text by Lara Monro

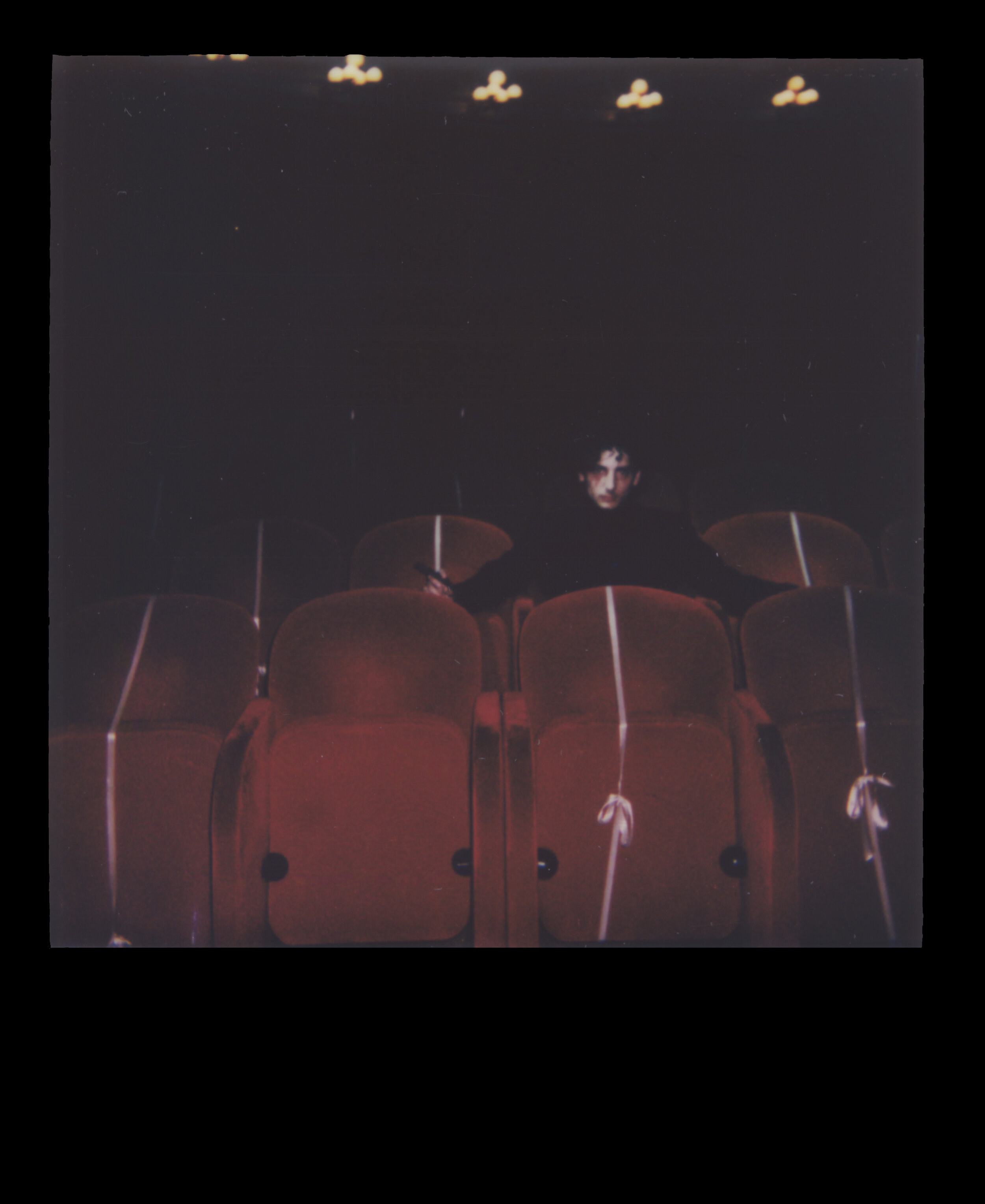

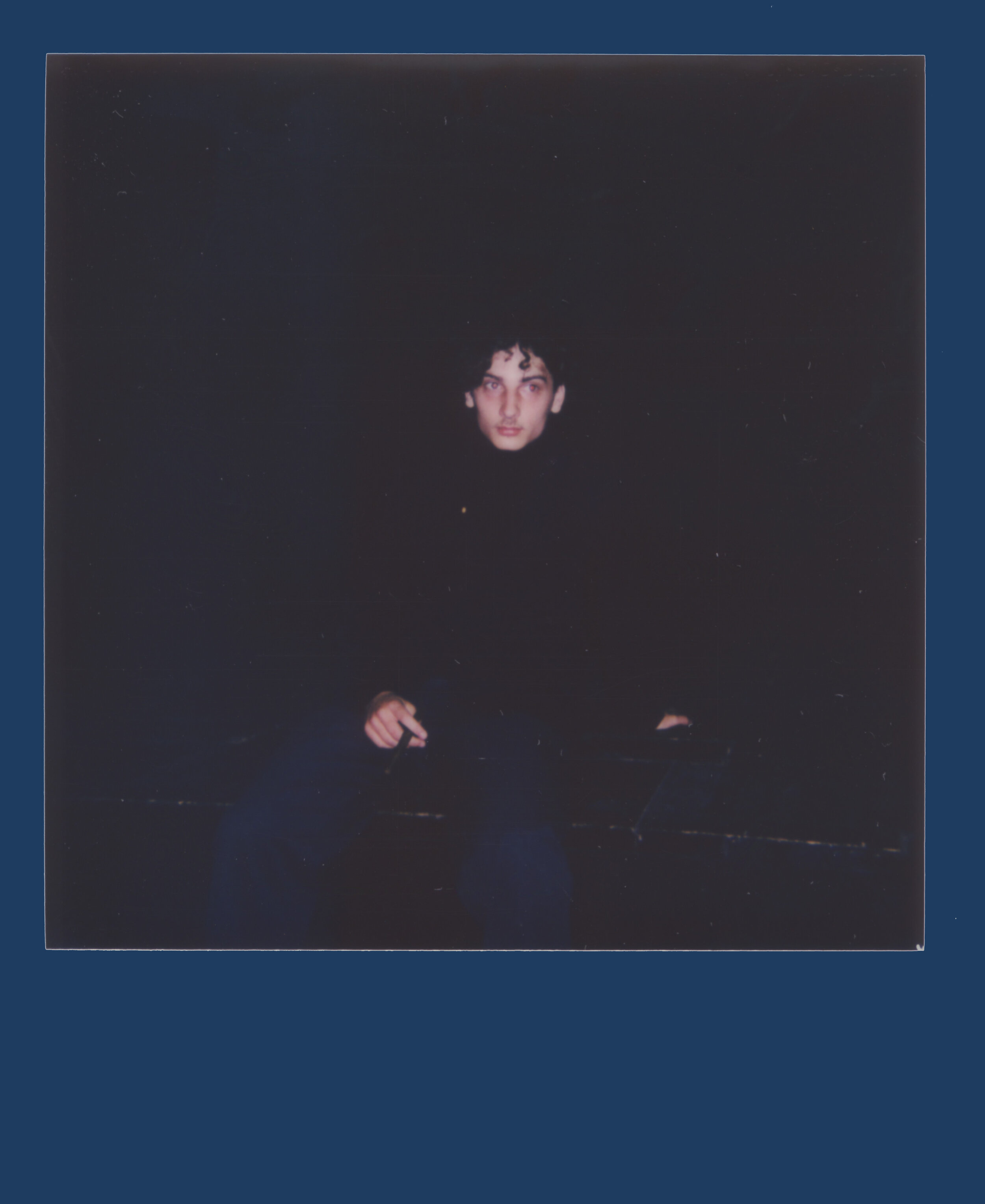

portrait by Brynley Odu Davies

Charlotte Edey is a London-based visual artist who adopts a multidisciplinary practice as a form of personal and political expression. Drawing on a multitude of themes, her work addresses notions of femininity, gender, body politic and mythology. Edey’s tapestry, embroidery and sculptural pieces are extensions of her drawing practice, and her distinct artistic language focuses heavily on symbolism and the investigation of space. Recognized for their surreal dreamscapes and pastel palette, she employs a recurring water motif that takes inspiration from Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” which serves as an investigation of ‘hydrofemininity,’ and the belief that our bodies are fundamentally part of the natural world.

Edey’s newest body of work, Framework, is currently on view at Ginny on Frederick. In this exhibition, a dialogue between each piece has been created by the artist as she examines various ways to blur the boundary between the real and the represented through the motif of the window and frame. Using these as a point of departure, she explores the notion of transparency to identify and differentiate between interior and exterior, public and private. Her intricately detailed—hand sewn and beaded—tapestry works and larger mirrored pieces are symbolic gateways that gently interrogate interior space, identity, and observation. We spoke on the occasion of Framework’s opening to discuss her development in recent years, as well as her interest in the symbolic interplay between windows, frames, and eyes.

