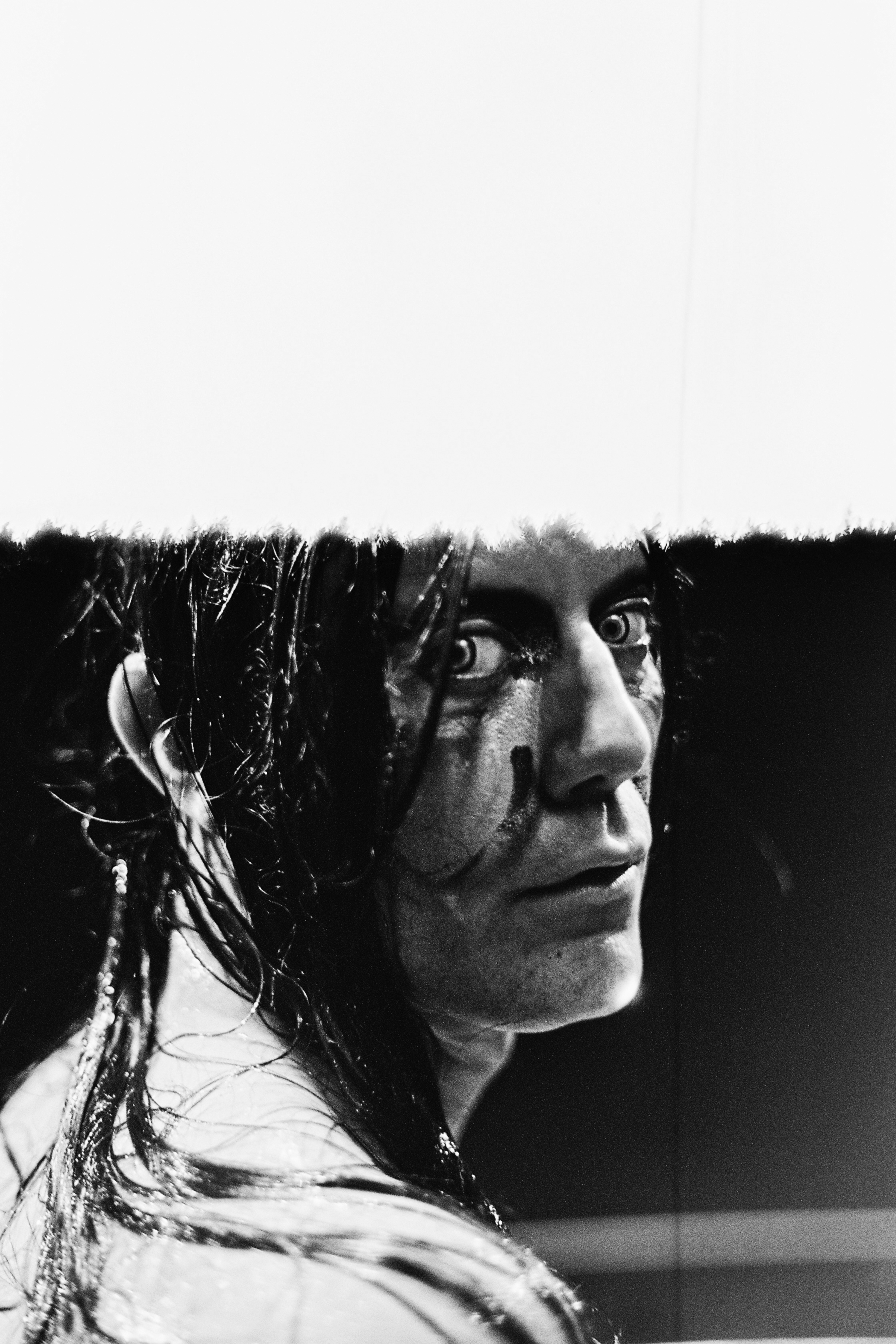

interview by Summer Bowie

creative direction & photography by Dana Boulos

styled by Janet Gomez (all looks No Sesso)

