Autre editor-in-chief Oliver Kupper spoke with titan of avant-garde theater Robert Wilson in the lead-up to his installation at Salone del Mobile.Milano, opening April 6.

Robert Wilson. Mother Museo della Pietà Rondanini Castello Sforzesco Salone del Mobile.Milano 2025 © Lucie Jansch

interview by Oliver Kupper

Michelangelo was working on the Pietà Rondanini the week that he died. Perhaps eclipsed by his naturalist and expressive Pietà housed at Saint Peter’s Basilica, which is considered one of the great masterworks of the Renaissance, the Pietà Rondanini may seem crude in comparison. Many scholars consider the work to be unfinished. There is an openness to it—in the roughness of the features, in the ambiguity of the figure cradling Christ, and in the specifically rendered but detached arm that stands beside the sculpture’s primary characters like a sentinel.

The statue, which confounded art critics for many years, was championed by the great modernist sculptor Henry Moore. In his collected writings and letters, Moore noted of the statue, “This is the kind of quality you get in the work of old men who are really great. They can simplify; they can leave out.” At 88 years old when he sculpted the Pietà Rondanini, Michelangelo’s sculpture was less of a sermon and more of a prayer: some things need no explanation.

At 83 years old, Robert Wilson is something of an old master himself, although he has approached his entire career with the confidence of an artist who knows not to carve away more than is needed. Beginning with light and formalist performance schematics, Wilson has staged some of the most renowned avant-garde theater works of the 20th century. From collaborating with minimalist composer Philip Glass on 1976’s marathon opera Einstein on the Beach to directing theatrical masterpieces from Wagner, Brecht, and Beckett, his formalist approach provides structures for audiences to encounter extended stretches of space, time, and silence.

Born in Waco, Texas, Wilson moved to Brooklyn in 1963 to study architecture at Pratt. A day job working with comatose patients at the Goldwater Memorial Hospital on Roosevelt Island sparked an early interest in signs and signals that transcend language, which suffuse all his performances. Wilson has collaborated on theatrical works with Rufus Wainwright, Laurie Anderson, Tom Waits, Lou Reed, Anna Calvi, and William Burroughs.

