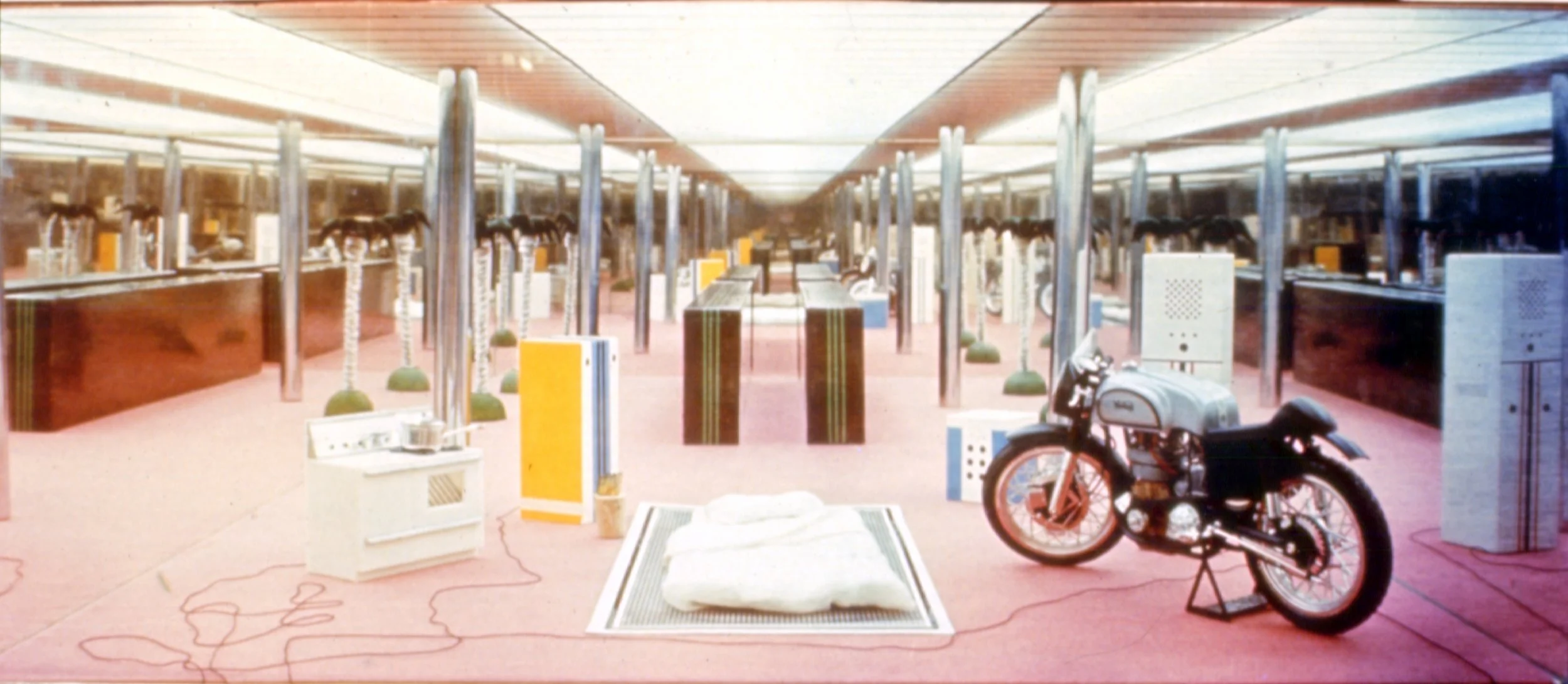

Archizoom Associati, No-Stop City, 1970. Internal Landscape. Courtesy Studio Branzi

