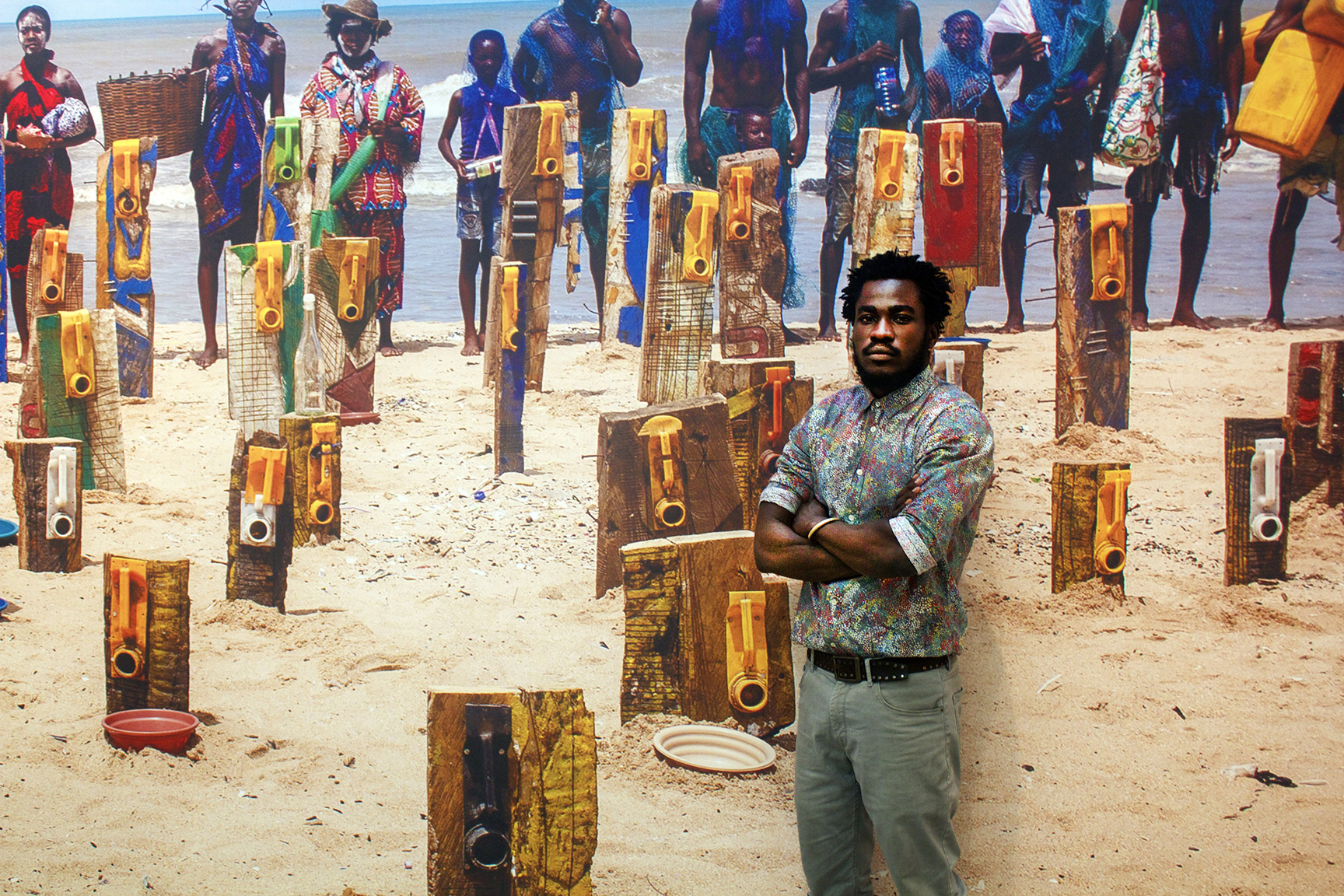

interview by Carlos Kong

portraits by Burak Isseven

styling by Hakan Solak (all looks GmbH)

Theodoulos Polyviou is an artist whose practice explores the multilayered spaces where queerness, spirituality, and cultural heritage overlap across physical and digital worlds. Often utilizing virtual reality (VR) technology, Theo’s work also features architectural and sculptural elements, text, and sound, resulting in installations that are at once intellectually deep and sensuous to experience. He has participated in numerous exhibitions and residencies throughout Europe, and has a forthcoming project in Lecce, Italy, later this year. I met Theo on the occasion of his recent exhibition Transmundane Economies at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin, where he has pursued a long-term artist residency. As an art critic, I’m usually hesitant and skeptical regarding the experience of art in virtual reality. But I found how Theo uses VR in Transmundane Economies to construct a “ritual space” that conjoins queerness, religion, and Cypriot cultural heritage to be profound and compelling. So I’ve met with him again to find out more.

