With her latest EP, Negotiations, Kilo Kish confronts the emotional toll of digital culture and reclaims space for nuance, rest, and plurality in response to an industry built on speed.

interview by Summer Bowie

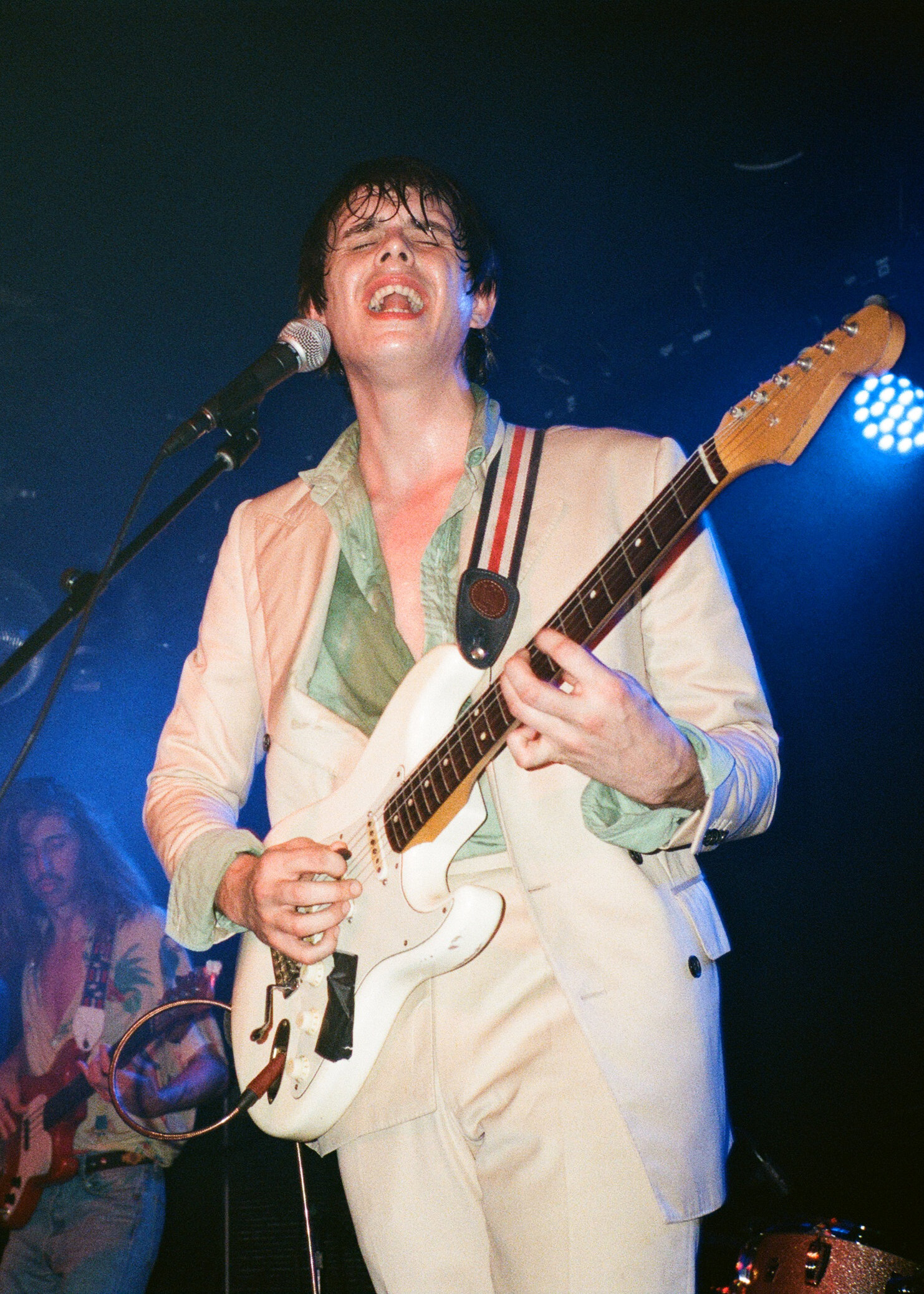

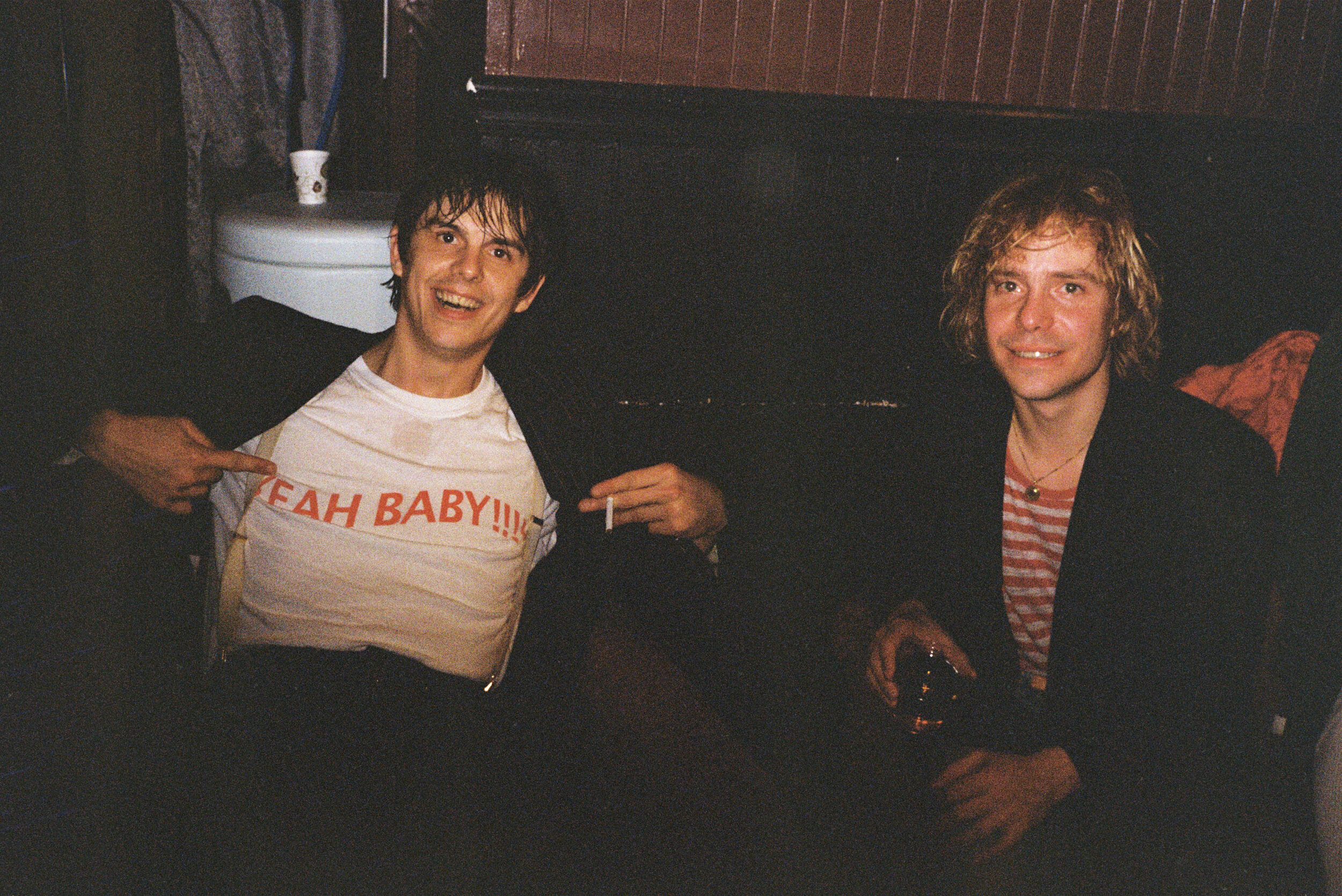

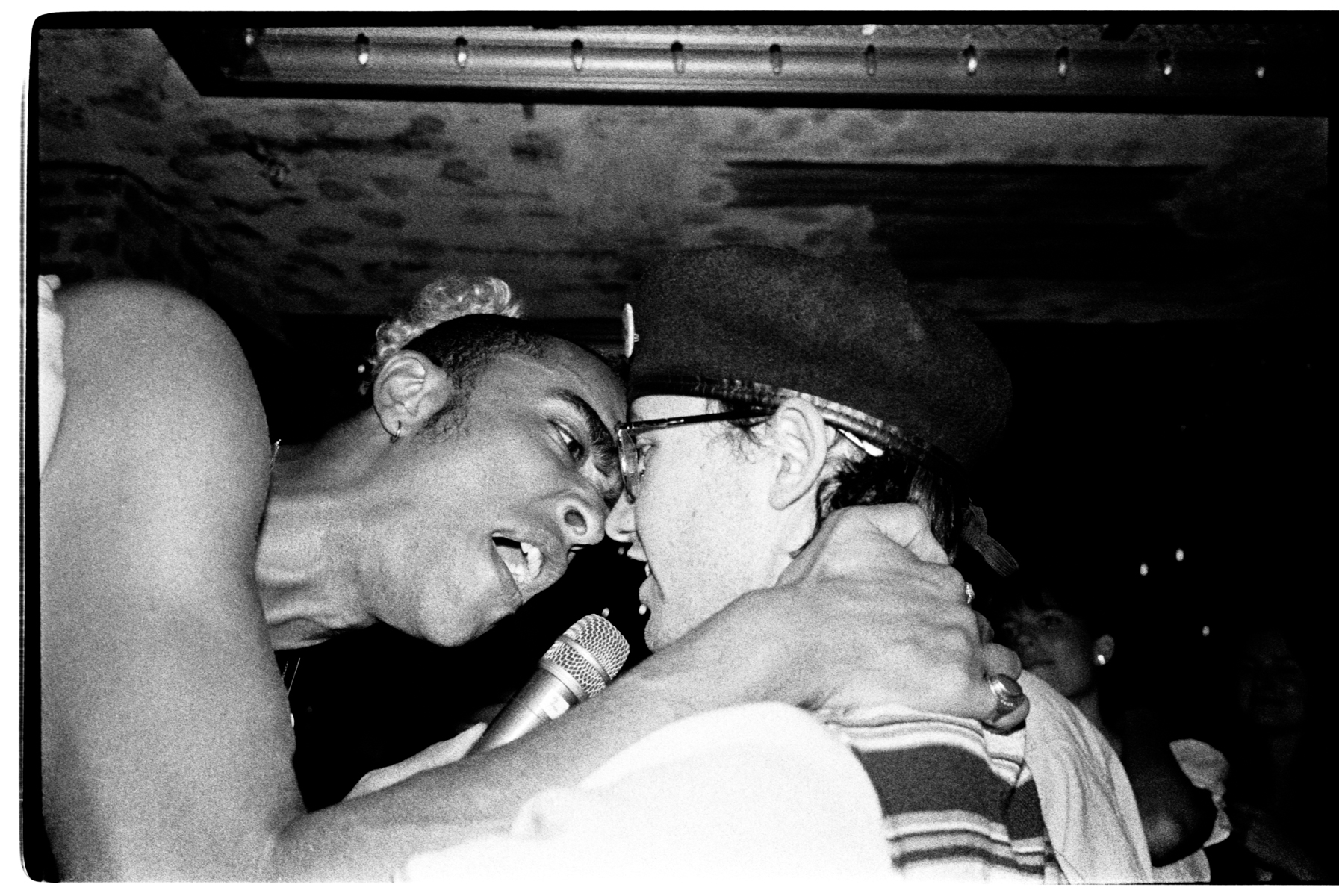

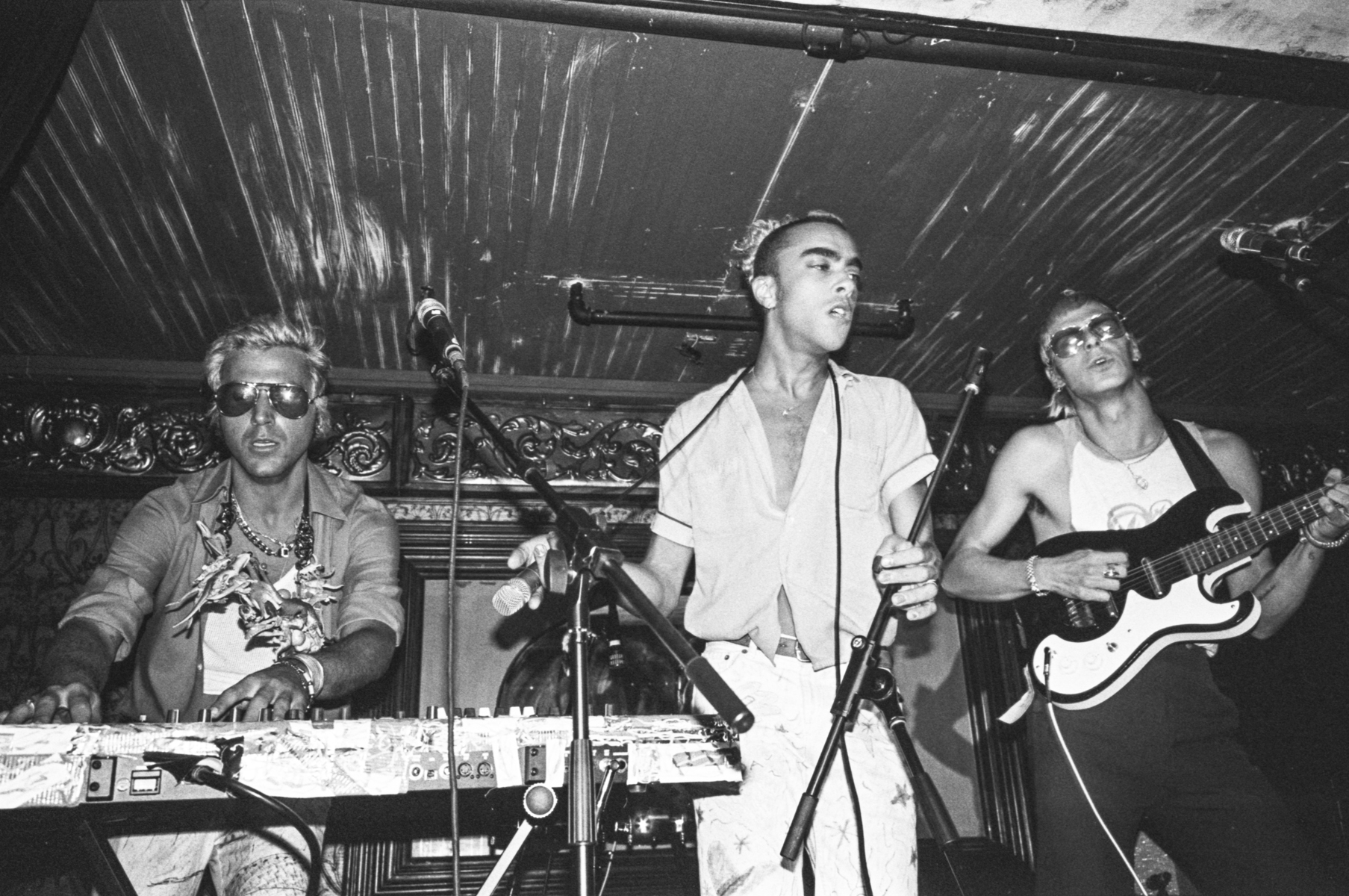

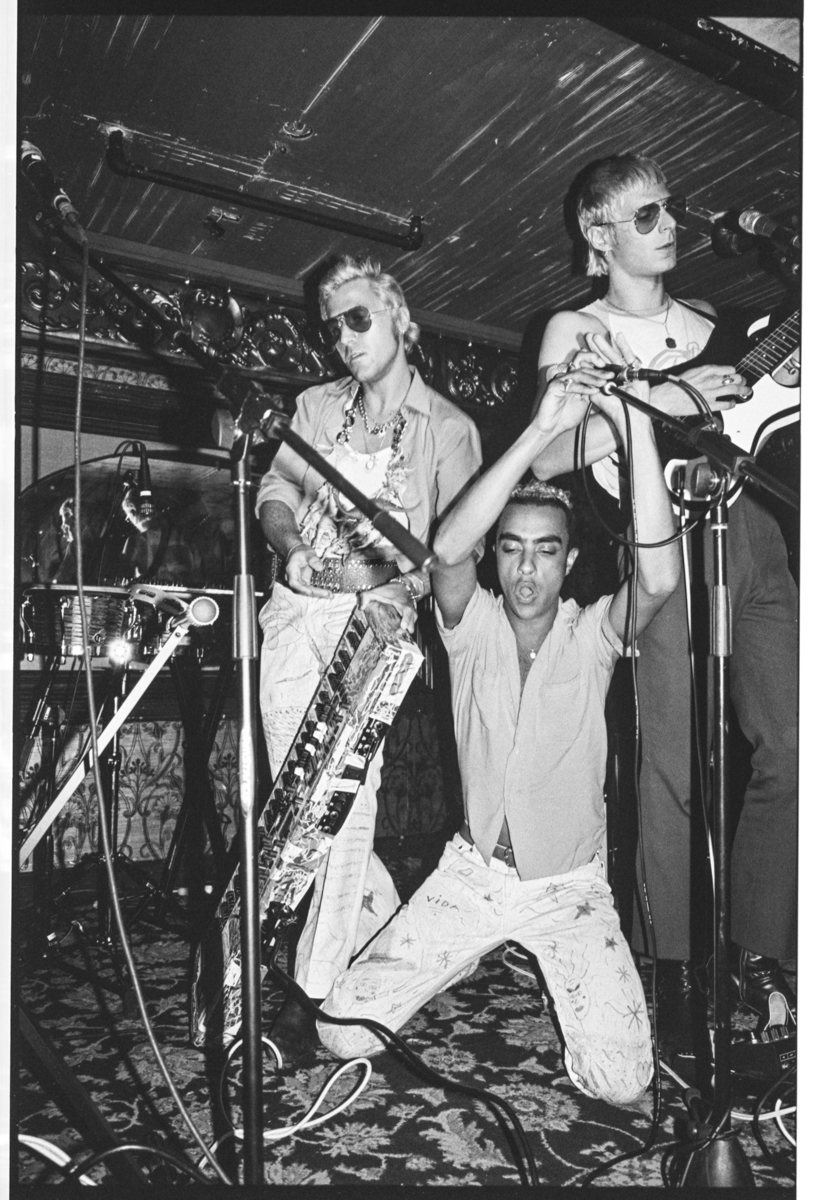

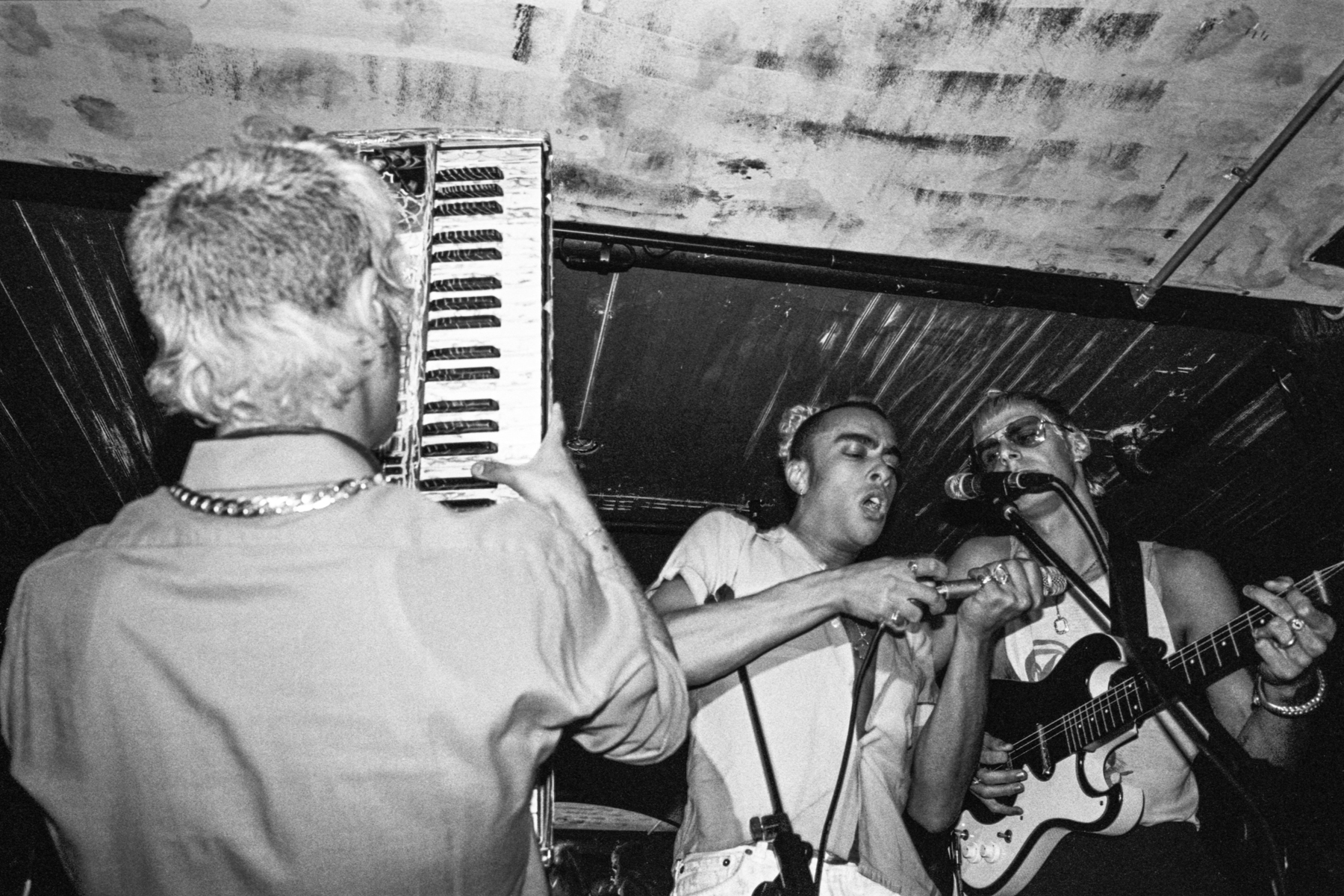

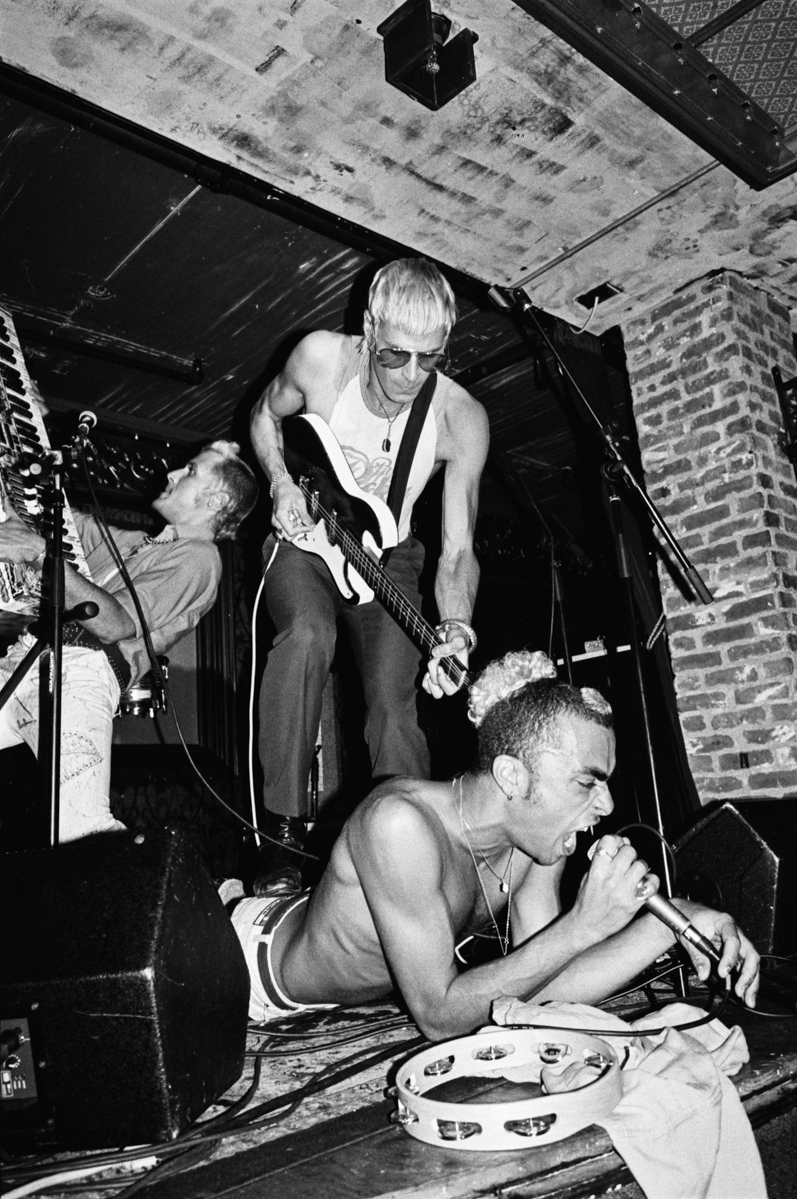

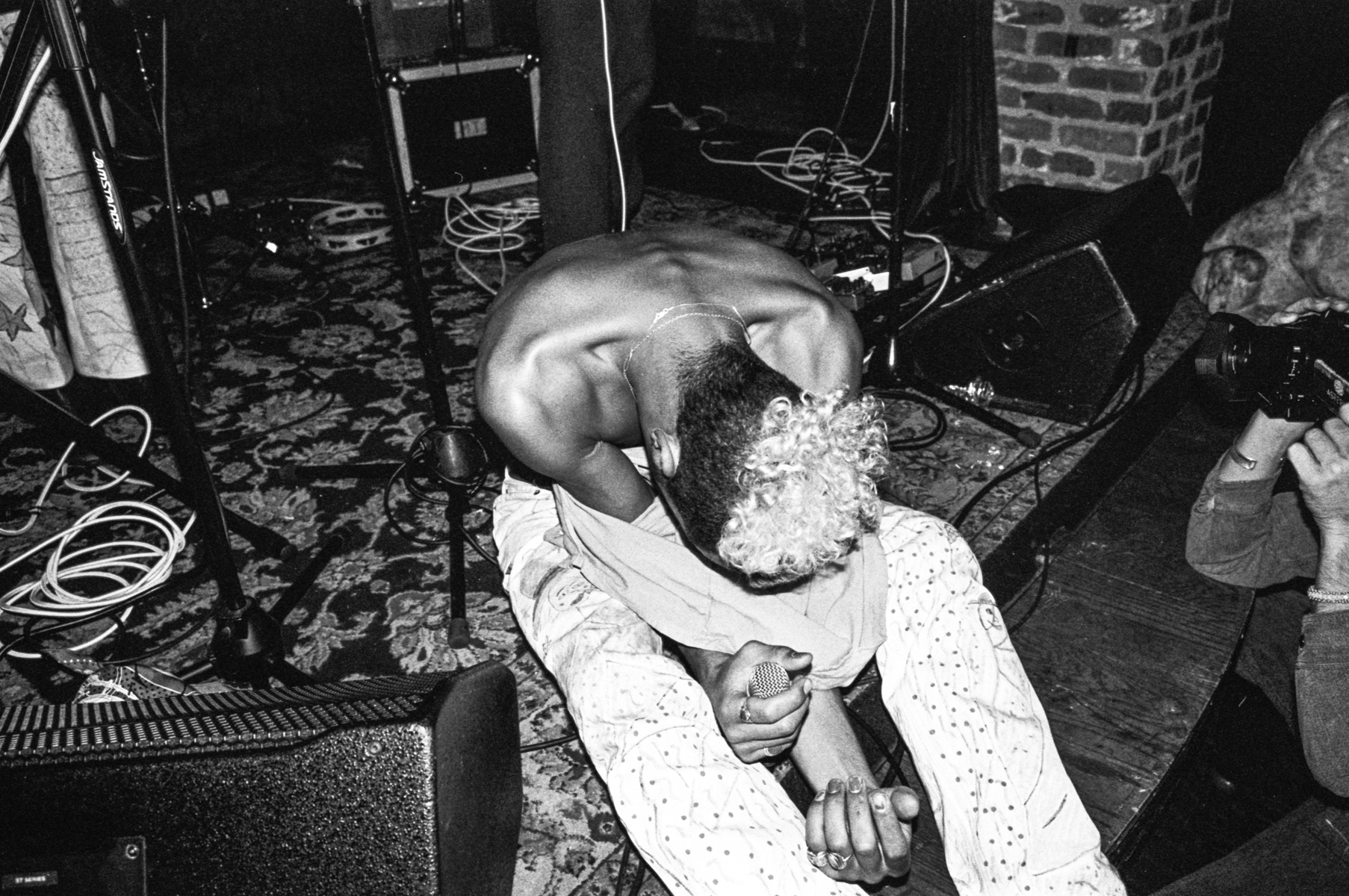

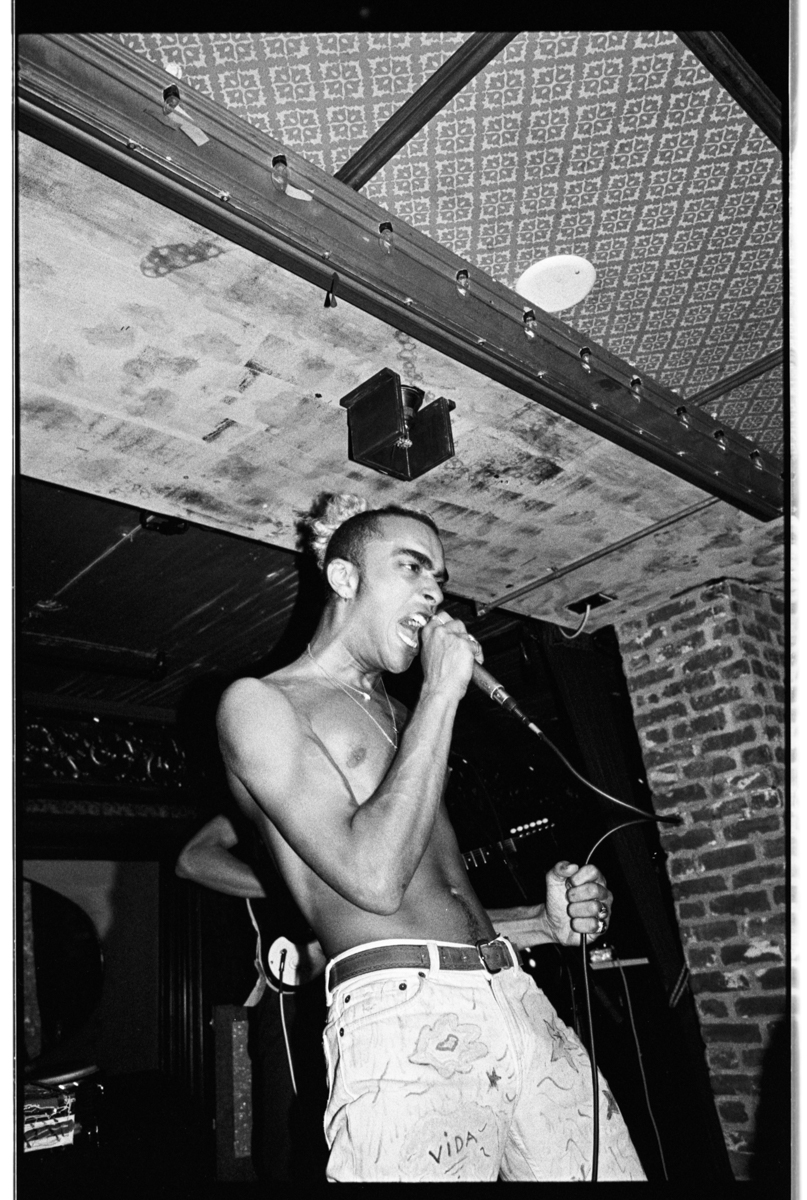

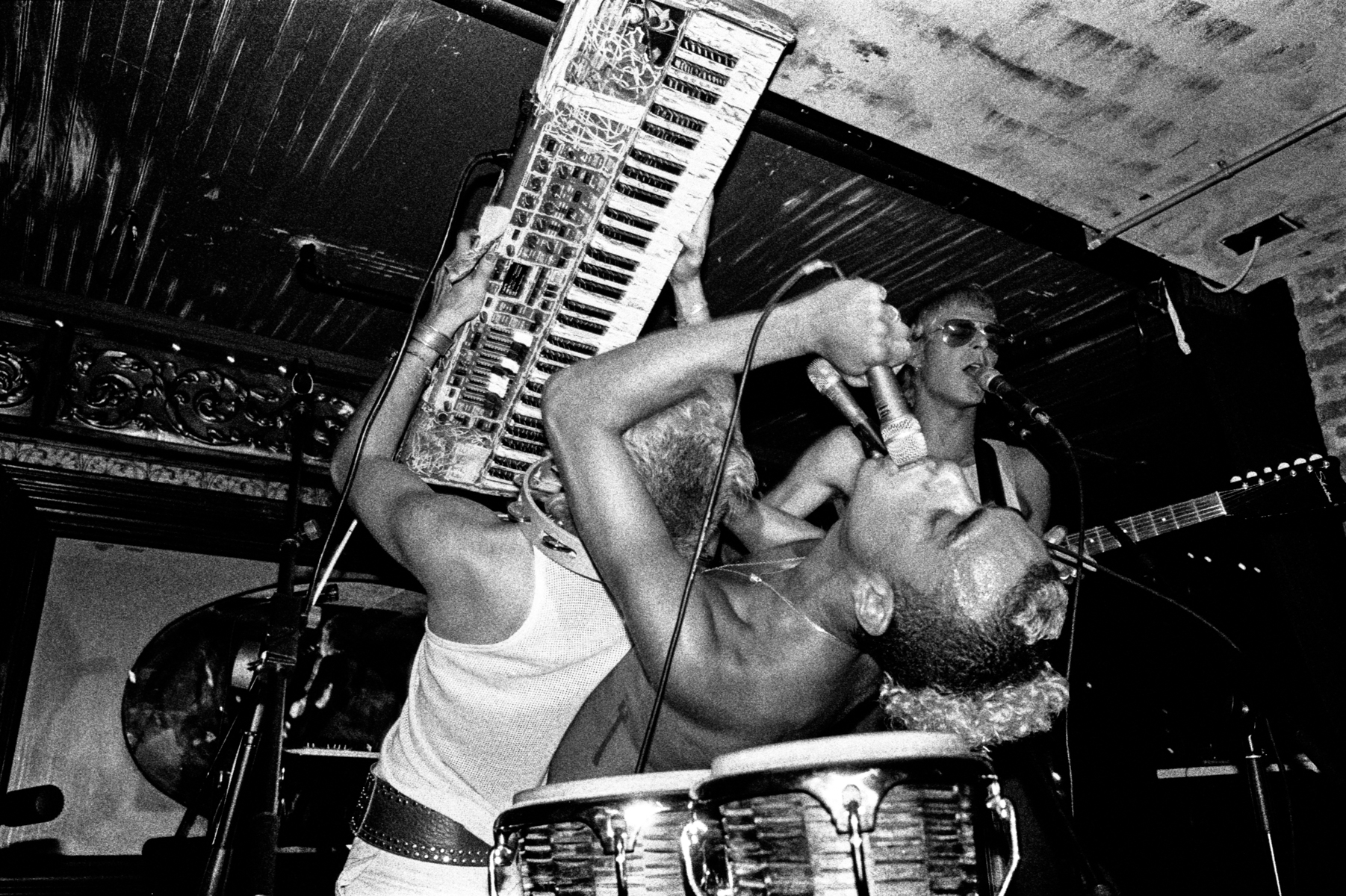

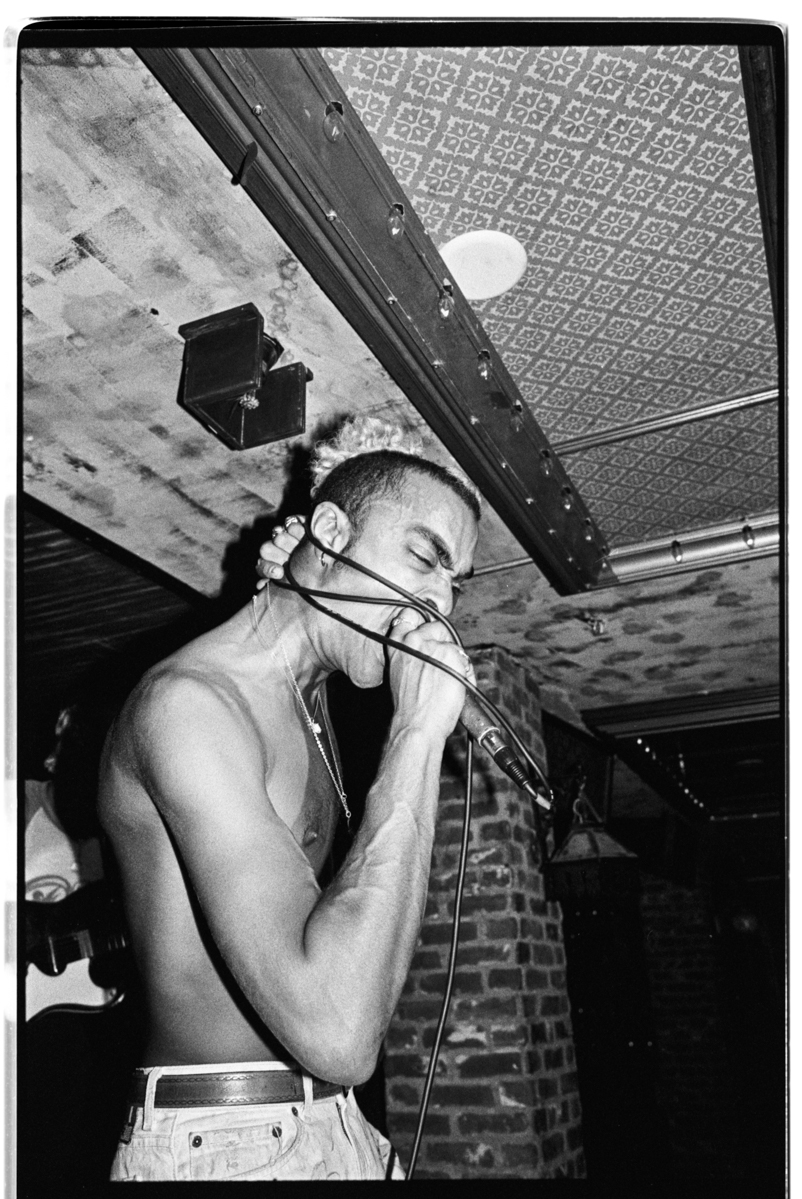

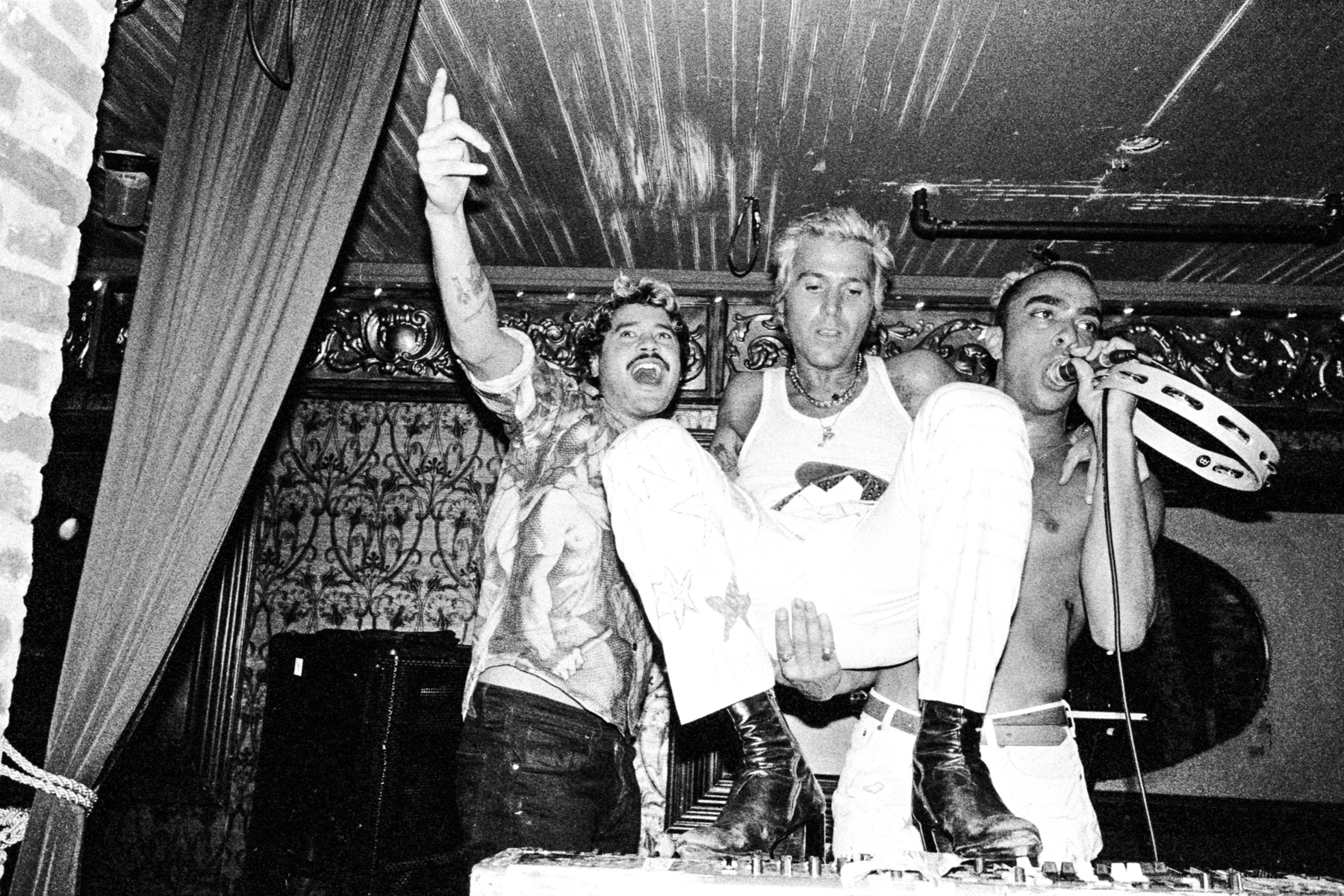

