text by Agathe Pinard

photographs by Kealan Shilling

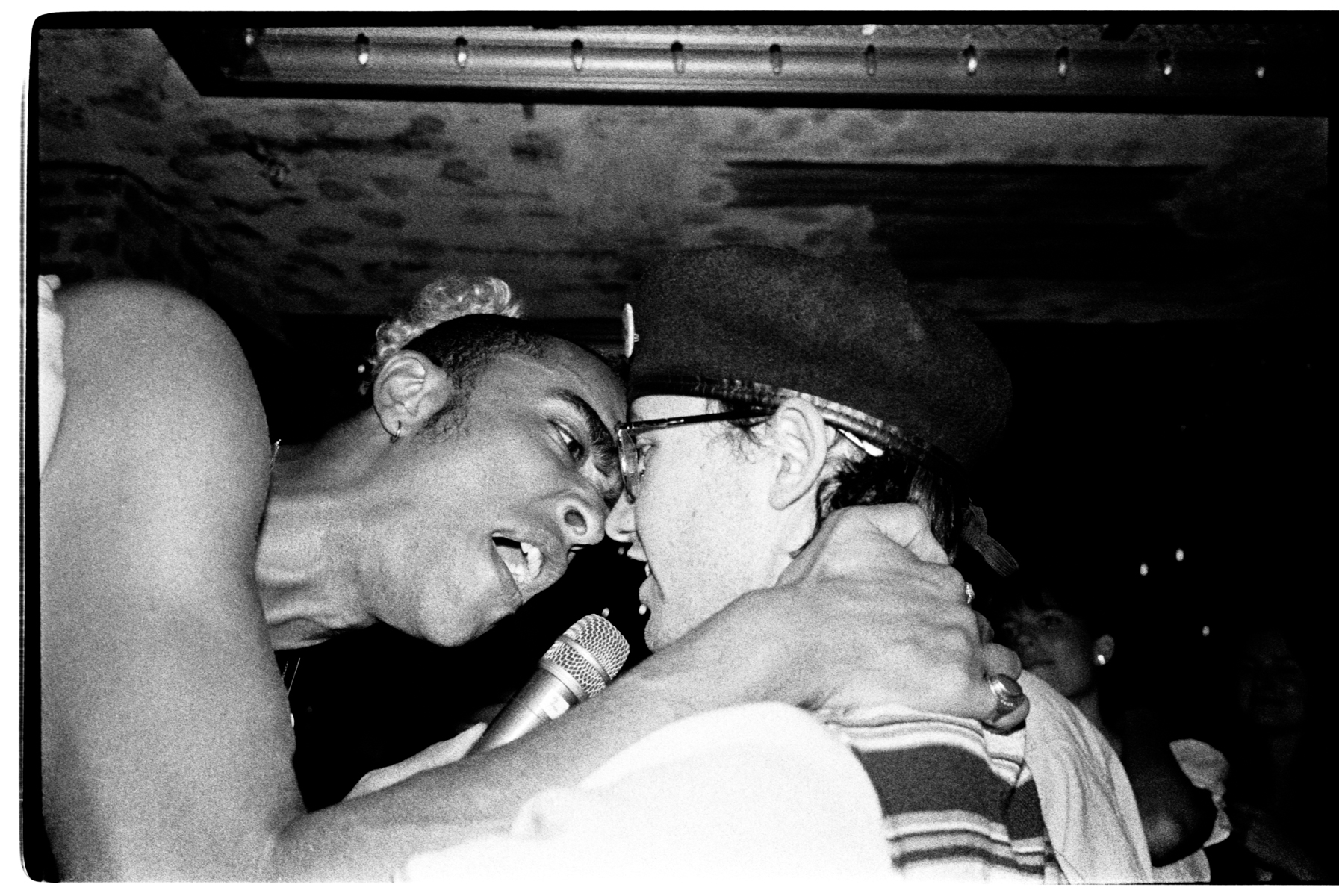

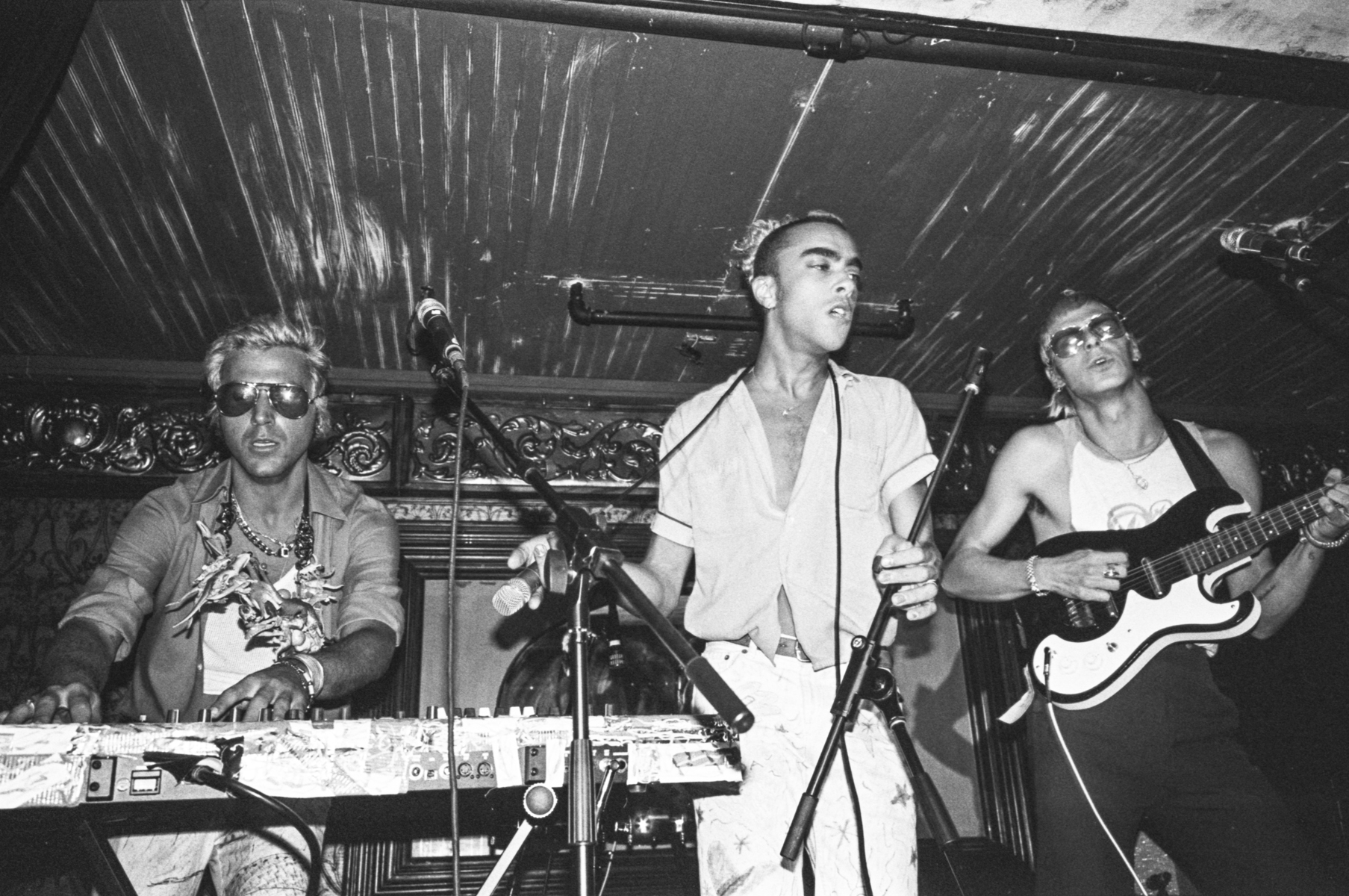

