interview by Oliver Kupper

Barbara “Bobbie” Stauffacher Solomon, now ninety-five years old, studied graphic design in Switzerland under the legendary Armin Hofmann in the late 1950s. Her most famous project, the graphic identity for Sea Ranch, a planned community imagined by architects Al Boeke and Lawrence Halprin on the Sonoma Coast, was a blend of Swiss Style and California Modernism, an amalgam of irreverent hippie cool and clean straight lines in oversized texts and symbols called ‘supergraphics.’ The logo depicted two sea-shells that formed a ram’s head. When the idealism of the ‘60s and ‘70s died down, Sea Ranch lost its utopian ethos, but still remains a relic of what could have been. Solomon, however, is more prolific than ever.

OLIVER KUPPER: Right now you are working on some new supergraphics for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

BARBARA STAUFFACHER SOLOMON: Yes. I'm doing absolutely enormous “OKs” with stripes. We're going to make it so visually nuts. It's like choreography, where you get everybody to walk in one direction with the design.

KUPPER: Like the old dance step footprints that would be painted on the floor.

SOLOMON: Yeah, kind of like that! Only it'll be on the ceiling. “OKs” will lead you to the Mario Botta building. So, people will go through the “OKs,” which is where the information and tickets desk is, but then they get into this kind of maze of stripes.

KUPPER: You have also been working on a series of books, like UTOPIA MYOPIA (2013), which has a page that is a five-act play set in Hollywood, between angels and palm trees.

SOLOMON: That one section is totally illiterate. I never went back and cleaned it up, or I just gave up and decided nobody's ever going to read this, the type is too small. But you did!

KUPPER: I dissected it immediately, because the lore of Hollywood attracts me. Did you spend time in Hollywood?

SOLOMON: I've been down there a lot—with my first husband who was a movie maker, Frank Stauffacher. All the screenwriters loved him. That’s how I knew George Stevens and Frank [Capra], who was an angel! My husband, who had a brain tumor, started fading after he presented one of his movies. We went out for a drink, and my husband passed out. Capra, a strong little Italian man, just picked my husband up and carried him to the car. I mean, he's a mensch. We knew them towards the end when Frank was dying, and we were quite a scene. I was this beautiful little chick, and he was handsomer than the movie stars.

KUPPER: That was the golden age of Hollywood.

SOLOMON: They made the American Dream. For Capra, it was the American Dream to get out of Italy and the mess there and live in Hollywood. And make these democratic movies, teaching everybody to be good little democrats.

Barbara Stauffacher Solomon, Supercloud 22, 2020

Mixed media: Pigment print collage, gouache, ink, graphite,

colored pencil, white-out, cellophane tape, rubber cement, paper

8.5 X 11 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

Courtesy the artist and Von Bartha

KUPPER: Did you ever meet Man Ray and what was he like when you met him?

SOLOMON: Oh, he was sweet. He never said anything. He only talked about money. He was always short of cash. He always wanted to sell a drawing or a painting. He always wanted to have the next show because he needed money. We had dinner at their house one night, and Julie Man Ray was teaching me how to make risotto in the little kitchen. Think of yourself out on the corner of Hollywood and Vine and just walk about six houses south, and that was where they lived. That was in 1948. We went down and saw them on our honeymoon. And we took a walk around the block to look for the sites of where all the novels had been written. I was very young. I was sixteen when I first met Frank [Stauffacher]. He was fifteen years older than I was. He was fancy, and he knew all the surrealists.

KUPPER: Where did you stay when you were in Los Angeles in 1948?

SOLOMON: I would always stay with Lee Mullican and Luchita Hurtado. All the men were madly in love with her. She was so good at being charming, and she was just marvelous. She had been my best friend since I was about 16. I mean, she would tell me what to do, and I would do whatever she said. We were very close. They had a glass porch on the front of their house with a little cot in it. It was about three-feet wide. That was my bed.

KUPPER: Wow, that’s an amazing memory of Luchita Hurtado.

SOLOMON: I didn't even know she had her own last name. She was either Luchita Paalen or Luchita Mullican. She had so many husbands and names. And as long as the men with their egos were alive, they were the painters, and she was the one who cooked dinner. She never really let herself paint until she was a widow and had time. She always knew she could, I think, deep down. And the minute that Lee died, she started doing it, and then she was immediately very successful.