makeup by Yasmin Istanbouli

photography assisted by Bono Melendrez

produced by BRAINFREEZE Productions

special thanks to Alldayeveryday

Mandy Harris Williams is a renaissance woman working across more media than one could reasonably hyphenate. On social media, in her monthly #brownupyourfeed radio hour on NTS, and with her myriad published essays, she challenges us to consider critical theories on race, gender, sexuality, and above all, privilege. She dares us to meet the most divisive aspects of our charged political culture with a caring ethic that prioritizes those most deprived of our love and compassion. Offline, her DJ sets are like a blast of Naloxone to the automatic nervous system with the power to reanimate the rhythm in even the shyest of wallflowers. After studying the history of the African diaspora at Harvard and receiving a masters of urban education at Loyola Marymount, Harris spent seven years as an educator in low-income communities. From there, she expanded her educational modalities to include a conceptual art practice, musical production informed by years of vocal training, and a lecture format of her own dialectic design. These “edutainment” experiences are one part college seminar, one part church sermon, and one part late-night talk show with a heavy dose of consensual roasting. It’s a Friar’s Club for an intellectual, intersectional, and internet-savvy generation. These performances draw us in with their vibey bass lines and hooks before they throw us under the quietly segregated bus that we’re still struggling to rectify. Mandy and I sat by the fire one lovely winter night in Los Angeles to talk about the contours of fascism, algorithmic injustice, her latest film for the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, and her upcoming residency at MoMa PS1.

SUMMER BOWIE: How do you think that anti-Blackness expresses itself differently in Black communities versus non-Black communities?

MANDY HARRIS WILLIAMS: I think you have the categories of it, and then you have the contours of it, and the contour is more the West African phenotype. It's less viable in a lot of ways for things like respect, and esteem, for love, and largely for interpersonal value. It doesn't matter whether you're Black or not Black, you know, because there are so many phenotypes in the world of people who identify as Black. And so it's very easy to do the same shit, especially when you're trying to justify yourself in a world that feels a little bit affronting. Everybody has their shit that they're going through, and so everybody, no matter what their race is, wants to feel oppressed (laughs) and everybody, no matter what their race is, is also racist. (laughs)

BOWIE: Arthur Jafa talks about subject position a lot and the way that we're so accustomed to putting ourselves in white, male subject positions because we're so used to seeing narratives where they play the protagonists, which is why they feel so entitled to our empathy. But the same goes for the types of Black protagonists we're accustomed to seeing. There are the phenotypes that we have become accustomed to empathizing with and then there are the ones that tend to play the supporting roles.

WILLIAMS: I did a lecture and I said something about how the movie Sideways is the pinnacle of that art form when it comes to those entitlements between both race and gender. (laughs) I'm not going to say something bodyist about whether this man [Paul Giamotti] has value as a sexual object to others. But, what I will say is that I'm not going to deny that there is a market wherein “body” has real material consequences. So, holding both of those positions, there's still nothing lovable about him.

BOWIE: That's true.

WILLIAMS: And he is with these amazing women, right? And he gets the girl at the end, after doing...

BOWIE: ...Nothing for it. (laughs) The body economy has also become hyper-mobilized in the social media sphere. I'm curious how you see our algorithms working to enforce racial bias, gender bias, and ultimately white supremacy?

WILLIAMS: That's a very big question. I'll say there's a programmer bias. There's a moderation bias. There was this issue where you couldn't write like, men are trash on Facebook [without being shadow banned], but meanwhile, they just came out with this MIT research article about how Facebook was sponsoring misinformation forums—like actively aiding them.

BOWIE: Interesting. Wow.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. That's a doozy that came out in the Facebook Papers, which we haven't noticed because these motherfuckers control the way that we access information. And so, you have the issue regarding who has the resources to put up this internet space.

BOWIE: When did you start #brownupyourfeed and where did that come from?

WILLIAMS: That came from me looking at people's feeds and not seeing a lot of Brown people. You know, everybody’s talking about Black Lives Matter, and maybe they do have Black people in their life, but in this place where people are engaging in an autodiaristic practice, it’s not something that most of them are documenting or addressing. So, it does provide some sort of statement about the way you think other people value you. It would just surprise me. I would look through people's stuff and I'd be like, "Huh? Am I the only Black person getting around?"

BOWIE: You did a great lecture on nose privilege, which is something that’s often overlooked. We rarely acknowledge the role that our noses play in the doors that get opened or closed. I have one of those beauty apps on my phone that I like to use for caricaturing people’s faces, and one of the strangest things about it is the nose modifier. There's not an option to make the nose wider, only thinner. It makes you wonder where this perception comes from—that there's this one-way path to improvement?

