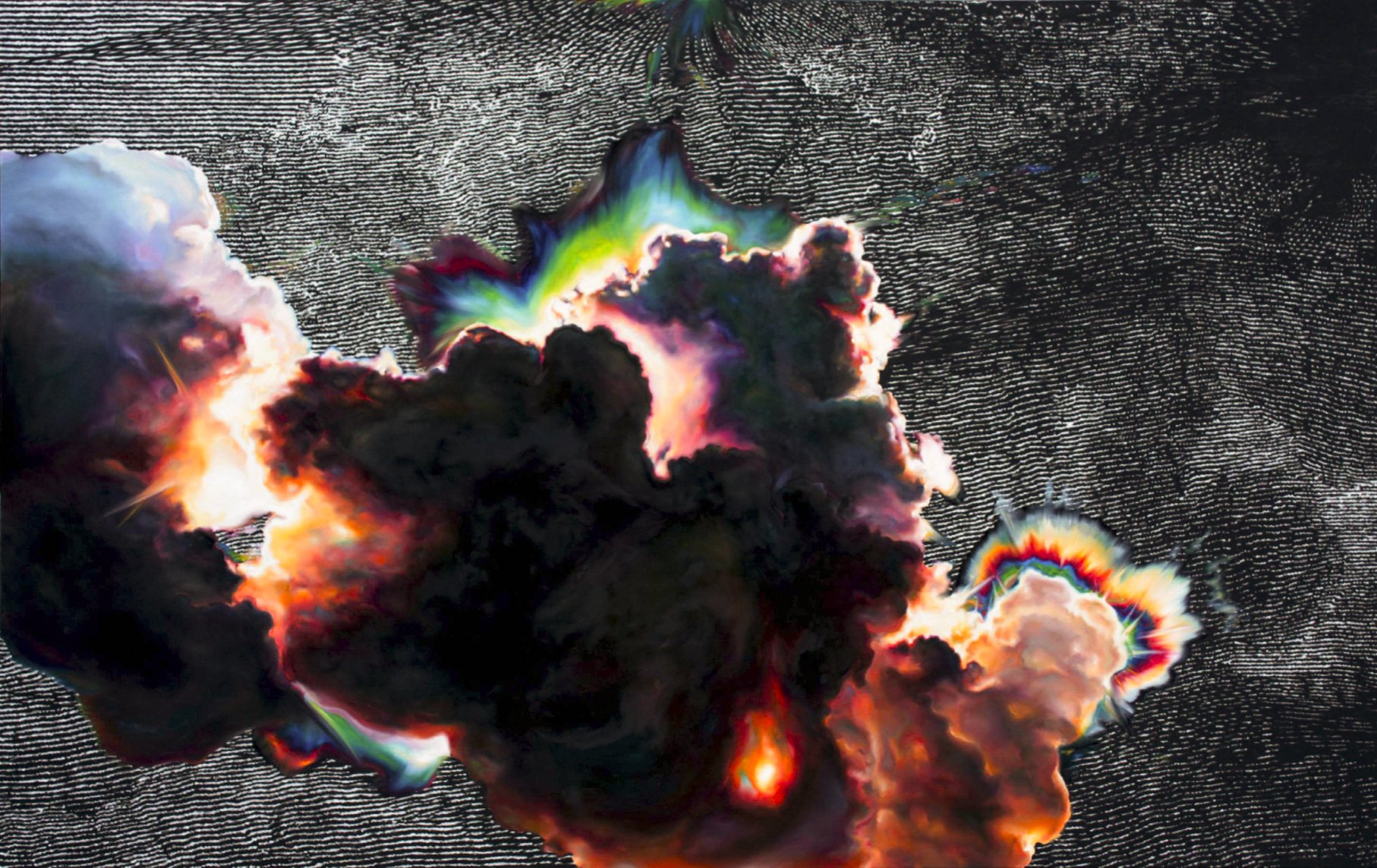

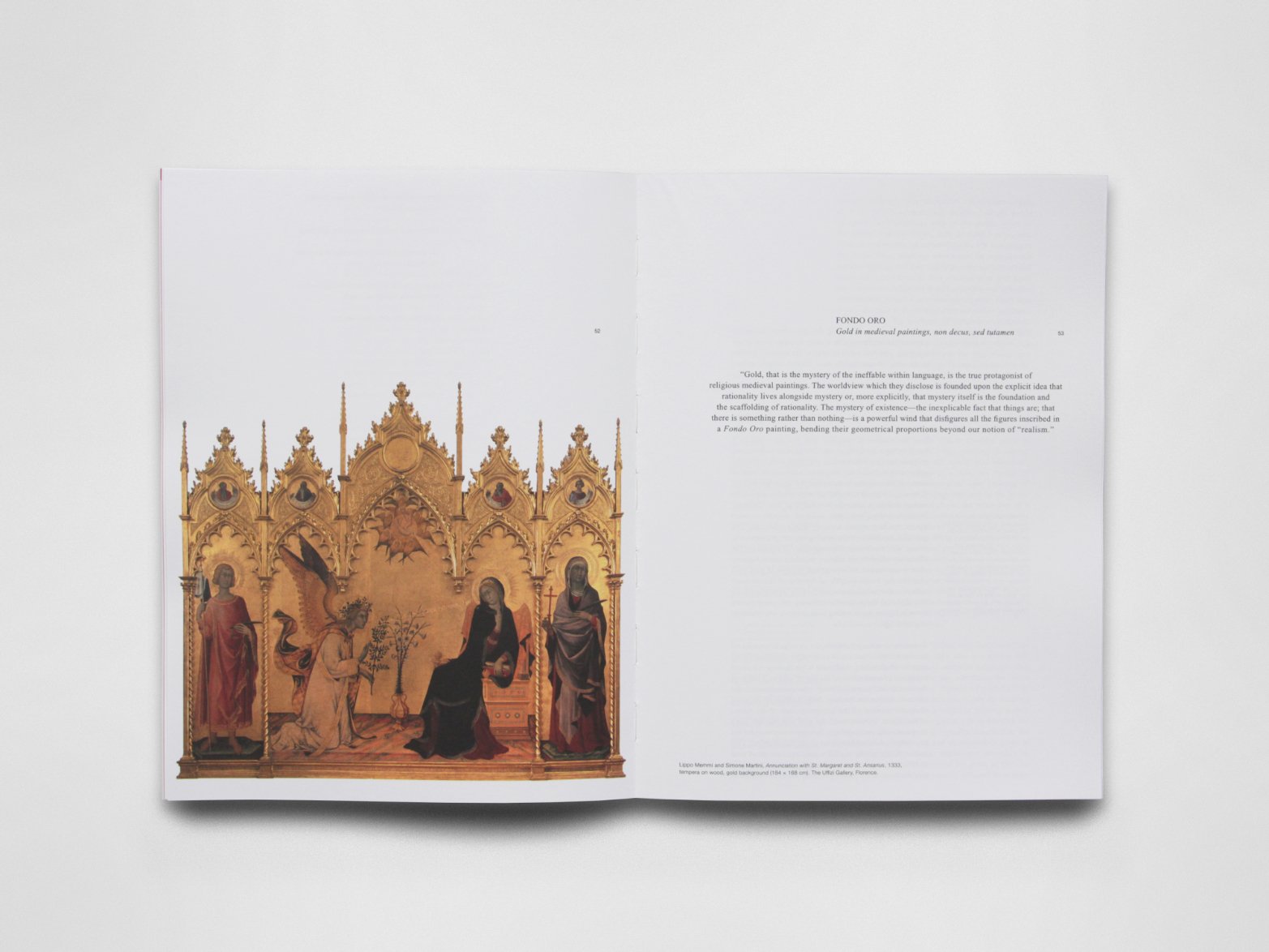

Installation view from Shirin Sabahi’s exhibition, The Moped Rider, 2022

Bryggens Museum. Courtesy the artist © VG Bild-Kunst, Bergen Assembly 2022 convened by Saâdane Afif and curated by Yasmine d´O. Photo: Nicolas Rösener

text by Lara Schoorl

The days after the opening weekend of Bergen Assembly, my (personal) quest for the Heptahedron continues. Revisiting my notes, the exhibition texts and issues of Side Magazine, searching for names, plays, the histories of artists, artworks, and possibly imaginary people, I am not quite lost but certainly uprooted in the spiraling narrative that Saâdane Afif inspired across seven exhibition sites in Bergen, Norway.