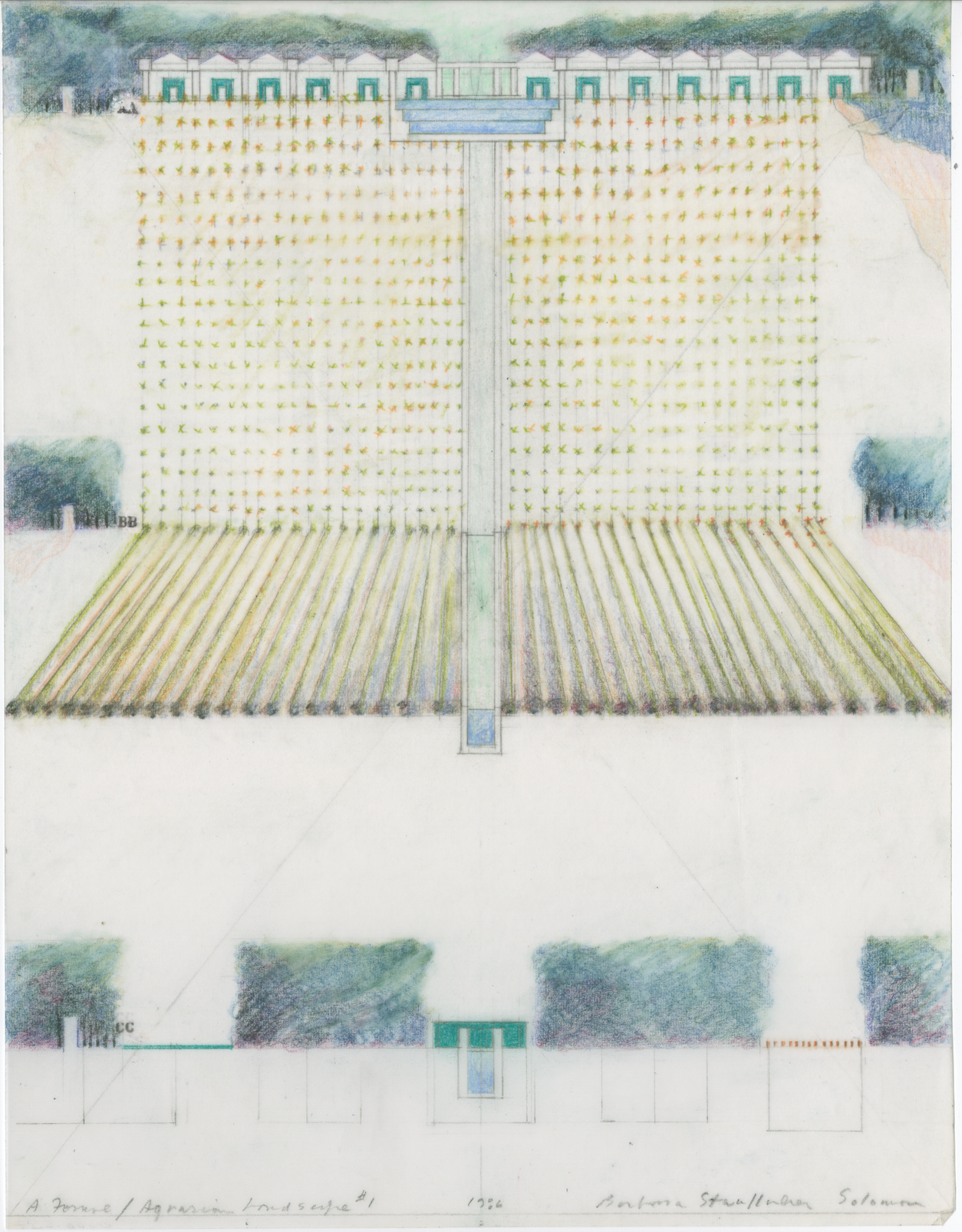

KUPPER: I wanted to talk about your thesis book, Green Architecture and the Agrarian Garden [1981]. Why is the union of architecture and landscape so important?

SOLOMON: It's everything. They are two sides of one wall. First, the architect destroys all the trees and builds his precious little house. And then the landscape architect comes back and puts the trees and nature back. The world is all one big landscape. Inside the house and outside—they're all one thing in a way. They're extensions of each other. But in the architecture department, they hate each other. Architects think the landscape architects are the stupid ones who didn't have enough brains to be architects. And the landscape architects think the architects are the shits that are tearing down the trees.

KUPPER: Well, a lot of architects are building now with more organic architecture in mind, where the landscape is more seamless with the architecture.

SOLOMON: Well, the landscape architects have won. The landscape architects are going to save the world because otherwise, it's gonna get too hot, and everybody's just going to burn up.

KUPPER: When did you start becoming interested in green architecture?

SOLOMON: Somebody in art school once said, “Never use green. It's a very hard color to deal with, and never put empty space in the middle of your painting.” So I did both, actually. I have hundreds of those goddamn green architecture drawings. The ones with square trees that look like buildings. I just visually like green rectangles and want to make the world look that way. I was born in San Francisco and I lived all my childhood in the Marina District where there's the Marina Green. Every night with my mother, we'd walk around the Marina Green. And the grid of San Francisco has all these green squares where there are parks scattered around. At a certain point, the tops of the hills were just too difficult to build on, so they made them into parks. Little rectangles on top of almost every hill.

KUPPER: San Francisco is such a beautiful, green city. And the surrounding areas like Marin. The utopian ethos has been so strong in California. Why do you think that is? And what does utopia mean to you as an architect?

