text by Barbara Norton

"Hymn of love. Cannibalism. Communion.

Jean - I devour you. I absorb your strength. Your soul joins mine.

Breakdown, movement, now belong to me too.

Waiting for the breakdown, waiting for Godot, waiting for the mishap, life.

I am even looking forward to the breakdown (perhaps to experience the infinite joy of things working again).

Through my new works, Jean, we continue to collaborate. You are present even if these paintings don't look like you.

ORDER. CHAOS. CONCRETE. ABSTRACT. COMPOSITION. DECOMPOSITION. ETERNAL RETURN.

These ideas took shape in my mind through intuition.

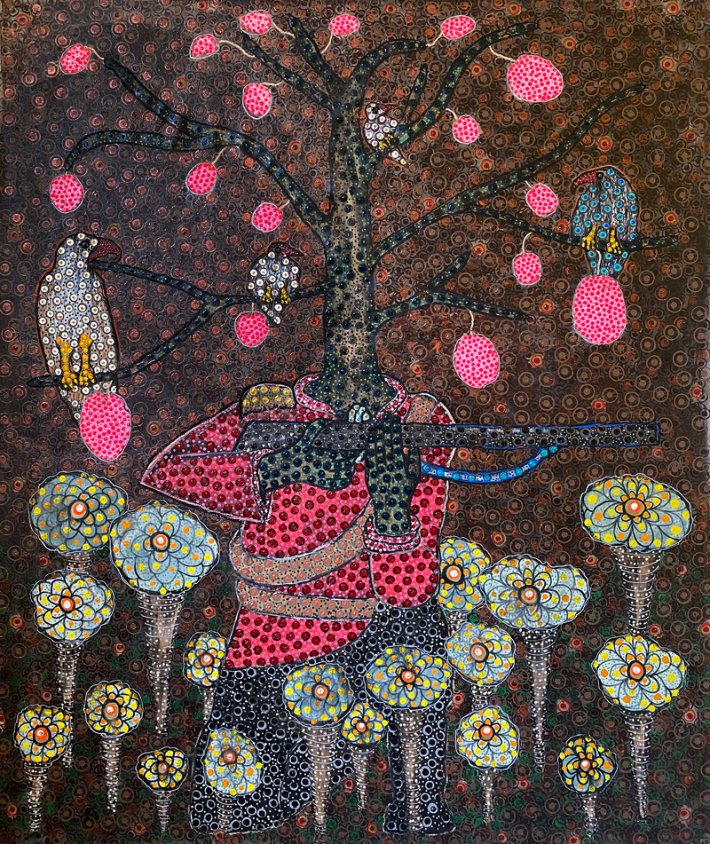

My first subject was Hindu deity Ganesh, bearer of luck and happiness.

The 'tableaux éclatants' have become my pals, my companions.

A photoelectric cell activates them, so someone walking by is enough to animate them.

If I go down in the middle of the night to eat a banana, I am accompanied by a light show, sound, movements and soft noises.

I have taken down all my older paintings and live only with them."

