Love Is Not All directed by Kimberly Corday and Kate Biel

interview by Eva Megannety

In fashion, desire is often draped in fabric, but for Kate and Kimberly, it lives in motion. In their collaborative short Love Is Not All, the two artists trade runways for reels, channeling longing, beauty, and decay into a filmic fever dream. Against the backdrop of a world increasingly obsessed with speed and spectacle, their work feels like a deliberate pause - a place where emotion lingers, glances haunt, and the act of getting dressed becomes a cinematic ritual. As fashion continues to merge with entertainment, film has become the new frontier for designers looking to craft legacy, not just collections. For Kate and Kimberly, fashion isn’t just about fabric and fit - it’s about emotion, storytelling, and cinematic escapism. And through their lens, each frame becomes a love letter to the art of getting dressed. We spoke about the allure of the fashion film, the seduction of storytelling, and why, for them, desire can only be truly captured in movement.

EVA MEGANNETY: Can you both walk me through the inspiration behind Love Is Not All? How did Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poem shape the vision for the film?

KATE BIEL: Okay, so it’s sort of an extension from the first shoot I did with Kimmy, a couple of years ago. I think it was 2022. It centered around these somewhat sinister, feminine archetypes, isolated in a black void. It felt like a commentary on the ostracization and alienation that stems from feminine hunger and desire. Like Kimberly’s garments, it’s a feeling that’s both ancient and modern. We wanted to explore that further because we felt like we were onto something.

KIMBERLY CORDAY: It’s interesting that the poem led us to the film, but once we had the visuals in front of us, our initial idea of using voiceover to recite the poem felt like overkill. Watching the dailies gave us the same feeling as the poem.

MEGANNETY: How do you both feel the film captures the essence of the poem? How did you approach translating such a powerful literary work into visual art and fashion?

BIEL: Kimberly and I both have such a personal connection to this poem, it resonates with each of us in similar but different ways. For me, it encapsulates all the love stories that have really stuck with me: Phantom Thread, The Beast in the Jungle by Henry James, or even my own relationships. I've always seen love as tragic but necessary - nothing transforms you like romantic love. It’s overwhelming, humbling, a constant ego death. Torturous, but it’s also how I’ve grown the most, personally and creatively. In the film, we wanted to explore that duality, love’s destruction and its fertility, through each vignette.

CORDAY: When we were first discussing the short, I had kind of given up on looking for love. But I’ve always been a romantic at heart, so I was constantly grappling with those two sides of myself. This poem was kind of like my single woman manifesto because it encapsulated that same feeling through a combination of flowery language and macabre imagery. And the irony is … I met someone while working on the short.

MEGANNETY: Did that change your view on the project?

CORDAY: Yeah! In pre-production, I actually consulted him about the budget because I’d never handled a short film before - I’m not a line producer, so I really didn’t know what I was doing. And now, we’re literally engaged.

MEGANNETY: Oh my god! That’s insane, congratulations. What a beautiful full-circle moment.

CORDAY: Thank you!