interview by Oliver Kupper

In 1966, a flood washed over Florence, Italy. Over one hundred people died. Millions of Renaissance masterpieces, artifacts, rare books, and monuments were destroyed when the Arno overflowed and consumed the capital of Tuscany. But this was not the first time the city was overtaken by chaos and destruction. Twenty years earlier, the Nazis began a year-long occupation of the ancient Roman citadel. Allied and Axisforces shared a brutal exchange of fireand shelling that destroyed many of the buildings surrounding the famous Ponte Vecchio bridge, which was miraculously spared by Hitler himself (all the other bridges were destroyed). Out of the rubble and loam of this violent miasma came a group of radical young architects who formed avant-garde collectives and declared a philosophical war against architecture itself. Against the violence of the past. Against the barbarity of fascism. Against formality. Against history. Against rigidity and conservatism. These groups had names like Superstudio, Archizoom, Gruppo 9999, and UFO. They were more concerned with ideas than structures—building conceptual visions of new worlds rather than erecting edifices in the present. Although they only existed for a brief period, burning wild and bright and visionary, their output would leave a lasting architectural impression—later inspiring architects like Rem Koolhaas and the late Zaha Hadid. But while Florence might have been the epicenter of this new psychedelic activity, these ’superarchitettura’ groups spread across Italy—from Milan to Turin, to Naples, and Padua as highlighted in the landmark 1972 exhibitionItaly: The New Domestic Landscape at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curated by Emilio Ambasz. The new landscapes of these radical utopians explored speculative visions of domesticity that included themes of anti-design and protests against objects as status symbols—anchors of materiality that exemplified the hubris of a hyper-consumerist, post-war society.

