Archizoom Associates, Florence, 1968. Members of the Archizoom group in front of the original headquarters in Via Ricorboli 5 in Florence. In order: Paolo Deganello, Lucia Bartolini, Gilnerto Corretti, [Natalino], Massimo Morozzi, Dario Bartolini and Andrea Branzi. Courtesy Studio Branzi

interview by Francesca Balena Arista

Archizoom Associati was founded in 1966 by Andrea Branzi, Gilberto Corretti, Paolo Deganello, and Massimo Morozzi. They would later be joined by designers Dario Bartolini and Lucia Bartolini. Deeply philosophical and metaphysical in their architectural investigations, Archizoom's major contribution was No-Stop City, an imaginary, always evolving, never-ending future city that utilized the power of technology for a non-hermetic, decentralized metropolis that met all its citizens' needs. In the following interview, architect and design scholar Francesca Balena Arista asks founder Andrea Branzi about his visions of these new urban environments.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: Within the general concept of utopia, you have maintained that your work was about a realistic utopia.

ANDREA BRANZI: Yes, I have always attached great importance to the intellectual history of transformations, being a philosophical, non-political process in history. That is, I have always considered the transformation of land as a philosophical concept, a slow transformation derived from theoretical thought. “Non-Stop City,” for example, is the presentation, the vision, of a territory that is altered over time, but lacks the unity of utopia.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: How do you define the project of “Non-Stop City?” What was its value at the time it was conceived and what is, even today, its importance and influence on the design world?

ANDREA BRANZI: This type of transformation from a real project to a philosophical adaptation regarding the absence of real history, where the city no longer has a traditional sense of history, but rather a slow continuous evolution, was derived from the work of other radical Florentine architects. It is the idea of a continuous, never-ending story that has no limit, a city without architecture where everything flows without ever stopping. This is the concept of “Non-Stop City.” The name anticipates the thought behind the project, yet it never ends. This is an integral condition of contemporary culture where there is never a final closure to the project.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: Let's take a step back to the birth of the name Archizoom. Is there anyone in particular among the group who thought of this name and what is its origin? What is the meaning?

ANDREA BRANZI: Before us, there was an English group called Archigram that was very important and very pop, but devoid of any political components—a very different position from ours at that time. Our political formations dates back to 1962, when we participated in student movements, especially the one led by Claudio Greppi, “Lega Studenti Architetti” [student architects league]. This experience was crucial to us, as it was through them that we obtained information about the emerging political philosophers. This allowed the birth of the Radical Movement in Florence. A large number of avant-garde groups were born: there were Superstudio, Ziggurat, Gruppo 9999, UFO, and more. It was a generation of Florentine architects who surprised the avant-garde magazines and publications. It was a pivotal moment. That was when the first Japanese groups arrived, trying to find out what was happening in Florence, Milan, and so on. Arata Isozaki came to Florence. There was a whole international movement around these avant-garde groups.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: The Florentine climate, when radical architecture was created and the first groups, Archizoom and Superstudio, were born, was deeply political, even if there were differences within the various groups. I am reminded of the Superarchitettura exhibition. You have always talked about this installation as a seminal moment. What is the meaning of Superarchitettura?

ANDREA BRANZI: Superarchitettura took place in Pistoia in 1966, in a sort of city center that actually sold fish, not art, but the first avant-garde works came out from there, that’s where we first discovered The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. It was a breeding ground for movements, something very different from the past generations. Florence has always been a historic city where the avant-garde did not exist. So, the idea of realizing a new modernity there allowed the birth of a phenomenon that was completely unexpected.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: And the flooding in Florence, in 1966? Did it have any repercussions on your view of the historic city?

ANDREA BRANZI: Certainly, the Florence flood was a striking phenomenon. The whole city was submerged in water and the monuments were devastated. However, it was like the end of an era, and the beginning of something new. It was like Pompeii; after its destruction a new civilization was born. The flood marked the beginning of a culturally different era.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: Let's talk about another vital moment that was recognized by the entire Italian design world, namely Emilio Ambasz's exhibition at MOMA, Italy the new domestic landscape (1972), which saw the presence of both avant-garde groups and what we can consider representatives of a more traditional thinking. What did it mean for you?