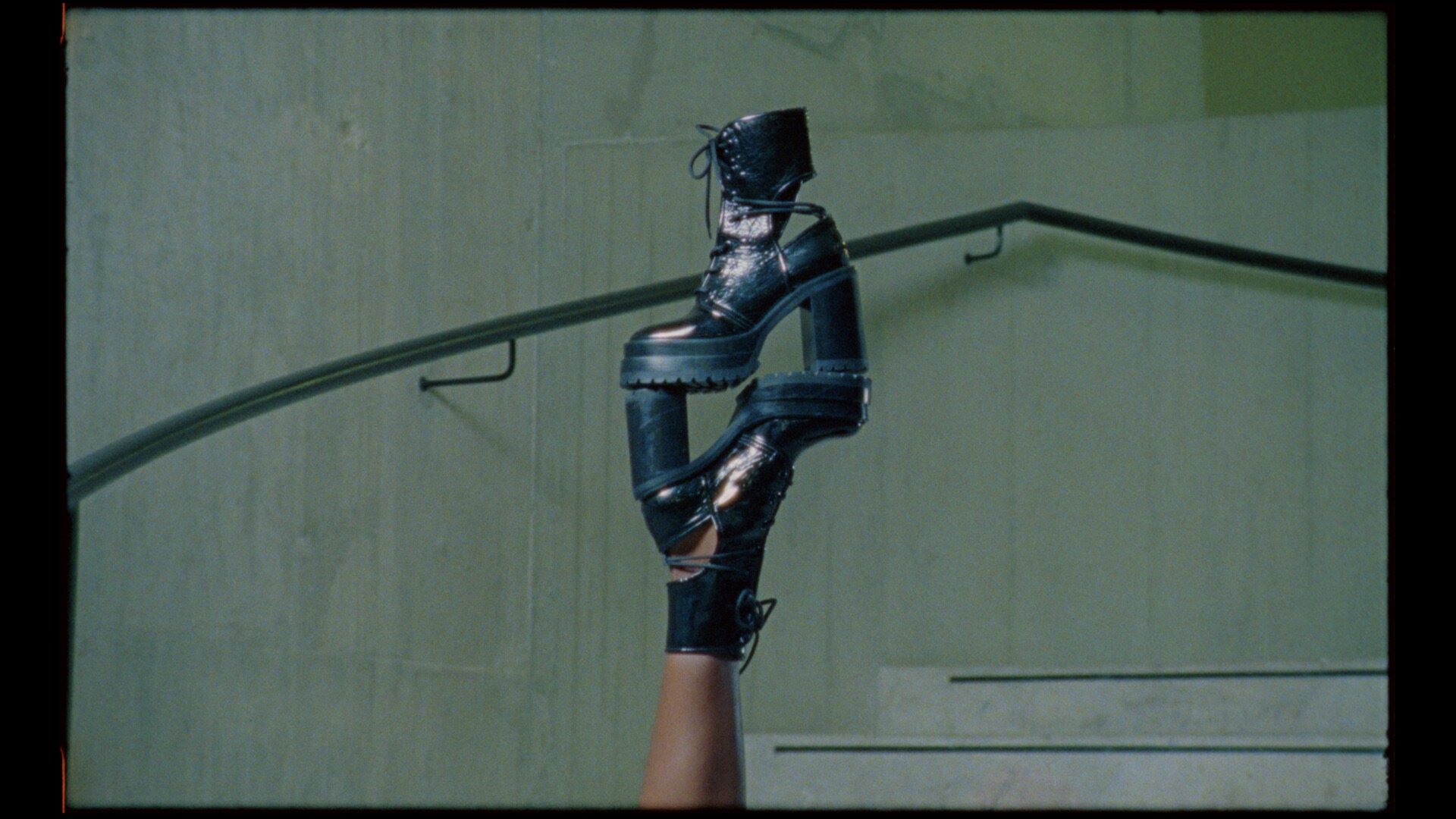

MEGANNETY: Kimberly, your brand is known for merging punk aesthetics with a softer, more feminine touch. How did you blend these elements in the film’s character design and overall art direction?

CORDAY: Well, I never explicitly set out to make things that are both pretty and punk. I even fought that instinct for a while because I was afraid of being boxed into a genre. But I guess it’s just in my nature; it’s what I gravitate toward when I create.

MEGANNETY: The film seems to feature a lot of gothic undertones. How did the gothic genre influence the design of the wardrobe and visuals?

BIEL: Totally. I think the gothic genre is something that both Kimmy and I have always been attached to. For me personally, I love the erotic melancholia experience in Victorian era romance. There was this dying for love and being seen and being worshipped, but also was just not a fun time to be alive in, you know? And so, I think the gothic genre does a perfect job of challenging the romanticized, over-idealized notions of love. It adds these elements of fear and haunting to the mystery of human connection. And we wanted the visuals to be reminiscent of a ghost story, which is like unsettling yet bewitching, just like being in love.

CORDAY: Echoing what Kate said, I really love the gothic genre, so it comes up unintentionally in most cases. And so this time I thought, why fight it? Let's delve deeper into this. We were looking at a lot of medieval art and early horror films like Jean Cocteau's rendition of Beauty and the Beast from 1946, and just let ourselves play in that world and have fun with it.

MEGANNETY: Desire is often a central theme in both fashion and storytelling. How does Love Is Not All explore the idea of desire - whether it’s longing, obsession, or the pursuit of something unattainable?

BIEL: Yeah, I think we grounded that theme really clearly in the lead’s journey, the way the film begins and ends. With desire, there’s always this element of danger and risk. You have to give yourself away entirely, and there’s just a lot of risk with that loss or gain, because you could entirely lose yourself in that. And so in the first scene, our lead enters this portal through consumption, and she’s honoring her hunger for more while still being uncertain if she’ll come out on the other side fully intact. And I would argue that we’re our most feminine when we allow our desires to take control and overpower our reasoning, our logical thinking. It creates something scary and uncomfortable, but also violently beautiful.

MEGANNETY: I love that analogy. The film has an ethereal, almost dreamlike quality. Do you think desire is something inherently surreal or unattainable in some way? How does this influence your artistic choices?

CORDAY: For as long as I can remember, I’ve been a fantasy addict, like growing up, I was obsessed with the artist J.W. Waterhouse, who painted pictures of nymphs and Roman Gods and sorceresses. I never wanted to leave that world, and honestly, I still haven’t. It makes reality a little easier to manage. Escapism plays a huge part in my brand’s aesthetic. Kate and I were referencing a lot of the surrealist painters like Paul Delvaux and Leonor Fini, whose works very much feel like a fever dream. So I’m happy to hear that translated.