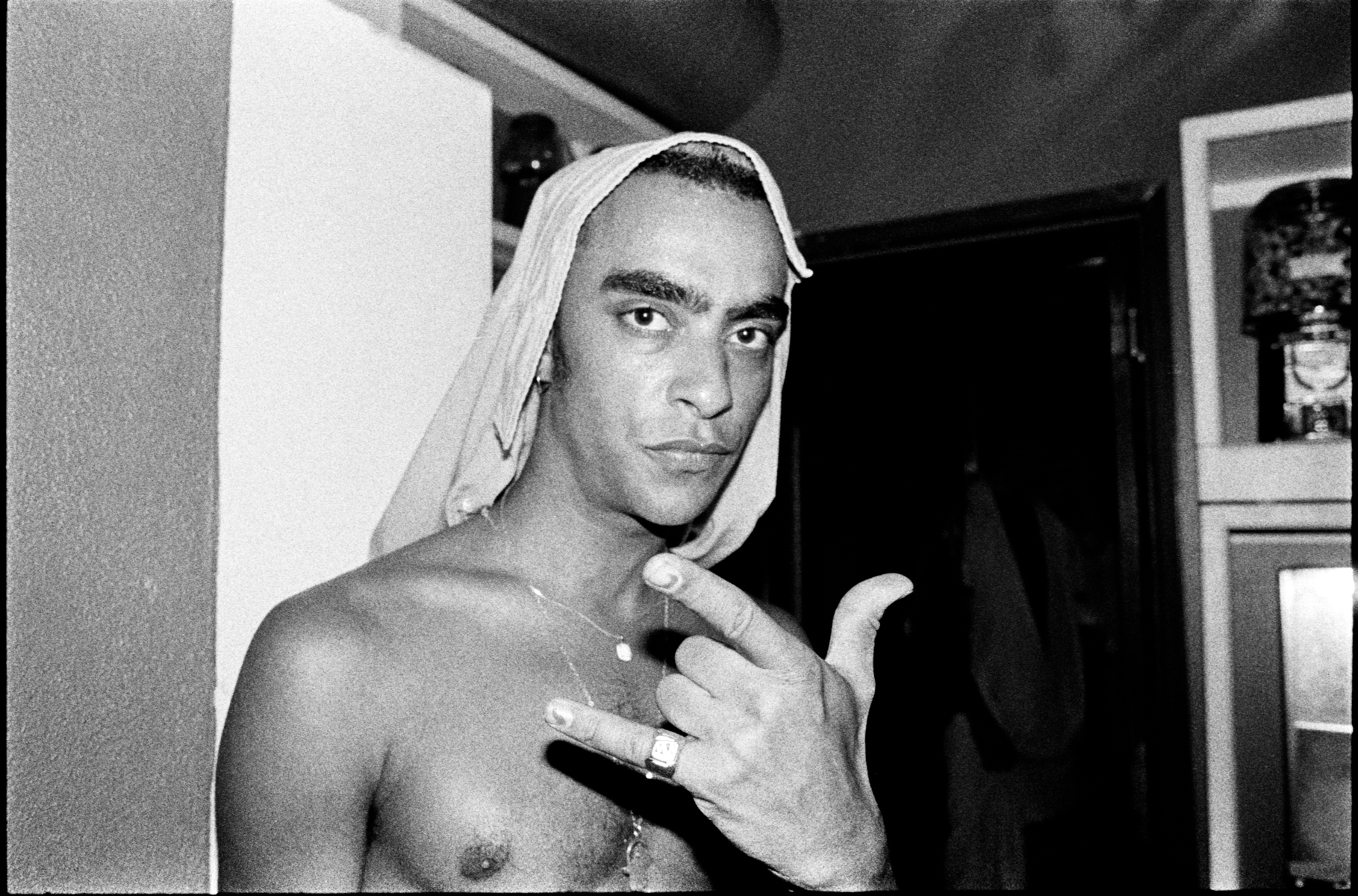

portraits by Dana Boulos

Despite the ever-shifting expectations of digital culture, American artist of sound and screen Kilo Kish continues to carve out a space entirely her own—one that defies genre, challenges structure, and insists on emotional honesty. With her latest EP Negotiations, Kish turns her gaze inward and outward, interrogating the increasingly blurred boundaries between human and machine, performance and authenticity, burnout and resilience. Through textured soundscapes, fragmented narratives, and a visual aesthetic that’s both nostalgic and hypothetical, she invites us into a world where self-care is a form of resistance.

