? How would you define it?

LORD: I guess as the collectivity that existed in the counterculture, because there was a lot behind what we were doing as Ant Farm that came from the knowledge that there was a much bigger community exploring alternatives. Whether it was going back to the land, living in communes, co-housing, so many different ways to reject the existing set of expectations. I think that gave us the strength to keep going, to keep experimenting, and producing the work that we did.

KUPPER: One of the most incredible works that encapsulates those ideas was Electronic Oasis [1969], and also your idea of an ‘enviro-image future.’ Because it was way ahead of anybody’s time. Can you talk about the enviro-image future?

LORD: The idea that a computer could generate environments and put you in places was part of hoping to make another psychedelic experience, without drugs, without taking LSD. It just seemed obvious that it was going to happen. It’s only now really happening with AI. There was, of course, the enviro-man, who was connected to a computer, and sitting next to him was enviro-woman, and this was just a visual stunt that was done while we were teaching at the University of Houston. But that project was about simply creating that image in order to show that it might be possible. Most of our presentational form was through the slide show and that also came from architecture. It’s a very good way to contrast and to create a narrative between the images.

KUPPER: And then there was the Truck Stop Network [1970], which is really interesting.

LORD: A lot of people at the time were either building campers on a pickup truck, or modifying the Volkswagen bus. And there was this idea within the counterculture of nomadics. So, we were conceptually and architecturally combining the idea of the truck stops that already existed as a network across the US, and making them countercultural truck stops. You would stay for a few days or a week, plug in, and each truck stop had services built in that would make it more of a community. There's access to computers, there’s daycare, there's all of the social community structures.

KUPPER: Another work that had to do with cars was Cadillac Ranch [1974], which came a little later. It was installed around the time of the oil crisis, I don’t know if that had anything to do with it?

LORD: Well it did, absolutely. It was 1973 when that actual embargo from the OAPEC (Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries) countries happened. You had to wait to get gas in California, to fill up. And so, Cadillac Ranch was conceived at that moment. It was easy to be very aware of the social hierarchy attached to the Cadillac. General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler all had multiple makes and the idea for General Motors is you might, as a young man, buy a Chevrolet and be loyal to GM, then move to Pontiac, move to Oldsmobile, Buick, and then finally in your fifties, making a good salary, you would achieve Cadillac status. The funniest thing was, we realized that our fathers, none of them ever made it to Cadillac. The furthest they made it was Oldsmobile. So, you could say we were realizing the final two steps of the social hierarchy by making Cadillac Ranch, but also putting these gas guzzlers in the ground.

KUPPER One of Ant Farm’s most iconic works that used a Cadillac was Media Burn [1975], because it wasa combination of two things, which were Kennedy and America’s fascination with television and cars. Can you talk a little bit about where that piece came from?

LORD: When we traveled in the Media Van, we went to the East Coast and met the publishers of Radical Software. There was an identifiable idea that there should be an alternative to the three major television networks, and it may be possible with portable video, which had just come out. The Sony Portapak was designed for education, schools, and businesses for producing training tapes. But artists and community activists immediately started using it as an alternative form of television and that was kind of solidified in “Guerrilla Television,” which was an issue of Radical Software. The editor, Michael Shamberg, had asked Ant Farm to design it. So, we did. We were engaged in the idea of alternative media and alternative architecture, and that became part of the idea of Media Burn. The idea was to create an image that would be powerful in its own right, but would also attack the monolith of broadcast television, which seemed to have a hold over the American public through advertising and image control. Seeing the car crash through that tower of televisions would be symbolic of an attack on that monolith. It was as simple as that. It took two years to realize that one image, and in that time of the planning, other meanings expanded out of it, and it ended up being a huge community effort. But we had to have a speaker, a politician, hopefully. And that is where the conceptualization of using a Kennedy impersonator as a speaker at Media Burn came in, and it was just a short jump to “Well, if we’ve got Kennedy, we might as well reenact his assassination.” And that was Eternal Frame.