BIEL: Totally. The vignettes start with this idealized version of love and romance, but as the film progresses, those fantasies start to crack. We wanted to show the inner conflict of desire - this constant dance between fantasy and reality.

MEGANNETY: Fashion is so intertwined with desire - whether it’s being seen, expressing yourself, or embodying something else. How does your work tap into the psychology of desire?

CORDAY: I feel like right now, people are hungry for romance and eroticism. There was an article a few years ago called Everyone Is Beautiful and No One Is Horny, about the simultaneous fetishization and desexualisation of the body on today’s screen. I’m hearing desire in a lot of new music, especially pop, but it feels like film and visual arts are devoid of it right now. Kate and I grew up on Steven Meisel editorials, McQueen and Galliano runways … we want to bring that tension back, that tug-of-war between romance and something more lascivious.

MEGANNETY: In an era of fast fashion and fleeting trends, how do you think desire influences consumer behavior in the fashion world? And how do you both navigate that in your work?

BIEL: We both have similar, but different approaches given our medium. But personally, I try to slow myself down and remind myself that desire can be achieved through scarcity as well. That being selective, thoughtful, and precious in producing my work versus working from a quantity over quality mindset ultimately does a better job at serving myself and the audience. And that it’s sort of just like comparing casual sex with love and passion.

CORDAY: Yeah, I’ll echo what Kate’s saying there. I’m personally interested in romance, not pornography. And I want to create things that haunt you or make you desperate to seek out, almost like an unrequited crush. Pornography is immediate and disposable. Romance is about withholding, delaying gratification, which is the sensation that I’m interested in recreating in my work.

MEGANNETY: I love that. Fast fashion is like pornography. So accessible in today’s world too. It’s a shame. Do you think the pursuit of artistic creation is driven by desire? If so, what kind of desire fuels your work?

BIEL: I would say my work is honestly only driven by desire to really get down to brass tacks. Like my desire for approval, my desire to feel something, my desire to be seen, my desire to be understood and to understand the people around me. Desire is just exhausting, but also the only thing that gets me out of bed.

MEGANNETY: Yeah, I really relate to that.

CORDAY: To be honest, I have no idea why, but it feels like I was bit by some bug that keeps me up at night creating and doubting myself and starting and stopping projects. It’s just in me and I follow it because it’s better, or somehow less painful than the alternative.

