Text by Paige Silveria

Photographs by Ryan McGinley

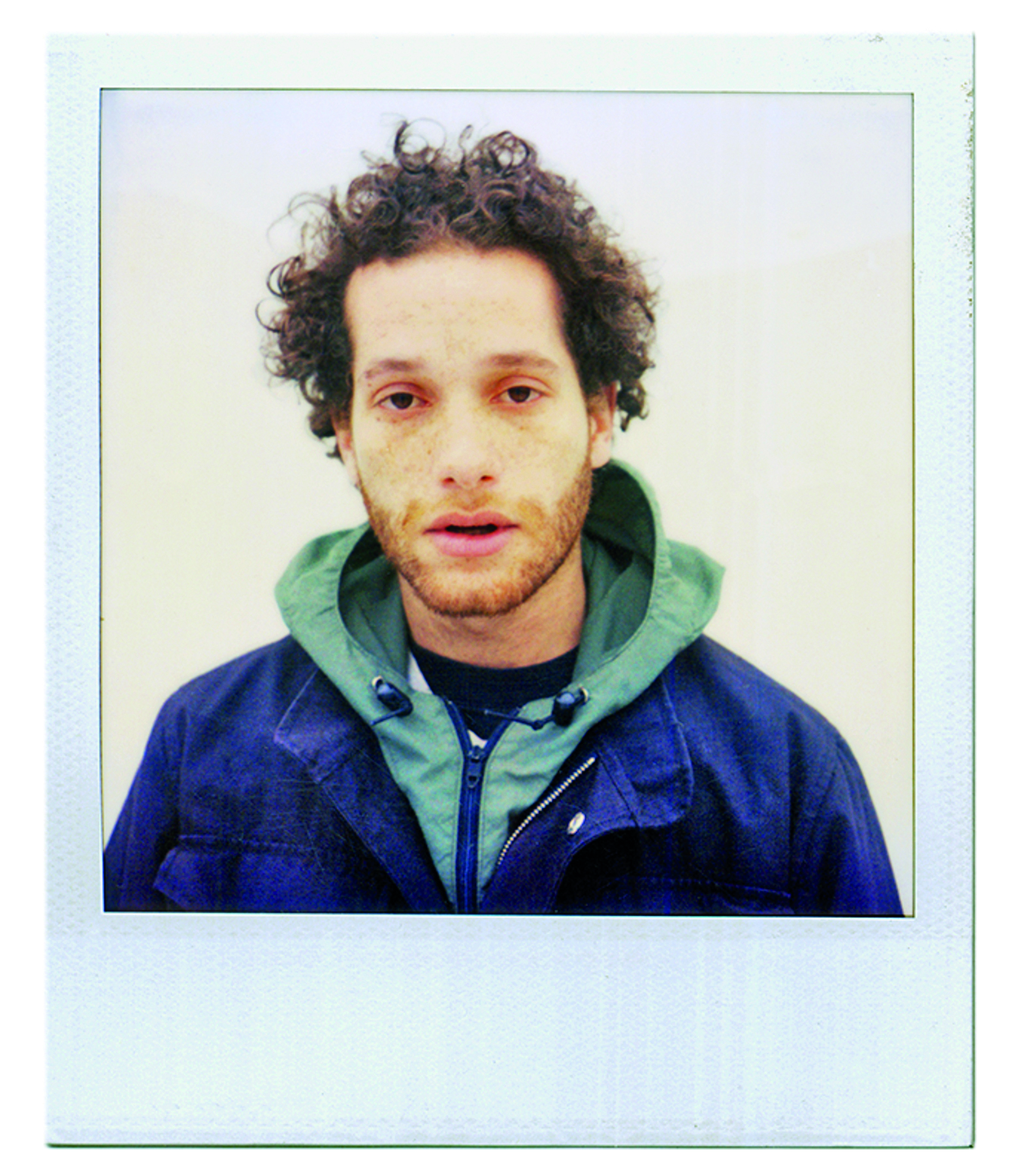

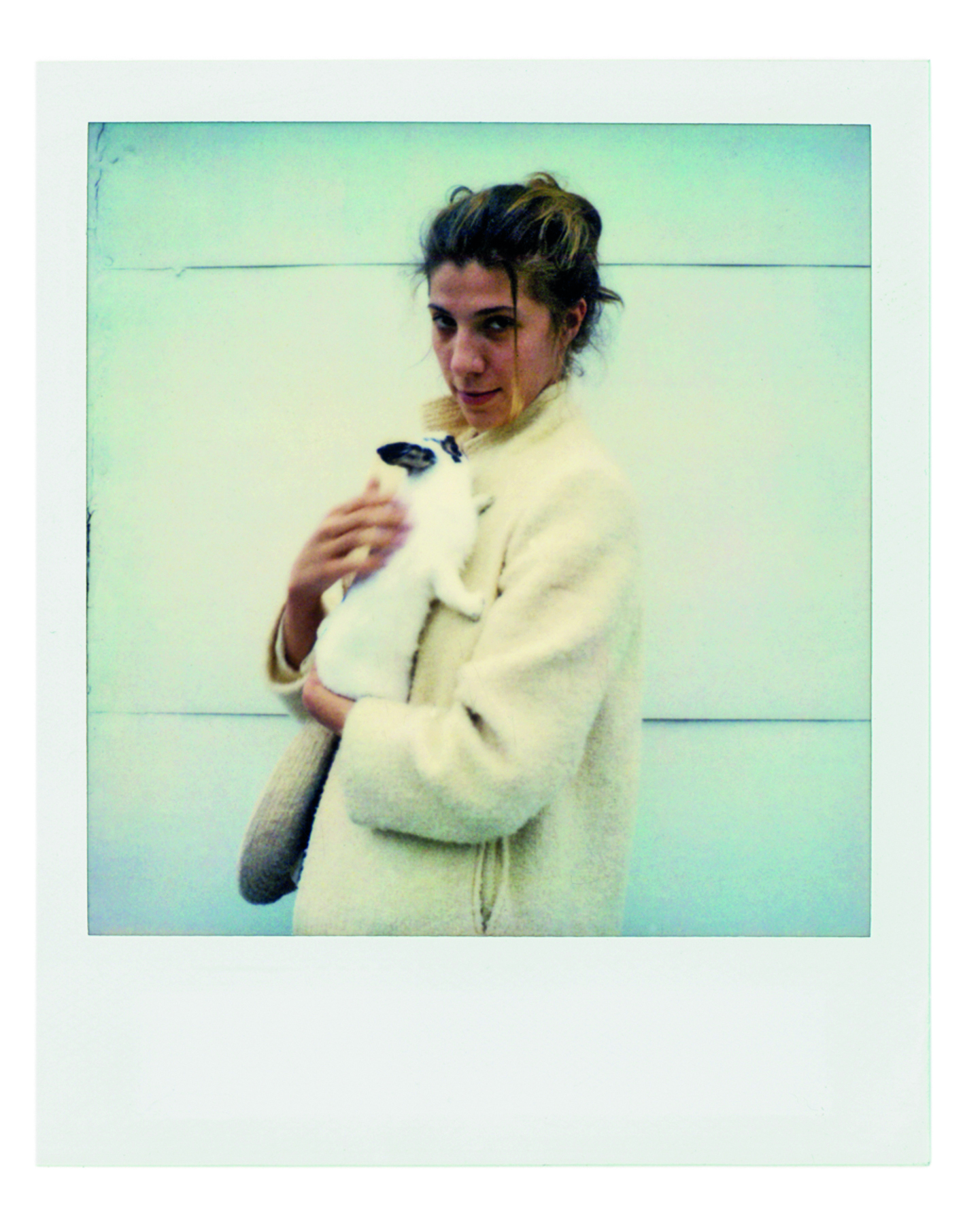

Almost a decade and a half since his documentary style photos of his debaucherous Downtown New York friends were presented at the Whitney Biennale, RYAN MCGINLEY has dug through his archives, much of which he hasn’t seen since 2003, for his upcoming show “The Kids Were Alright” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. Accompanying imagery from the initial exhibition, never-before-seen Polaroids of friends in his home over the course of four years are mixed with assorted objects and ephemera – including a series of cameras that he regularly threw up on. Knowing much about his work and its evolution since this early show, but little about what brought him there, I rang up Ryan recently to chat.

PAIGE SILVERIA: How’s your day going? Do you have a tight schedule?

RYAN MCGINLEY: I always have a tight schedule. I always have a million things to do. Like, I’m trying to prepare for this show. That’s taking a lot of energy. But it’s good! We have a book coming out with Rizzoli that I’ve been working on until the last minute. There’s a lot of stuff that you wouldn’t think of. There’s a lot of ephemera in the show, like journals of mine from that time, cameras, early zines that I made -- stuff like that. And a lot of stuff from people who were around at that time, like Dash Snow and Dan Colen’s artwork.

Tell me more about the ephemera.

Well when I was shooting back then, I was using the Yoshica T4. I went through maybe 20 of those over the course of like six years. I would do this project where I would drink Ipecac syrup, the stuff that you give babies if they eat poison berries or something, and it makes them throw up. I had this project where I would puke on my cameras. I would shoot a roll of me drinking the stuff and then vomiting on the camera. There are a few of these photos of me puking in the show. A lot of the cameras would break because of that.

What gave you the idea to do that?

