GRAHAM: Wow. So you had no idea what they looked like until you printed them up?

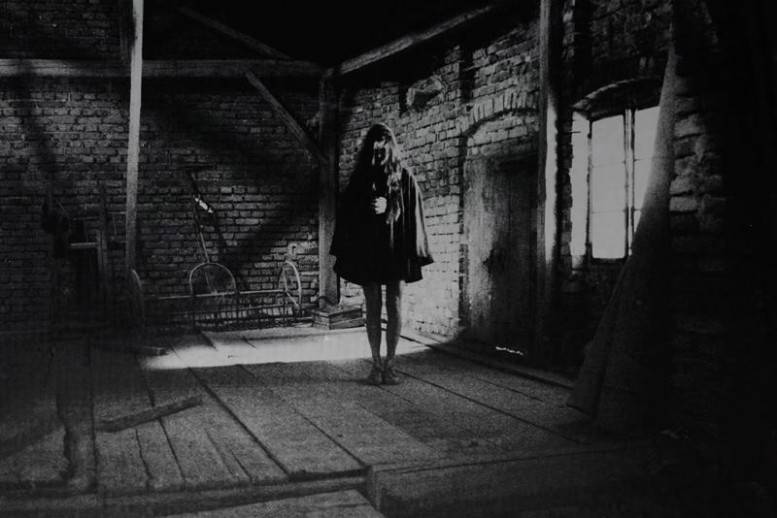

BURKHART: I knew what they looked like, but not this big… and all the ones that were shot on film had to be meticulously cleaned, because they were full of dust and scratches… and then I started shooting digitally, and, you know, that took care of that. But the odd thing is that now, all of that’s online and there are fewer and fewer porno shops… they’re being overtaken by young clothing designers and stuff. The whole neighborhood’s being gentrified; people buy this stuff online now. So a whole visual culture is disappearing. Something that was at first kind of documenting my reaction to this, what seemed to be openness, but is really just commerce… started out that way, and then I realized, wow, I’m kind of documenting a moment in history that is going to disappear eventually as everything goes online. And now it looks like this. [Gestures towards a photograph of a “tasteful” window display in an Amsterdam sex shop] That was taken this summer, in that neighborhood.

GRAHAM: It looks like an installation piece, almost.

BURKHART: Doesn’t it? I know. Here we have your tasteful tit and ass prosthesis for rich trannies, or something. It’s got that… I mean, it’s still the surrealistic kind of mash-up, but it’s all… everything costs more. I’m going for a residency this summer at the Center for Contemporary Art in Majorca, so I’m going to shoot a ton more of these nudes. I’m going to be a photo machine. I am a camera.

[We go back into the painting studio through a secret passageway]

