text by Poppy Baring

Often described as a national treasure, David Attenborough acts as a grandfather figure to those who have watched his explorations across our planet, a wise adventurer who always talks with warmth and kindness while discussing a subject that is ever-growing in its melancholy. Our Story is a fifty-minute, immersive cinematic experience that takes visitors through the start of human life, to our present, and ends with a hopeful prediction of our future that can be achieved if we are willing to work together.

As summers pass, natural disasters persist, and the world’s balance seems so completely off-kilter in more ways than one, this experience, which explains the development of life and the continuous redevelopment of our world and its inhabitants, leaves your chest tight and heavy with emotion.

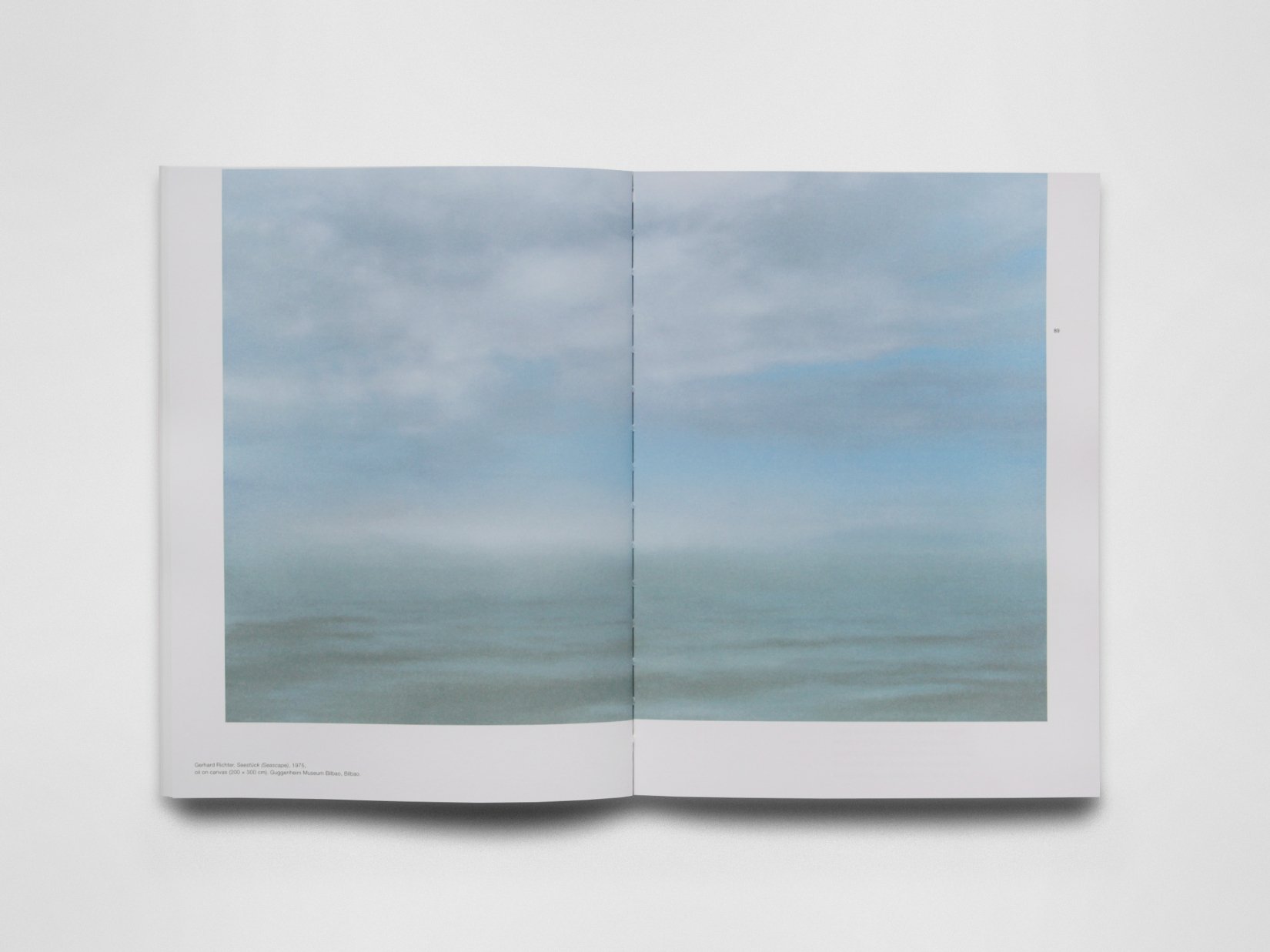

Audiences take their seats in a room full of stars projected onto the surrounding walls. The Hunger Games effect of a room made out of pixels is only felt while waiting for the show to begin. Once it does, you no longer feel surrounded by computers, but are traveling through space with the spark of life fully ignited. Stars begin to pass you, as do galaxies and planets, until we pass over the moon and reach our planet.

What is our significance? Attenborough asks. We are significant because the Earth is significant and the Earth is significant because of us, he answers. Earth is the only planet we know of that thrives in the way it does. Once unable to support life because of its unstable climate, Earth changed when temperatures became predictable and microbes expanded in their complexity. With every asteroid attack, to which Attenborough explains there have been at least six that have led to mass extinction, the last of which was 66 million years ago, our planet rebuilds, and with it so do new biospheres.

After coming face to face with gorillas, being immersed amongst hunter-gatherers, and being told the hopeful story of how great blue whales were saved from extinction, we are brought back up into space with humans’ first mission beyond the atmosphere. This was the moment we gained perspective and the first time humans saw Earth from afar, allowing us to see our home as vulnerable and finite.

Somehow, this perspective, described by astronauts as “the overview effect,” has not been enough to create an adequate change in our behaviors, and today we ourselves are responsible for disrupting Earth’s balance. The show, however, ends with a hopeful message: we can make a difference. We are all important, and there has never been a more exciting time to exist on this planet. David Attenborough sits in a chair to talk face to face with visitors, and there is a feeling that when he is no longer here, the hope that he brings to this conversation will fade, and we will all be left fully responsible, with no grandfatherly comfort to soften our fate.

Our Story is on view through January 2026 at the Natural History Museum, Cromwell Rd, South Kensington, London SW7 5BD