text by Chimera Mohammadi

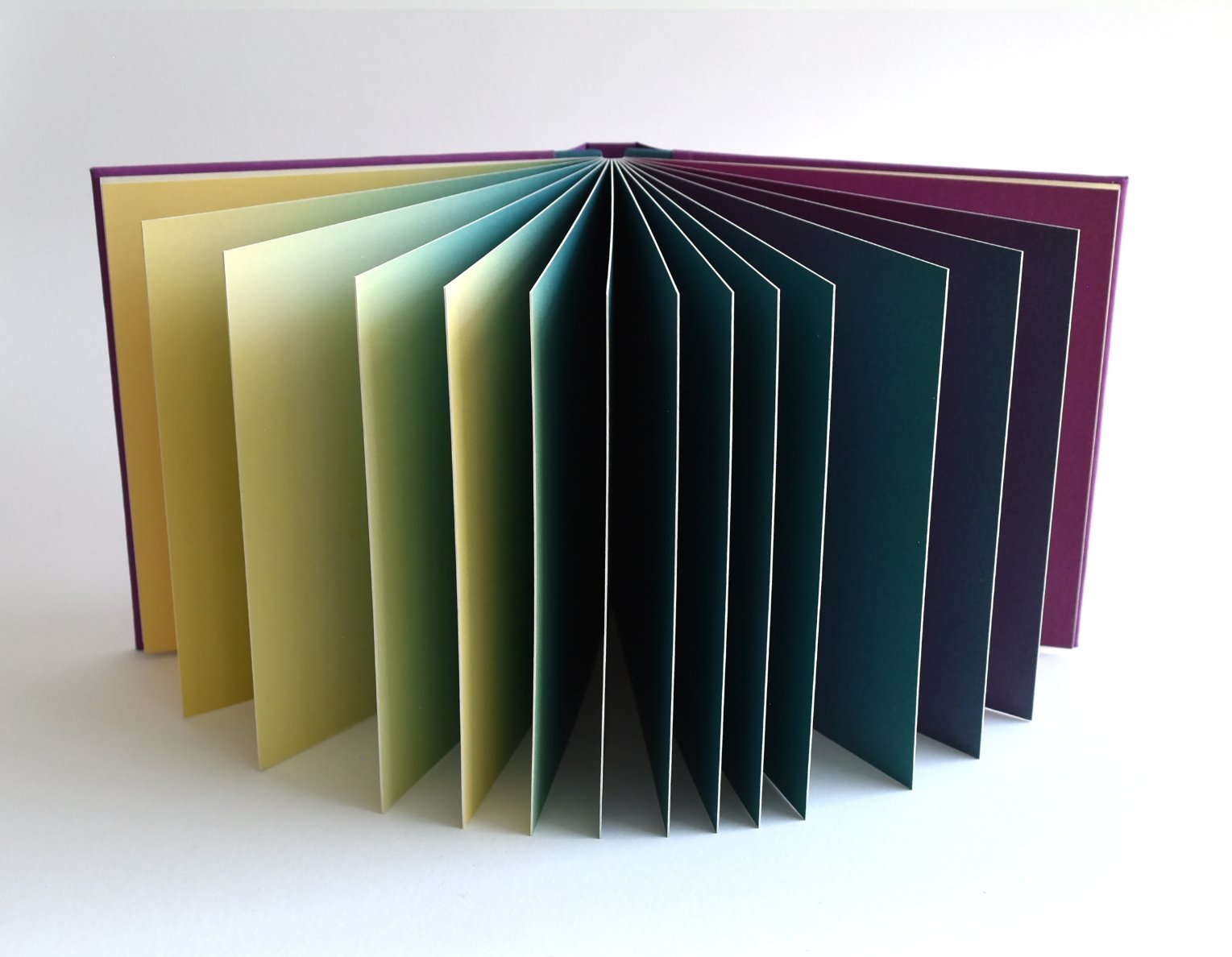

“I lingered in front of the bar and felt eyes search my face.” As the words flit across an uncanny array of printed eyes in Malic Amalya’s short film “Flyhole,” Amalya confines in language the current that unites the work in The Embodied Press: Queer Abstraction and the Artist’s book, a touring exhibition curated by Anthea Black which has just finished its Berkeley stop. The show consists of a glorious collection of Queer aesthetics that question whether they want to be seen and ultimately insist upon it, considering the tenuous relationship between Queerness and observation without compromising the Queer right to be seen. The space where Queerness and spectacle overlap has often held violence: The Embodied Press is a reclamation of that space, thrusting the historic traumas of the Queer community into the spotlight while soothing the resulting discomfort with self-owned Queer spectacle. Lyman Piersma’s delicate, heartrending recordings of life during the AIDS epidemic and Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo’s brutally raw love notes and protest poems imbue the space with a revolution-inspiring pathos. Kate Laster’s kaleidoscopic collages suspend themselves in space like bursts of visual jazz, and radiant books of wordless color gradients by Nicholas Shick embody the transcendent euphoria of gender transition. Married couple Miller and Shellabarger’s hazy fields of pastel erotica pepper the space like escape hatches, doors into a welcoming party, while their massive paper dolls cordon off corners for “Flyhole” and Nadine Baritueau’s “Au Revoir” to quietly question the paranoia of being seen and the appeal of disappearance.

The Embodied Press is on view through February 9th, 2024, at Kala Art Gallery at 2990 San Pablo Ave, Berkeley, CA 94702.