I confuse the artists with the characters and characters with exhibition sites, or perhaps that is the point; to let my imagination run its own course. Together, they form my image of the Professor, the Coalman, the Moped Rider, the Tourist, the Fortune Teller, the Bonimenteur, and an Acrobats. The cast of Afif’s Bergen Assembly. And together these characters are to merge into a heptahedron; a seven-sided shape—my heptahedron. A multifaceted concept that is used as the storytelling device in the perennial exhibition to connect the presented artworks (old, new, and commissioned) to our current world. Taken from the unpublished (imaginary) play, The Heptahedron, written by Thomas Clerc that is (supposedly) based on a performance of a geometry class by Afif for the 2014 Marrakech Biennale (see the possibility for the consciously imposed yet profound confusion). This form, evokes both mathematical and apocalyptic associations, literally shapes, and conceptually thematizes the third edition of Bergen Assembly. Each character is linked to one of seven sites and each site shows three participating artists. A conglomeration of layers that fold in on each other, challenging thought, yet facilitating navigation.

Flag for Yasmine and the Seven Faces of the Heptahedron

© Bergen Assembly 2022, Convened by Saâdane Afif and curated by Yasmine d´O. Photo: Nicolas Rösener

Afif, as convener of the triennial, in turn invited Yasmine d’O as its curator. It is d’O who gives substance to this Heptahedron; the artists she curated into the shows flesh out the geometrical skeleton. As can be read in her curatorial statement, d’O had also been thinking about the idea of a solid body with seven faces for some time. Of course, she turns out to be (semi-)fictional too—on a webpage that sells clothing items on which Afif collaborated with Star Styling, I read that Yasmine d’O may refer to Yasmine d’Ouezzan, the first woman billiards champion of France in 1932. Although, not much information is found when further research concerning this fragment is conducted. Nevertheless, Yasmine, whoever she may be, is a crucial figure in the narrative of the exhibition. Having the Bergen Assembly titled after her, introducing her as the protagonist of the curatorial narrative under the same name as well, she becomes a symbol for the myriad paths through which one approaches the exhibition(s).

As in all plays, there is a certain order of appearance of characters, although it is not mandatory to abide by in this case. And as often when consumed by a narrative, I cannot help but to have a favorite character. In Bergen, I visited each of them, spent time with their origin stories in the curatorial room at Bergen Kunsthall and with the works they are assigned to host in their locations. Although all characters resonated, each very aptly responds to current themes—questioning systems of knowledge production, acknowledging our human footprint, addressing climate crisis, highlighting identity politics, breaking gender boundaries—it was the Fortune Teller who kept calling me back. As fourth and middle character, tucked between The Moped Rider and The Coalman (arguably the strongest opposition between characters: freedom, movement and sidetracks versus death, old ways, and stagnation), spread across the spaces of Northing, an empty house, and a public open air listening booth, the Fortune Teller comprises the only non-institutional site. Jessika Khazrik, Miriam Stoney, and Alvaro Urbano are the artists that make up The Fortune Teller.

Khazrik’s interdisciplinary installation, ATAMATA, is presented in Ekko, a club in Bergen, which includes a seven-channel video, silver-colored material covering sculptures as well as the club’s architecture, a series of interstellar raves, and a four-day music and performance program that “re-addresses club spaces as templar and serendipitous places of techno-political congregation and collective attunement with an ability to re-create and host different times and desires into the present.” The club becomes a social place not just for fun, but to celebrate, elevate, build, and change community; club as a place to call out and be heard. In an artist talk, Khazrik explained that the etymology of the Arabic word for ‘club’ returns the meaning to “calling,” while pointing out that silver as a color reflects rather than absorbs, multiplying what is present around. The affirmation we hear you, we see you is given additional dimensions in Khazrik work.

Across the street, in the abandoned rooms of Østre Skostredet 8, Urbano re-installed his work The Great Ruins of Saturn (2021). With the lights turned off, one steps into and becomes part of a performance in progress upon entering the old wooden home; shadows of small metal sculptures dance on the wall and inevitably on anyone stepping among them. While reminiscent of children’s projection puppet lamps, these sculptures also include stars and planets, the majority of the imagery are symbols of capitalism: dollar bills, UFOs, skyscrapers, futuristic cars, the Statue of Liberty, and the famous Unisphere. They directly refer to presentations, thoughts, and imaginations seen at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, of which some architectural ruins still remain unused in Queens’ Flushing Meadows Corona Park. Now disassembled, the remnants of the fair speak to one of the themes in Urbano’s practice: the longevity of the idea of future. What has become of these futuristic plans driven by corporate greed and capitalist gain? Originally made for Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York, restaging the work in a ruin of Bergen, Urbano allows for the future to be reimagined again and acknowledges the cyclical understanding of time: that what was once future is now past.