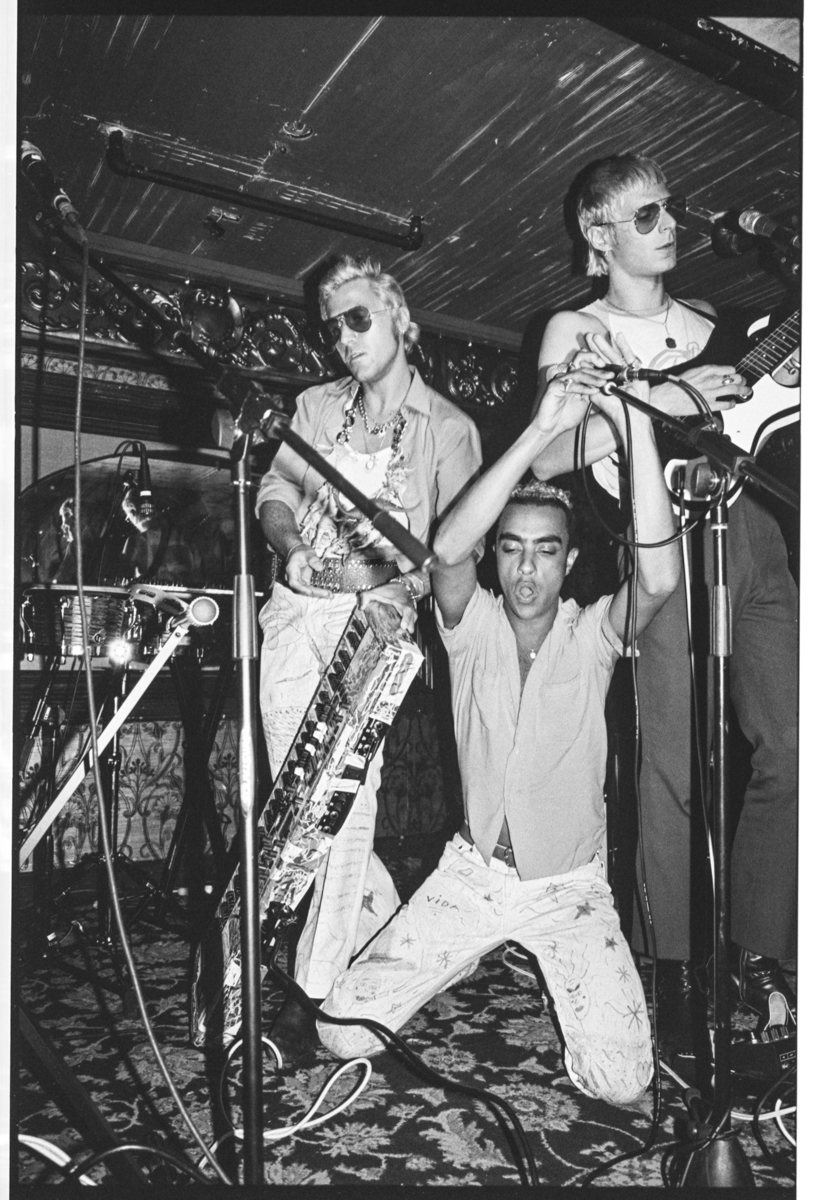

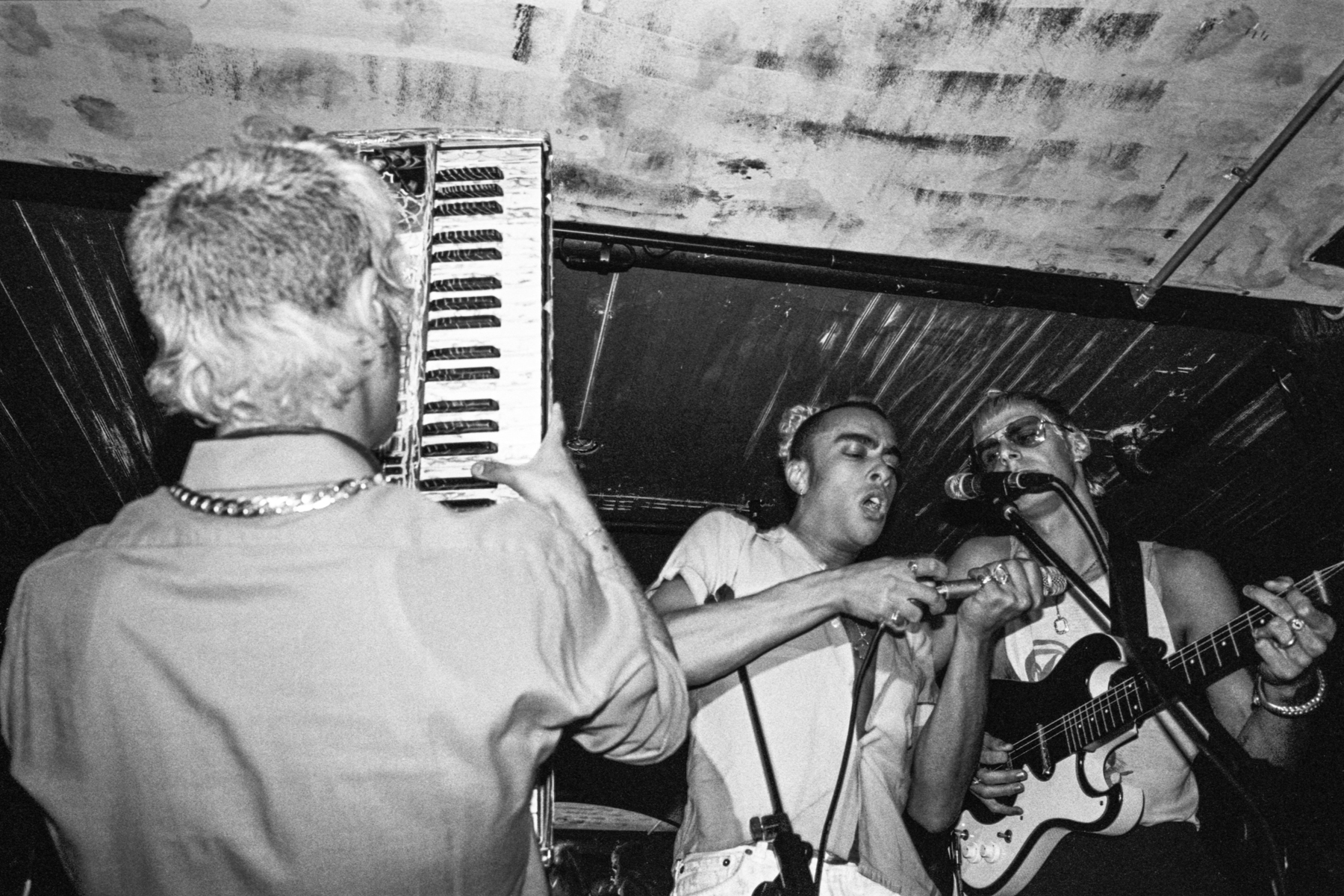

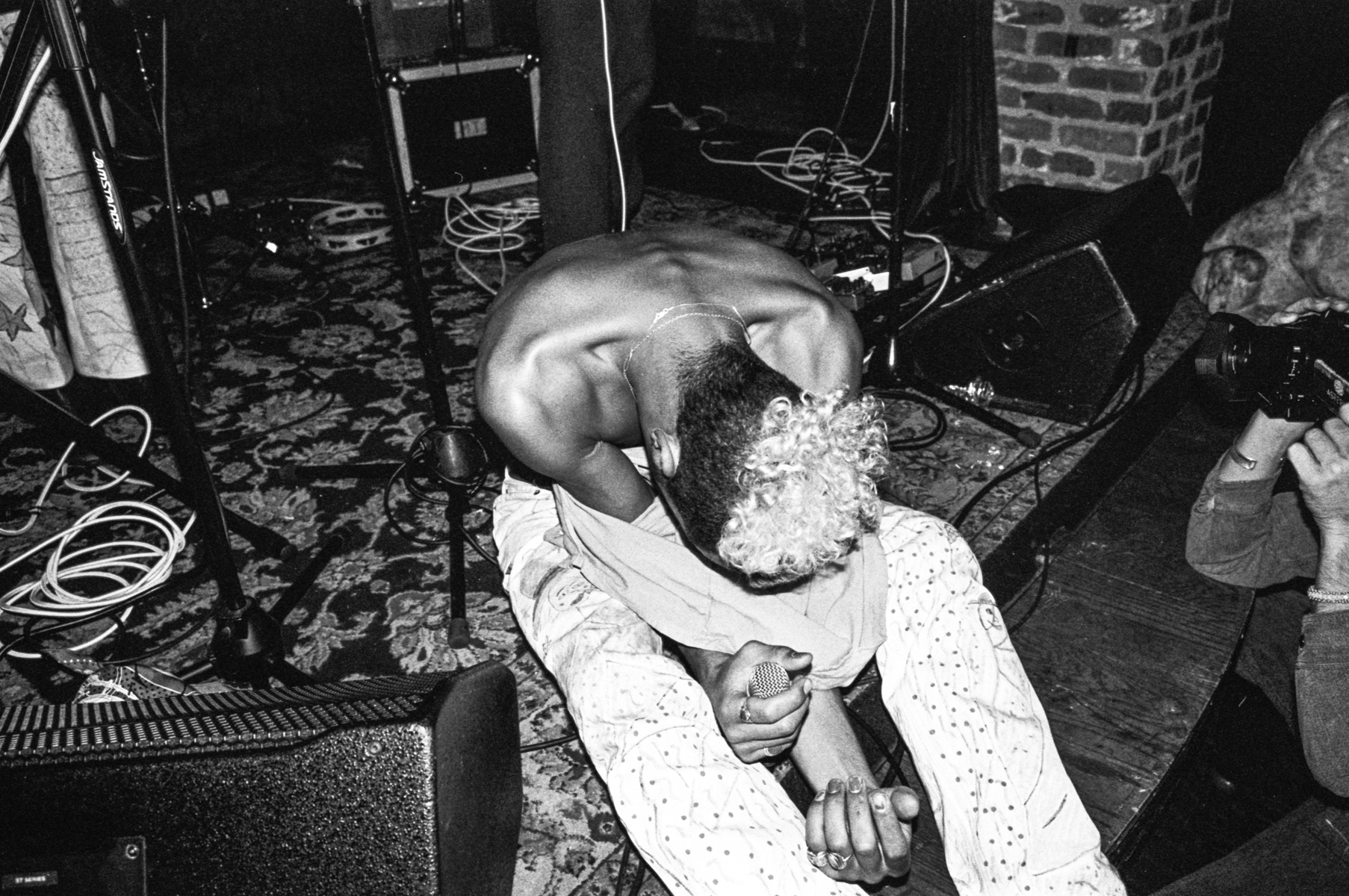

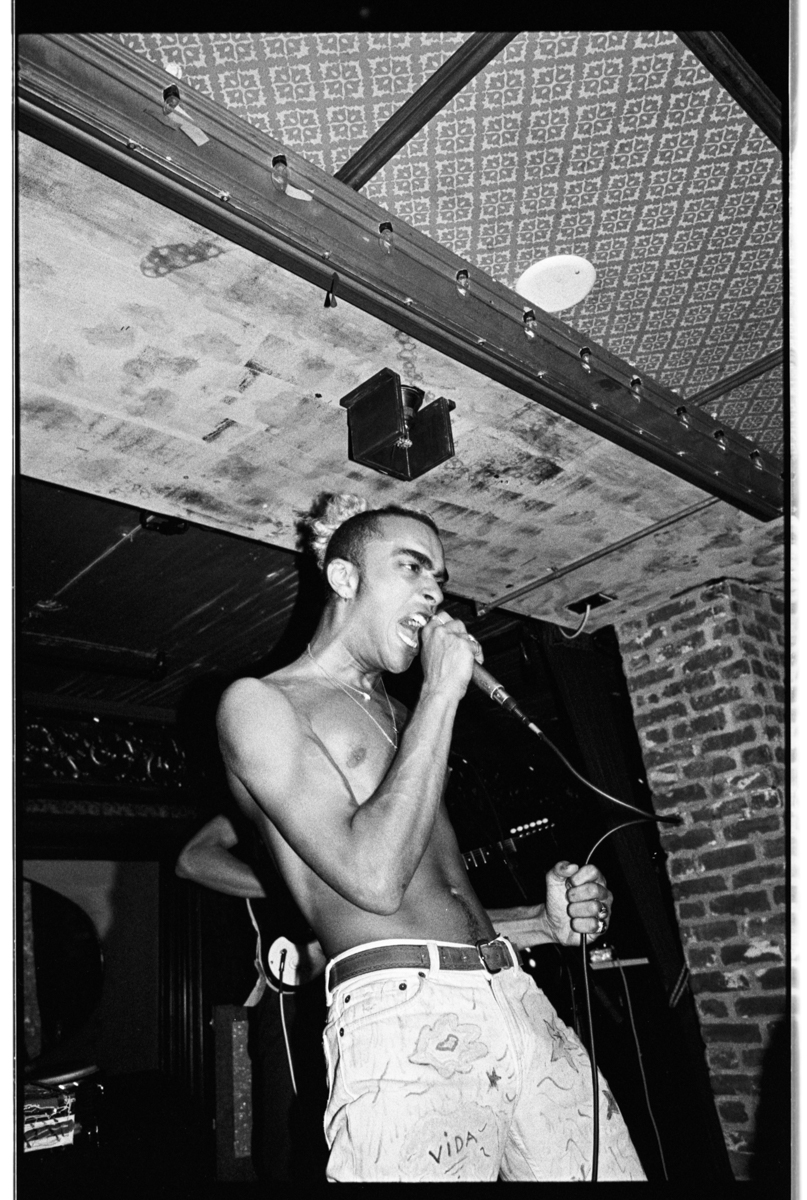