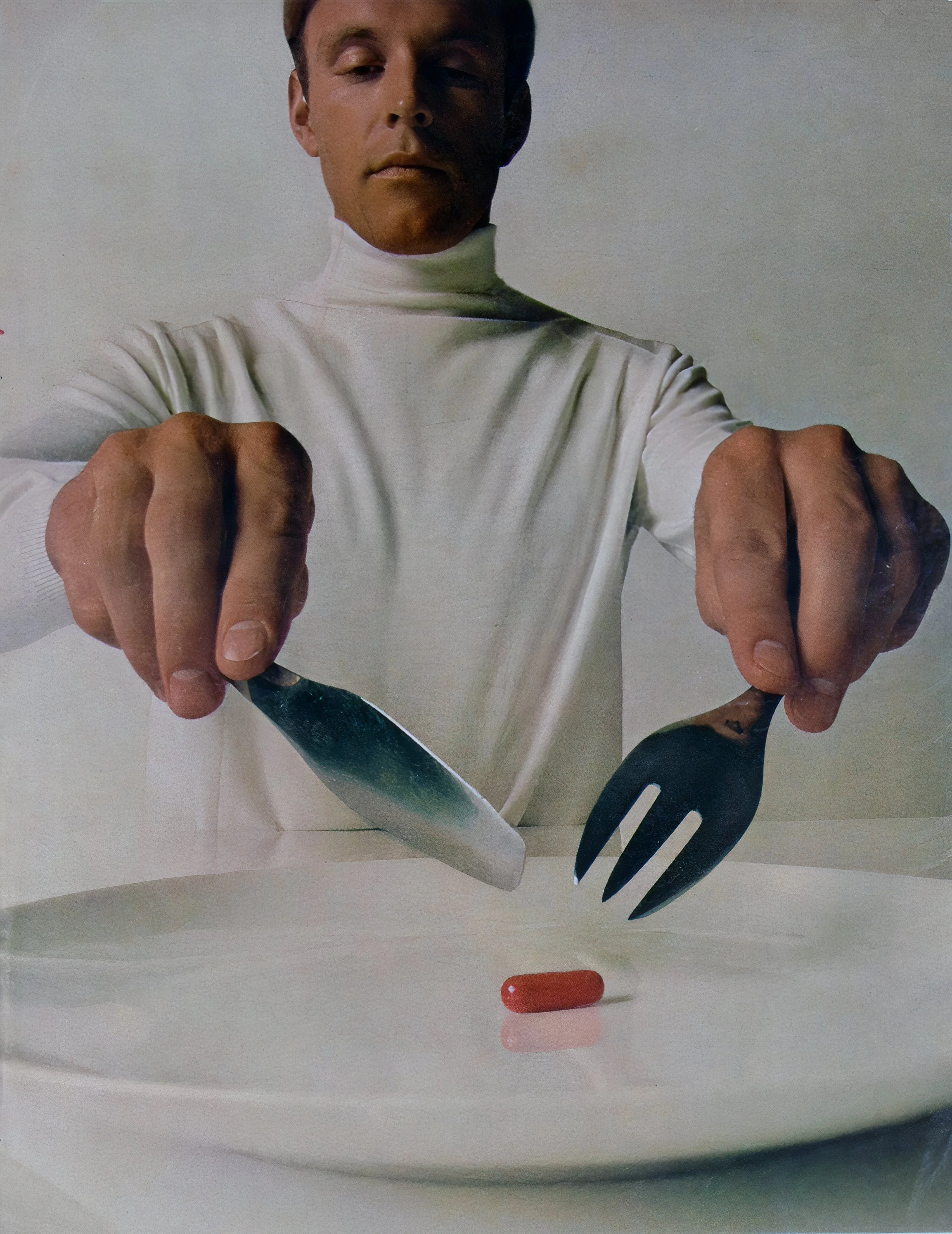

Superstudio, "Misura series" for Zanotta, 1970. plastic laminate with silkscreen print. Photographed in Panzano nel Chianti, Italy. Superstudio, Archive Cristiano Toraldo di Francia

Founded in 1966 in Florence, Italy by Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, and shortly thereafter joined by Roberto and Alessandro Magris, Gian Piero Frassinelli and Alessandro Poli, Superstudio’s psychedelic universe was an attack on modernism’s inherent failures. Utilizing photo collages, films and exhibitions, their vision was utopian at its core, but also examined the anti-utopia’s of urban planning pomposity with works like The Continuous Monument(1969), which was a singular gridded monolithic structure that spanned the globe. It cuts through meadows, cities, deserts and beyond. For Superstudio, the Cartesian grid, a system of x-, y-, and z-axes to control space, became their signature. Tables, benches and storage units are sold today with this pattern. In the following pages, the only surviving member of the group, Gian Piero Frassinelli discusses the group’s ambitions and his unique input, which was deeply steeped in his fascination and studies in anthropology. This translated to a vision of humanity returning to its nomadic roots, free from the slavery of labor and consumerist desires.

OLIVER KUPPER: Why did you gravitate towards architecture and were your architectural dreams before Superstudio always so radical and utopian?

GIAN PIERO FRASSINELLI: At first, I didn't have this utopic idea when I studied architecture. It took me a bit longer than usual to finish my architectural studies—about eight years. The word ‘radical’ wasn't used until after the creation of Superstudio, Archizoom, and all the utopian groups that were born during those years. The Superstudio group was formed during some of the toughest years for the university because classes were often interrupted. First, because of the flood in 1966. And later, in 1968, because of the student strikes. Those strikes were to fight the educational system in Italy and also to support peace all around the world. We were against the Vietnam War. Also, there was a huge gap between the ideas of the students and the teachers. So, we started to search for new ways of imagining what architecture could be.

KUPPER: You got your degree in 1968 and joined Superstudio the same year. How did you join forces with Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia who founded the group only two years before?

FRASSINELLI: I met Cristiano a few weeks before, on the street, casually. I hadn’t seen him since before the flood because I was preparing for my graduation project, and so I was spending a lot of time at home. Christiano told me about his studio that he founded with Adolfo and he told me to visit them when I graduated. After a few days, I finished my studies. When I arrived at their studio, they told me what their ideas of architecture were. At first, I didn't understand because my ideas were very different from the academic approach, but also from their point of view. But my architectural ambitions were very similar, so I decided to put my ideas aside and follow them.

KUPPER: You had an early interest in anthropology—why was that field of study important in the context of architecture?