CARLOS KONG: How would you describe yourself? Who is the real Theo?!

THEODOULOS POLYVIOU: I am inherently lost, or maybe by choice—I don’t know. But for me, being lost allows me to dig into subversive and irrational ways of navigating life, and this informs my practice. It gives me the freedom to partake in rituals of collective disorientation and becoming.

KONG: We met at your recent exhibition Transmundane Economies at Künstlerhaus, Bethanien in Berlin, where you’ve been an artist-in-residence since December 2020. Tell us a bit about your show.

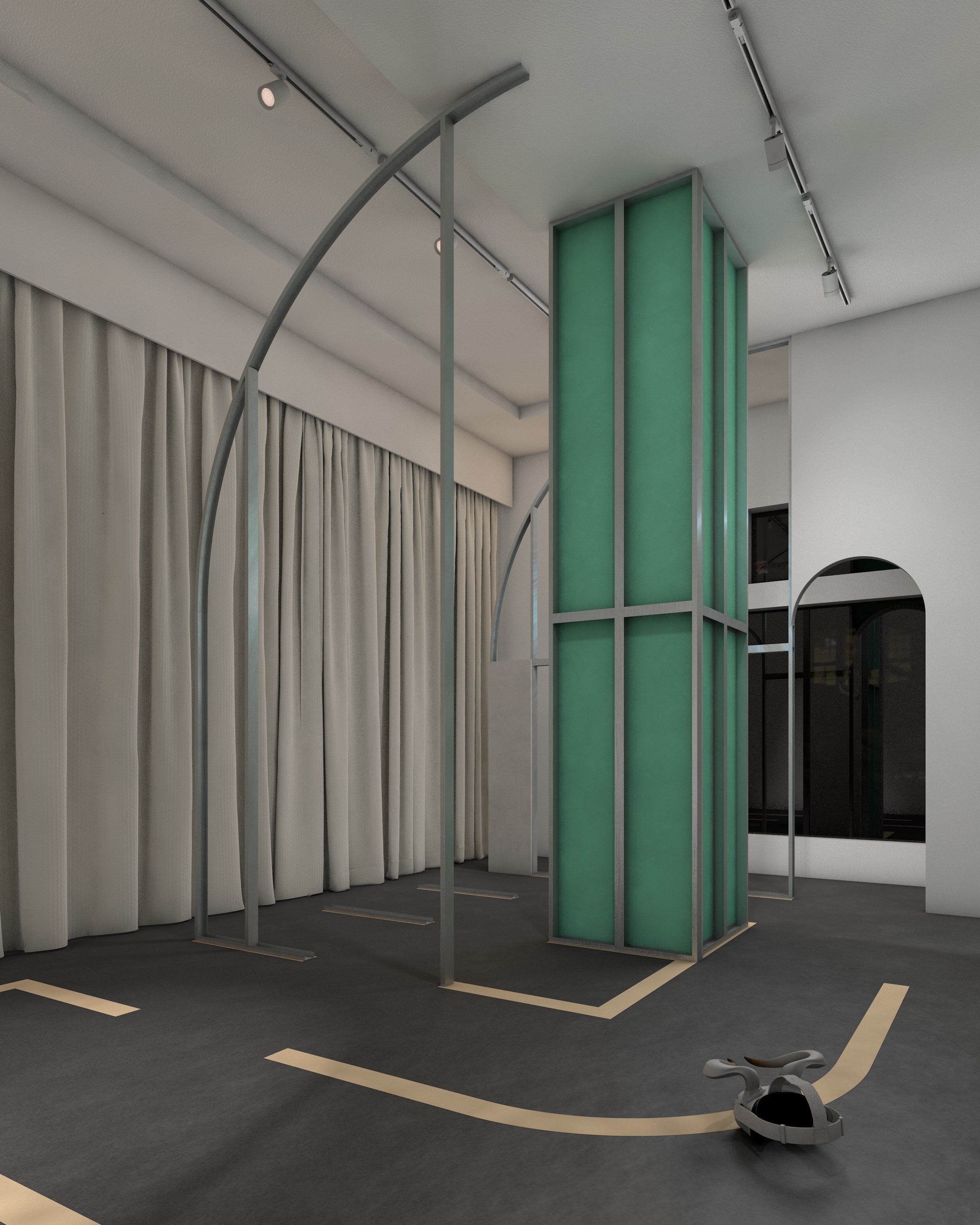

POLYVIOU: My latest exhibition is one of many chapters that constitute Transmundane Economies, an ongoing project that deals with Cypriot cultural heritage in relation to virtual reality. It explores the complexity of immersive media—its experiential, epistemic, social, and economic dimensions—in relation to cultural, historical, and educational practices. I investigate how media-augmented renderings of history encounter the physical premises of museums and institutions. The figurations between cultural heritage and virtual reality generate information through their clashes and compatibilities.

