Text by Adam Lehrer

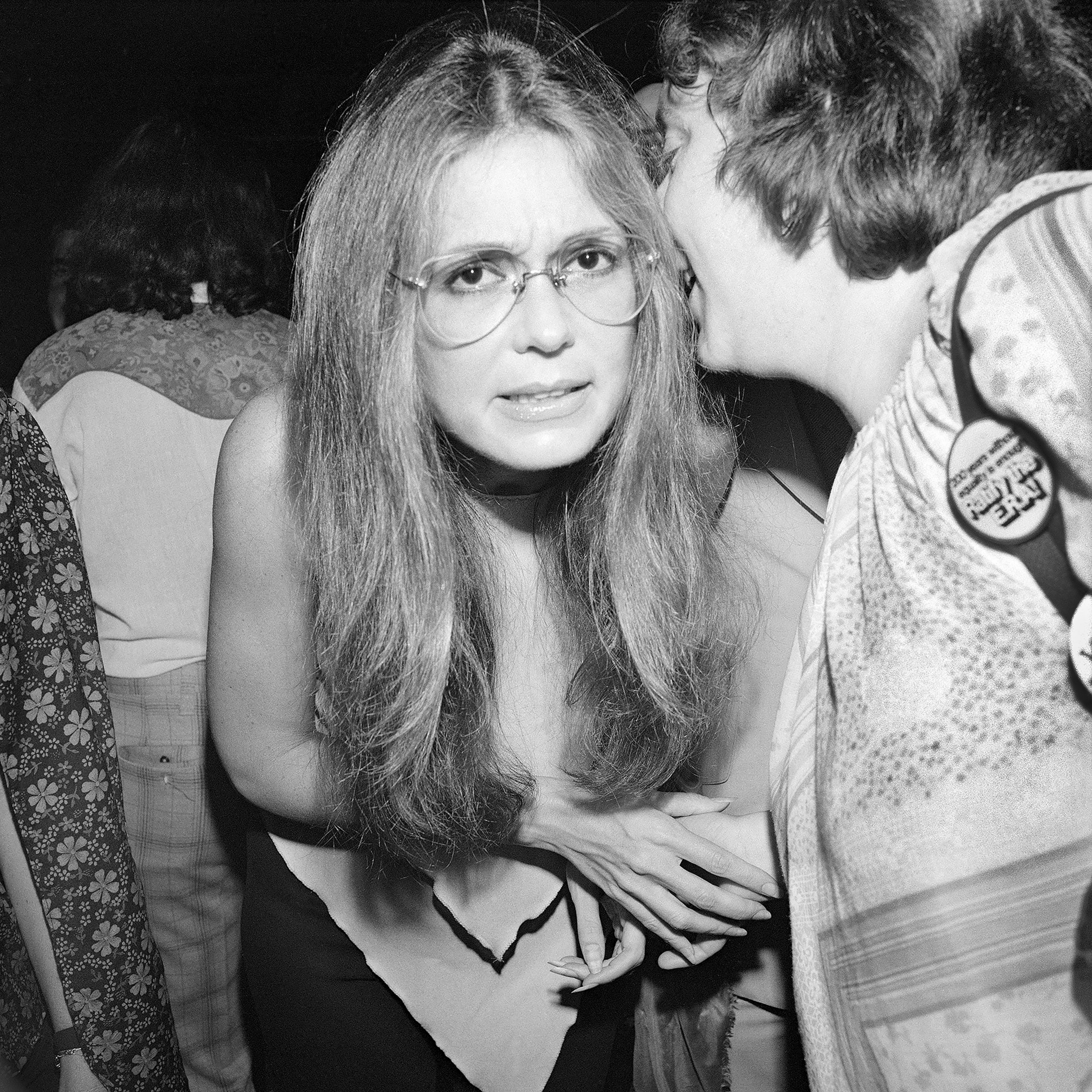

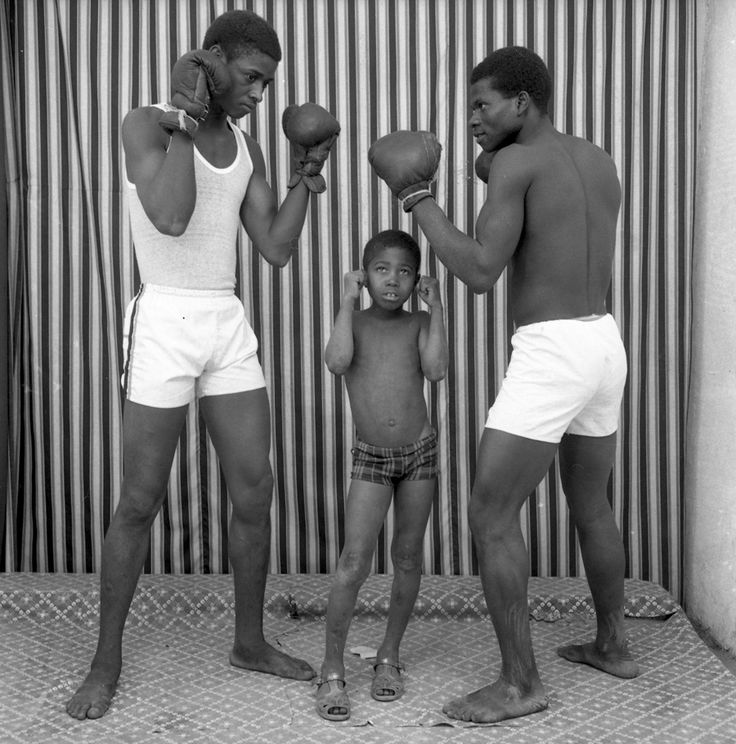

Photographs by Meryl Meisler courtesy of Steven Kasher Gallery

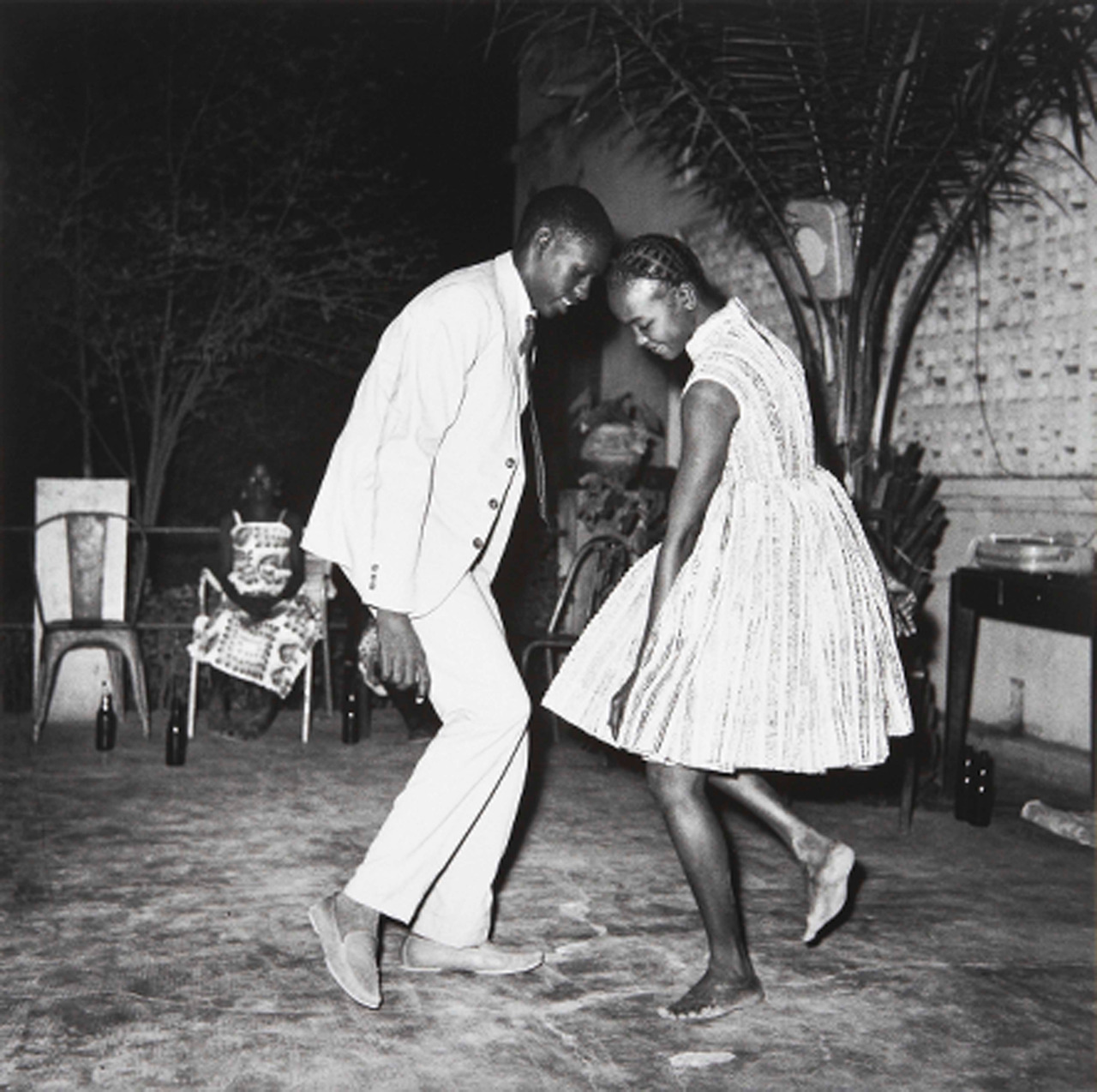

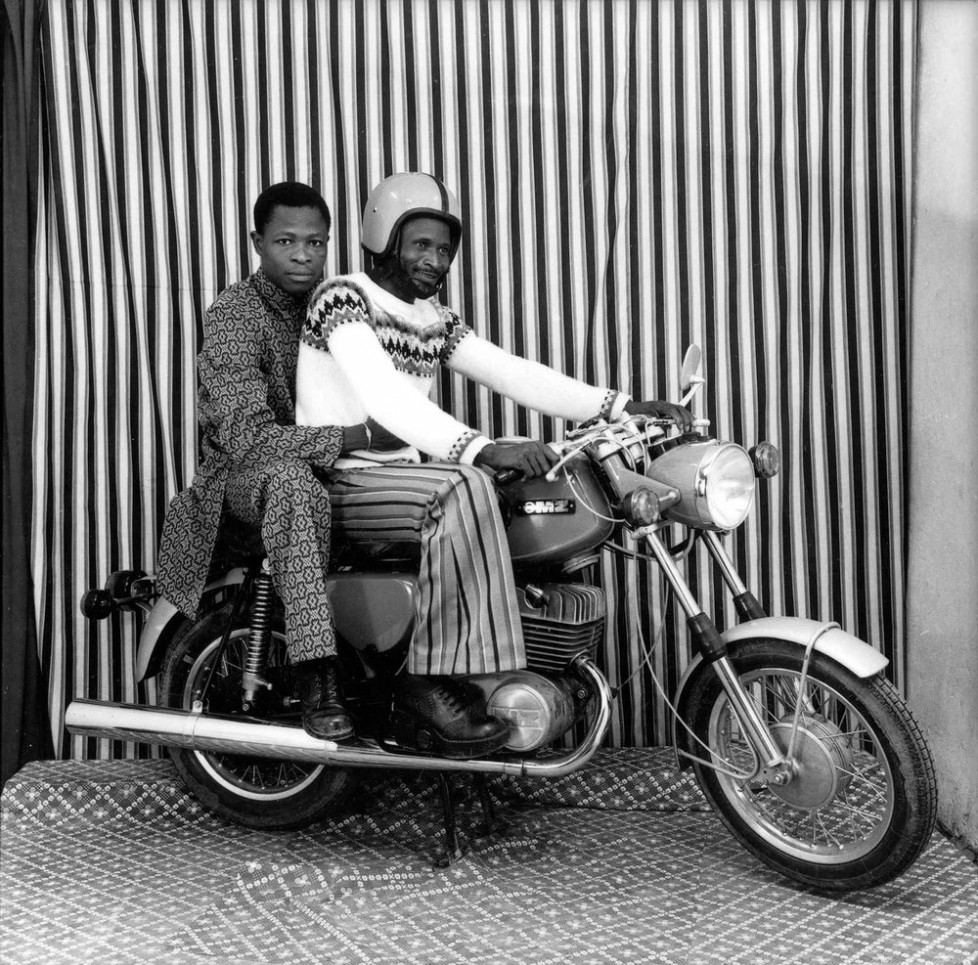

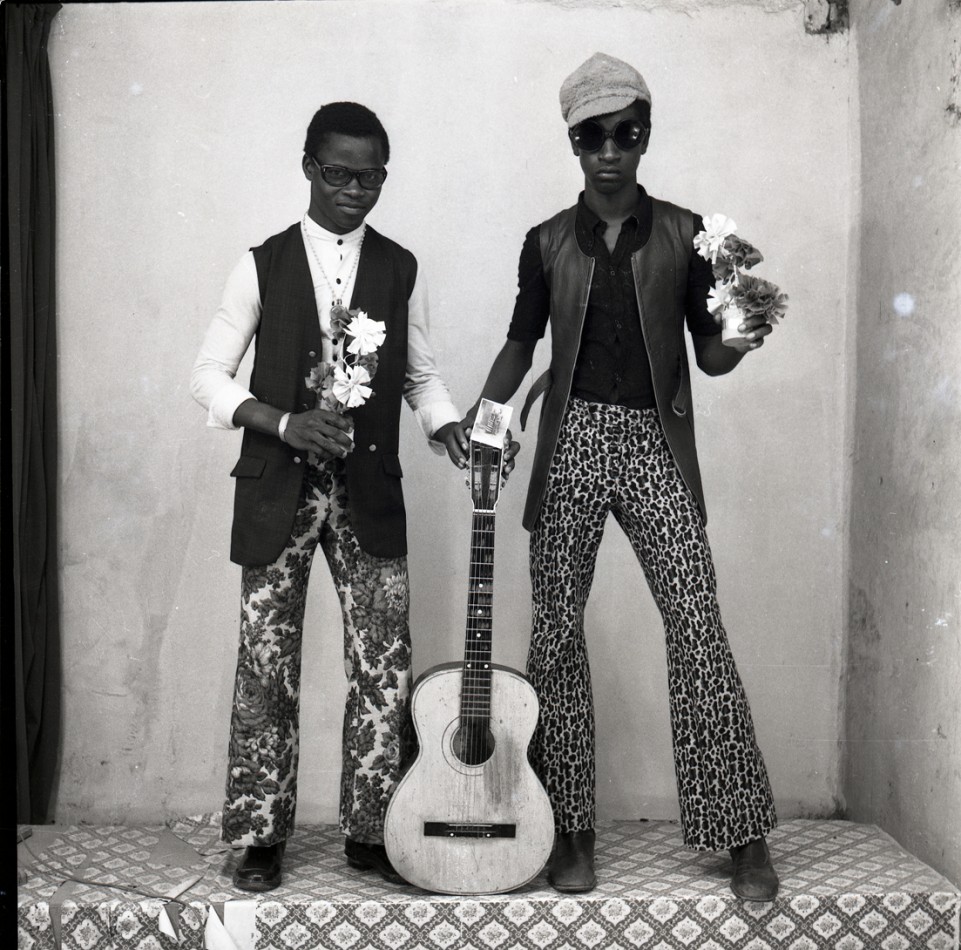

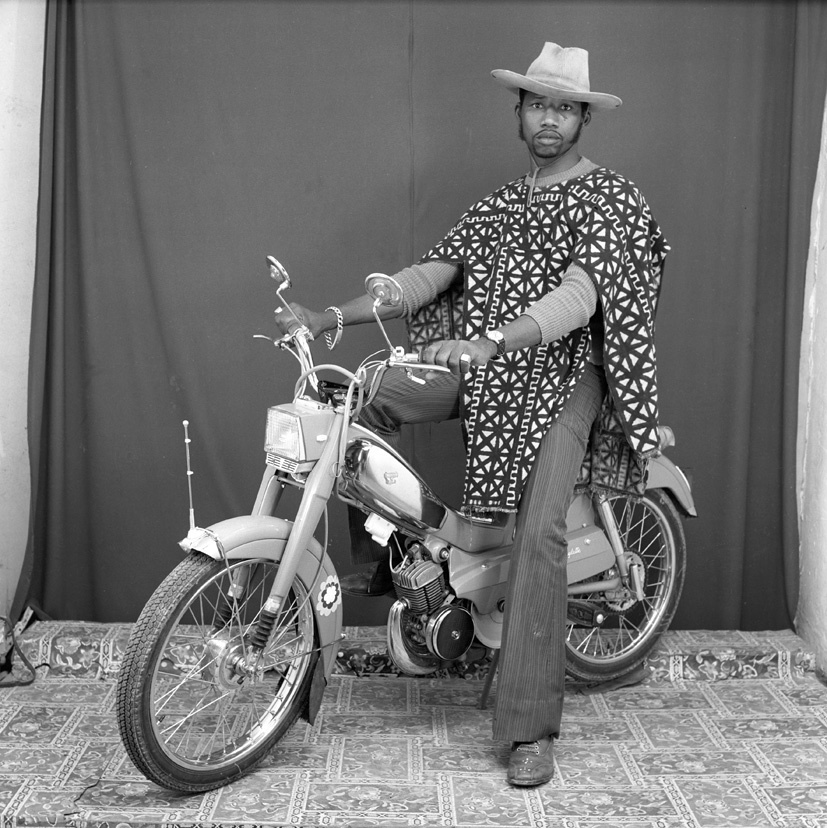

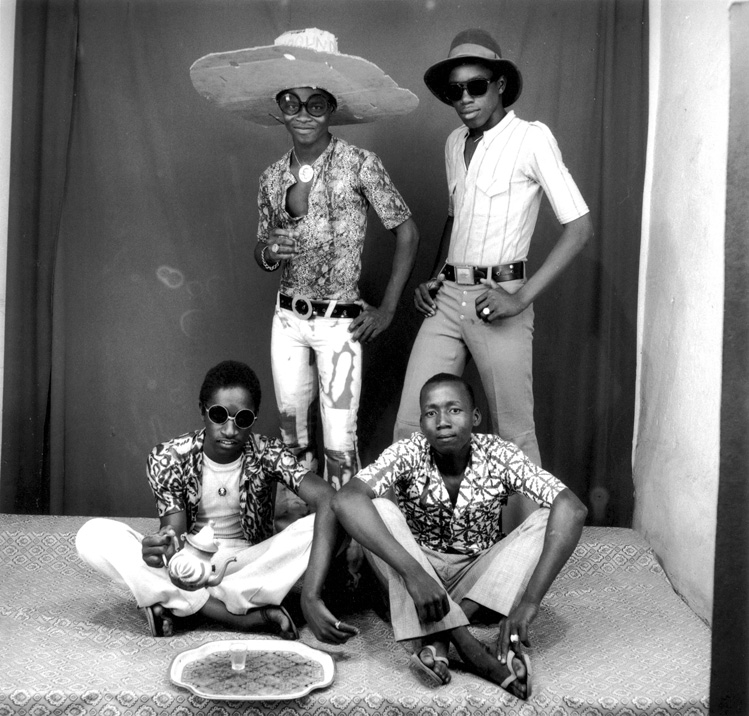

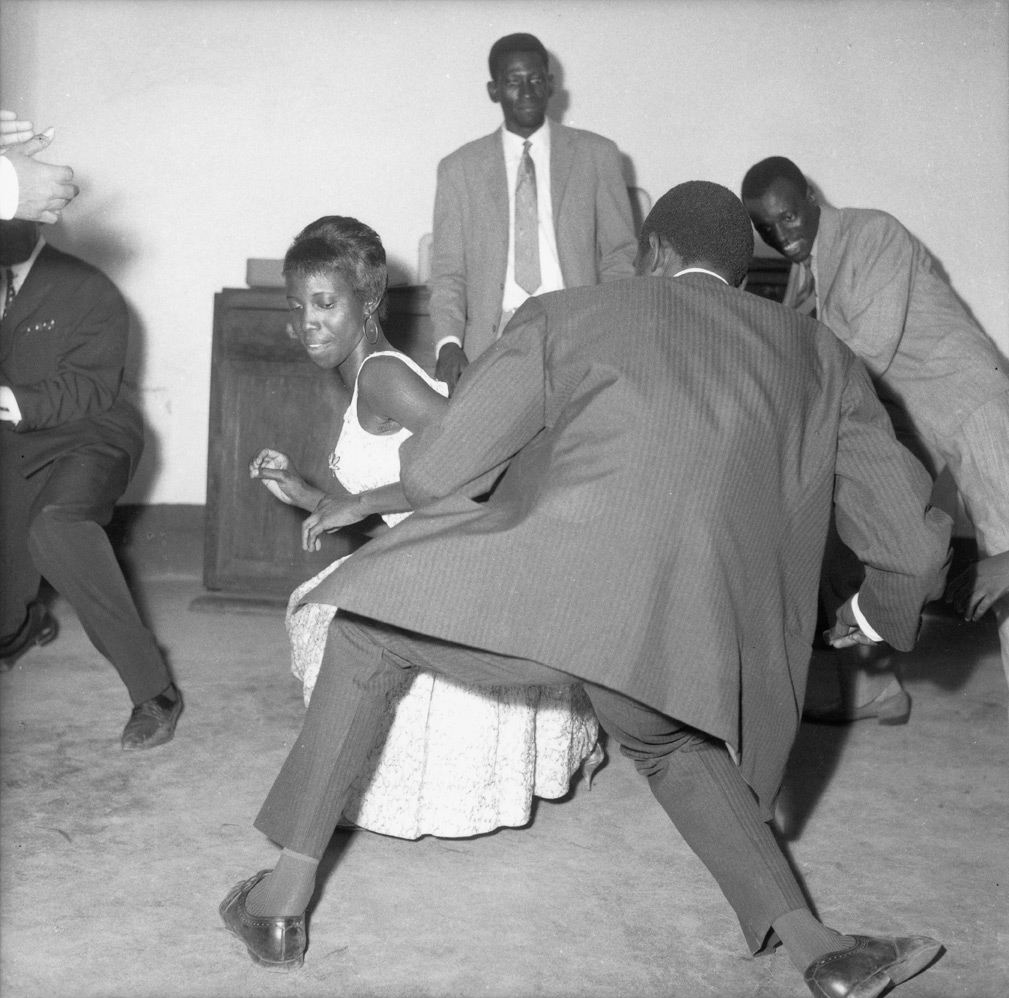

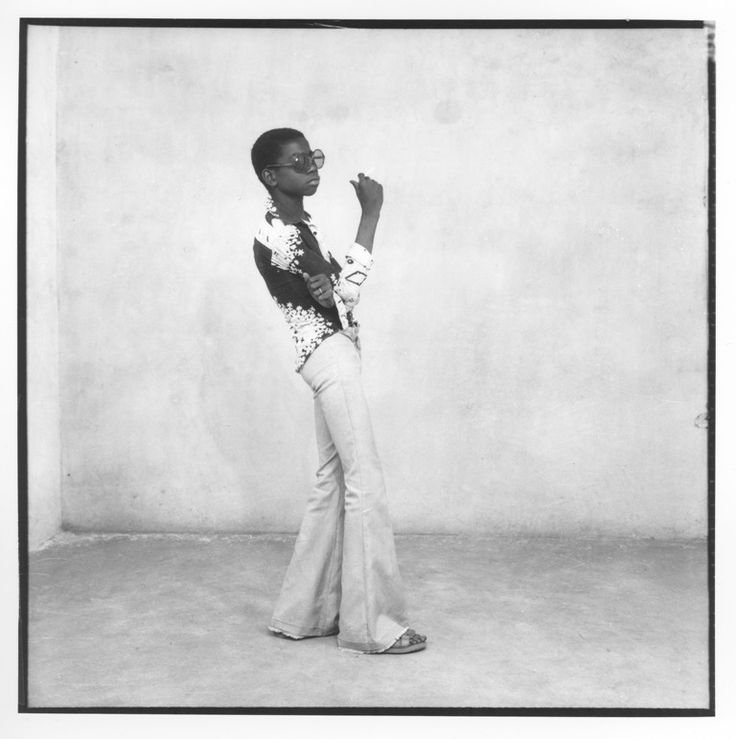

What lifts the medium of photography into the realm of fine art is contrast. During the 1970s, Meryl Meisler was a teacher by day and a disco