Niki de Saint Phalle, Letter to Jean Tinguely, 1993

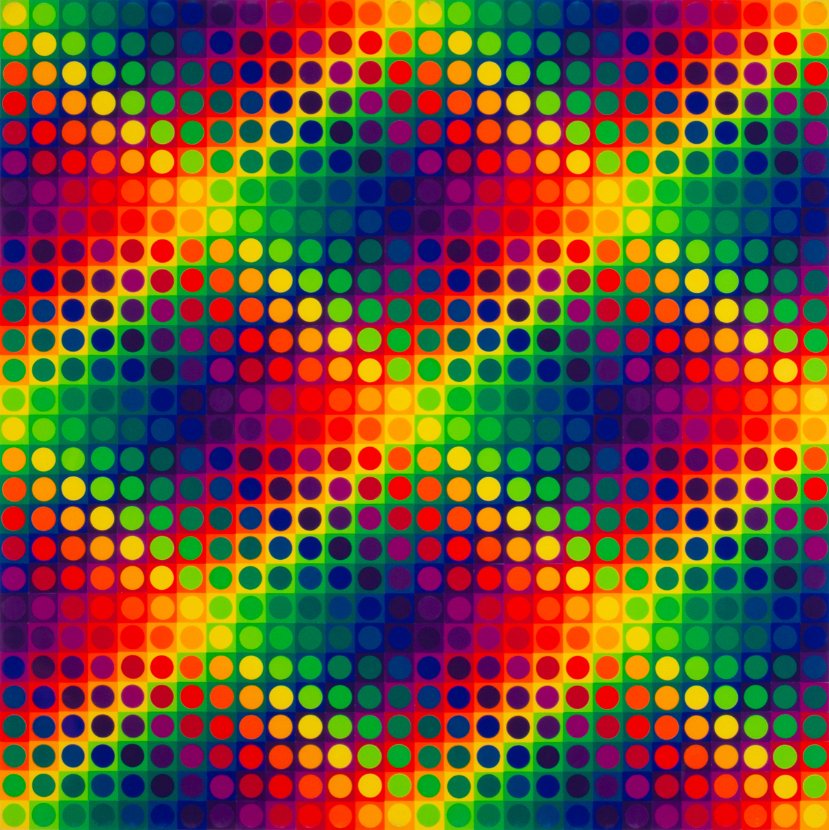

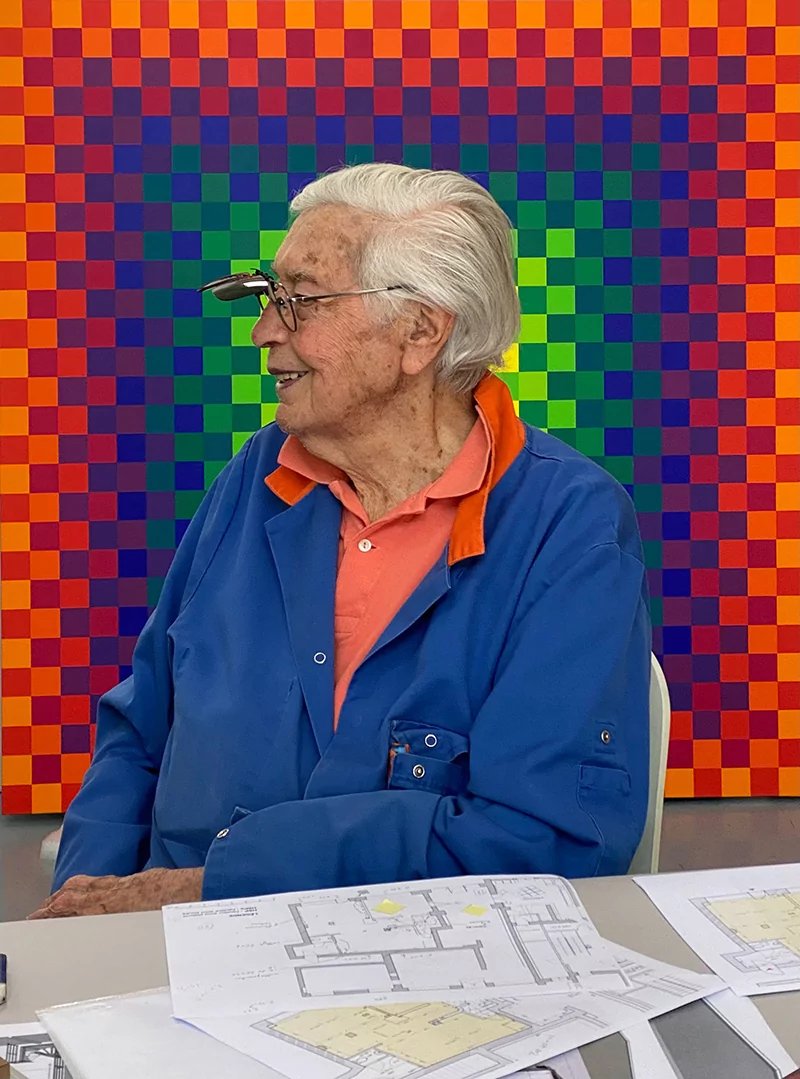

Addressed to her artistic partner and second husband who died two years prior, Niki de Saint Phalle’s Letter to Jean Tinguely was written in 1993 to accompany her new series of works, Tableaux éclatés. Thirty years later, and over sixty years since de Saint Phalle first met Tinguely, Tableaux éclatés is on display at Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois in Paris. The title can be roughly translated to “burst paintings” or “shattered paintings”—both of which embody the fragmentary heartbreak and movement of the exhibition.