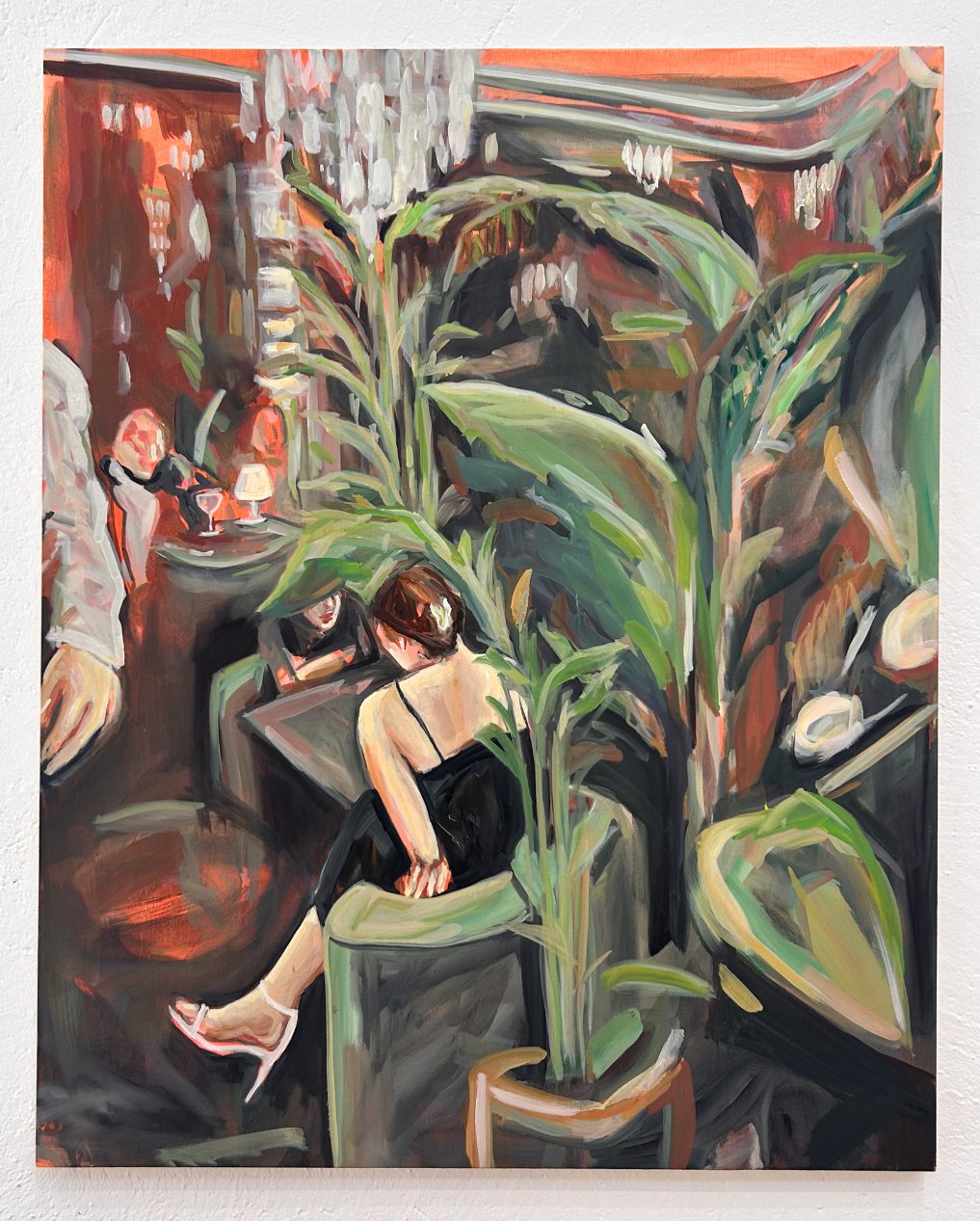

On April 6, Wilson will kick off the Salone del Mobile.Milano with a new installation at the Castello Sforzesco titled Mother, centered around Michelangelo’s final and unfinished Pietà. Featuring music based on a medieval prayer arranged by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, Mother will explore the enduring universality of the image and emotion of Michaelangelo’s final work. In the run-up to Salone, Autre editor-in-chief Oliver Kupper spoke with Wilson about his early years in New York, his creative process, and the limitations of interpretation.

OLIVER KUPPER: I wanted to start in Waco. What was your access to the avant-garde – or was there even access?

ROBERT WILSON: I grew up in Waco, Texas. It was a right-wing community, very Southern Baptist. Waco was segregated. It was difficult to walk down the street with a Black man. Not much culture.

I was fortunate enough to be introduced to a man named Paul Baker who at that time was head of the theater department at Baylor University. They were doing experimental work. It was quite amazing the way he had an integrated program with the arts whether it was painting, sculpture, or performance. He thought about it in a very open way. That was a window to another world when I was growing up. At a certain point he left Waco and went to San Antonio to Trinity University, and it was a great loss for this conservative community.

One of the positive things is that I connected with the Black community. That was a real beginning of another way of thinking. What was amazing about the Black community is their positive attitude. Here’s a race of people that have been beaten, enslaved, shamed, not allowed to read a book except the Bible. They wrote music in the spirituals that were all about hope. Martin Luther King Jr. and the protests, the peaceful marches were an awakening for me and had a profound influence on my work and life.

KUPPER: Were you ever a part of those marches?

WILSON: A little bit, but mostly it was an awakening.

KUPPER: What called to you about New York?

WILSON: New York at the time was a prime epicenter of experimental theater. New York to me was being in a community that had so many different viewpoints, different races of people, getting on a subway and seeing people from all over the world. It wasn’t so much what I was studying at school but the experience of being in a large city with so many people of very different beliefs and cultural backgrounds than mine. That was very exciting and still is.

In terms of the cultural scene, I went to Broadway plays and didn’t particularly like them. I went to the opera, and I strongly disliked that. I became interested in the work of [ballet choreographer] George Balanchine. I liked it very much, and I still go back. I especially like the abstract ballets of Balanchine. There was so much space and time to think that I didn’t find in Broadway plays. They were so visually appalling, and the opera was worse.

I was looking at classical sculpture and classical architecture. I entered into the artistic world by going to the New York City Ballet and later seeing Merce Cunningham and John Cage and how they structure time and space. The abstraction of the work and the freedom of the mind… to experience their work is very important. For Cunningham and Cafe, the visual was not an illustration. It wasn’t a decoration to a text. It was something independent and had its own integrity, conceived as a standalone. As someone who saw the world more visually, this was an awakening.

KUPPER: Can you talk a little bit about your work with polio patients?

WILSON: I worked at Goldwater Memorial Hospital, which was isolated in the middle of the East River. I worked there for a few years with people in iron lungs. Only their head sticking out of the tank. Most of them were catatonic.

I’d meet these people – someone who was 33 years old. He was married and had two kids and was a young lawyer who was in a car accident. They were told that he was paralyzed from the neck down and that it would cost $175,000 a year at that time to keep him alive on an artificial respirator. He was put in the welfare hospital. The first year, his wife came to visit him every day. The next year, maybe three or four times a week. After five years, she had her own life and maybe she came once a week. Patients like this became very isolated, in most cases, became catatonic.

I was hired as a physical therapist to encourage patients to speak. I developed certain techniques that would bring people together in a solarium, maybe eight or 10 people, and see what I could do to have them communicate with one another and with myself.