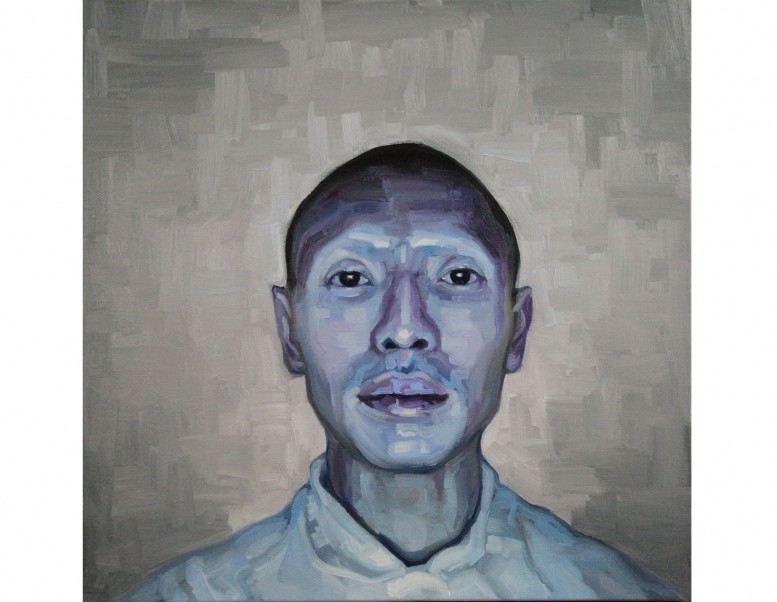

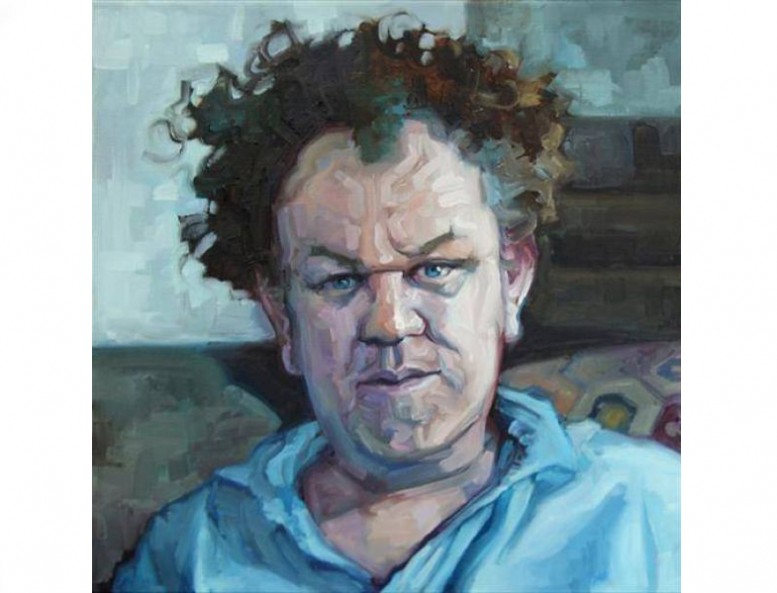

BURKHART: [Gesturing towards one of the Liz paintings involving a voodoo doll and pins] And this one has pins… Many many pins. You can really see how many if you look back here.

GRAHAM: Wow. Guess you have to handle that one with care. So… what’s your reaction to the perception of you as a “bad girl” artist?

BURKHART: Well, it really morphed into something that I didn’t intend very quickly. We didn’t have words like “gender nonconforming” when I was your age. You were gay or straight, or you didn’t exist, basically. Now, fortunately, we have that word, gender nonconforming, which encompasses sort of what I meant by being a “bad girl.” It was picked up and marketed… it was strange, it was like suddenly to be a bad girl was to be a lesbian. I didn’t get that, I mean, there are plenty of “good girl” lesbians. So, I wanted to represent a kind of woman who wasn’t represented, who wasn’t complicit, who was a noncompliant subject… and that’s what I meant by it, more or less. Gender nonconforming, a noncompliant subject with agency… Liz Taylor’s a good container for me to dump all that personal history into, because she’s unashamed about having appetites… for sex, for food, for money… for all of the material things that we associate… with hedonism, really. So, in a sense, it was like an unapologetic hedonist, and a linking-up of a punk sort of resistance. It wasn’t about cowgirls, or lesbian mothers, or any of that… What happened was, I was on the cover of Flash Art, the article was called “Bad Girl Made Good,” it’s the first time that term was used in contemporary art. But then it was picked up on by the media and applied to artists like Lisa Yuskavage, Tracy Emin, etc...people who really wanted to be…'good'. So some women who basically wanted to be part of the tide seized upon the “bad girl” mantle, which also for me encompassed a bit of performativity; that the work would come out of the life, and for that to work, the life had to be interesting. So it was all of those things and more, but it quickly spiraled out of control when the Bad Girl shows happened. So it was considered stupid… Laura Cottingham wrote an article called “How Many Bad Girls Does it Take to Screw In a Lightbulb?” and… it really spiraled out of control and became totally negative, of course. I mean, you say “bad boy” and people just snicker. Soon it became kind of feminist infighting. Like, “I’m not a bad girl, that’s stupid, whatever, I’m a prisspot intellectual. I’m neuter.” [LAUGHS]

GRAHAM: Can you really be “neuter” as an artist?

BURKHART: There is that kind of position. There’s a neuter position, women who are not attractive and so they can’t factor their sexuality into it, because they don’t have it, so they’re not threatening. So, when you’re a young woman you can have a lot of success with your sexuality up until you’re about 35 and you have power. So then it’s like, you have a little bit of power and you’re sexual and good looking and smart? That’s really fucking scary. So they put you out to pasture until you’re like 50, and don’t pay any attention to you. That’s how it is. Because they’re figuring that you’re going to breed and leave the field. And if you don’t breed and leave the field, or if you breed and make money anyway, after you’re about 50 and you’re not dead yet, then they can… then you’re harvestable.

GRAHAM: So it’s a bleak future.

BURKHART: I’m sorry.