WILLIAMS: (laughs) Right. I think it's white supremacy.

BOWIE: As a Black woman, what are some of the algorithmic biases that you have to push through on Instagram? And what are some of the ways that you employ it in order to spread your message?

WILLIAMS: I mean, I don't wanna speak too much about my particular experience, because you can never know what would've happened in your life with a different visage. So, I try to consider the general contours of what is taking place and how I might be subject to that. Or how I might not be subject to that. This gets back into that thing of everybody wanting to be oppressed and everyone being racist all at once. There is a canonical unwanted, and a canonical desired, and I don't think I'm too close to either side of the spectrum. For example, I have some privileges as far as where I'm from, how I speak, the institutions I've attended, the way I look, everything. The way I like to approach it is like, in this stream of technology and communication, has there ever been a time when oppression or bias was broken? Because we know for sure that slavery was a tool of social control. So the question is: when did that right itself? Because what really grinds the gears of fearful white people is that feeling that you're just picking it out of the sky. So, I could say I'm oppressed because of this or that, but the question I have is: when did that stop, in what stage of technology, in what economic sense? In what romantic sense? In what political power sense? You look at our run of presidents, and I guess we have had our first Black woman president for seven minutes while Biden was under, but we've never elected one.

BOWIE: What's interesting about this phenomenon of everyone denying their internalized racist tendencies is that they’re usually very quick to acknowledge the oppression or adversity they’ve had to overcome personally. Where could all this struggle be coming from if everyone were so respectful of one another?

WILLIAMS: I mean, intersectionality is the best bet, and then you have to tell the truth about the other stuff between those two things. Like a care that responds to the reality of how intense white supremacy has been and how much it has gone unbroken to this day. And then, you have to balance that with a care ethic. It's both critique and care. So, I'm gonna take care of this more, because I know historically it has been subject to more oppression and less care, and those tend to go together. One means of oppression is to not care for people, to position them as unlovable, or just invisible.

BOWIE: Right, often when people say things like, "Nobody can take a joke anymore," they don't ask who is being cast as the butt of the joke and how frequently they're cast in that role. Back in the ‘90s, bell hooks talked about the term ‘PC’ and how it was improperly framed as a way of policing rhetoric, rather than a call toward respectful sensitivity. There's this strange backlash where people are honestly asking why they need to care and why they can't willfully deny that we as humans are sensitive.

WILLIAMS: I don't even feel like backlash is harsh enough. It's just the contour of fascism. And this is a cycle. Every time there is some measure of civil rights or liberation achieved, it's followed by this backlash, so to speak, but it's happened so many times that we can see it's just a way by which the conservative powers that be can reclaim their positionality and expand it.

BOWIE: How do you feel now that it's been almost two years since the initial uprisings of 2020. We're seeing major changes in some regards, and then business as usual in others. Did it all go down the way you had expected?

WILLIAMS: The challenge of not being jaded is trying to actually believe that change is possible. I would like it a lot if there were continued emphasis on progress and change. The response has been very dispersed. Some people are staying the course, some people are tuned out and over it. Some people don't want Black people to be the center of attention anymore, or they're annoyed—just immature shit. And I don't know if I expected it to go any particular way. I tried to strike while the iron was hot, and I also feel like I've been doing it for a long time. So, it's good to have some more eyes on the things you're talking about, or people starting to be like, "Huh? Okay. Maybe there's something to those words that are intense, or harsh, or implicate me, or that I have to make some sort of change. Maybe I don't have that much spiritual or material security around my behavior.” What has really happened, though, is a lot of people have just checked out.

BOWIE: A lot of people felt like they were being asked to do a lot of extra things in their life, rather than just asking what they could immediately stop doing. Your work really teases out the very subtle ways that people express their anti-Blackness and how egregious these subtleties prove to be over time. Do you feel like you've always seen the world through this lens?