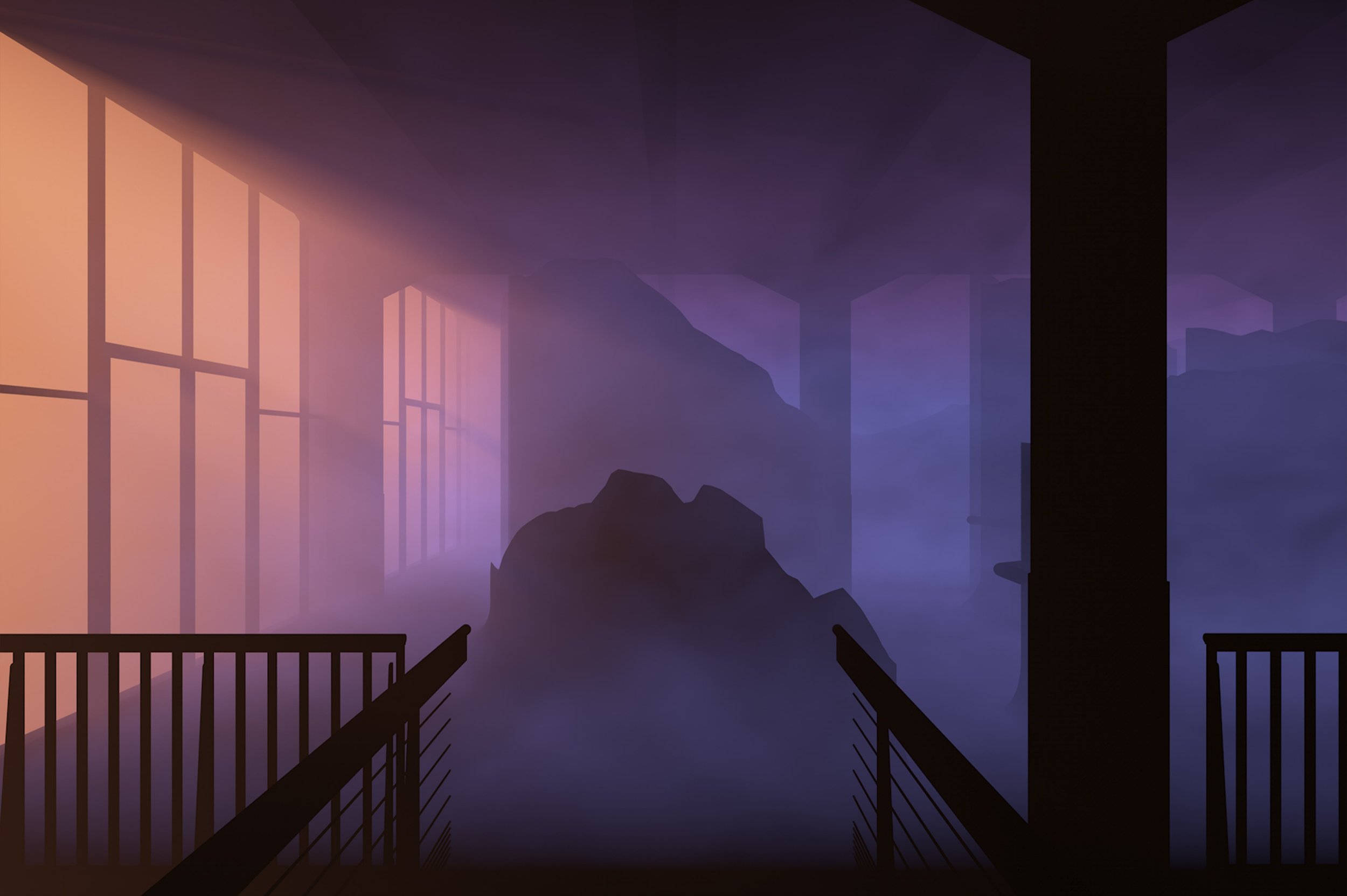

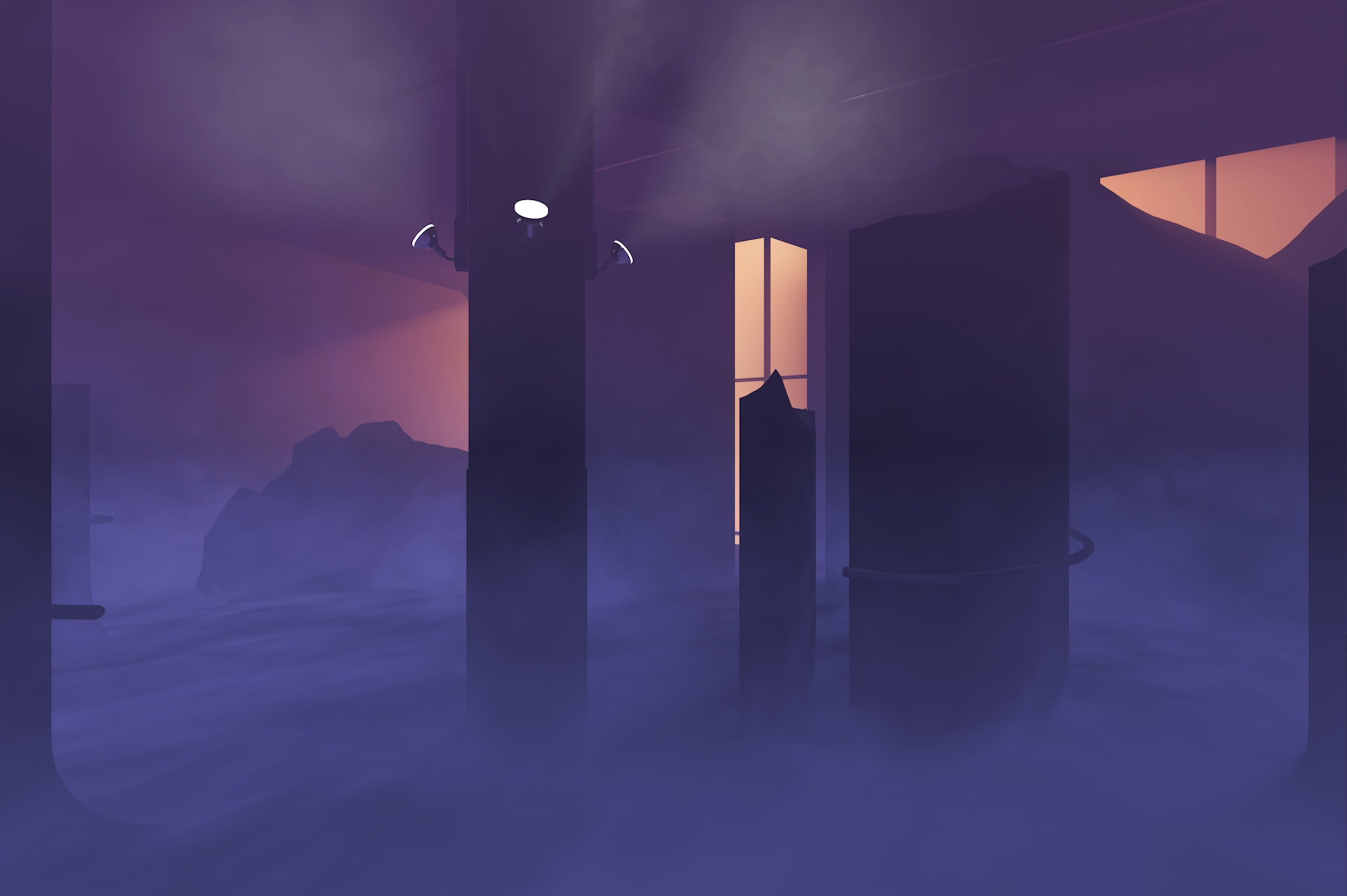

KONG: In Transmundane Economies, you use virtual reality (VR) to digitally reconstruct Bellapais Abbey, the ruin of a 13th-century monastery in present-day Northern Cyprus. What drew you to this site?