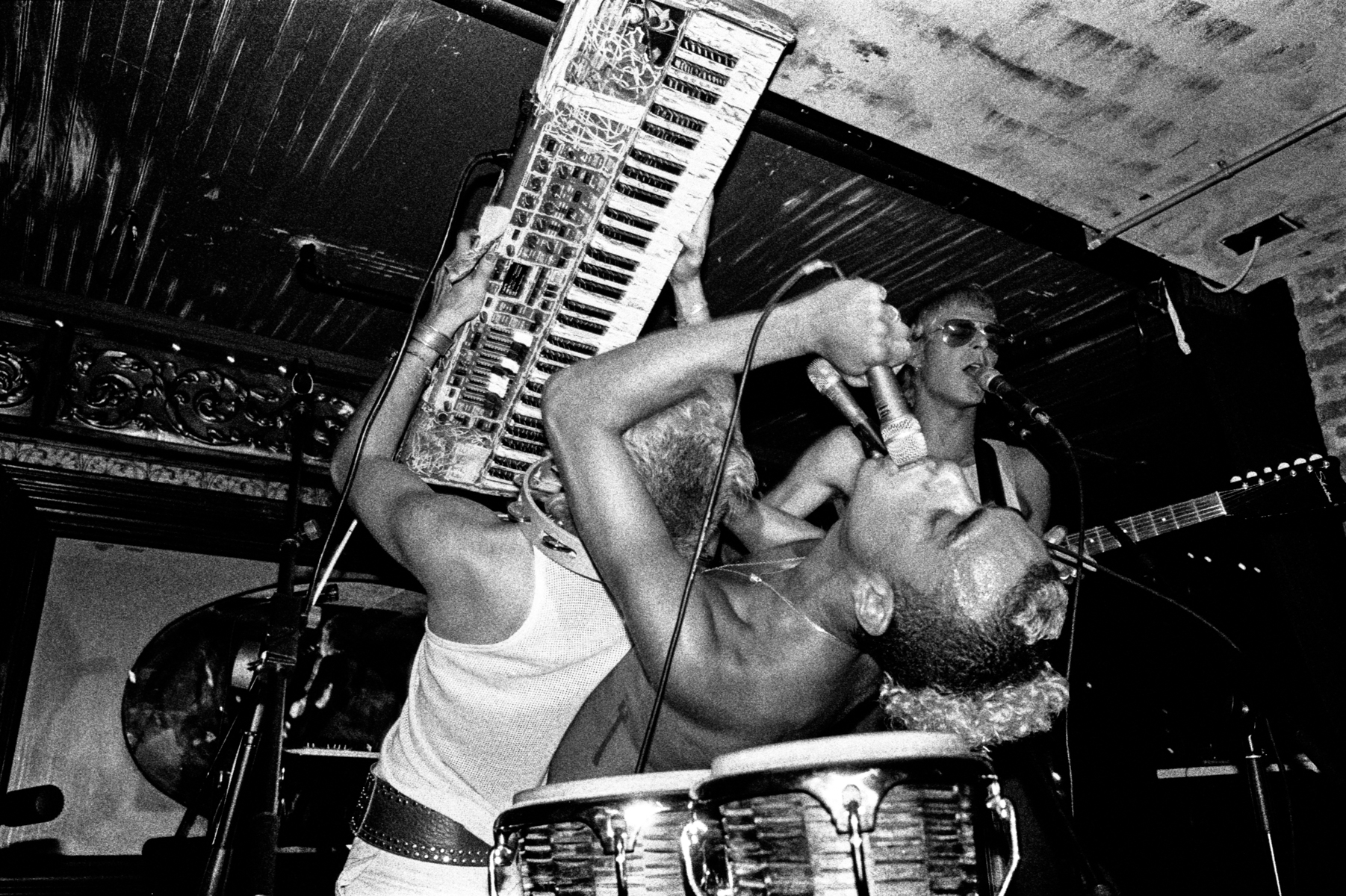

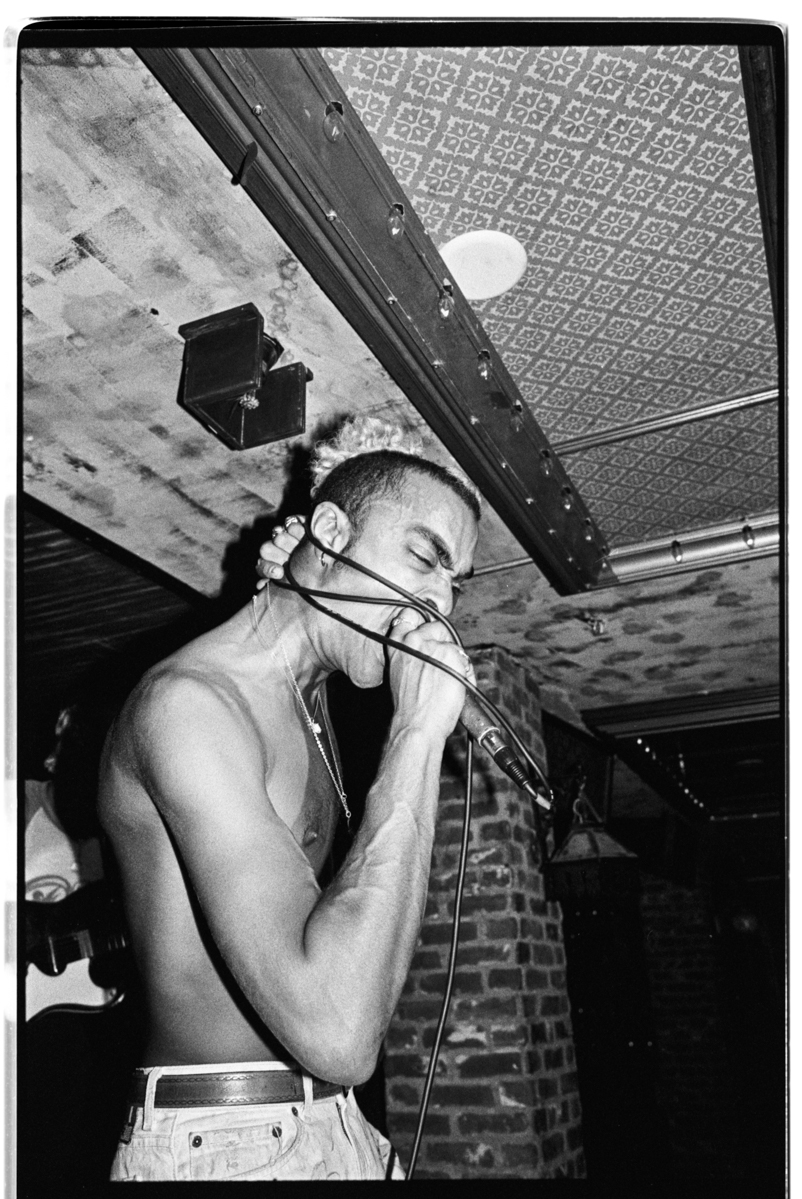

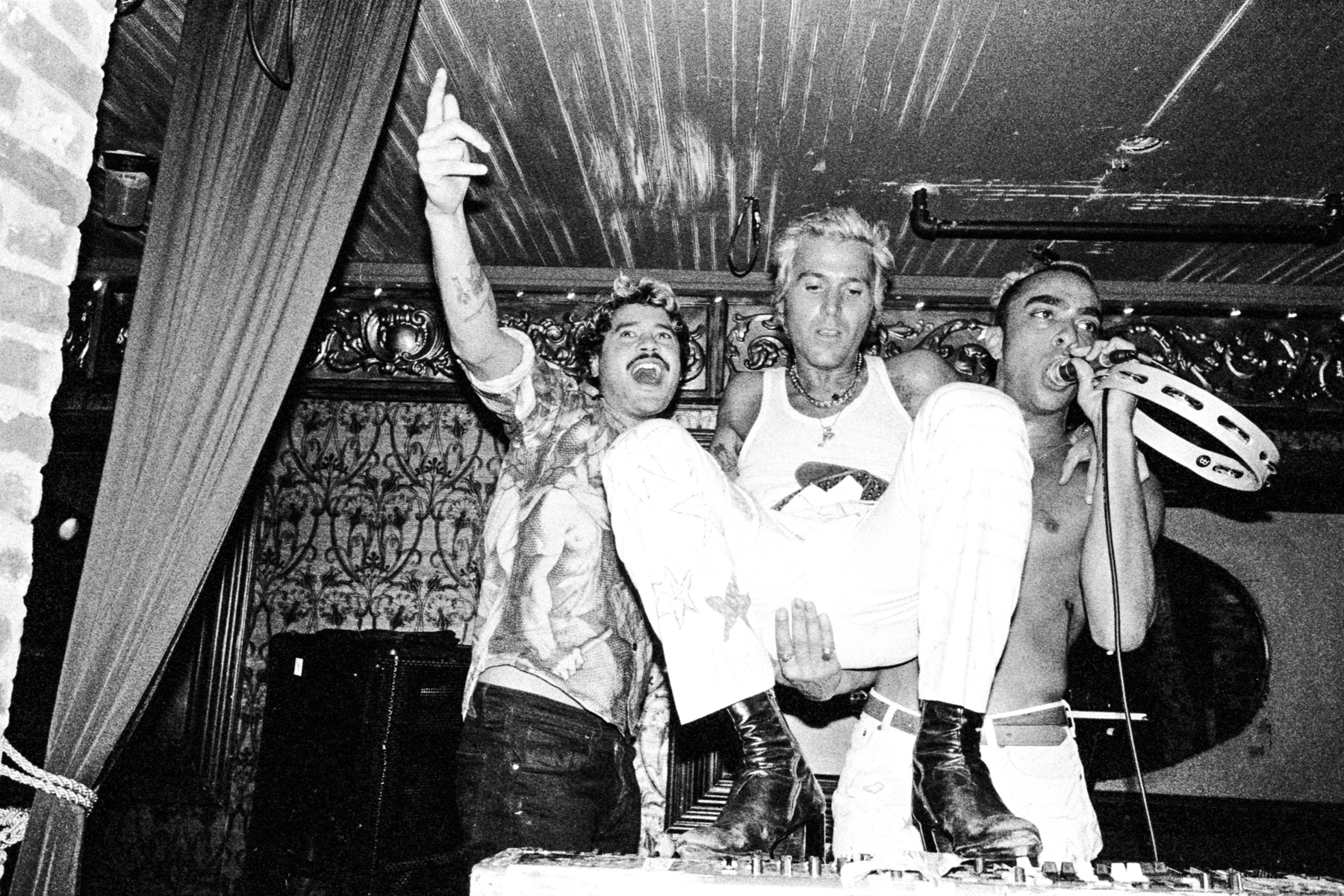

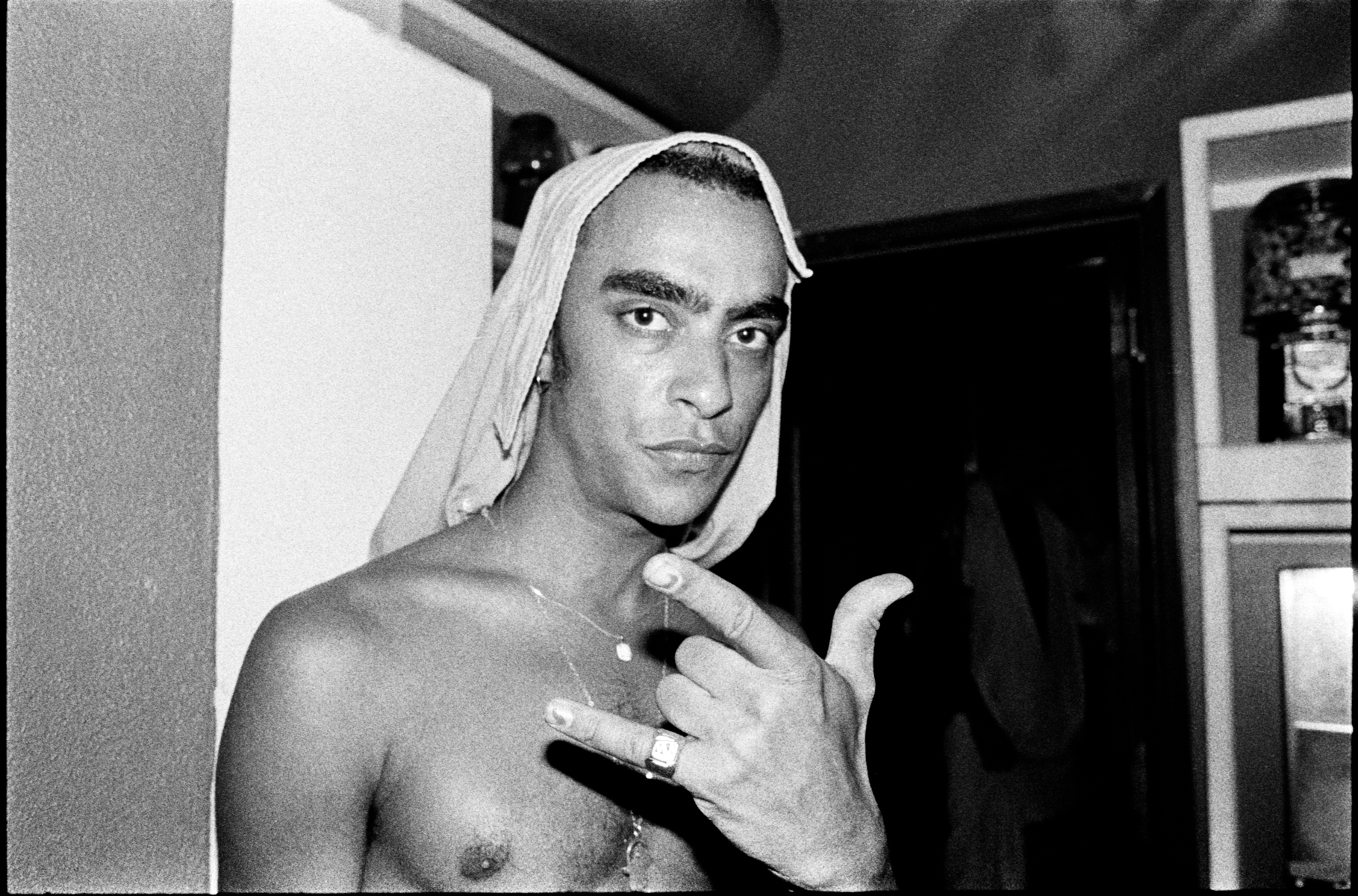

FAIRE are very serious about not taking themselves seriously. Their shows are infused with a raw improvisation that makes every performance a completely unique experience. They just play with the vibe given by the audience and then do their best to push the limits of that relationship. The images from their shows speak for themselves, filled with overflowing energy and rage. Romain, Raphael, and Simon make up the French trio Faire, a band emerging from the Parisian underground music scene. Self-labelled as “Gaule Wave,” the band mixes opposing sounds, from ‘80s synthesizers, to punk power chords, to the lyrical stylings of pop chanson.