ANDREA BRANZI: It allowed us to bring together at least three avant-garde groups and some great professional designers, there were Ettore Sottsass, Gae Aulenti, Vico Magistretti, and many others. Italy presented itself through this exhibition as a land in which new things and new ideas were being born. After that exhibition, it had to be seen that the mass production industries, which were very powerful at the time, were going into crisis. Therefore, they began to experiment with craft movements, new languages and colors, new functions. The new Italian design movement was born, groups that were moving with very different logic, the Memphis Group for example. There was no longer the idea of mass production, but rather, the production of small series, of great expressiveness. It was a very important historical period that had a major influence throughout Europe and in Japan. It was a seemingly unpredictable, radical change that responded to new questions of industrial and craft production aimed at small experimental territories.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: Years later, in response to the exhibition, Emilio Ambasz said, "Design is not only the product of creative intelligence, but an exercise in critical imagination."

Archizoom Associati Mies chair, Poltronova Italy, 1969 chrome-plated steel, rubber, upholstery 30 h × 29 w × 51½ d in (76 × 74 × 131 cm)Courtesy Studio Branzi

ANDREA BRANZI: Yes absolutely, design is not exclusively related to the market. Behind these vanguards was a new philosophy. Just remember the early examples of "Domestic Animals,” the idea of using natural materials that change over time, like tree branches that somehow become a part of a perennially diverse series. It's a philosophy whereby objects are no longer reproduced serially but change over time. It's a totally different conceptual view that changed the course of design history.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: In Florence, in the radical design years, how did you envision the future? What came true, and what didn't? An important component of radical design was prediction and the will to propose something new for the future.

ANDREA BRANZI: All this happened following unforeseen conditions. When we came together, we were looking for our own name. I called the art critic Germano Celant and asked him what might be a suitable name for these Florentine movements. The next day, he called me and told me that the appropriate name was ‘radical,' which is different from the Italian ‘radicale.' It is a much broader concept, like ‘liberal’ to ‘liberale.’ We were not exactly aware of what was going on, at least the four of us—me, Paolo Deganello, Gilberto Corretti, and Massimo Morozzi. We constituted ourselves as a "leading" group and it came naturally. We managed to get four “30 e lode” [A’s] on the same day at the university. This surprised the whole town and spread to the others. We initiated a kind of autonomy within the university and schools in philosophical and creative thinking. This is the Radical legacy.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: What would you recommend to young people today who want to think and dream of a radical future?

ANDREA BRANZI: I see that young Italian designers these days are making overtly hostile objects. They adopt new, unpredictable languages, which are not easily marketable. They sure have a vitality that surprises me greatly, and I think can change the rules of Italian design. There is always a kind of leading position in Italian design...I don't really know what German designers, American designers, or French designers are doing, I'm very curious to see what will happen there, and in other countries, though.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: In this sense, you said that you have your own vision of utopia. What is the value of utopia for you, the value of critical thinking, and the value of going beyond what society offers us? When I think of the objects designed by Archizoom, I see them as "breaking" objects in the history of design. What did you want to convey to others?

ANDREA BRANZI: Not everything was clear in what we were doing. Things were happening that were "typical" and inherent to the concept of the new generation, and to work that follows non-traditional logic. The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, like other bands of the time, were not born in music schools, but in contexts where everything was happening in unplanned ways. There was no definite agenda or policy. The same goes for fashion: its future envisions something different from what the public expects. Fashion is now saturated with languages and quotations, so it has to turn to new and unpredictable figures.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: It seems like you are describing what you did after graduating from architecture school. It was clear that your Superarchitettura had different references than the traditional ones as you were inspired by pop art and those rock groups you mentioned.

ANDREA BRANZI: Certainly, and that still applies. Nothing is accomplished; everything is open to be revised in radical and profoundly different ways. I used the term ‘radical' in a book in which I describe the history of the movement, "Una generazione esagerata” [An exaggerated generation]. Our creativity was not controllable, and it is the same today. There is still so much empty space to invent new languages, colors, and forms.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: I am reminded of the first article in Domus in which Ettore Sottsass introduces the radical groups by describing the objects being made as "Trojan Horses" in our homes, as if they have the power to influence people's behavior.

ANDREA BRANZI: Yes, the idea was to make unpredictable objects, which can betray the classic expectation, surprising those who have them.

(Francesco shows Andrea some new drawings of naked women wearing what looks like thin strips of cloth)

You see, there is so much empty space to invent new images, and new thoughts. It is nothing gross. In fact, we could almost say it is sacred and ancient. Nudity is not something to be afraid of, but rather a place to imagine new elegance and new sacredness. Yesterday, I made these drawings … they surprised and fascinated me. They make me think of a new sacred fashion, not a vulgar one.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: Right now, you have an exhibition in New York, Contemporary DNA, at Friedman Benda Gallery. What is it about? What was the thinking behind this new exhibition?

