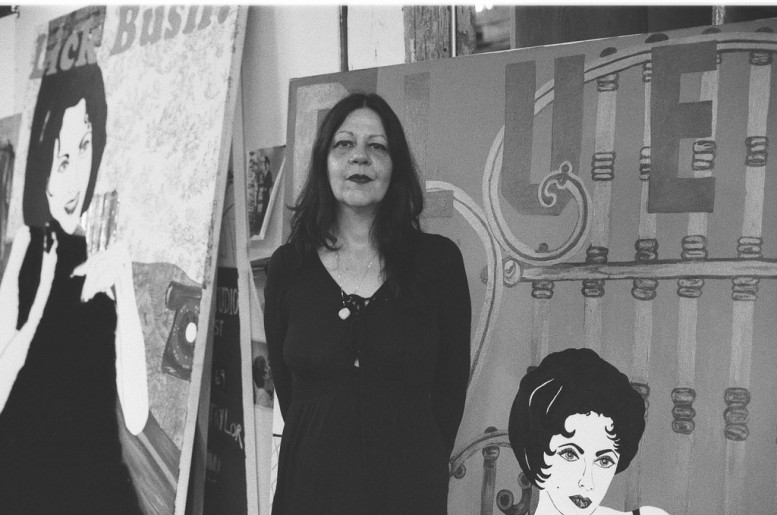

Anahita Razmi is one of those artists that are tough to define, but all the same make shock waves that force us to take a deeper look inside ourselves. Ramzi, a video and performance artist based in Stuttgart, makes work that deals with issues concerning identity and gender by employing objects with a national and cultural significance; sometimes borrowing and citing the work of other high-profile artists. Working within the tradition of appropriation and re-enactment, Razmi detaches cultural symbols from their established meanings by employing them in unexpected situations and contexts. Her works, like the tongue-in-cheek Burquini which was designed for the swimming activities of Muslim women and the more serious Roof Piece Tehran, where she had 12 dancers dancing on the rooftops of different building in Tehran in a county where dance is illegal and artistic performance is forbidden. Ramzi, whose father is Iranian – her mother German – has a special connection with Iran and it’s panoply of struggles. On view now at Carbon 12 Gallery in Dubai, Ramzi’s solo exhibition Automatic Assembly Action, which opened with a performance RE / CUT PIECE, a modfied appropriation of Yoko Ono’s 1964 performance Cut Piece, will be open until March 14. Pas Un Autre got a chance to ask Razmi a few question about her artistic practice, her current show at Carbon 12 and what she has planned for the future.

PAS UN AUTRE: When was the first time you realized you wanted to be an artist?

ANAHITA RAZMI: For me there was no decision of becoming an artist, it was more a progress within time. I studied media arts before continuing in fine arts, but never became passionate about just editing or designing stuff. For me being an artist means dealing with a lot of risk, but also with an incredibly multifaceted field of themes and references. I don't think one can become tired of it.

AUTRE: What does it mean to be a female artist in the 21st century?

RAZMI: I wouldn't choose to speak generally, but at least for me I feel and hope that categories like male - female at least for artists working conditions become more and more irrelevant these days. My work still often deals with these categories in a broader sense, but I am trying to question stereotypes and preassigned images, rather than determining them.

AUTRE: Can you name some other female artists who inspire you and why?

RAZMI: My work is often referencing other female artists work, - for example I recently quoted Tracey Emin and Cindy Sherman. Anyhow, I am quite amenable for inspiration, I never choose to sit in my studio and work from a blank sheet of paper.

AUTRE: What do you think is the biggest spiritual quagmire for people in todayʼs times?

RAZMI: Dependancy on questionable values and rules. That deserves a bigger discussion however.

AUTRE: Is art important in politics….how can art spark political discourse?

RAZMI: I don't think art should at all be considered as something with a function. Anyhow, I still feel that it can be an independent factor questioning political situations and conditions within a society by activating discussions, thoughts and possible reconsiderations.

AUTRE: Some of your work has dealt with the politics and restrictions imposed on people living in Iran….is religion a problem or is it how people use it?

RAZMI: A lot of my work is making reference to the current situation in Iran. Anyhow I am never choosing to explain about the country, - I am more making reconciliations between existing images that are shifting between the Middle East and the West.

AUTRE: Your work is extremely multifaceted and people seem to have a plethora of ways to describe it – how would you describe your work?

RAZMI: I am happy to hear that, as I don't like my work to be pigeonholed. I am using different kinds of media and am not sticking to one method of producing my work. Still I think, one can find repeating conceptual strategies within my practice: appropriation of existing works and images, certain themes (like contemporary Iran) that repeatedly are dealt with.

AUTRE: Can you talk about what we can expect at your upcoming show at Carbon 12?

RAZMI: The show is my first solo exhibition at Carbon12 Dubai, so I am quite excited. It is titled Automatic Assembly Actions and features two new video installations, one photoseries and a textile work. I also did a performance during the opening, which involved the audience.

AUTRE: Whatʼs next?

RAZMI: My show Swing State will open mid february at Kunstverein Hanover, which will be accompanied by a publication. From april on I will be in residency in Los Angeles for 6 months working on a new project - really looking forward to that.

Text by Oliver Maxwell Kupper. Anahita Razmi Automatic Assembly Actions will be on view at Carbon 12 Gallery until March 14, 2013, Warehouse D37, Alserkal Avenue, Street 8, Al Quoz 1