KUPPER: That also connects to a little bit of your personal work later with Abscam [1981], the recreation of surveillance footage; a statement on the power of these images of Kennedy’s assassination. Nobody, at that point, had ever really seen anything like that before. It really speaks to our voyeurism and thirst for seeing this kind of violence.

LORD: And also, taking control of it too, because it was such powerful imagery that made the viewer almost powerless in the face of it. So, could we take control of it in some way?

KUPPER: In 1978, your studio burned down. Why was that the official end of Ant Farm?

LORD: Well, at this point in time, Ant Farm had become a three-person partnership, Doug Michels, myself, and Curtis Schreier. Doug Michels wanted to move to Australia to develop the Dolphin Embassy. Curtis and I were not interested in moving to Australia. There was a woman involved and Doug wanted to go back to see her. I think in '76, there was a period of time when he was not present, and the studio space had become kind of just Curtis and me showing up, but it felt empty and people would often knock on the door asking, “Is this the Ant Farm?” (laughs) We would give them the little tours, but it had become almost a museum of itself in a way. It was over as a working partnership, and then the fire was a symbolic ending and almost exactly ten years after the founding, in 1968. So, that seemed appropriate, to have such a spectacular ending.

KUPPER After Ant Farm disbanded, how do you think your utopian thinking changed? I mean, there’s that incredible piece you did called American Utopia [2020]. Do you think that your view of the system became more cynical after Ant Farm?

LORD: There was certainly a cynicism within Ant Farm, I must say (laughs). No, for me, it was like, Well now how am I going to make a living? It was a different era, the counterculture wasn’t dominant. A lot of people in counterculture had opened businesses, natural food businesses, and other things. Not everyone, some people had successfully lived off of the land, but everybody had to confront, “how do you make a living, how do you survive?” I tried different things, like freelance photographer, and writer, having a contact at New West magazine, but you know, that was never going to pay the bills. So, I thought maybe teaching was going to be a collaborative venture, which was an aspect of Ant Farm. So, I applied for a job at UC San Diego in the visual arts department. The irony was that the work of Ant Farm was my credential, and there weren’t that many art departments where it would actually be effective (laughs).

KUPPER: What do you think now, post-pandemic in this weird political climate we’re in—what would Ant Farm be exploring now?

LORD: (laughs) It’s funny because that question was also asked at the end of a lecture, and I turned it on the room full of students. I said, “It’s really up to you, the next generation, to make that utopian gesture.” So, I don’t really have a good answer to that, except that now I’m not such an optimist. I think that after the Ant Farm exhibition, which was at the Berkeley Art Museum in 2004, I traveled to a few places. When I came back to make videos afterward, Elizabeth Kolbert’s book had just been published, the Sixth Extinction [2014], and I realized that we’re in the process of creating this extinction of our own species with climate change. So, I created several works in video about that, which had to do with the rising sea levels. One is called Miami Beach Elegy [2017], you know Miami Beach maybe isn’t going to exist by the end of this century. Another one is New York Underwater [2014], and that was preceded by a Hurricane Sandy, which flooded so much of Manhattan. So, I’m trying to shift my love of cars into loving trees.

KUPPER: You mentioned that you’re not so much of an optimist anymore, but do you think utopian thinking is still important?

LORD: You know, I’ll have to think about that question. I guess yeah, of course it is, but maybe utopian thinking is shifting now. I love this book, To Speak for the Trees [2021], by Diana Beresford-Kroeger. As a child, she was orphaned and went to live with her uncle in Ireland for the summer, and the people of that community decided to teach her Celtic knowledge. She had this intense learning experience about plants and other species, which led her to becoming a professor with a specialty in botany. So, that’s now utopian: understanding indigenous people, and indigenous ways, and the integration with other species we share the planet with. That’s so utopian now, because it’s so different from the mindset we’ve lived with throughout the 20th century. The Dolphin Embassy is one the most popular projects by Ant Farm. Again, it was simply a very symbolic idea, and we didn’t have the personnel, or the budget, or the power to find the scientists, and work with them, to make Dolphin Embassy a reality. It was a utopian idea, to focus on trying to communicate with another species.