We had a chance to chat with Faire just before their highly anticipated second show in Los Angeles. They play tonight at Madame Siam in Hollywood, catch them live at 10:00pm for a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

AGATHE PINARD: First of all, how did you all meet?

FAIRE: We met at school, we were about 12 years old. There we were, the only guys listening to rock, wearing leather and boots. So we easily found a subject of discussion.

PINARD: What’s your first experience with making music?

FAIRE: A basement in the center of Paris where we experimented with lots of anger, love, a few cries and lots of laughs. We took it very seriously, being musicians. We were rehearsing between class at least twice a week and started playing live shows pretty early on.

PINARD: Have any of you ever had any ambitions outside of music?

FAIRE: Not really, except the fact that we love to customize/make clothes, and making videos, drawing, painting and writing.

PINARD: What’s the meaning behind the name Faire? Did you have any other names you were also considering?

FAIRE: First we thought about “la GAULE” which is the old name for France and it also means to have a boner. It ended up becoming the name of our music: “Gaule Wave.” But we wanted to explore a maximum of different musical horizons. We thought that with FAIRE (meaning “to make” or “to do”), we could mix all kinds of music that we like, surfing between rock, yéyé, Eastern music, trap, techno and more. Also it’s a simple way for us to make music without thinking too much, and just go with the flow of our spontaneous ideas, like a manifestation of sorts.

PINARD: Do you have any major musical influences?

FAIRE: Yes! We started playing music together while listening to Led Zeppelin, Steppenwolf… and the Motown Records really inspired us when we were younger. Later we let go of the stigma that we had of drum machines and were really inspired by ‘80’s cold wave, and especially Martin Rev of Suicide. French Pop culture influences us too, think Michel Polnareff, or all the old ‘50s songs with those incredible lyrics. Swinging by the US, people like R. Stevie Moore just transcend us. But for real, the list is really long, we’re not even talking about all the African, Indian or South American influences!

PINARD: Are there any non-musicians who inspire your work?

FAIRE: We met the incredible Charlie Le Mindu, the French hair designer who also does exhibitions of clothes made with an infinity of hair. His work is absolutely amazing.

PINARD: What’s your personal process of creating an album like?

FAIRE: We like to be really isolated in a countryside or on a rooftop in Mexico, as we did with “Le Tamale.” Notice that we never really put out any albums, it was only EPs that we self recorded in our computer. Now we are preparing the recording of our first album, which we want to record live with someone capable to catch our live energy, because that’s where our potency lies.

PINARD: You seem to like using old women’s names as titles, Mireille, Sisi, Christiane, Marie-Louise, is there any particular reason?

FAIRE: We just love our grandmother’s stories and the era that they lived.

PINARD: You released a very psychedelic video clip of Noizette a month ago, what’s the story behind it?

FAIRE: Some student from l’ECAL, an art school in Switzerland, asked for a song to do a video clip, then pitched the idea and we liked it! For the first time we just let them do what they wanted and received 6 different versions. We had the luxury of choosing the one we thought was the best. This battle between our faces and the Prince was exactly the kind of trip we liked.

PINARD: Is there a show you gave that you will remember forever?

FAIRE: Wow, when we released our EP « Le Tamale » in a Parisian bar people were so excited, and it was so overcrowded that the public was making waves falling down every two minutes on the little three-by-three-meter stage that they kept us from playing long. All our machines got disconnected and fucked up at the same time (it was also because of some spilled beer.) And we had 20 kilos of confetti flying around everywhere. It was two years ago, but we still have some in our synthesizers. It was definitely the best show/non-show.

PINARD: You’re all super wild and insanely energetic on stage, how do your rehearsals differ from your live performances?

FAIRE: (Laugh) that’s a good question. We take it really easy and chill, the exact opposite of our live shows.

PINARD: How do your audiences affect the performances?

FAIRE: We started being crazy on stage after some shows in Mexico where people were getting totally crazy, and thanks to them we took that energy, and it morphed us into these uncontrollable beasts. Now even if the crowd is really chill we get into them with all our passion and love, and push them to dance by jumping into the pit.

PINARD: What was it like to play in LA for the first time?

FAIRE: Really great, people were really into the fact that we got the mosh pits going. They weren’t accustomed to it or prepared for it at all. So we were kind of exotic with our craziness.

PINARD: How was your experience with the city of LA, the American culture?

FAIRE: Pretty interesting, lots of cool vibes and a beautiful mix of various world cultures over there. People were lovely with us, and we met great artists there. Also Simon’s dad is from LA so we had a good introduction to the city.

PINARD: It’s been more than a year since the release of your last EP, C’est L’été, what are you working on at the moment? You said there is a new album in the making?

FAIRE: Absolutely, we are now preparing new songs to record our first album. It will be released next year, but the date is still a secret.

PINARD: What are you listening to right now? What was your summer ’18 soundtrack?

FAIRE: Escape-isms, HMLTD, Lil Pump and les Charlots.

Go see Faire play tonight at 10pm @ Madame Siam in Hollywood. You won’t regret it!