ANDREA BRANZI: In this exhibition I show decorated bamboo canes, chairs, and maritime woods. The combination of these elements creates a completely unpredictable situation, which has nothing in common with serial production.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: It reminds me of one of your first works in the ‘80s, Animali Domestici.

ANDREA BRANZI: Animali Domestici was also done because Memphis and Studio Alchimia were at the end. They no longer had communication power. The idea of making objects, composed of tree trunks that joined together in ever changing ways, the idea of the diversified series, interested me a lot. I understood and interpreted what was previously just an idea. At first, I didn't really understand what I was doing. This was quite typical of my way of working, but also how other group members worked. We moved forward and then asked ourselves what we had done, and what it meant. I often create images that only then make sense. “Non-Stop City,” for example, was born by chance with my friends. We had no guiding idea. It was, rather, a philosophical thought about the continuous and unlimited extension of the urban territory.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: In the ‘70s you imagined the city as a flow of goods and information. It was a strongly anticipatory thought.

ANDREA BRANZI: Yes. When we started drawing, we didn't know what we were doing, yet all four of us knew we were doing something absolutely indispensable. We discussed, trying to interpret our drawings, and only then the idea of this city without architecture emerged, a city that never ends, without perimeter, which extends in thought, like a philosophical discovery. It is always very difficult to explain. This often happens to artists and painters though, doing things that you are not fully aware of.

FRANCESCA BALENA ARISTA: What importance do you attach to nature? You often include natural elements in your projects, following the idea of the diversified series, which seems to be for you an enrichment of the design world.

ANDREA BRANZI: Surely it is. I am not an environmentalist; I do not belong to the school of ecology. Of course, it must be noted that the industries continue to produce cars relentlessly. Perhaps we should do as in Japan and let them pass through the tunnels. There are many things to understand and I don't always understand what I do.

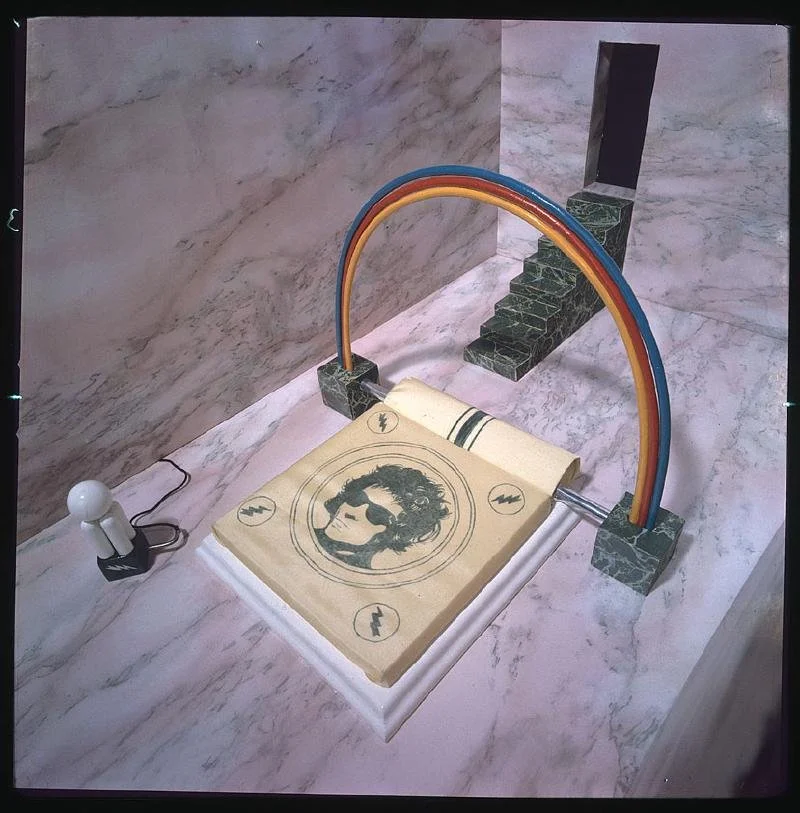

Archizoom Associati, The Four Beds,Institut d’art Contemporain Villeurbanne/Rhône Alpes in Lyon, 1967Courtesy Studio Branzi