FRASSINELLI: To be honest, my interest in anthropology came before my interest in architecture. I found myself in the architectural world because my dad used to sell building materials. His studio was packed with architectural magazines and books. My interest in anthropology started when I was a child. I got sick in a bunker during World War II, so I stopped attending elementary school for a few years. But I was lucky because I had an aunt who was a retired teacher. She taught me a lot to make up for the years that I had lost due to my illness. She was one of the first teachers to use the Montessori method. [Maria] Montessori was an Italian professor who changed the way of teaching. And she was a very religious person, so she did a lot of missions in Africa and other places. That’s how I learned about people who were very different from me, that had a very different culture and lifestyle than mine. I was around eight years old at this time. And from my dad’s architectural magazines, I got a passion for architecture. So, after high school, I enrolled in the University of Architecture in Florence. Over the years, I kept learning more and more about anthropology. My graduation project was a study about an anthropology museum.

KUPPER: Speaking of the war years. How did the ghosts of fascism in Italy, but also Europe at-large, in post-war Florence—a city steeped in the classicism of the Renaissance—inspire you as an architect and Superstudio?

FRASSINELLI: I was born in 1939, the exact day that Hitler invaded Poland. The next year, the bombing started in Italy. The bombing first started in La Spezia, which was the city where I used to live. Every night, we heard the sirens. We had to spend most of our life in the bunkers there. We actually moved from La Spezia because our house was destroyed in the bombing. So, we moved east and arrived in an area close to the Apennine Mountains, which was the location for a lot of Nazi killings. You’ve probably heard about Marzabato, which was the location of one of the biggest Nazi massacres. We were lucky to survive. It was a miracle. So, when we arrived in Florence, it was almost the end of World War II, but a big part of the city was destroyed, and there were land mines everywhere. Seeing the destroyed architecture was really influential for me and for my architectural point of view.

KUPPER: In connection to these totalitarian regimes and architecture, most people associate the Cartesian grid with rigid structures, conservatism, staying within the lines, but Superstudio’s imagination existed way outside these lines, what did the grid represent and why was it so important?

FRASSINELLI: The grid was actually developed casually. I was working with Superstudio for a year, and I was more like a draftsman than a researcher. At one point, Adolfo and Cristiano had the idea of building the Continuous Monument. They needed someone very good at drawing perspective. I was actually hired for drawing perspective and also photo collages. Also, during my studies in high school and university, to draw perspective, I always used the Leon Battista Alberti method. Leon Battista Alberti was one of the most important architects and artists in Florence. And that method consists of dividing each volume into squares using a grid. This is also how the grid made its way into the photo collages.

KUPPER: And the grid sort of took over everything—even tables and chairs. It became a main symbol of what Superstudio did.

FRASSINELLI: With architecture, we later moved forward from the grid. For the design aspect, the grid became iconic. A lot of people requested it. And Zanotta still produces Superstudio furniture with the grid. As for the drawing, the grid was just a way to emphasize the bi-dimensional volume.

KUPPER: This Cartesian order of the natural world through dominating monuments of architecture, like The Continuous Monument, which could soon be a terrifying reality in the Saudi desert, was described by Adolfo Natalini as an “anti-utopia.” Where did Superstudio’s intuition about the terrors of architecture’s future anti-utopias come from?

FRASSINELLI: The Continuous Monument was first an idea that Adolfo and Cristiano had to connect architecture from all around the world—to connect all the architectural methods. And the grid helped to put this in order and to be more rigid. But the problem for me, because of my anthropology studies, was that it led me to think that the interior of the Continuous Monument would be terrible to live in. So, the Continuous Monument was born as a utopia but died after my talks with Adolfo and Christiano, and became an anti-utopia.

KUPPER: One of your major contributions is “The Twelve Cautionary Tales [12 Ideal Cities],” which was extremely anti-utopian. Can you talk about this?

FRASSINELLI: “The Twelve Cautionary Tales” happened during a period when Adolfo was teaching at a university in the United States, so it was just me and Christiano here in Florence, and we didn't have that much work to do. It was a better way for me to explain to Adolf and Cristiano what life would actually be like inside The Continuous Monument. I took the ideas of the other eleven cities by focusing on crowded urban places all around the world that somehow don't work. Each city, each cautionary tale, is a different thing that doesn't work in those cities. I chose the number twelve because twelve is a very important number for Western culture and literature.

