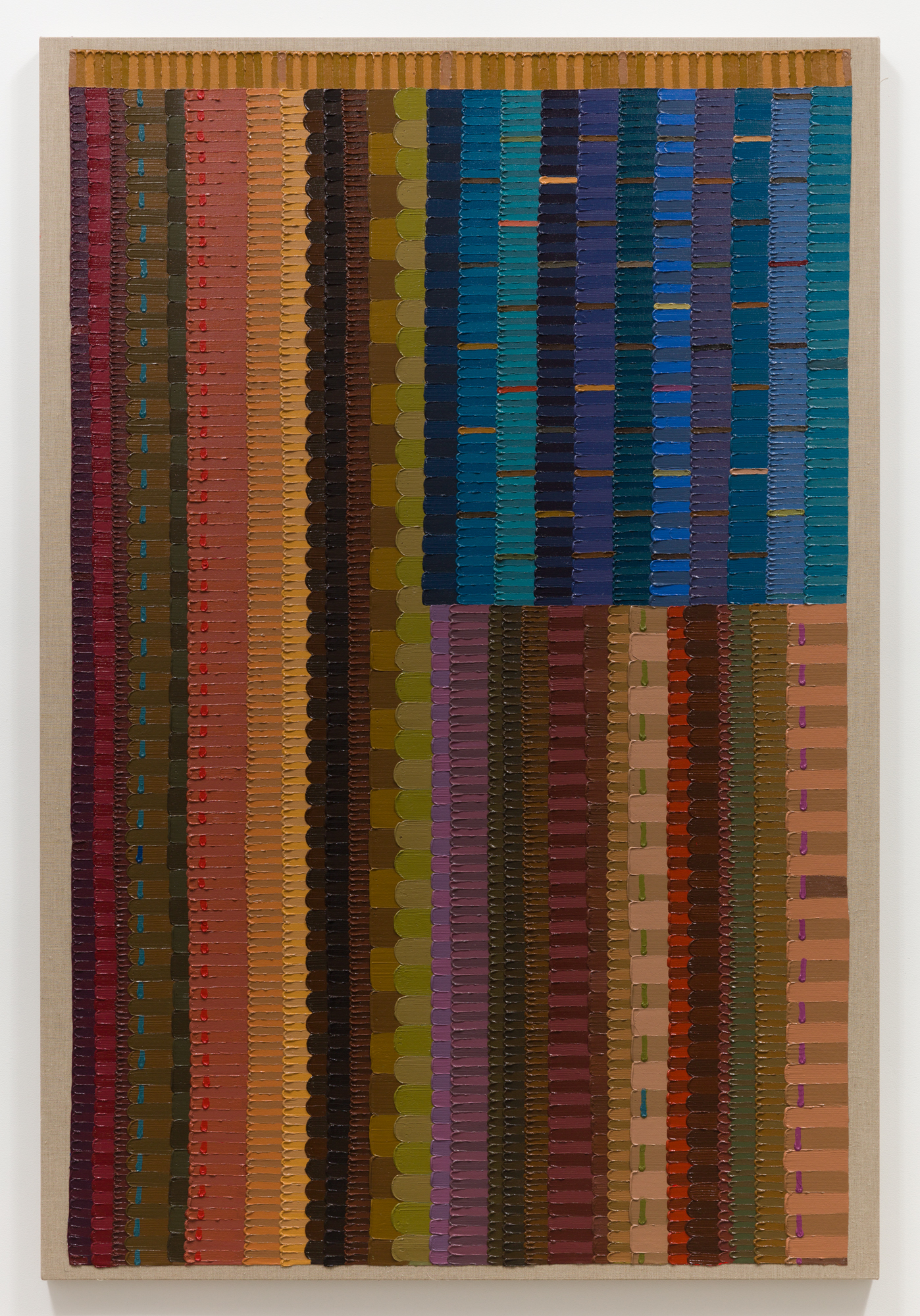

Album cover for Dreamstate

Image courtesy of Huxley

Photo credit: Samuel Bradley

interview by Mia Milosevic

Dreamstate breathes life into the experience of being human through electronic synths, poetic sonics, and an adeptness to color purportedly infused in our ether. Pioneering the electronic sound alongside revolutionaries such as Björk, Kelly Lee Owens has emerged as a maestra of techno. Tactfully and seamlessly blending drum and bass into a Berlinesque rave set, Owens punches the ceiling of what many understand electronic music to be. Her urge to go higher lays at the core of her latest album, which elementally fuses the concept of air into its resonance. Owens’ embrace of what it truly means to dream underpins the emotive beats which transcend her audience.