SOLOMON: All architects think they're building utopia. Even if it's just a gas station, they think it's utopia.

I just think California is—I mean, open your golden gates! Since we found gold here, they assumed California is utopia. Californians have that feeling about California. That's why I came back. I could have lived in Europe. California is just an extension of people's bodies.

KUPPER: Where do you think your rebellious spirit came from?

SOLOMON: I don't know. My father was a lawyer, and he told me there's no such thing as god or the president of the United States. Don't have respect for any of those things. So, there's no reality. There's nobody you believe in and listen to. It's all absurd. My mother was like that too. She was a pianist. She was a rich girl that was no longer rich and loved walking among the redwood trees. She thought god was in the redwood trees.

KUPPER: Can you tell me about Sea Ranch, and your contribution with the Supergraphics. When did the Swiss Style start to merge with the California Modernism?

SOLOMON: When my husband died in 1955, I went to Basel, Switzerland to learn how to make money and how to be a designer instead of just a painter. I came back with all this training in me when they handed me Sea Ranch in 1962. Al Boeke and Lawrence Halprin, two of the architects, wanted Sea Ranch to be like the French new towns. Also, Lawrence had been raised on a kibbutz in Israel. First, he gave me an office that was in the same building as his firm. When they told me to do Sea Ranch, I designed it the way I had been trained under Armin Hoffman at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Basel. I had no idea what I was doing until I did it, I have to admit. But I was such a modernist. I went up there in a truck with the two sign painters. Everything had to be straight lines because they were sign painters and could only do letter forms. So my vocabulary consisted of what a sign painter could do. I started with that big blue wave on the west side of the building. The wave went up the shed roof, and then it came down, turned green on the other side. We only had black and white, vermilion and ultramarine blue, and I think one small can of yellow—primary colors. It was kind of like De Stijl. I was best friends with all the architects until I got all the press. Charles Moore never spoke to me again because I got in Life magazine and forgot to tell them he was the architect.

KUPPER: So, who did they hope would live in Sea Ranch? Was it supposed to be for artists, for intellectuals?

SOLOMON: No, Al was very square. I mean, it was supposed to be just plain old nice people. They weren't supposed to be intellectuals. And it certainly wasn't supposed to be second homes for the rich. That happened when they started making it so you could save on taxes with your second home. And that's when everybody was buying second homes up there. And they hired a couple of salesmen to come in and take over selling off the land. All of a sudden, it wasn’t about a nice town with a church and a school.

KUPPER: Sea Ranch is really an example of an almost failed utopia.

SOLOMON: It really is. It's very successful if you're rich. A lot of people from Los Angeles are coming up and buying property. Now it's all diamonds up there and the richest, trickiest people.

KUPPER: Do you think design can be dangerous, especially if you are designing for a dangerous philosophy?

SOLOMON: Of course, but that's what design is: it's the bullshit on top. It's making things look good.

KUPPER: That's a good answer. I wanted to ask you if there is any connection to your time as a dancer and graphic design?

SOLOMON: Every once in a while, it used to feel like it. When I used to work with the crew, and when you stretched your body big and long or got on the floor, I felt like I was making the same moves I made as a dancer. You're kind of moving with the paint with your arms stretched out. And you know, where I feel like a dancer again is when I’m at the SFMOMA making these stripes that'll make people walk from the entrance and up the stairs. They’ll wonder, now what am I supposed to do? And now, I'm going to give them big red stripes to have something to do. I’m choreographing them with art.

KUPPER: Looking back on your career, what's the one thing that's been most misunderstood about you as an artist?

SOLOMON: Well, nobody remembers that I was a widow with a child, and I needed money. The whole damn thing has been to support myself and my child. My husband, who died, his family just dumped me because my daughter has cerebral palsy. They were scared I'd ask for money. Then my second husband dumped me because he was young and cute. I aged, and he seemed to not. And I always had to support myself. I had two daughters, and I have a granddaughter. It was like, "Grandma is painting some supergraphics. I guess we can have oysters tonight!” If Frank hadn't died, I would have been a painter. And if I hadn't gone to Switzerland, I probably would have painted big color fields.

KUPPER: Well, I'd say you came out on top.

SOLOMON: Look, I was talented. I mean, when I had those two big rooms in the Sea Ranch to do, I was lucky, I got Charles [Moore] and Bill [Turnbull’s] architecture. The walls had beautiful shapes, and I just followed the shapes and played with the shapes, and thank god it came out right. It's just dumb luck if it really works.

KUPPER: Do you have any advice for people who might be reading this and thinking about building a better word; their own utopia?

SOLOMON: I remember when I was teaching at Harvard, I asked the students, "What is art?" The answer: "It's nothing; just learn to see, and you'll learn that everything is art." The problem is that people look, but they don't see. If you look and see, the whole damn thing is certainly art.