LARA MONRO: You attended The Drawing Year at the Royal Drawing School from 2021-2022. How instrumental do you think this period was for your development as an artist?

CHARLOTTE EDEY: Interestingly, I feel like The Drawing Year allowed me to really consider the relationship between drawing and embroidery in my work. Alternating between observational drawing classes and textiles, I was considering the role of mark-making in embroidery. Satin-stitch embroidery has such a direct relationship to hatching and even blending; layering colors to create tone. Similarly, beading feels like a stippling process. Forging this relationship has made me more ambitious with my embroidery and the works really feel like they now inform the other.

I was studying during the Covid-19 lockdowns, and I think the restrictions of that time leant a real introspection to my experience. I had some wonderful teachers who really pushed me to contextualize my instincts in drawing. I started working primarily in soft pastel as I’m interested in a sort of unnatural light, and pastel is such a generous medium for a glow. As a lot of my subjects are anthropomorphic, I find an uncanny luminosity lends a kind of autonomy, or agency, to subjects that aren’t always explicitly figurative.

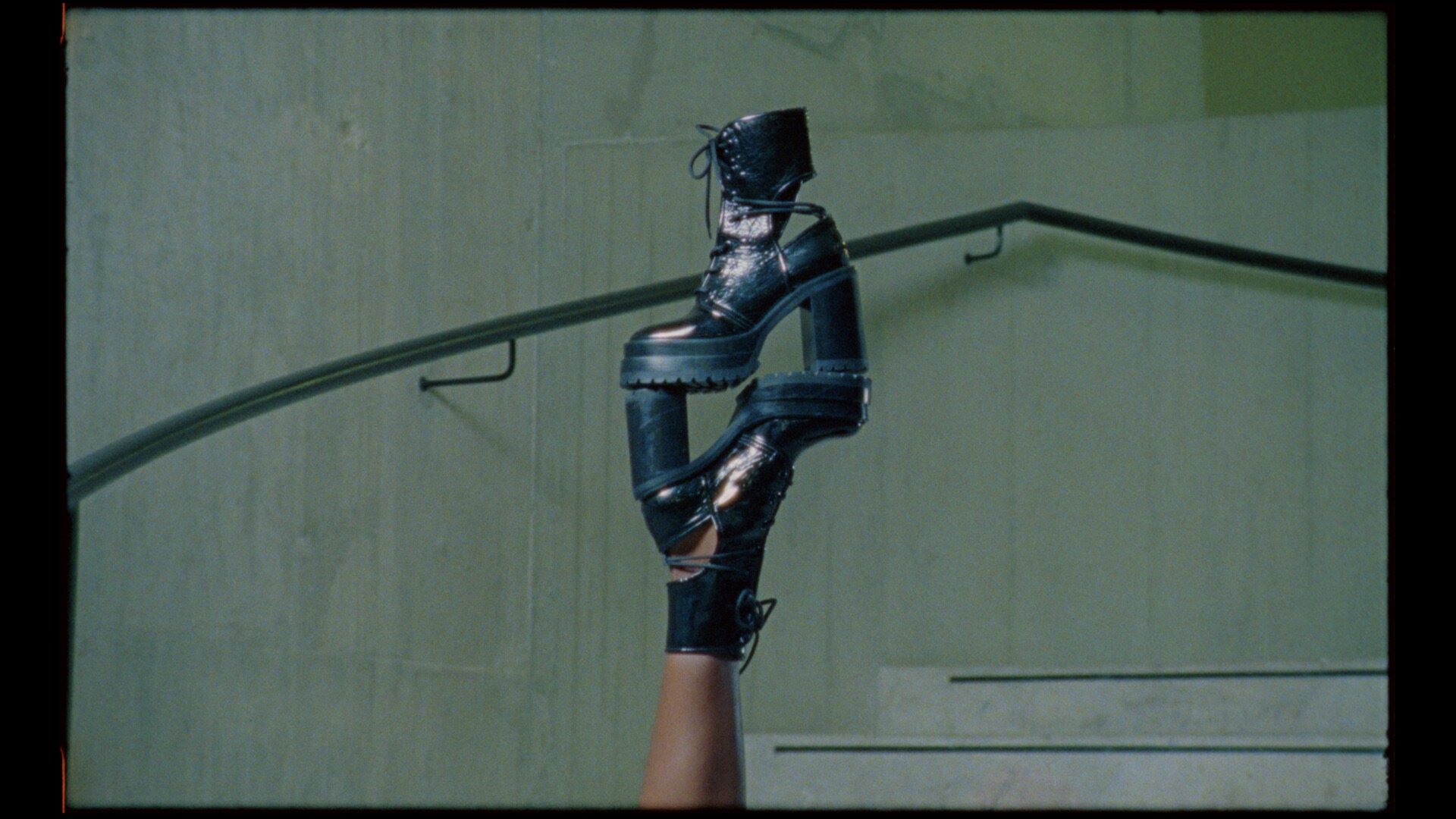

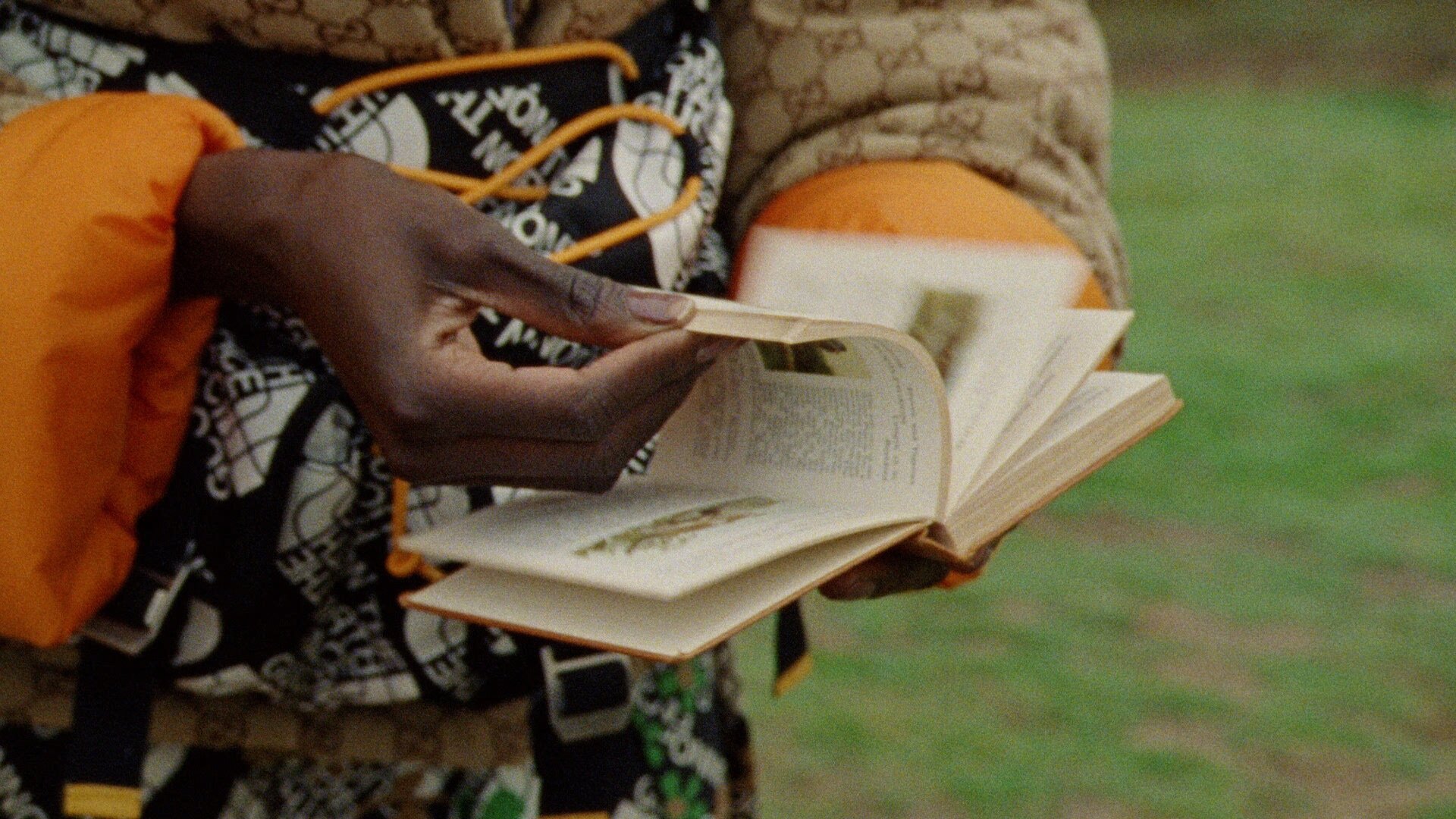

Installation photography by Stephen James. Courtesy the artist and Ginny on Frederick.