Dreamstate is out on Friday, October 18th via dh2/Dirty Hit.

MIA MILOSEVIC: First of all, congratulations on the upcoming release of your album.

KELLY LEE OWENS: It's still a mad feeling. It doesn't matter how many times you do it, it's like a child and the child's gonna go out into the world by itself for the first time. It's exciting. And it's nerve-racking. Creating something from nothing takes a huge amount of life force energy, as it should.

MILOSEVIC: Tell me about the title of the album, Dreamstate.

LEE OWENS: Well, it's an interesting one because I wrote the songs first, and I came up with the name and the title last, but then I found a photo of me last summer in Wales when I was playing with the Chemical Brothers, sitting on a graffiti wall that says “dreamstate.” So somewhere that must have really gone in. I was a daydreamer, my mom used to call it “Kelly's World.” I didn't know that until recently. It's always been a thing that's potentially deemed as a derogatory term. She's always daydreaming. But actually, it's so important. I just feel we're at this strange time in history with technology, so to be grounded and to dream with oneself is more important than ever. Also, to come into spaces with others and be able to transcend while you're awake is definitely what I'm interested in.

MILOSEVIC: I see that for electronic music, and especially with your music. I love the idea of your work kind of fighting the urban edge of techno, because you bring a lot of humanness to it.

LEE OWENS: I think it's about accepting both the light and the dark edges of yourself. There's this Murakami quote, which I always butcher, and it just basically says that when you're feeling high and good, go to the highest, furthest point. I often think of this album as the element of air. For me, every single album I have is a different element. But this one elementally is air, so there's lots of themes of higher rise.

MILOSEVIC: What’s your attraction to electronic music over other genres?

LEE OWENS: It was such a visceral moment when it happened, actually. It was during the Drone Logic sessions with Daniel Avery and I was in this incredible studio called Strong Rooms in Shoreditch, which is still there. I think what's interesting about that place is that lots of different types of music have been made there. The Spice Girls made their first album there. I grew up in the '90s, so I was like, oh my God! They used to practice their moves in the courtyard, apparently. And then there was a little old me, this girl from this village in Wales, witnessing synths and electronic production in action. I very quickly wanted to be a part of it because it was so tangible and visceral and totally an extension of yourself and your soul. I think it's Björk that says if there's no soul in the music, that's because you haven't put it there. Dance music can be cold or emotionless, some of it. I mean, it's so, so vast these days. But for me it was about fusing that emotional nuance and experience in there. I could create a song, but just in a different way than traditionally. I don't come from a traditional background in terms of reading or writing music, so that was never really gonna be a path for me. I just literally fell in love with the frequencies, the resonances, the sounds, the tangibility, and have been literally obsessed ever since.

MILOSEVIC: That's so cool. I do feel like there's a new advent of electronic music where it is becoming more and more emotional. Like with your music, with Fred again’s music, which I feel is blowing up for some of the same reasons, it’s electronic music with a very emotional aspect to it.

LEE OWENS: Totally. I think that it's people's storytelling. As time moves and electronic music has been around for a while, people can experiment in new ways. There's so much interesting electronic music now. It's not just one thing, which I personally love. I'm not a purist about it, but then there's certain things that will always make me tick—like anything that has an acid synth line on it.

Image courtesy of Huxley

Photo credit: Samuel Bradley

MILOSEVIC: Can you talk about the production of Dreamstate? I loved what you said about the making of the album being a collaborative experience, but also about how dreaming is generally synonymous with solitude.

LEE OWENS: It sort of started coming to me in 2022. The feeling comes first, the shapes and the sonic qualities that I think I want. They come early and I have notepads and I just write down the feelings and the colors. And it was actually brat green! This is 2022. So this is the thing, you're never alone in this. It's like we're all tapping into something collective and we all create our own versions of what's needed. I knew it was about a collective experience. And then going on tour with Depeche Mode in 2023 informed me again. I was inspired by the juxtaposition of anthemic moments, and then also super raw, vulnerable, intimate moments that actually Depeche Mode was so good at encapsulating.