I don’t know. I was just out one night and I got really wasted and I was probably throwing up and I thought, ‘Why don’t I throw up on my camera?’ I probably got the roll back and thought, ‘Oh wait. This is a good idea. It’s interesting and something I’ve never seen before.’ The camera is featured as weatherproof, which means that you can get it wet, but you can’t submerge it. So I thought, ‘I could puke on these cameras and I bet they won’t break.’ So I did this for a year or two and made a whole series. There’s a lot of broken cameras in the show.

How long have you been working on the show for?

Maybe nine months. I met the curator about a year ago. I was in Texas at Marilyn Minter’s retrospective at the contemporary art museum there. Marilyn is one of my closest friends. I went down there and I met Nora Burnett Abrams, who’s the curator for my show. When I got back, she reached out and told me about this Jean-Michel Basquiat show she was doing on the first floor. It’s only his early work. Work from when he was the same age that I was when I was making my early work, which was in the Whitney show. She asked if I’d be interested in showing my early work as sort of a comparative to Jean-Michel’s. And of course I said, “Sure, it sounds amazing.” I think there are a lot of similarities between the two of us. I think someone attending the museum would be interested in both of our work.

When was the last time you looked at that early work?

I’d never really gone through that work since I shown it between 2001 and 2003. So it gave me this opportunity to dig through my archives -- especially my Polaroids. I had this obsessive Polaroid practice where I’d shoot everyone who came over to my house. My house was sort of a flophouse at the time. I took several thousand over the course of five years or so. It was cool to go through them and my archives in general. I shot pretty heavily in that period, like five-to-ten roles a night for pretty much five years.

What was it like to go through those?

I guess it was cathartic. A lot of people aren’t around anymore. A lot of people committed suicide or overdosed on drugs and died. So from my group specifically, it was interesting to look at the photos with fresh eyes and over a decade of space. There were a lot of sentimental moments and I realized what a strong connection my group of friends had. I don’t think I would have been able to see those things at the time that I was taking these photos.

Can you tell me a bit about your background? What was growing up like for you? Your parents were religious right?

Yeah, my parents were pretty hardcore Roman Catholic. I went to church about three times a week until I was about 13. I was really involved too, so I was like an altar boy and could recite the Bible and knew the stories. From an early age I was always interested in religious art. There were all of these depictions of good and evil and now that I think of it, a lot of nude bodies. I loved the symbolism. That’s what I was into as a kid.

You had an older brother who lived in New York?

Yeah, he lived in the city and I would be dropped off at his and his boyfriend’s apartment. They were wild and gay and brilliant. Always singing and dancing. His boyfriend was a Barbra Streisand impersonator, and he got paid to do that. So it was fun; they always had costumes. His boyfriend would be acting stuff out from “Funny Girl." And my brother was really into Judy Garland. He just loved her so much. He’d always dress up like the Wicked Witch of the West for me. He’d put on this fake rubber nose and the green makeup. I guess it’s called being a Lion Queen, if you’re a gay guy and you know all of the Broadway numbers and movies. So he was the Lion Queen. He knew all of the lines and he’d act it out because he knew how much I loved it. It was fun to just hang with them and their friends who were other gay men. It was fun to go to New York and be raised in that environment.

When did you start going out to visit him?

As far back as I can remember. It was probably from when I was five years old until 13 maybe. My brother moved back in with us when I turned 13.

It seems almost surprising that your parents would drop you off there at such a young age.

Well they weren’t Catholic in that they would kick someone out of the house for being gay. They were okay with my brother. They followed the motto, “Treat thy neighbor as you’d treat thyself.” And I can’t remember, but maybe they encouraged him to go to confession or something like that? (Laughs) But my family is so close. There are eight of us. There’s an 11-year difference between me and my youngest brother -- so I was everybody’s baby. The brother I was visiting in the city was 17 years older than me. It was almost as if I could have been his son. I was just passed around between all of these people who just gave me so much attention as a young kid.

And you finally moved to New York yourself for art school.

It was my ticket out. There were these people who weren’t operating on the same wavelength as me. And I knew there was a good group of people in the city that were likeminded to me at art school. So I worked really hard in high school to develop my portfolio so I could get a scholarship at Cooper or Pratt or SVA.

There weren’t any artistic people around growing up?

My art teacher. We would hang out; she was my good friend. She’d talk to the principal and get me out of classes. She’d say like, “Ryan’s going to go to art school, so forgive his grades in this class. Let him spend more time in the art room.” She had breast cancer at the time. So, she was going through a crisis. And I was going through a crisis with my brother, because he was dying of AIDS at the time. So we really bonded. We would go into the city and hang together. She was just my friend. She knew exactly what I needed to do. She really guided me.

What type of artwork were you making when you were in high school?

