text by Oliver Kupper

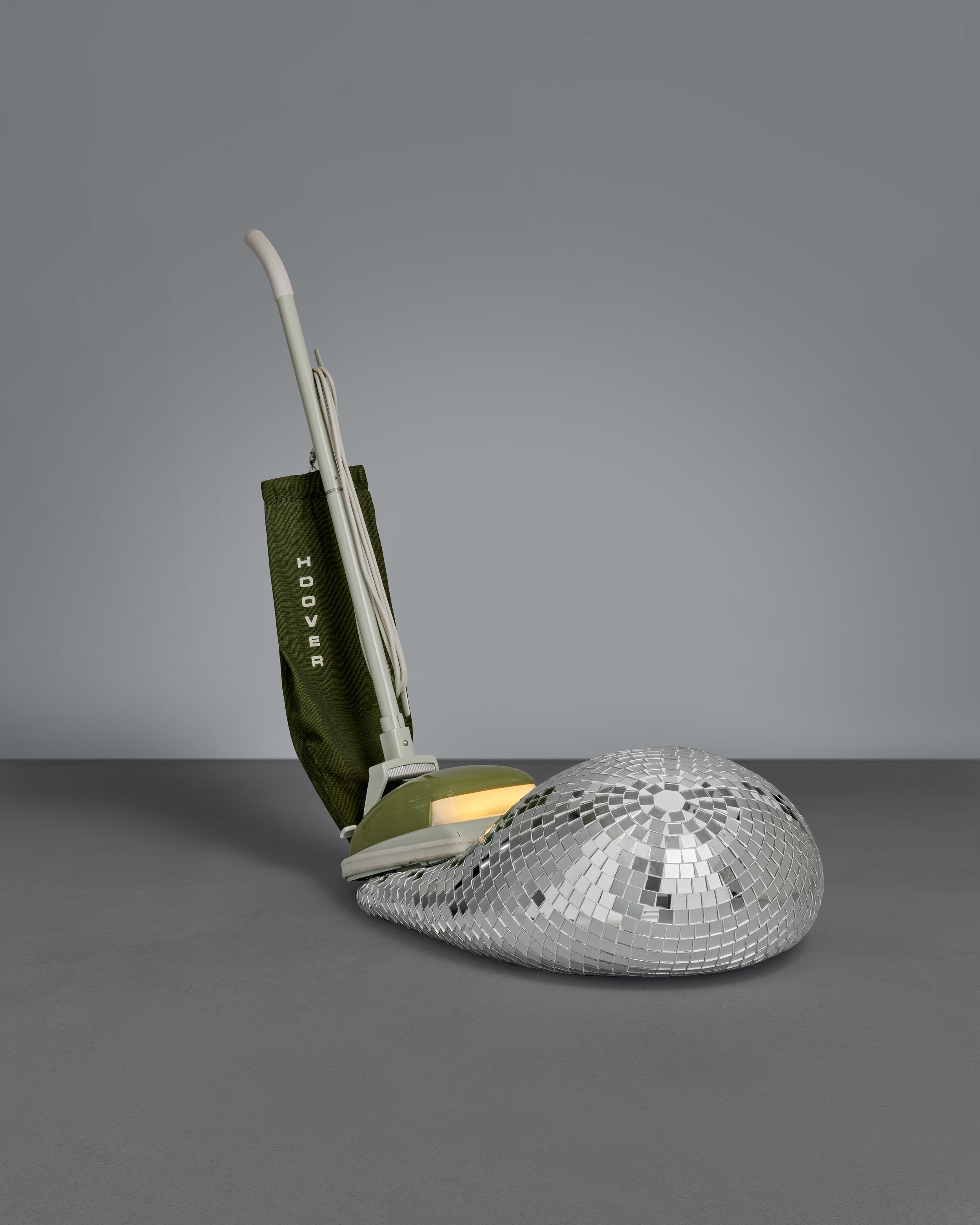

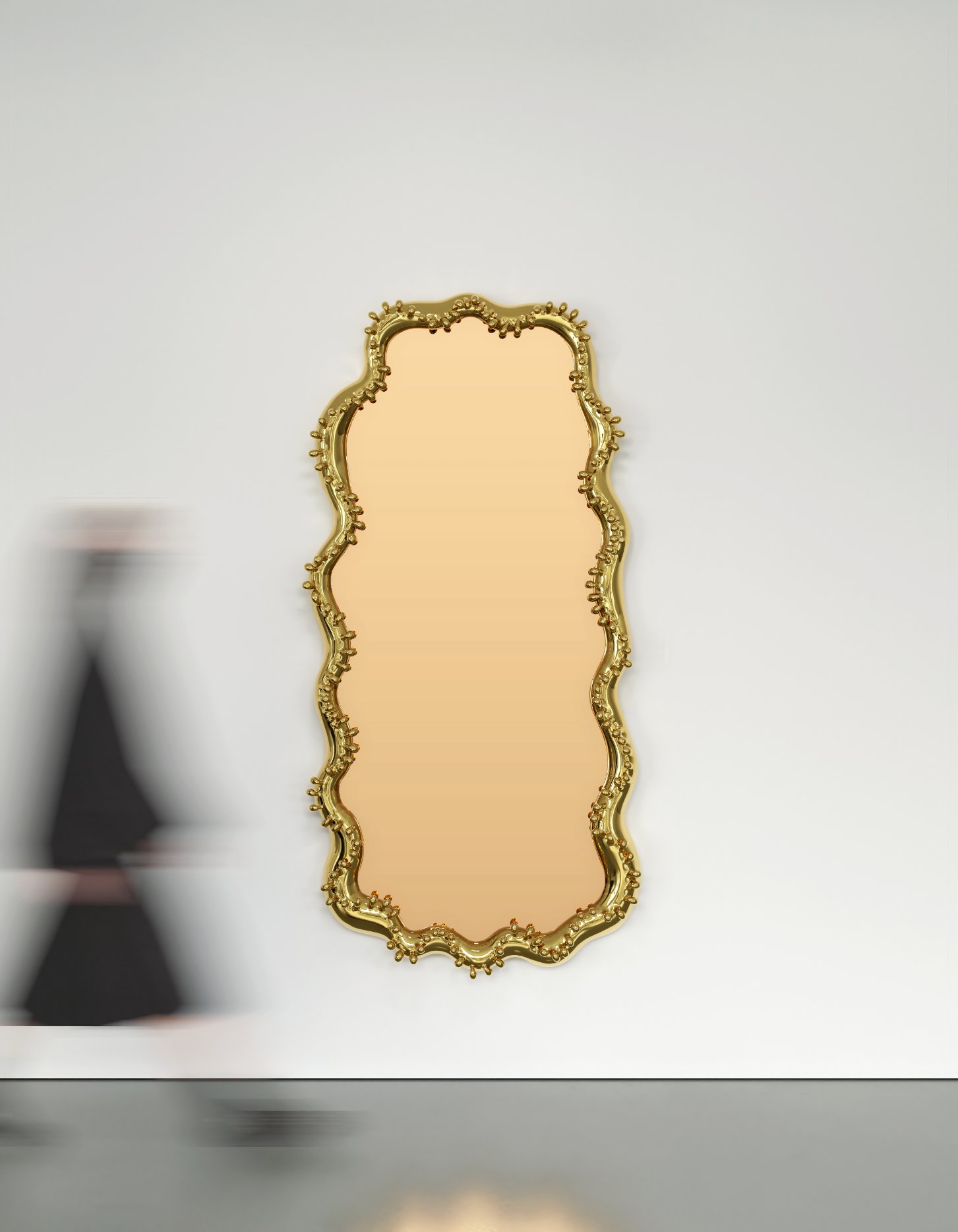

At Celine’s Women Winter 2023 collection presentation, we learned that Iggy Pop is still the second coming—even at seventy-five. And also, Hedi Slimane is one of the most important couturiers of our generation. He is fashion’s enigmatic zelig, always in the right place and always at the right time. Last night it was the Wiltern Theater in Los Angeles, an Art Deco landmark cladded in blue-green glazed architectural terra-cotta tiles on the corner of Wilshire and Western that was built in 1931 for vaudeville. The most Instagrammable moment in this shangri-la’s recent memory was an ode to a pre-Instagram era—the “Age of Indieness.” Celine’s runway show at the iconic theater, which was advertised with a blitzkrieg media buy across the city, on billboards and bus stops, opened with a larger than life Celine logo, decked out in disco lights that unfolded from the rafters, and a pulsating 20-minute original recomposition of the White Stripes’ iconic 2000 track, “Hello Operator.” After the finale, and a brief intermission, there were performances by The Strokes and Interpol—with an explosive opening act from Iggy Pop and some of his most iconic songs. He spit, he touched himself, his skin golden and wrinkled from Floridian rays and a lifetime of abusing his body on stage. The collection itself hit all of Slimane's familiar notes and silhouettes with variations on a theme: slim pants, tailored blazers, military jackets, glimmering gowns and hand-embroidery—his sartorial rebellion against the status quo, a love letter to rock n’ roll and the glamor of nightlife. If these notes sound familiar it is because Slimane is a fervent believer in repetition’s power to cement a designer’s modus operandi. In a recent conversation with Lizzy Goodman (author of Meet Me in the Bathroom: Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City 2001–2011), Slimane says, “...Repetition and consistency, quoting