How do we nourish the spirit while navigating systems that rarely pause for breath? Kish speaks candidly about the emotional labor behind her output, the philosophies that anchor her worldview, and the freedom she’s found in embracing multiplicity—of identity, of media, and of meaning. What emerges is a portrait of an artist in motion: reflective, adaptive, and uncompromising in her pursuit of truth through art.

SUMMER BOWIE: Your new EP, Negotiations, is all about the slippery contemporary landscape of rapidly evolving technology, emotional instability and the struggle to escape our algorithmic silos. Are there any specific life experiences that inspired its conception?

KILO KISH: This EP is focused more on the music industry and the social expectations of artists in 2025 and how they can lead to burnout without proper self-care and protections. With this one, I thought a lot about these creative systems imposed and the internal creative systems in the body, heart, mind, and spirit that require the same nourishment to perform. Just wondering to myself, where is the nourishment going to come from in the future? How do we build ourselves strong to survive and thrive creatively? In thinking of stamina and productivity, what first came to mind was robots, autonomous factories and storefronts, and systems that don’t require rest. So, the visual and creative world was built from that.

BOWIE: Your visuals—album covers, fashion, and videos—often evoke a futuristic yet nostalgic feel. How do you develop the visual language for each project, and what role does mood or time period play in your aesthetic decisions?

KISH: I didn’t want the impression to be so futuristic or on the nose, I always love bringing in the conversation about technology or the present in settings that don’t necessarily evoke it, so we chose this ’90s office building. I build the world first and then the music, so I’m always clear that the mood of the music and the visual world will be harmonious. When making films that go with the music, I’m already really clear on the characters and ideas that I want to employ, so then it’s just finding collaborators and explaining the world to them.

BOWIE: What does a typical creative cycle look like for you—from idea germination to completion? Is your process more intuitive and chaotic, or do you map things out structurally from the start?

KISH: It’s very intuitive. My approach to storytelling is purely an internal dialogue and a spiritual practice of just listening. I only make work when I know I am supposed to make it and that comes from hearing from god or my own questions about my path. The first step is just listening—I’m always living and listening to what is next and where I should go. Journaling helps. But I’m always working on multiple projects, so while I am doing one I may get a clue for something else and write it down. I’m always gathering references, so when things pop up that may work for the new project I build out digital spaces for that. As I finish one project, I eventually have all the clues I need to begin the next one. That usually consists of rough ideas, questions, visual references, art direction, rough treatments—but a sense of the world is built internally, and I have a direction. Once I know the world, I start the production process of actually making. So I’m always making at least five to ten projects but in various stages of completion. But a lot of it is just listening, getting quiet enough to have enough alone time or internal practice to feel what wants to come forth next. I’m often wrong about order or timing, but it always works itself out.

