TORKWASE DYSON In your work, there are so many different movements. I’ll say acrobatics. To quote Brand Nubian a little bit, “acrobatics over beats.”

DEREK FORDJOUR I really like the notion of the acrobatic. As you talk about the dexterity of bodies and being pushed, I think about the presence and absence of bodies in your work. This is really a big part of my attraction to your thinking and your work as it relates to mine, is the absence of the depiction of the body, but your keen awareness of bodies in space. I wanted to know from you: where is the body centered in your thinking absent from depiction of the body?

DYSON Well, I understand consciousness to be experienced through the body, in this form as a human, right? As a human, sentient being, consciousness exists because of the body. And then the history of consciousness, liberation, Black liberation specifically, I understand that the brain and the mind are doing things that the body then follows, or catches up with, or responds to. What that does is that puts into ways of thinking and moving around instinct, around perception, around ideas of logic. I was thinking the other day about the differentiation between perspective and space. For me they’re indelibly tied; there’s no absence of the body ever. So, when the work is functioning, when I’m really functioning at a high level in the studio, when I’m drawing, when I’m painting, when I’m making sculpture, I am aware that the body is a place for my consciousness, and my consciousness is a place to understand past, present, and future, and that Blackness, in particular, is a condition of consciousness first for me.

FORDJOUR And consciousness is a product of the mind it seems. When you think about the brain versus the mind, and for you, does Blackness also exist in this realm?

DYSON Consciousness is something that happens between the brain and the mind in the human form. So you have the brain, which produces a consciousness. The brain, to a degree, is measurable. The consciousness is something that is indeterminable, that is formless. When we’re thinking about Blackness and being, and understanding those things, our experiences with body and mind are inextricably tied to the history of becoming Black, becoming human, becoming present. So, these things aren’t separate.

FORDJOUR I love the idea that there is never an absence of the body, that the body is always present. I was thinking about how drawing, to me, is very connected to thinking. It’s almost a form of thought mapping. I think drawing in your practice plays a significant role, whether it’s the drawn line or actual mapping/graphing. I thought about the fact that I use lots of charcoal—that’s how the work begins ... the drawn line, which is a form of consciousness as well. When you talk about the expansiveness of consciousness and how it is ultimately indeterminable, the vastness of potential at the beginning of a drawing, the openness of possibility, is what we are attracted to...potentiality. I really think alot about the role of drawing. I am aware of your practice of making a multitude of small studies and expanding the possibilities of line—I’m now thinking about that gesture as evidence of thought, and a kind of stream of consciousness. Do you think about drawing related to consciousness or thought?

Torkwase Dyson

Distance, Distance (1919: Black Water), 2019

Acrylic, metal, ink, and gouache on wood

(diameter 98 inches/ 248.9 cm)

©Torkwase Dyson.

DYSON Remember when we were at the Graham Foundation and you participated in the drawing workshop, and you were drawing with chairs, and you were putting chair legs through pieces of paper, and you were making marks on them? Drawing in the expanded field is that kind of action where mindfulness, thought, improvisation, thinking through equation takes place. The act of the brain thinking one plus two equals three is different than just thinking of the number three, right? Those kinds of ways in which the mind and brain are capable of both linear thought, and instinct, and expression around knowing are always operational when drawing. When you’re in the studio, and you’re making, you can set yourself up for both. You can set yourself up to understand an equational theory. You can understand a kind of mathematical abstraction with geometry. You can set yourself up to understand the curvilinear and the rectilinear in an equation. You can also set yourself up for improvisation. You can set yourself up for ways of knowing through the body in a kind of immediacy. These capabilities are, if we think about understanding as a dialectical experience, then everything kind of goes. It’s those kinds of ways of working that put you in a position to exhaust the possibility of a form.

FORDJOUR As you talk about the possibilities of setting up a kind of calculus in the studio, I think about your legend of shapes (box, bell, curve, etc.) I really loved that you not only had this legend, but you made it available for viewers. This could have remained limited to process or part of your enigmatic thought restricted to the studio, but you also made it available in the wall text. Was the creation of this legend, the genus of the work? Did you start with those elements, or did you react to the works and sort of discern patterns and then extract this legend? Did you ever have any concern about how people might apply it to reading the work in that it could become possibly reductive?