yourself, is key to creating the condition of the crystallization of a style and the longevity of it.” He continues, “The vocabulary may change with the time, but the syntax, the style, stays unchanged.” It may mystify some why Slimane continues to romanticize and harken back to this post-911 era of war and bloodshed in the Middle East and a burgeoning fiscal collapse. But a disillusioned pining for a confused golden age is not what Slimane is after—he is constantly searching for that clarion call for belonging. Last night at the Wiltern was proof-positive that music can be that call, and that musical movements of bygone eras were a result of this desire for communion. The question shouldn’t be why look back? The question should be why not look back. Fashion is constantly referencing itself. If done right, it can be timeless and beautiful—electrical even. Slimane quotes Carl Jung and his ideas around synchronicity for his timeliness—his collaborations with David Bowie, Mick Jagger and countless young, burgeoning musicians. His stark black and white images captured their regal visages with a crisp, eternal quality. Slimane tells Goodman, “I was surfing a wave without knowing where it would take me.” The wave eventually took him to Los Angeles at the height of Southern California’s indie scene, which grew around the time of the 2008 financial crisis. In 2016, a debilitating case of tinnitus forced him out of Los Angeles and to the more peaceful climes of Southern France. But with his most recent collection for Celine, Slimane is still blurring the line between the stage and real life, and he is still looking back, but never in anger. On the attitudes that defined the turn of the 21st century, Slimane says, “...Twenty years after, we can see it as a statement on disguise, a manifesto on the value of chaotic insouciance and stylish nonchalance.” He calls the amalgamation of fashion and live performance a “liturgical ritual.” At the Wiltern, all of this and his brilliance was on display.