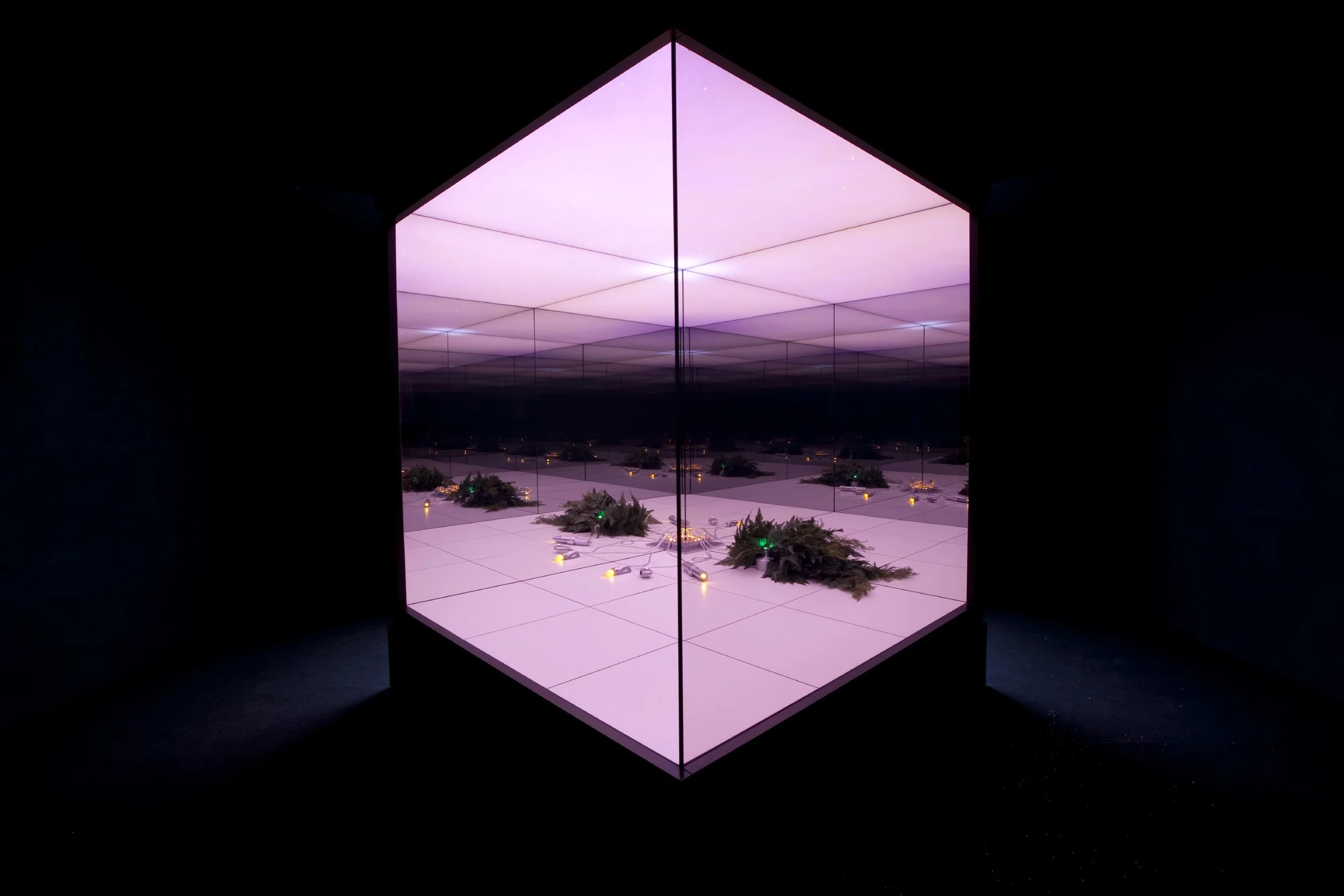

Supersuperficie for 'The New Italian Land-scape' exhibition, MoMA, New York, 1972. Migrazione, screen printed plastic laminate for Abet Print, 1969. Superstudio, Archive Cristiano Toraldo di Francia