WILLIAMS: Being a Black child on the Upper West Side at this strange, progressive institution as a kid, we were always talking about social issues and civil rights. This is what people fear when we talk about critical race theory in the classroom. I had enough theoretical buckets and language to understand some of the weirdness that would happen with me. I was always like, Why am I different? What did that mean? What makes me different from most of the kids at my school? What makes me different from other people in my family? What makes me different from other Black and Brown kids? I felt different in a lot of ways. I don't think that every person with a mixed cultural experience necessarily has this pattern of thoughts, but I do think it puts you in a place where you have to deal with marginality in a way that gives it a real multi-applicable texture. It's a seasoning, like salt.

BOWIE: It's just in everything. How do you combine the aesthetics and the politics of what you do through your art?

WILLIAMS: I like to look at the ways that fascism creates climates of anti-intellectualism. So, I made this film for dis and I shared it at the Centre d'Art Contemporain in Geneva, and for me, the container of intellectualism is also one of these things. Being a Black woman, or being fuller-bodied, or being intellectual are all ways in which fascism wraps itself around my experience. So for that, I worked with this Edward Said essay, Representations of the Intellectual. It was a series of lectures he did in 1993 at Oxford where he talks about the definition and the role of an intellectual: how it’s a persona of a bygone era, and how industry and specialization encouraged those who demonstrate intellectual prowess to become marketing geniuses or programmers. It talks about the ways in which anti-intellectualism is encouraged by fascism and how not having an intellectual culture enables certain phenomena—like dog whistles—that reinforce structural racism and genderism. The film itself doesn't have a racial component to it, which is really funny. It's implied by offering myself as the filmic image, and it also talks about intentionality with the subjects we choose to address in media.

BOWIE: How did the concept of the film come about and how did you go about making it?

WILLIAMS: We were in the uprising period, maybe a little bit post, and people were looking to Palestinian scholars because of the violence against Palestinians overseas. Those two moments were nesting on one another such that you could look at an entire—not racially or ethically-specific—politic of the subaltern, or the “other.” In that moment, lots of people were looking to theorists like Said, because of his ability to express this general condition of politically marginalized people. But I gravitated to one of his lesser explored works and I was using that as a means to understand how critical thinking, writing, theorizing—intellectualism, generally speaking, is a part of a protest and liberation tradition. I took a lot of solace in understanding what my position was. It sounds a little bit arrogant to say you're an intellectual, but part of my process with listening to this work was trying to understand where I fit into all of this. I'm not out on the streets. I'm not organizing in a traditional sense. Why is my voice important? Is this navel-gazing? Is it selfish? Is it bourgeoisie? And I felt really validated. It also gave me a roadmap for what sorts of interventions are important for me to make. Things like talking about intellectualism in an era when it's so clear that critical race theory has become the maligning of woke, which is ultimately about Black enlightenment. And I can see how those things being maligned has this particular contour that allows for fascism to pervade, and anti-Blackness to take place in a time when it's really needed by some people. They are clinging to it, and to circle back, you can see it play out as a form of algorithmic injustice. You hear about these Facebook Papers and how they're actually farming misinformation. It's a pretty damning look at how all of these systems are working together to control the way information is distributed. So the film is a protest gesture, located at a corner of the work against fascism as I see it right now.

BOWIE: You recently did a performance lecture at Oxy Arts, which is a public art space rooted in social justice. This was for the closing of their Encoding Futures exhibition where artists that work in AI and AR proposed more just visions for the future. Do you see any immediate ways that we can improve technology to make it less fascist?

WILLIAMS: That's a great question. In order to make anything less fascist, we really have to—on some level—become less fascist, right? For example, this soda can [points to La Croix], we don't know who the manufacturers are, or where the factory is, who owns those means of can-making, who's profiting most off of the can makers' labor? And then, what's the likelihood of those can makers being X, Y, or Z ethnicity, versus other tiers of the can industry?

BOWIE: Sure. Who's mining the aluminum?