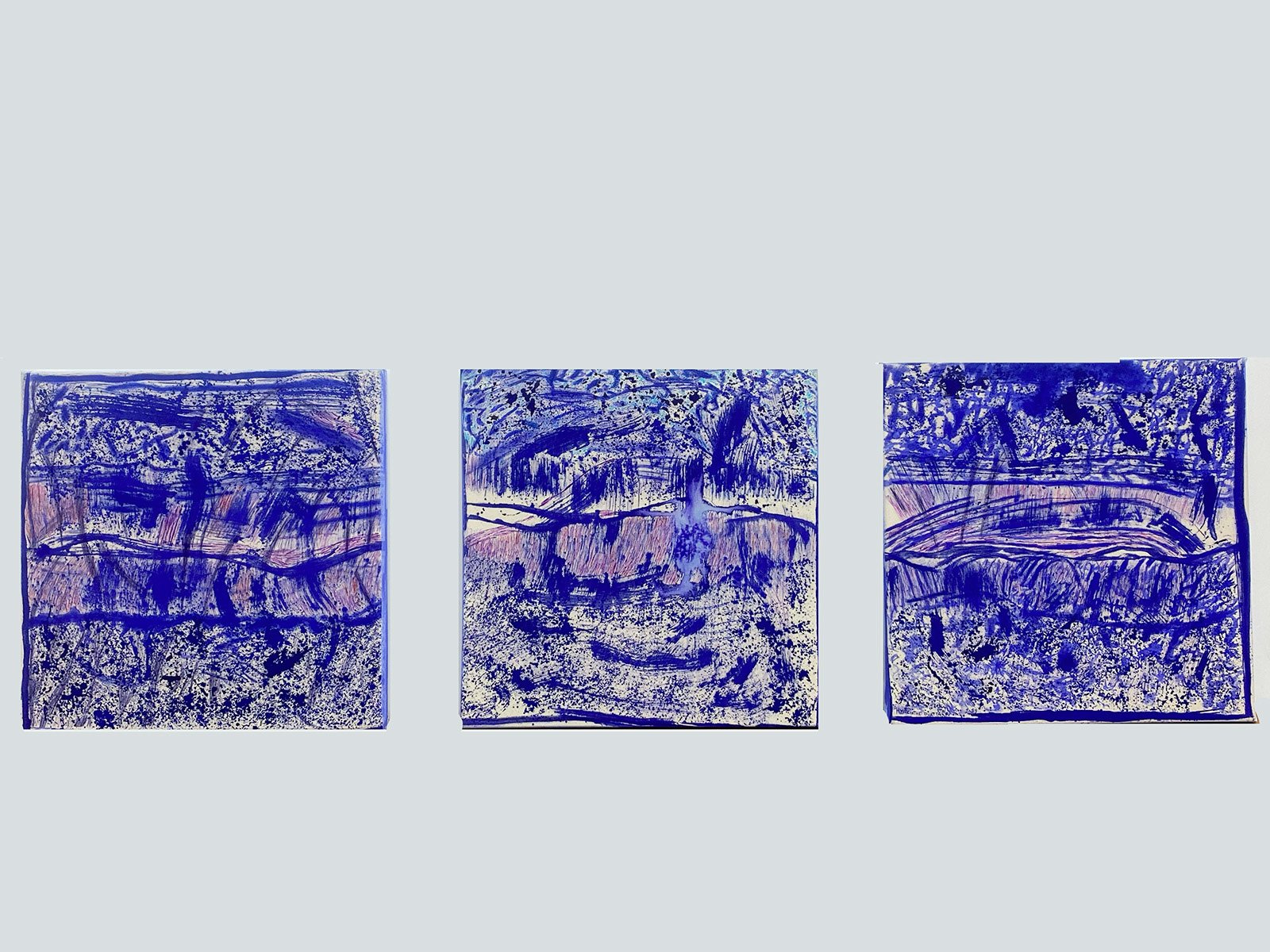

Technically, Tableaux éclatés draws on Tinguely—activated by photoelectric cells, the paintings move as the viewer approaches, similar to Tinguely’s own work. Skulls are cut open, bodies are ripped apart, and the moon rises. Then, all is put back together again. Through photoelectric sensors and hidden motors, de Saint Phalle engineers the chaos of visual death and mechanical reincarnation.

She herself says, “I am even looking forward to the breakdown (perhaps to experience the infinite joy of things working again).” Here is the crux of Tableaux éclatés: breakdown, and in its wake, strange joy. Niki de Saint Phalle’s paintings burst and shatter and then, loyally, they work again.