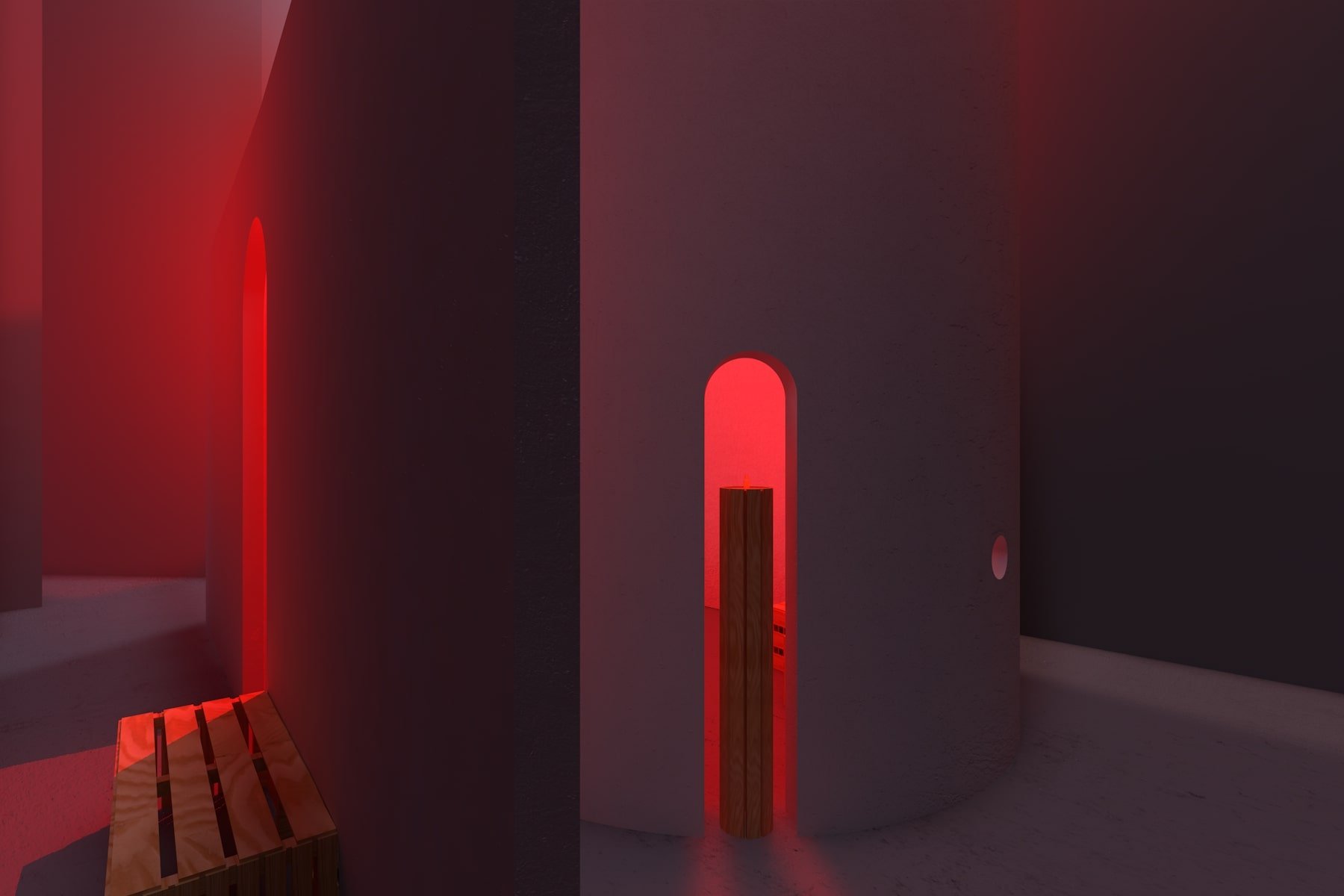

POLYVIOU: Bellapais Abbey is a relic of many lives. Following the different colonial periods of Cyprus, the monastery went through various architectural and cultural changes, which continually altered its organization and operation. Transmundane Economies takes Bellapais Abbey as a site of inquiry. In collaboration with the architect Dakis Panayiotou, we’ve recreated part of the monastery using virtual reality and transposed it within the premises of Künstlerhaus Bethanien, extending its long-lasting and shape-shifting history. By immersing physical bodies in our virtually-invented trajectories, the project proposes alternative ways of inhabiting the monastery’s ruins. The project’s virtual orientation system disrupts the traces of previous ways of navigating the site left behind by former colonial interventions.