DYSON Well, I don’t know if it works like that. First and foremost, I’m interested in, as a reductive kind of phrase, environmental liberation—the future of it, the past of it, and the history of it. I needed to, in my studio, create, I’ll call it a Black and eloquent equation to think about the strategies and the methodologies behind those futures. Because I believe it is the essence of those liberating acts in combination with the reality of indigenism that is going to save our future. The work is only about me thinking through that and making objects so that I can be in that conversation consistently and insistently, there is a level of comprehension around those possibilities that make me feel alive, and that regard all those histories as living histories, and regard the future of the human race as something that is unfixed and constantly changing, and for more improved living conditions. One doesn’t come before the other, I don’t think. I’m just trying to get at these things. Maybe they came at the same time, I don’t know, but what I landed on for that show is a solitary form. The curve, the triangle, and the 90º angle is where I started years ago, and now I’ve created a single form that I believe is my own. The trapezoid in relationship to the circle creates a trapezoidal prism and a volume. When I was, rightfully so, using the history of Black liberation politics to discover myself in the world and have conversations, I now landed on a form that, in itself, I can insert things in. Do you know what I mean?

FORDJOUR Oh, absolutely. I want to go back to a point in an exchange we had this past summer. I asked you about Afrofuturism, and you gave a flat rejection of the presence of that kind of aspiration in your work. We don’t have to talk specifically about Afrofuturism, but this notion of futurity as something optimistic and hopeful. There’s always this kind of vacillation between historical precedent and events and also a sense of propositions for the future in your work. I would like to know whether your understanding of the idea of futurity, particularly how it emerges in your work, whether questioning or even conjuring it—is optimistic?

DYSON I don’t work in those terms, I guess another flat rejection. I recognize them as ideas—propositions that other people use to move forward, but I think about ideas of impermanence, creativity, invention, and advancement. When I meditate, I think about change, and I think about advancement, I think about ancestors, I think about the specter, I think about horror, I think about peace—I think about these things, so I don’t use those phrases because...I don’t know why.

FORDJOUR Because they’re limiting?

DYSON Maybe not. Maybe they’re not limiting. I just entered this idea of the future through a different door. I entered a door through someone like Roscoe Mitchell, so when I see Roscoe Mitchell set up, ready to go, I don’t think about hope. I think about preparation, I think about skill, I think about risk, I think about transformation, and it gives me a feeling of velocity, and I know that things are always moving and expanding.