MONRO: You have started to work in very interesting ways with frames; both bespoke and found (often antique). Can you tell me about this new artistic line of inquiry?

EDEY: There are recurring motifs in my work of mirrors and windows as portals to these imagined landscapes. The first bespoke frames were made on The Great Women Artists residency curated by Katy Hessel at Palazzo Monti in 2019; a series of tapestries exploring the transcendent image that referenced the altarpieces in the Baroque churches of Brescia.

I feel like these methods of display provide an immediate context to the works they house by employing the pre-existing narratives of these objects. I really enjoy the collaborative nature of working with found objects. They are their own archetypes which deeply inform the textiles and drawings, and they imbue them with a sense of both location and time.

MONRO: Your upcoming show at Ginny on Frederick is titled Framework. Can you talk about the importance/relevance of the frames within the context of the exhibition?

EDEY: I was interested in interrogating the role that framing plays in my practice for this show. Consequently, Framework takes the motif of the window as the point of departure for a series of works exploring the potency of the window as a symbolic portal. The motif of the window by virtue of its transparency, its flat dimensionality and its frame, is predestined like few other motifs for fundamental reflection on the image and the process of seeing.

Installation photography by Stephen James. Courtesy the artist and Ginny on Frederick.

There’s a passage in Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City[: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone] I often revisit where she states that “windows are thought to be analogous to eyes, as both etymology (wind-eye) and function suggests.” This symbolic interplay between windows, frames and eyes seems the perfect avenue through which to create works that explore interior space and identity.

MONRO: It seems you are beginning to adopt a more immersive approach in the way you exhibit your work. Take the window pieces in Framework, for example, which feel more like installations. Is this something you are looking to explore further?

EDEY: The process of seeing is so integral to the visual symbolism of the window, it felt essential that the works reflect each other, creating an exchange of looking within the space. I was conscious too of responding to the ceramic tiles of Ginny on Frederick. The framework of the grid forms the underlying structure of both the tapestries themselves and of the panel sash windows that house the drawings. The grids recurring and reflecting throughout the show feels immersive and deeply specific to this space.

MONRO: For Framework you have created beautiful woven jacquard tapestries which you have hand sewn with intricate pearls and glass beads. Can you tell me about this process and where your inspiration came from?

EDEY: I was considering the role of glass within a window frame. In lieu of a sheet of glass, I wanted to cover the surface of the tapestry in a layer of glass through extensive hand-beading, akin to rainwater on glass panes. There are well over ten thousand beads across the tapestries! The beading is most dense in the highlights, with opalescent, transparent and pure white beads and irregular freshwater pearls creating a luster that echoes the bright light of the drawings. I really enjoyed working into the folds with metallic blacks and dark greens, so even the shadows glimmer.

The exhibition is accompanied by the most magical original text ‘Soft Pastoral’ by poet Ella Frears, which opens with the line: “The beads collected on the surface like condensation.” The connection she draws between the beading and beads of sweat adds a bodily dimension to the works that I just adore.

MONRO: You are using the tapestry works to examine the window as the point of intersection between interior and exterior space. Can you tell me more about this?

EDEY: Deleuze discusses the transparency of the window as enforcing “a two-way model of visuality: by framing a private view outward—the 'picture' window—and by framing a public view inward—the 'display' window.” The works in the show are divided by these two realms of public and private, exterior and interior.

The embroidered tapestry works navigate a controlled visibility. In these intimate ‘display windows,’ the curtains are drawn to the public stage, blurring the interior. The glass beads and freshwater pearls cover the surface, further obfuscating the act of seeing. Conversely, the idea of transparency and observation permeates the drawings in the show. Through the corporeal ‘picture windows,’ the sexual symbolism of spatial openings is explored. Signifiers of embodiment—eyes, mouths, loose sheets—wink and whisper across the anthropomorphic landscapes.

MONRO: Where will you be exhibiting next and do you have any plans to make new work?

EDEY: I will be exhibiting a new series of works alongside Gal Schindler and Alexandra Metcalfe with Ginny on Frederick at NADA, New York in May. After that, I’m very excited to be working towards a two-person exhibition with Azadeh Elmizadeh at Seaview in Los Angeles and an exhibition with Eigen+Art Lab in Berlin later this year.

Framework is on view through April 22 @ Ginny on Frederick 91-93 Charterhouse St, Barbican, London

Installation photography by Stephen James. Courtesy the artist and Ginny on Frederick.