dancing queen by night. She photographed everyday life in Bushwick, and she documented the wild scenes of the discos. In her work you find sobering scenes from an impoverished and crime-ridden city, and yet its inhabitants can be found each night celebrating their fundamental rights. The right to don a more perfect look each night, the right to be a free sexual agent, and the right to dance. Her recent book, A Tale of Two Cities, depicts the stark contrast between the aching realities of life in Bushwick and the opulence of a nightclubbing scene that the artist describes as her Versailles. In these photographs, she channels humanity’s ability to rise above the chaos and revel in the miracle of life. I spoke with Meisler on a balmy day in New York to talk about the state of the city in the 1970s and the sanctuary that was the disco scene.

ADAM LEHRER: I know your grandfather and your father were both photographers. Was that your initial exposure to the form?

MERYL MEISLER: They were a tremendous influence: their styles and purposes and just that they did it. My dad did mostly family portraits. I have his negatives and large prints. You can see pictures of his brothers, pictures of when he was in the Coast Guard, self-portraits of him writing letters, photos of when he was dating my mother. They were just really beautiful black and white portraits.

Were you already looking at photography as fine art while you were in art school?

I did not, but I saw purpose in it. My last year of undergraduate school I came home and went to see the Diane Arbus show at MoMA. That was the first time I ever saw photography as art. All the Arbus classics staring at me. I was moved. I took a class with one professor in college and he introduced us to documentary photographers and Henri Lartigue. My mindset became “this is art.”