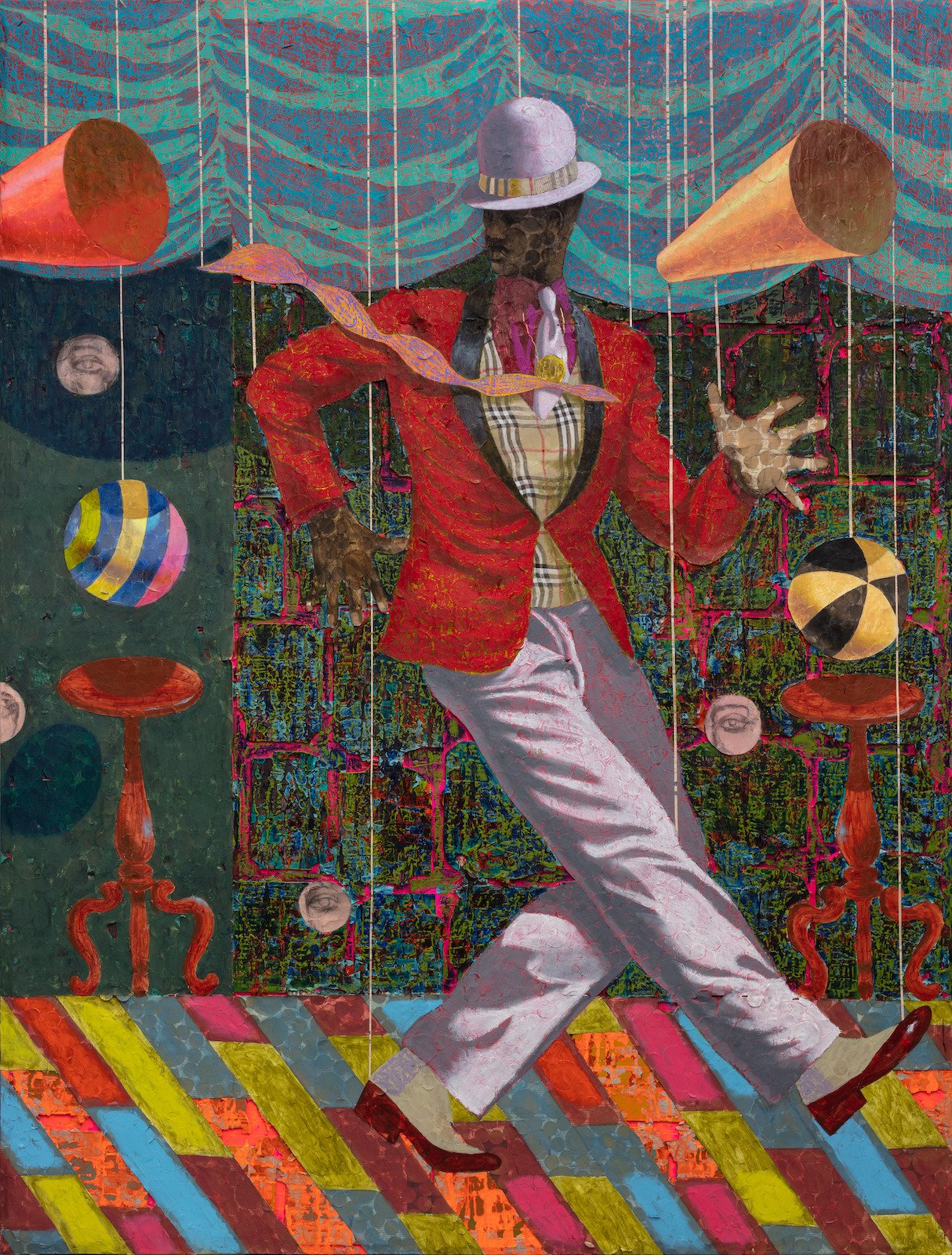

DEREK FORDJOUR

STRWMN, 2020

Acrylic, charcoal, cardboard, oil pastel and foil on newspaper mounted on canvas

85 x 65 inches (215.9 x 165.1 cm)"

Image courtesy of the artist and Petzel Gallery

FORDJOUR This is how you approach…

DYSON That conversation about Afrofuturism. Thinking about your work—I want to know what you think about imagination, and invention, and aspiration, and collective being. How do those things operate in your work?

FORDJOUR I really think about how inventiveness is a necessary aspect of the Black condition. To be an under resourced, largely oppressed people, or at least, people navigating the conditions of oppression, invention becomes a strategy for survival. As it pertains to my work, there is some degree of an element that might be read as whimsy, or a hint of the preternatural or the magical, the carnivalesque, which kind of pushes toward a kind of spiritual dimension. I’m really aiming at that sense of wonder around invention, and it happens for me in very practical terms when I encounter systems of oppression. Even prisons for example, how there’s an ecosystem within that system of oppression that can create all this contraband of many sorts that then has an economy. But then when I go to South Africa and go through a township and find out that there’s some sort of drug that’s been created by rubber in a lantern, and this other thing that creates another sub economy. I’m really interested in how—around the world, in order to thrive under oppressive conditions, people become inventive. We must become educated bodies, Black bodies in institutions, and still interested in liberation, and negotiating all the things that come with that. I think in this body of work, to more or lesser degrees, that sense of whimsy is reaching for that inventiveness that is a magical dimension that I associate with Black culture.

DYSON Just thinking about the installation that I’ve seen of yours—I’ll bring up the specter again—where there’s an amalgamation of the meta, the exact, the specter, the in-between, the acrobatic, the practical, the mystical, but also this idea of the indeterminable, and a real sense of time in your work as well. I was thinking about one of your animatronic devices that circles, spins, and lights and moves, and the sense of time that it takes and steadiness that it takes to create a genius movement, to create something that’s at the edge of its absolute possibility. There’s something about your work that happens in that space without leaving behind the history and the terror of the carnivalesque—Black history specifically, and global history more generally. I’m really, really fascinated with each of your projects, how you continue and have a fidelity to the mechanistic while holding onto the quotidian. I know that in a few short years you’ve made these leaps and bounds. I’m super excited to see where it all continues to grow. The rigor in your practice really shows within experimentation, and invention, and materiality.

Torkwase Dyson

I Am Everything That Will Save Me (Bird and Lava), 2020

acrylic and string on wood

36'' diameter

© Torkwase Dyson, courtesy Pace Gallery

Photography by Kris Graves

FORDJOUR Very much in materiality and the haptic, right?

DYSON The haptic, yes.

FORDJOUR The haptic as a way in. I think that the paintings now are much more active, that the figures are more animated. I haven’t really depicted much action, but I really wanted to respond to this sort of social action moment in which we currently live--this moment of activation around election, responding to death, and images of them, and all of the excitement even in young people around addressing the Black condition in a way that I have not seen in my lifetime--this convergence of social action. And there’s always been liberation work, there’s always been work toward revolution, but this sort of crystallizing moment where it’s at the fore and goes beyond the bounds of our community conversations, and now there seems to be a world community that’s motivated around Black liberation and seeing these things come to the fore. There’s an activation, and I really have wanted to have work that felt invigorated and that would probably explain the move toward the acrobatic.