After a few years, when I decided to move on and do other things, I wasn’t so sure that it was necessary that they speak. There was a man that I’d spent a little over two years sitting beside, speaking with him, and he never spoke. I told him that I was leaving him, that I enjoyed getting to know him. And he said, “My problem of not speaking is not really a problem for me. It’s more of a problem for others. My condition, the way I am, I’ve learned to live with it. It’s really okay. It’s more of a problem for people from the outside world.”

I made a work a couple of years ago in Hamburg called “A Hundred Seconds to Midnight.” It was very much influenced by my time working at Goldwater Memorial Hospital with people in iron lungs and that world, that mental space of living in that world.

My first major work in the theater was seven hours long and silent. It was shown in Paris. And much to my surprise, it was a big success. We played for five and a half months to 2,000 people every night. Etel Adnan, the poet, philosopher, artist, writer came to see it and said, “I’ve seen the play three times, and I like it very much.” And I asked, “Why did you like it?” And she said, “Because it gives me time to think and time to dream.” I think that stems from those years that I spent working in Goldwater Memorial Hospital.

I had also adopted a deaf mute boy who’d never been to school. He thought in terms of visual signs and signals, and that silence really transcends language in a way. It’s the universal language of movement. I think that’s one reason my work has been accessible. I’ve worked in the Far East and the Middle East and throughout Europe, North America, Latin America, all over. I think it’s because I stage work, first, visually.

KUPPER: I read a piece by Robyn Brentano about your work and your approach to the performers that you work with. You’ve worked with a lot of performers from all walks of life, and you’ve also worked with a lot of collaborators like Philip Glass. How do you approach collaborators versus performers?

WILSON: Usually I start with an abstract structure. It’s coded in math. Einstein on the Beach was four acts and three themes – A, B, and C – and they recurred three times. I could diagram it, see it.

I make a map where I can readily see the whole picture very quickly. I once made a play that was seven days long, but I diagramed it quickly in just a couple of minutes.

KUPPER: Einstein on the Beach was your most famous work. Why do you think that piece was so revolutionary?

WILSON: It was classical. People said it’s avant-garde. But actually, if you look at it abstractly, it was a theme and a variation. That’s nothing new actually. That’s a classical structure. The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin: seven acts, one and seven related, two and six related, three and five related, and four in the center, spiraled in and spiraled out. That’s King Lear. The first half is in a manmade environment. The center line Lear says, “I shall go mad,” and the second half is in nature. The turning point was right in the center.

I think that when we’re all born, in our unconscious minds are the classics, and we have to rediscover them. Socrates said, “The baby is born knowing everything. It is the uncovering of the knowledge that is the learning process.” And I think that is always rediscovering the classics.

KUPPER: In terms of visual art and theater, which overlap and interplay in your work, how do you approach a visual artwork versus a work for the stage? How do you balance visual and narrative elements?

WILSON: I start with light. Light’s what creates the space. Very often people working in the theater, they write a play, they write an opera. They cast it. They rehearse it. And two weeks before they open, they light it.

Louis Kahn spoke when I first went to school to study architecture here in New York. He said, “Students, start with light.” It had a profound influence on me.”

KUPPER: Speaking of light, your upcoming work at Salone del Mobile Milano, Mother. Can you talk about that work?

WILSON: It’s a construction in time and space. You do one thing and then the next thing is something else, and then you do something else. I don’t think of it in terms of a narrative. In terms of time and space, [I think about if] this is quicker than that or slower. This is rubber. This is smoother. This is more interior. This is more exterior.

KUPPER: How is music going to be incorporated into this piece?

WILSON: I haven’t done it yet, so I’m not sure. Music is freedom. Freedom of the mind. When you listen to the radio, you’re free to imagine pictures. So what does the room look like? What does the person that you’re listening to look like? The interior visual screen is boundless. You’re watching a silent movie. You’re free to imagine sound.

The work for me is a bit like if you take a silent movie and you take a radio drama and you put them together. You have a different kind of space. Etel Adnan said the work gave her time to think. So often we don’t. If we go to an exhibition or we go to a performance, if we go to the opera, if we go to a play, we don’t have time to think. You’ve got so much information coming at you that you’re trying to process. How do you create a situation where you do have time and freedom to think.

How do I look at the unfinished Pieta of Michelangelo? It’s full of meaning. My work has never once been interpreted. In working 50 years, I have never once told an actor what to think. I give very formal directions and structuring of space, but interpretation… I don’t get involved with that. I come from a more… zen world.

Our education in the West is primarily based on Greek philosophy. I do something because of a reason. I don’t need a reason to do something. Later you can, if you want, find causes or reasons for why you’re doing what you’re doing, but I don’t start there. Most people working in the theater start with a reason and then they make an effect. I start with the effect.

Robert Wilson. Mother is on view April 8 - May 18 @ Museo della Pietà Rondanini – Castello Sforzesco

Free entry on 6th April to mark Milano Art Week

Project curated by Franco Laera. Production Change Performing Arts

A Salone del Mobile.Milano event in collaboration with the Municipality of Milan | Culture Admittance by reservation only.