I was really good at jewelry making -- making beads and crazy designs. But what I cashed in on, what I was known for in my town, was for making fake turquoise really well out of Fimo Clay. I would sell all these fake turquoise necklaces and rings at this shop at such a cheap price and all of the older women would buy it because it looked so real. Turquoise is pretty expensive. I was also really into sculpture and I really love Henry Moore. So I’d do a lot of carving of moonstone to make it look like Henry Moore and Isamu Noguchi sculptures. Then, of course, I painted a lot. Like I once made a painting of a guy with a computer head. It was pre-Internet. It was like, “The world is turning and people are going to have computer heads eventually!” Which is pretty much reality right now with everyone and their iPhones. And it was made in the Chuck Close style. You know how he paints like each little box and then you step out and it looks very realistic? That was my style and I did a lot of stuff like that. (Laughs)

You were pretty into skateboarding too right?

Yeah, I had this little Japanese silk-screening machine and I would make my own silkscreens at home. You’d just photocopy something and you’d put the photocopy on the machine and you’d press it down and it would expose it. And you could silkscreen whatever you made, anywhere. So I did a lot of skateboard decks because I would skateboard every day in high school. I would make a lot of designs and logos for my friends’ decks. Like cool punk collage designs.

Did Parsons and the city live up to its expectations when you finally moved? Or did you have to find your place?

No, I have always felt like this city was designed for me. When I moved here, it was the best day of my life. And there were no blogs or social media at the time. I found my crowd pretty quickly. At art school, I was with likeminded people. They were outsiders and gay people and of different economic backgrounds and races. It was so diverse and exactly what I was looking for.

When did you start taking photos?

Around the end of ’98. At that point, I’d gotten a boyfriend. I started photographing him a lot and then my group of friends, outside of art school. People I had close relationships with or met: skaters, graffiti writers, gay people. I was recreating a family. I come from this big family, but it’s like I got the opportunity to create this new one that I just love so much. I started photographing them on a daily basis.

You would do some dangerous stuff to get some of those photos. And getting images of some of the graffiti writers who didn’t want to be known must have been tricky.

Graffiti writers had so much paranoia because of the Graffiti Squad: the commission put together to stop graffiti in New York City. I was photographing all of the IRAK graffiti crew, which were at the top of the vandal squad’s hit list. Those guys were paranoid about their faces being seen in the photos with their tags on the wall. I was always shooting them while they were writing graffiti, but I could never show their face and their tag. I think just surrounding myself with graffiti writers, there was a healthy paranoia for them. Nothing ever happened. What really interests me about graffiti is the obsessive compulsive nature of it. I’m a magnet to people who are compulsive and obsessive. I think that’s how I found a lot of my friends. Just that personality of someone who is like, “Don’t look at me, don’t look at me, okay look at me.” I also love the risk that graffiti writers take too. A lot of the photos in my show are of people hanging off of the sides of buildings with a rope around their wastes, you know? That’s why I really loved Dash. Because when I met him, he was such an adventurer. He’d go out every single night. When I met him, I was so into that -- going into subway tunnels, on roofs, out onto the Brooklyn or Manhattan Bridge. All of this crazy, insane, dangerous stuff was just so fun. The experience is super exhilarating.

Back to art school for a second, what is it about it that you think is so beneficial?

I think it’s the structure. I think it’s a little of everything. There was this one teacher who really changed my life who taught this class my fifth year of school called “Nudity, Sexuality and Beauty in Photography.” It was a game changer for me. I really needed that structure. I think if I hadn’t gotten that, I don’t think I would have been able to survive in New York. I would have had to get a job and I wouldn’t have had enough time to make my art and develop as an artist. School really accelerated my evolution and showed me what I didn’t like, you know? It brought me closer to the things that I did like and what I was good at. And for school, I had to be up at 8am. If I wasn’t in school I would have easily slept until like 1pm every day. My first year at school I went for painting and then my second year I did poetry and then my third and fourth year I switched to graphic design, and then my fifth year, I switched to photography. I think if I didn’t have a peer group or the facilities that the school provided, I wouldn’t have been able to make those leaps. Or really figure out what I was interested in. And I was one of those kids who really used the school and took all of the classes to try everything out. I was all over the place and after five years, I didn’t even graduate.

Oh really?

It wasn’t until two years ago, they called me to be the commencement speaker. I said, “Yeah, I’ll do it. But I just want to let you guys know that I never graduated from Parsons.” And they were like, “Oh my god. We’ll give you your honorary degree!” So I mean, I was there for five years and I did do a lot of stuff, and it was awesome. I’m really pro school. I know a lot of people aren’t. I have a lot of people that work for me that ask me that question all of the time. I try to sit them down and talk to them and try to figure out what type of person they are; do they need structure or are they someone who seems to self-discipline? But I think it’s a good thing. And it also bought me five years of not having to have a job. So fucking awesome. I mean, when in your life do you ever get that opportunity -- to really focus on your passion without having to work? I got a good scholarship there and that helped.

•