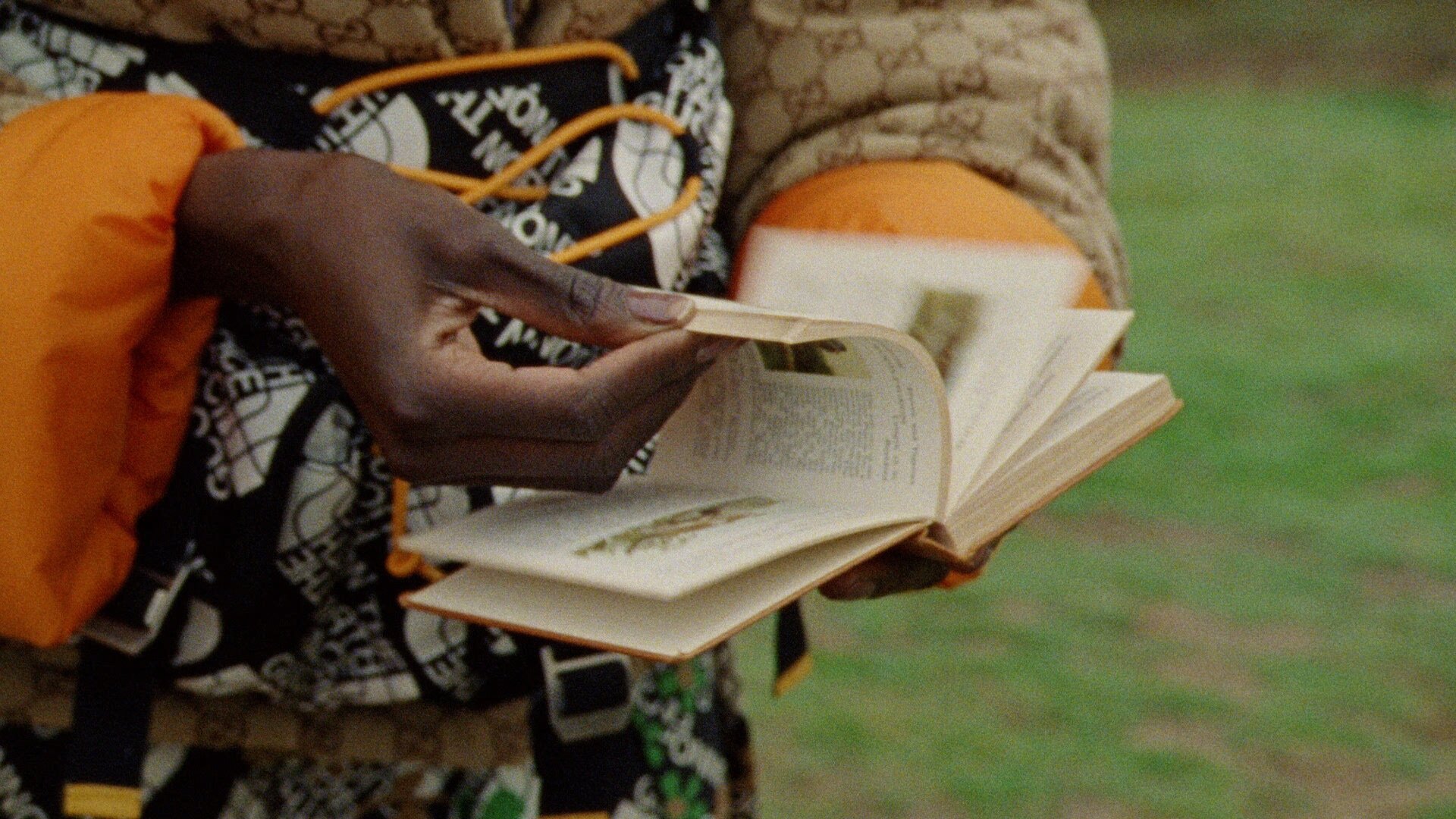

MEGANNETY: Your process involves manipulating materials like old lingerie and boudoir remnants. Can you explain how this Frankensteinian approach plays a role in the storytelling of the film and fashion pieces?

CORDAY: You know, the making of this film didn’t really change my process, it’s pretty much the same whether I’m creating for a stockist or a performance. But, what I can say is, any time I make something, I come up with characters who might wear what I’m working on. In this case, I had outlines of vignettes and Kate’s input to help build out the characters.

MEGANNETY: So you had the garments first, and then the characters kind of grew from there?

CORDAY: Kind of. I made the garments based on the ideas Kate and I came up with for each vignette.

MEGANNETY: Fashion films are such a captivating way to showcase a brand’s narrative. Why did you choose to tell the story through a fashion film rather than traditional runway presentations or photography?

BIEL: When Kimmy and I first started, we were watching so many films where fashion was the heartbeat. One that really stuck with me was a documentary on Helmut Newton. There’s this incredible moment where Charlotte Rampling is being interviewed about modeling for him before she became an actress and she was saying that with modeling there’s this kind of frustration that comes about a still photographic session and it’s almost like you’re on the point of a climax and you’re stopped all the time and you’re frozen and your energy keeps coming up, it keeps coming up but it has to be still.

And while in film, that climax moment is really lived in - fully realized and honored - I think that’s why we have a handful of these scenes in the film with no cutaways. We linger on the subjects, lavish in their desire, to the point where it feels almost extravagant. And so I would argue that desire can only truly be represented through motion.

CORDAY: I was going to say, I think there’s a story built into my personal work and Kate’s personal work. Someone, upon first meeting me, told me that my brand brought up visuals of a 17th-century Versailles woman having a mental breakdown, which I just love. The stories are already there, they’re just waiting to be expanded on. And a fashion film felt like the natural next step for my work.

MEGANNETY: Kimberly, your brand has been described as walking the line between “punk” and “unapologetically pretty.” How do these contrasting elements work together in Love Is Not All, and what does that duality represent for you as an artist?

CORDAY: Yeah, I like to think it’s just an extension of my personality. I’m overly polite with a trucker’s mouth. And I listen to Vivaldi and Minor Threat in the same sitting. I think the contrasting elements in my work, the ultra-feminine and the unexpected decay are just a natural expression.

MEGANNETY: What do you hope viewers will walk away thinking or feeling after watching Love Is Not All? Is there a particular message you want to convey through the film’s narrative and visuals?

CORDAY: I would like to haunt someone. I don’t need the viewer to understand what they just watched. I just hope that they walk away with a distinct feeling. And I hope it’s not a passive viewing. That’s the effect that LEYA’s work had on me throughout the editing process. I was haunted by the score that they made for the short.

BIEL: Yeah, I’d kind of say the same. Kimmy and I have this love relationship through our collaboration, we’ve gone through so many eras of creativity and ideas. And this film is sort of a tailing off point from the first photo shoot we’ve done. It kind of shows that love is this open project, and there’s no big end. And it’s not necessarily romance, but it also shows that creativity is erotic in and of itself. So yeah, it’s about the many ways we, as creators, explore eroticism, desire, and love, and how it’s never-ending. A constant, open discourse.