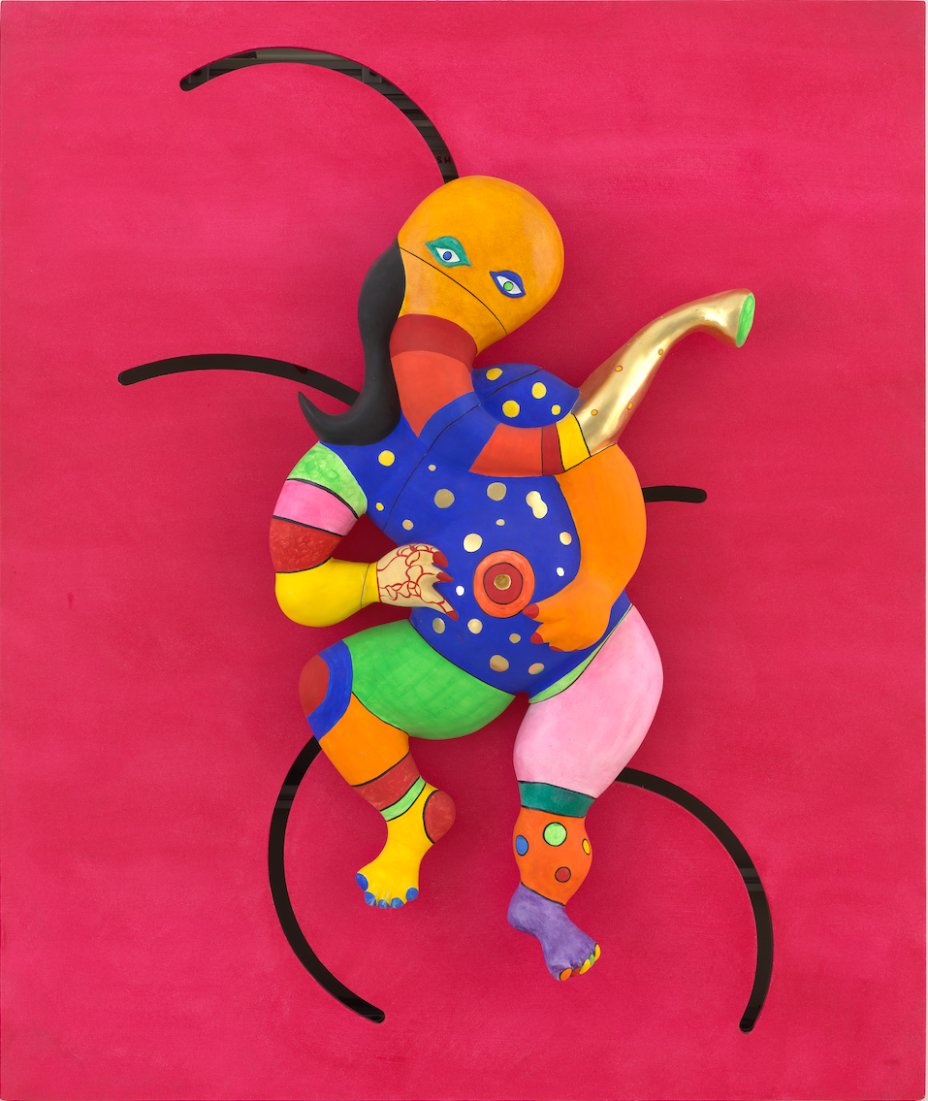

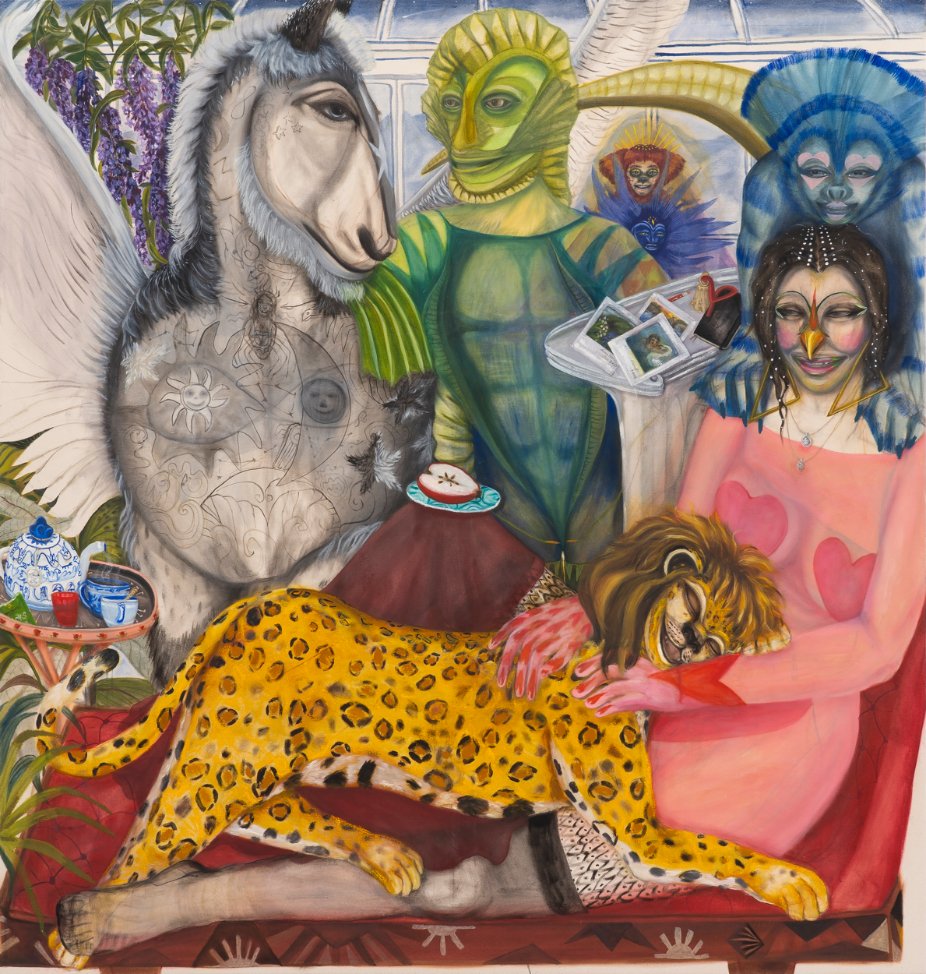

Though the form may draw heavily from Tinguely, the works themselves are unabashedly de Saint Phalle’s. Her thick, famous Nana figures sunbathe among multicolored elephants. Pink skies and pink breasts cavort while a golden-trunk Ganesh, “bearer of luck and happiness,” is flayed open, then slid back into one.

There is a jumbled chaos to Tableaux eclatés—as if Niki de Saint Phalle’s grief itself engineered the wires and motors. The image of a widowed Niki de Saint Phalle eating a banana in the dark with only the company of her gently whirring paintings is as dystopian as it is comfortingly domestic. In Niki de Saint Phalle’s own words, none of her older paintings remain. Tinguely is also gone. Now, she lives with Tableaux éclatés; inevitable, mechanical death and then a masterful putting-together—perhaps not of the one who left this world, but of the one who remains.

Tableaux éclatés is on view through October 28th at Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois in Paris, 36 rue de Seine