Installation view from Alvaro Urbano’s exhibition The Great Ruins of Saturn for The Fortune Teller, 2022 in Østre Skostredet, Bergen. Courtesy the artist. © Bergen Assembly 2022 convened by Saâdane Afif and curated by Yasmine d´O. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

It is not possible to hide from the future, perhaps similar to the way debt will catch up to you eventually. Stoney was commissioned to create a new work for the Bergen Assembly, for the Fortune Teller in particular, and so she wrote a book-length poem called Debt Verses in the voice of the Fortune Teller about debt and indebtedness. The poem is written in English and translated into Chinese and Norwegian, all languages appear alongside each other in a truly beautiful, harmonica foldout design with a magnetic cover so that it can be opened and read from two sides while remaining one book. This physical layering of the publication follows the structure of the narrative. Aside from commenting on credit lines, college loans, and debt collectors, seemingly fictional structures are voiced through bureaucratic auto messages, but in reality with the power to kill that haunt and settle into the fabric of everyday life, Stoney reels in another reality of academics and the acknowledgement of knowledge that is borrowed, which she extensively footnotes. Sometimes seen as a hiding behind others, the extensive referencing on one hand points to the exclusiveness of academia, and on the other, how an indebtedness to the backbone of the women informing it has long gone uncredited. Presented at Northing Space, temporarily turned into a bookstore, selling just one book, Debt Verses, deceives us a little just like its collectors and any form of socially constructed belief system. But not for long, as outside, this ironic ploy is countered by the installation of a public listening booth on Østre Skostredet, giving any passerby access to a full-length audio recording of the poem by Stoney.

Debt Verses, book signing by Miriam Stoney as part of Miriam Stoney’s exhibition Debt Verses | Vers om gjeld | 赋债, 2022 for The Fortune Teller, Northing Space Bergen. Courtesy the artist, Northing Bergen. © Bergen Assembly 2022 convened by Saâdane Afif and curated by Yasmine d’O. Photo: Yilei Wang

Whether conceptually or visually, each of the Three Fortune Tellers’ works is a call for visibility or immediate inclusivity. Silver-reflecting walls and daytime club hours in Khazrik’s work, shadow and light play in Urbano’s, as well as the act of re-predicting a formerly imagined future, and the literal highlighting of others’ texts informing one’s writing in Stoney’s poem are among some examples making this call tangible. It makes sense that in uncertain times of pandemic, war, raging gas prices and a declining economy, an insight into the future is most wanted now. This attitude, however, risks the future—the 1964 World’s Fair is an example par excellence—to turn into a commodity. Thus, when Afif introduced a Fortune Teller, she appears not to know what is to come, but as becomes so evident in Stoney’s words, to understand the guiding impact of the then and now on what will be. As the fourth character, The Fortune Teller is all of us, the rest spirals out of her. Beyond her call for a contemporary clairvoyance as opposed to a future one, all other characters, which I will leave for you to encounter, spread a message from their past or future positions: be here now. A seven-sided form is tricky to imagine, let alone perceive completely at once, and so the heptahedron becomes a very accurate allegory for the impossibility to see the future if we cannot even see around the corner. To see all seven sides, one has to move, one character at a time, until a fragmented whole can be pieced together from the different viewpoints obtained. Then still, the figure that appears, is subjective; combine all subjective perceptions and the rest spirals out of her. “Depending on how you choose to look at it, the ebb and flow of life is a continuum that is either circular or moves back and forth, rather than being linear.”

Bergen Assembly runs through November 6, 2022 in Bergen Norway.

Installation view from Jessika Khazrik’s exhibition, The Fortune Teller, 2022 at Østre, Bergen Courtesy the artist. © Bergen Assembly 2022, convened by Saâdane Afif and curated by Yasmine d´O. Light design: Shaly Lopez. Photo: Thor Brødreskift