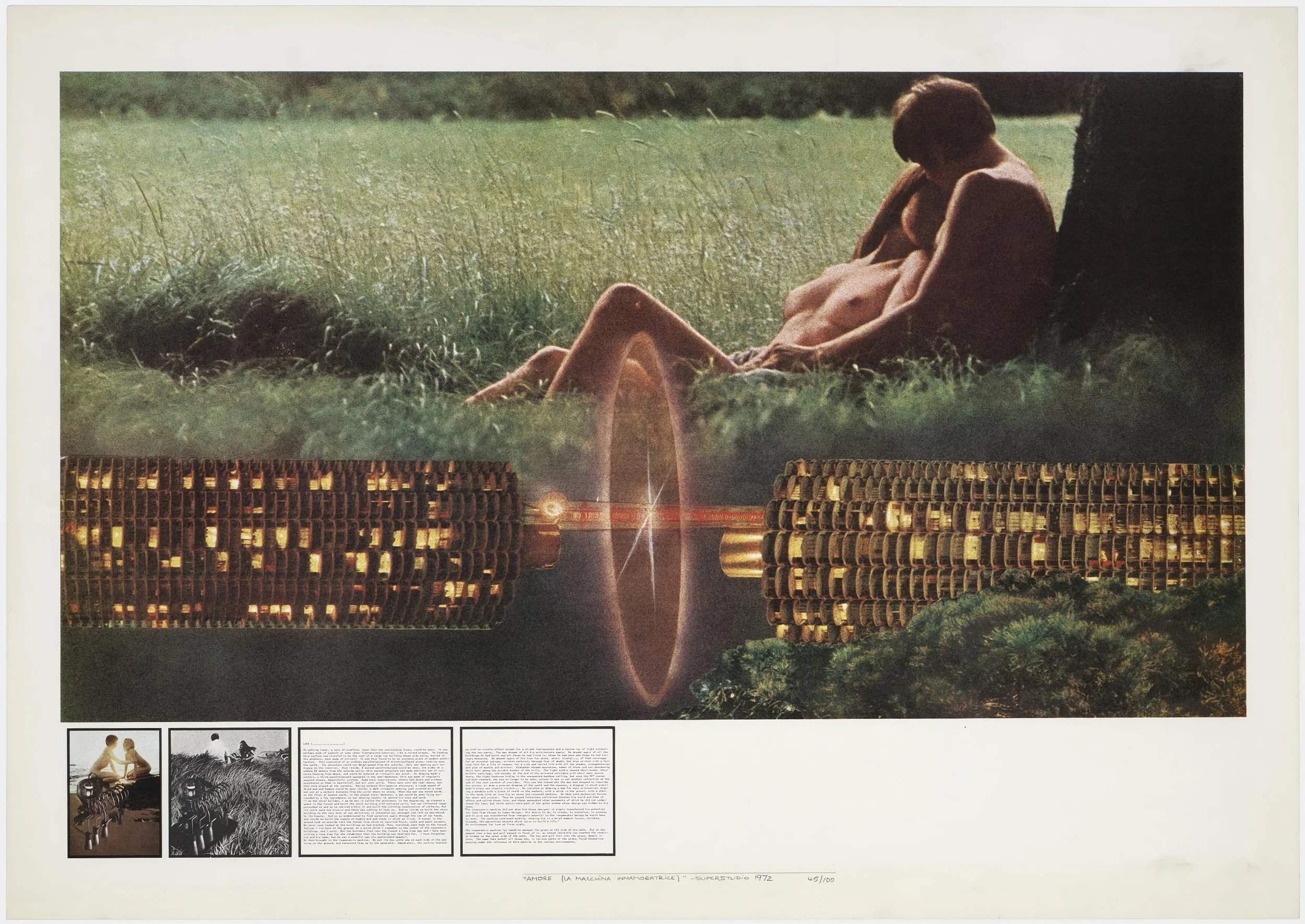

Amore. La macchina innamoratrice Collages et crayon blanc sur tirage, 60 × 80 cm © Superstudio, Archive Cristiano Toraldo di Francia

KUPPER: Film was a powerful medium for Superstudio. I'm thinking about the short thesis film made for the exhibition at MoMA, Supersurface [1972]. Can you talk about that film and the power of moving images?