I can see some of the influences in your work because it had some of the poetry of Arbus, but also Lartigue’s glamour. Did you think of the disco as your Paris or your ‘place of action?’

I thought, “This is my Versailles.” I knew disco was a scene that was wild and interesting. But those places were full of photographers so I never showed these photographs. When I did, I was pleased that people found a uniqueness within them. I always felt I had a special eye. I saw things differently. Even as a kid, I would look up at trees and say to friends, “aren’t they the funniest trees?” I capture a certain energy.

Absolutely.

When I was in graduate school, I went to go see a psychic who could read spiritual things in photographs. Looking at a photo of my grandfather, she said something terrible happened with this person. My grandfather took his own life. I think that photographs have a spirituality.

What I really love about your photographs is how well the Bushwick and Disco photos juxtapose each other. New York at that point was in ruins, crack was at its worst, and Bushwick was crime-ridden, but you found joyous moments. Was that intentional? To paraphrase Keith Richards discussing ‘Exile on Main Street,’ were people partying in the face of tragedy?

I realize now I was taking pictures of things I found uplifting because I couldn’t afford to quit teaching. Bushwick was tough. But I also found it to be friendly and warm. Whereas the disco stuff, I wanted to go deeper. There were darker things on the disco scene. As dark as Meryl gets.

What did you prefer about disco, as opposed to punk rock?

I liked the big club, I liked the lights, I liked the fashion, the bathrooms certainly were a lot cleaner, you could dance. I went to CBGBs, but disco was my scene.