DYSON And pushing against fascism.

FORDJOUR Certainly. Listen, absolutely. Honestly Torkwase, fascism was a theoretical idea or far off political concept for most of my life. It was something I accessed through literature and learning. It was merely another form of government, but to experience that, to live it, to understand it, and to feel the anxiety around danger for bodies in a governmental system and that kind of thing—this is the first time I’ve really experienced that so keenly. The acrobatic—which is a great way to describe some of the physicality and the gesturing that happens with my figuration. It is the acrobatic toward a kind of discomfort and a contortion, a contorting within, thinking about the edges of the picture plane and activating portraiture or bodies. Some moments, of course, are very still, but I have moments that go in the direction of action, and I think it is informed by our moment of political action and awareness. One of the things I really appreciate about you as an artist, but also as an educator is your vast knowledge and appreciation of a multiplicity of practices. You are not an abstract painter. It is far too reductive for you. You are able to really plug into practices of a variety of modes, and your understanding of what’s happening in figurative work, my work, and my deep understanding of what’s happening in your work, but we fall into different categories, the objective and unobjective—I want to know about your relationship to figuration. You started from the mechanics of drawing, originally. You really refused this splintering that happens around figuration and abstraction. But I wanted to just hear you talk about your relationship with the figurative.

DYSON In this moment of activation, and as you talk about witnessing firsthand, or being in close proximity to fascist, racist violence, brings us to a different kind of kinship of systems of global oppression. In thinking about the exhibition Freedom Principles, these are the principles which I am operating under, where there’s nothing too far, there’s nothing too distant, we’re all in this condition of the relational, and we’re all in this condition of consciousness together. Now there are registers of closeness, like my closeness to immediate death and violence. Am I far from what it means to have my child kidnapped from me and then held in cages? The politics of the human body are never without question, whether we’re talking about figuration or non-representation, or kinds of concrete abstraction, or didactic abstraction, all of these things are in consideration in terms of the way that I think about artmaking between the mind and the body.

FORDJOUR I’m so happy you have a piece, by the way.

DYSON Yeah, it’s right over there. You see it?

FORDJOUR That’s like the first sculpture I ever made.

TORKWASE DYSON Could you talk about your upcoming show?

DEREK FORDJOUR I had a year knowing that I was going to do this show. I spent a long time thinking about it before actually doing anything. There’s a collaboration where I’m working with a puppeteer, Nick Lehane, so that required lots of meetings. I was also learning about the art form of puppetry, which I enjoy. And then there were sculptural elements that are happening in different places, due to Covid, which required thinking, fabrication, and various processes. I waited until those things were happening before the painting began. I found that the aspects of learning and the collaborative work helped activate many of the ideas I had been processing before. I had this list of painting ideas that was constantly evolving, but it wasn’t until I had these other things to react to that I really found an entry point. I probably work best extemporaneously, so maybe I was just creating the conditions for that kind of energy.

Torkwase Dyson

Space as Form: Movement 1 (Bird and Lava), 2020

acrylic on canvas

40-1/4" x 48" (102.2 cm x 121.9 cm)

© Torkwase Dyson, courtesy Pace Gallery

Photography by Kris Graves

DYSON Can you talk about the title Self Must Die? I want to talk about code, I want to talk about autonomy, and I want to talk about presentation. Can you talk about the title?

FORDJOUR Two things really brought this about. One, I was thinking a lot about death this year because I have been so proximate to it, just people struggling with how to pull off a funeral at this time, so there is the literal loss of life, people actually dying, this year. I also have a close relative who is dealing with a terminal illness, I have a son who is a twenty-two-year-old college student in Atlanta that was in the streets when protests were happening, and I watched two young people from the college he attends get dragged out of a car and tased violently by a mob of officers in riot gear, so thinking about his vulnerabilities as a young Black man at twenty-two years old. Also my father is in his mid-seventies, so as we think of end-of-life issues, I kind of sought safety in the middle, but then I realized that I am the same age as George Floyd at the time of his vicious murder. So I’ve been thinking about death in all these ways—the funerary, the absence of the funerary, living in the wake of death and also a very necessary ego death.

DEREK FORDJOUR

Pall Bearers, 2020

Acrylic, charcoal, cardboard, oil pastel and foil on newspaper mounted on canvas

100 x 72 inches (254 x 182.9 cm)

Image courtesy of the artist and Petzel Gallery