FRASSINELLI: To be honest, me and Cristiano started to make a movie during the university years with a few friends who didn't study architecture. It was about the Christian Gospels, but we had to interrupt it because we discovered that Italian director and writer, Pier Paolo Pasolini was actually preparing a movie that was about that. So, we decided not to compete with him (laughs). So then, there was another movie, which was less known. It was called Interplanetary Architecture [1972], and it was before Fundamental Acts [1972].

KUPPER: Where did the love of film come from?

FRASSINELLI: At the time, there was no TV at home. So, the cinema was very important for all of us because it influenced our life a lot, and gave us a lot of poetic ideas. We watched the movies of Fellini, Pasolini, and Antonioni.

KUPPER: You mentioned Fundamental Acts, which explored the five fundamental acts of a person's life. It was a very poetic project. Can you talk about this series and why architecture doesn't consider the human body or experience?

FRASSINELLI: My awareness of architecture began when I was very young, basically when I was born. I remember our first apartment in Florence after World War II. It was my first architectural experience and I was around seven years old. My family decided to visit another family that lived in the same building. When we entered this apartment, I actually saw my own apartment, but with different furniture and organized in a different way. This was a really visceral experience that was actually painful. This memory popped when I started my architectural studies. From that experience, I decided not to design a single apartment that was the same as another. Going back to my anthropological interests—in Western society, we have this concept of apartments and buildings that are very homogeneous, but in other societies and cultures, all the buildings are different from each other.

KUPPER: So, it's important to consider a person's life and bring humanity back into architecture.

FRASSINELLI: It's probably because of the humanity in architecture that I was always inspired and interested in anthropology. A lot of architects actually ask me what anthropology has in common with architecture and why it is necessary to architecture. And my answer is always: all the architecture is lived in by humans.

KUPPER: Nomadism and nomadic society is an important part of Superstudio’s architecture ambitions and it is also related to anthropology. Humans used to be nomads and there are still a few nomadic societies out there.

FRASSINELLI: Nomadism is the other face of architecture because it's actually life without architecture. In Western society, we have this obsession with work. In nomadic society, they would work just five or six hours a day to find food, and the rest of the time is just to enjoy their own life, which is talking to each other, learning different things or spending free time with each other.

KUPPER: On the other side of it, now with global warming and war, we have people who are forced to enter a nomadic lifestyle. Climate refugees they are called. How do you think architecture could rectify that, or build a better future for people forced to become nomads?

FRASSINELLI: There are a few people trying to do that, but it's very difficult right now because the architectural world operates on a purely economic basis. There has always been a war between those who are richer and those who are poorer. Right now, there are more than a billion people not living properly all around the world, and the hope that I have is that we will try to help the people who are forced to be nomadic. This is separate to nomadic societies, because these societies can actually offer us a closer look at how humans can live in better harmony with nature.

KUPPER: What is your advice to young architects today with utopian visions of the future?

FRASSINELLI: Young architects are the first to be in a prison of their own culture. My advice is to really change the structure of the society where you live, because otherwise, there's no chance to survive.

Supersuperficie for 'The New Italian Land-scape' exhibition, MoMA, New York, 1972. Migrazione, screen printed plastic laminate for Abet Print, 1969. Superstudio, Archive Cristiano Toraldo di Francia

Amore. La macchina innamoratrice Collages et crayon blanc sur tirage, 60 × 80 cm © Superstudio, Archive Cristiano Toraldo di Francia