BOWIE: You’ve seamlessly blended music, visual art, and fashion in your career. Do you see these disciplines as separate expressions, or are they different languages telling the same story? How do you navigate where one ends and the other begins?

KISH: I think it depends on the project. They work in tandem to create a more expressive world or story, to me it’s all intuitive and they’re all important to sharing ideas. It all feels very natural to me to play in these different spaces, in expressing this nature to others over the years there were always outside requests to slim down, or streamline who you are, now it’s a bit more accepted, which is great. But before, so much of my time was spent trying to explain how or where things began and ended, which was the “focus,” and I just confused myself ultimately. I saw a coach who helped me to detangle it and I see these extensions now as islands, all of them exist as parts of me and my way of telling stories, and there are bridges between them at times, and these configurations can change, but they are all me, and all existing in me always. There are islands I haven’t discovered yet. I’ve grown more comfortable holding this version of myself as truth. I really like this song by Empress Of called “What Type of Girl Am I?” It’s a question I’ve asked myself tons of times too.

BOWIE: In addition to your 2021 video and track “American Gurl,” you also curated an exhibition of short films of the same name with co-curator Zehra Ahmed, first at Hauser + Wirth and most recently at MOCA in Los Angeles. Can you talk about the genesis of that project?

KISH: Zehra had featured some of my video work in her womxn in windows shows previously. We first worked together more closely when I did the Midnight Moment with Times Square Arts. The concepts from American Gurl felt so expansive and like there was a lot more to explore so Zehra proposed creating a film exhibition together, kind of blending what we both already do, and so we started working on bringing that to MOCA some years ago. The Hauser show and the Gantt Center show were pleasant surprises in between that initial idea. We have an upcoming guest curation at the Academy Museum this summer as well! Zehra and I gel well creatively, and we’ve found a beautiful niche that’s been really rewarding to bring to the public.

BOWIE: In works like American Gurl, there’s a conversation around digital identity and the hyperreality of modern life. What’s your perspective on how technology affects our sense of self—and how do you channel that in your art?

KISH: There’s this constant questioning of the self against other things, and these other entities: people, systems, spaces, etc, are constantly in our view and held against our bodies. At this point, detachment from that source of information, inspiration, or entertainment is difficult for lots of us. Although, when explored with purpose it can be very rewarding, I love scrolling through pages and pages of reference or researching things that pop into my mind. But the thing is, you never really know what you will come across or how it might affect you, so I try to give myself breaks or grace around processing time online. I think I aim for freedom and this attitude of being above it all, but in our industry, perception is important and it exists whether you choose to commune with it or not.

BOWIE: Your music often challenges traditional pop structures, mixing spoken word, noise, and ambient textures. What draws you to sonic experimentation, and how do you balance abstraction with accessibility?

KISH: I guess I just want everything, all the time. It’s part of the “problem” of my work and what makes it unique. I try to balance things that seem to be in opposition or find the threads that connect them. I think boredom with who I’ve been before is a huge motivator for me, I like evolution and watching ideas change over time. But really, I’ve always just identified with otherness, like, “we could do that, but what about this, we don’t know what happens if we do this.” I just love being an explorer, of our blip in time, of the inside, and the outside.

BOWIE: Much of your work explores identity, consumerism, and modern alienation—often with philosophical or existential undertones. Are there particular thinkers, books, or theories that have significantly shaped your worldview and creative output?

KISH: I’ve always been a very spiritual and purpose-driven person, so years and years of meditating on god have informed this approach to life that says, we all have a purpose and we’re meant to explore, give, and live as humble and as noble as possible, sharing the truth and gifts of our spirit with the world, seeing the body as a channel for ideas to come forth. Like in another life, I could have definitely been a nun, I like the idea of being in service to all but yourself. But too much of this, this martyrdom of the artist part that’s always in the background, was responsible for much of the burnout I touch on in Negotiations. At the same time, I am a product of my environment and my world that says, “Grab up as much as you can for yourself and become the biggest version of yourself you can be.” I’ve read so many self-help, productivity, meditation, stoicism, healthy living, spiritual texts, etc. I have this fixation on what it means to live a good life. I think learning to balance these elements and giving grace for what is left unknown is what I’ve been focused on recently. I constantly return to the Denial of Death (1973) by Ernest Becker and Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911) by [Wassily] Kandinsky. But much of my practice is intuitive and listening to myself and what comes forth.

BOWIE: Many of your lyrics feel like internal monologues, offering listeners a peek into your thought process. How do you decide what emotional truths to share, and do you ever feel the need to protect parts of yourself from the wider public?

KISH: I do, but not so much in the art itself. Music to me doesn’t always have to be about the songwriter, so you can hide a little in that space if absolutely necessary. There is this reality and fiction existing at the same time and we expect that too. I think I definitely protect myself elsewhere, in my personal life, or even meeting people in public, even if I just performed for tons of people, I can be really shy afterwards. Also online, I’d rather just present the work than present myself to camera daily.

BOWIE: As someone who often moves outside of genre norms and mainstream expectations, how do you maintain your creative independence in an industry that can reward predictability? Have there been moments where you had to fight to stay true to your vision?

KISH: To me nothing really feels like a fight. It either just has to happen or not, and you’re on board, or you’re not, and I’m just following that flow in the dark a lot of the time. It can be stressful at times, though, waiting for things to unfold completely, but I know the decisions I need to make to serve the purpose of the project. I think there are many paths to winning, some just require carving out. Everything I have set out to do I have done bit by bit, and if I haven’t, I’m not done yet. It can be daunting and demoralizing for sure, because repeating yourself or your angle time and time again begins to change the meaning behind the words. There is this interview with Venus and Serena Willams’ dad where an interviewer keeps questioning them about a statement one of them made in confidence, eventually their dad stops the reporter, reminding him that the more times you question someone on something they hold true, they begin to lose confidence around that idea. Believe them the first time. I think this business can do that, wear you down, or make you feel small for wanting a different option or another path, or confuse your value or worth with that of numbers. Imposter syndrome is real and definitely plays a role, but I’ve learned to accept that my perfectionism is ingrained even if it’s unattainable. It try to give myself grace in that when I remember that everyone is grading by different measures.

BOWIE: Looking ahead, what kind of artistic legacy do you want to leave behind? Are there unexplored mediums or themes you're still yearning to dive into that might surprise your current audience?

KISH: I just want to continue to build worlds that people can live and explore themselves in—sonic, video, written, visual, performance. Creatively, I just want a lush, rich, expansive life that pulls from all elements. I would like to be prolific in that sense, not overthinking things, just exploring and doing. I’d like to direct a bit more, short narrative, or maybe make a play or opera. I would love to make more performances that involve music and dance. This year, I’ve done more creative work for others and that’s been rewarding. I designed a book called City of Angels for my good friend Jasmine Benjamin, about LA style. I want to play with nature, make physical spaces, grow food, and build landscapes. There’s still so much left to do.