MILOSEVIC: It’s crazy that you had the brat green color written down in your notes more than two years ago.

LEE OWENS: It's crazy because it just kept coming to me. I think it's Rick Rubin that says art is all there in the ether. And it’s just about who captures it and in what way. I've seen that recently, where there's this collective consciousness with artists. My cover for Dreamstate, it had to be blue. The amount of covers that have come out that have blue backgrounds! I just see these patterns and it's so interesting to me. I always bring it back to the Yves Klein photograph of him, a leap into the void where he's reaching for the color blue and he’s jumping off a wall to reach for this dream of capturing this perfect blue for the International Klein Blue. He's taking a leap of faith doing it. I found out that there were actually people Photoshopped out of that image who were there to catch him. And that's what every artist and person needs—community. You never do anything alone. It’s about the heights that you have to go to and the dreams that you have to at least try to reach for.

MILOSEVIC: It's like capturing the dreamstate.

LEE OWENS: That’s a good way of putting it.

MILOSEVIC: So the process is collaborative, but I’m fascinated by the idea of dreaming being something one does in solitude.

LEE OWENS: I did that for like a year and a half before I made a sound. That’s the notepad for me. That was me keeping the channel open and being with myself and being in nature or wherever. If an idea or a thought or texture came to me, I committed to writing that down and figuring out what it was. It's so important to create that space for yourself. Otherwise nothing can come through, no truth can be accessed. I'm talking about a very deep truth of something that's beyond yourself, that is collective. You can't truly know what that is for yourself if you're just on social media being told and sold what your dreams are and what you should do. It's harder than ever to not be literally influenced, as we know.

We're at such a strange point in history where we could easily go down a very dark path. We know that at least in the western world, mental health is a huge issue, and so to be proud of dreaming and daydreaming feels important. So for me, dreaming brings life to this experience of being human.

MILOSEVIC: I think that’s so interesting in the context of music, since music is this universal thing, but it mostly speaks to individual experience.

LEE OWENS: I’d say that's the ideal. I remember going to Berghain, I only went once, I played in the cantina next door, did a live show, and then I got escorted into Berghain, which apparently never happens. The guy on door was like, “Kelly?,” and I was like, oh my God, here we go. It was what felt like a cathedral of techno. What I always remember was that there were some groups of people, but a lot of people went alone. So they were alone together. They were in their own world dancing, not even looking up sometimes, for like hours. And yet, they were with their people through sound. That's really what inspired me. That was a long time ago, but it just stuck with me. I think that's a form of the dreamstate as far as I'm concerned.

Image courtesy of Huxley

Photo credit: Samuel Bradley

MILOSEVIC: I would love to talk about your upcoming tour and what you have planned for the show.

LEE OWENS: We actually get to create a world and build something where people step into a room, it's really gonna be Welcome to the Dreamstate. There's gonna be lots of spoken words and poems that open up the space. I'm really excited to present that world to people creating new visuals, it's still just gonna be me on stage. I still feel like that is where I'm at right now. I think playing with Depeche Mode gave me the confidence to continue to do that. It's gonna be very much a journey with those punctuations of emotive vulnerability, which I've never done before.

MILOSEVIC: I know that you started out working in a cancer treatment hospital. Do you think that your attraction to electronic music is tied to that in a way? I’m just thinking about transcendence in electronic music and the way that you describe it.

LEE OWENS: I used to think that it was so opposite to have done auxiliary nursing, working in cancer hospitals and also a nursing home before that. Being around death and medicine, and then I go and do music, people were like, “oh God, that's different.” When the pandemic happened, I was getting messaged by doctors and nurses saying how “Inner Song” was helping them through one of the most difficult times of their life. That was a full circle moment for me. What I loved about that job as auxiliary nurse was I could physically help people in the moment, it was an instant exchange of care. After my shift would end I’d sit there with patients who were dying, who had no one—I was 18 at the time. The more I've created music and just as a music fan, as a music lover, as an obsessor of music, I know what it does for people. You hope that your music can affect people in that way. It's not up to you to know if it does or not. Yoko Ono said something about doing good work and how it ripples eternally. It's not for you to determine how good it is or what it will do or not, but your job is to stay open and keep creating.