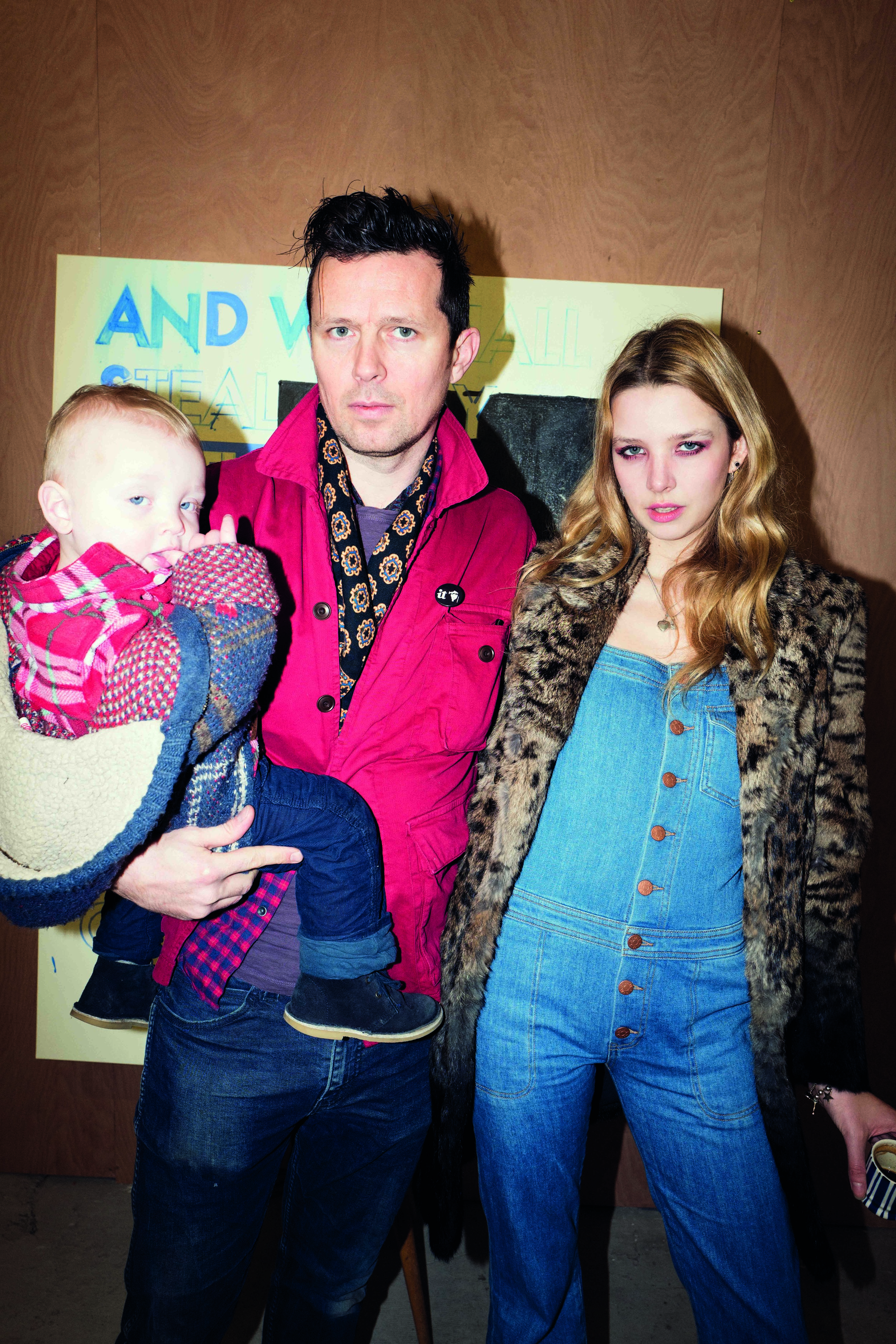

How did this reappraisal of your work at the Bushwick bar, Bizarre, come into fruition?

During Bushwick Open Studios one year I went to get lunch and Bizarre bar owner Jean-Stephane Sauvaire says, “Hello, this is my place!” and he showed me what he was doing there. They didn’t even have a food license yet. And then he showed me the basement that he painted dark and he said, “I’d like to show photographers like you here.” I told him, “I’ve shown in museums and now I’m gonna show in the basement of a bar where they’re stealing stuff off the walls!” and he says, “don’t be such a snob.”

That’s how you introduce it to a new viewership.

He said, “I want to publish a book.” I’m thinking this guy is out of his mind. I’m thinking okay, “I want it to be about Bushwick and my disco work, these worlds connect.” He asked to see them and I just started scanning them. My spouse Patricia Jean O’Brien designed the book and we put it together. Bizarre became my publisher, which is the most bizarre thing.