WILLIAMS: Right. The thing that keeps me encouraged, or not terribly depressed, is that I can be athletic and a little scatterbrained about whatever my intervention is gonna be. Because I'm not gonna state the same thing over and over again. I refuse. So, broadly calling myself a conceptual artist or believing in myself as that, or believing in the interventions that come of that is based on trying to come at it from many different angles. In the way that a teacher has to come through many different modalities. You have a phonics song, and then you have phonics movements, and then you have phonics posters. I don't really want to specialize. I could get a PhD, and I'm not saying that wouldn't be fun at some point in time, but there's also this increasing jargon the more you get specialized. So, I like to use media like film and music. I've been really great at writing music recently, and it's exciting, but the music comes really easily and I like the idea of the container of the rock star, or the pop star. It's an entertainment class whereby Black people have far more esteem or prestige than in other spaces. Tons of influence. Nikita Gale, is an artist who I had the pleasure and privilege of talking with in a couple of structured formats, and she talks about how performance inspires her work, but she's interested in playing with how performance can be not of the body. And my takes are all very bodily. There's always this very embodied measure of my spoken word. It's always a lyrical didactic, and that's the prism that everything's going through. So, whether it's film, documentary, or maybe you have some voiceover, or essay, or music, I really just enjoy using my voice. I don't think there's a category for it, but I sometimes call myself a vocal artist, because it's all about this embodied resonance.

BOWIE: That’s a perfect way to put it. Your lectures really do transcend the standard format in a very unique way. A critical theory may be expressed in all seriousness, or it may be done comically in a way that just comes out and bites you (laughs), or it becomes a song and dance. It hits our bodies in different ways, it hits our feelings in different ways, and it's a communal experience. You're almost like a preacher, but the experience is this cross between church, a talk show, and a college lecture. So, what else do you have in the works this coming year?

WILLIAMS: I’m really excited to release more music this year and play with the format of musical performance, and recording. I’ll be working with my long-time dance music family, A Club Called Rhonda, for those releases, and that music is a text that will fold into the performative lectures, as the Oxy lecture did. I have a residency at MoMA PS1 from February to May, and what I'm really excited to do is take the format of that Oxy lecture and expand on it, because as I was creating it, I was like, "Oh wow. This is the pocket." This is a place I could stay and move the focus ever so slightly to make a repeating series of work. My best friend, Paul Whang was the production designer, my sister Yves B. Golden was the DJ, and I just really loved making it with my friends. It's real bliss work. I'm also touched by Audre Lorde's essay, Uses of the Erotic, because at the crosshatch of the lecture that I performed at Oxy and what I'll be expanding upon for the PS1 residency is the spiral of how the critical and the erotic feed one another as a source of wisdom. Part of the reason I talk so much about the right to be loved or considered beautiful is because while they might seem less important than something like civil rights or economic equality, there are these soft rights that through social design become instantiated as rules regarding who should earn what based on how they look, and then how they might be loved or cherished.

BOWIE: I think that essay should be required reading for all high schoolers. There's a lot to be said about the systemic repression of the erotic, particularly in women, and even more for women of color, because of the power that it holds. Likewise, it speaks to what you were saying about it sounding arrogant to say you're an intellectual. Regardless of one’s gender, we’re often made to feel shame for embracing what feels like the fullest expression of ourselves. Can you tell us a little more about what those lectures will explore?

WILLIAMS: I'm going to be working on a suite of music and lectures that deconstruct the blues origin story. The first, I think, is about sonic Blackface, the second is about the lightening and depoliticizing of the blues mama archetype in film and music, and I don't know what this third lecture is about, but I think it's called Dances with Dolezal. (laughs)

BOWIE: I mean, Billie Eilish needs choreography to accompany her tunes, doesn't she?

WILLIAMS: Yeah. The note under that is “gestural/auditory Blackface.”

BOWIE: It's as though we need to give certain white celebrities the permission to take on these contours you refer to of the Black persona so that we can give ourselves the permission to continue appropriating as well.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. That's what @idealblackfemale is about. It's a reclamation of me taking on a persona. I like to think of it as assholery a little bit. The nomenclature of the whole thing is meant to be a little bratty, you know?

BOWIE: It feels like a very clear response to the way that Black women are discouraged from being as cheeky as they wanna be, or as salty as they wanna be for fear of sounding bitter. And why? White men get to bitch and moan about every little inconvenience.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, there's this funny debate about the term incel and which community it really comes from. There's a line of argument and study that says it actually comes from Black women who are among the least married populations in the US—along with Asian men—and are both structurally and desirability-oppressed.

BOWIE: Right. They like to claim that the violence of the incel comes from the fact that he's not getting laid, which is his “natural right,” but are young, white men the least laid people?

WILLIAMS: (laughs) There are a lot of other populations that are structurally less laid.