KONG: In both your latest exhibition and throughout your practice, you’ve recreated specific architectures in virtual reality. How have you come to use VR, and what are its advantages?

POLYVIOU: VR allows me to create spaces of ephemeral nature. Using VR, I construct temporary spaces, free from usual structures. I think of them as ludic social spaces or as secular chapels. They are nonetheless reminiscent of actual chapels I’ve seen in Cyprus, which connect segregated communities and towns of deregulated planning on the island. The psychological dimensions of the spaces I create become ‘materialized’ through VR, and the immersive experiences of VR are a participatory process. In doing so, VR allows me to extrapolate how the practices and ceremonial expressions born in my work could potentially acquire social meaning in the future.

KONG: When I experienced your exhibition Transmundane Economies, I couldn’t help but think of the act of queer cruising—the back-and-forth energy of potential erotic encounters—as I circled through the dim corners of Bellapais Abbey in virtual reality. Some would view queer spaces as the opposite of religious spaces, but you’ve mentioned to me that both are structured by rituals. What interests you most about “ritual spaces”? How are queerness, religion, and cultural heritage connected in the context of Cyprus and within your work?

POLYVIOU: Indeed, my work addresses spaces of ritual, but it departs from museological approaches to religion that are bound to material objects. Instead, I use virtual reality to address the limits of storing religious objects within museums, opening new potentials for spirituality to be designed and experienced in the digital age. I’m most interested in ritualized performances as a social strategy; the construction of memory and space through both queer rituals like cruising, as well as religious rituals; and the emergence of new social identities and queer spaces through digital collectivity. The new identities produced in ritual spaces provide access to history, ancestry, and spirituality in ways that challenge the distribution of material wealth and the status of borders and territories. With regards to queerness and religion, institutionalized religion has had a strong influence on the political affairs of Cyprus by instrumentalizing a sense of national collectivity. The queer community on the whole island is not only subjected to marginalization based on their sexuality but also due to number of processes of identity formation and discrimination. My work is an offer to discuss mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion, and to consider how any place can transcend its own physicality to escape its embodied, ideological power.

KONG: Many of your works are made through collaboration. You produced Transmundane Economies with the architect Dakis Panayiotou, who you have been collaborating with since 2018 and with whom you contributed work to the Cyprus Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennial in 2021 as part of the group exhibition anachoresis: upon inhabiting distance. How do you work with your collaborators?

POLYVIOU: My work is of a collaborative nature indeed. Amalgamating different voices in my practice removes the focus from individual creativity and provides an opportunity to devise a ‘hybridic’ mode of production. I employ processes of dialogue and collaboration across different disciplines, including spatial design, architecture, sound, and even scent-making. My long-lasting friendship with Dakis Panayiotou has stretched out a collaboration that has traversed projects and residencies over the past four years. I believe the two of us find harmony in contradiction. Our differences complement each other and our collaborations become mechanisms to explore the potential dynamics of collective failure. I’m also interested in engaging with open forms of audience participation. This too is a form of collaboration, crucial to the completion of the work. The process of consciously involving visitors transmutes the exhibition space into a place of ritual, where they can connect with the transcendental world in a process of self-identification as spiritual beings.

KONG: You will soon be an artist-in-residence at Kora Contemporary Arts Center in Lecce, Italy. What will you be working on there? What’s next for you?

POLYVIOU: I was invited for an artist residency at Kora Contemporary Arts Center in Lecce, Italy, where I’ll be working site-specifically during April and May in Il Palazzo Baronale de Gualtieris, a 13th - century castle in the town Castrignano de’ Greci. The work will be then presented as part of a group show running from July 2022 through June 2023. From May 10-14, 2022, Akademie Schloss Solitude will organize the festival “Fragile Solidarity/Fragile Connections,” where I’ll give a talk in conversation with writer Jazmina Figueora. I’ll also be premiering a video on Kunst-tv, curated by Daniela Arriado and Vanina Saracino later this spring. More to come after September, but I can’t disclose the specifics :)

longsleeve: Theo’s own, trousers & boots: GmbH