Mary Weatherford and Andrea Bowers have often talked about making a show together. Bowers suggested that she would make neons while Weatherford would make paintings, a serious joke that neither would strictly hold the other to but subsequently formed the foundation for their two-person show, Drink the Wild Air, at Capitain Petzel. For Bowers, Weatherford is part of her “Beloved Community”, a quote from MLK containing two simple words that embrace the basic human necessity for democracy and love.

Mary and Andrea met in NYC around 1988 where the two were working in galleries in Soho. Mary attended the Whitney ISP in 1985 and Bowers began graduate studies at CalArts in 1990. Perhaps both young artists internalized the benefits and disfunction of the anvil of pedagogical theory dropped on them. Creativity was not a topical issue. The zeitgeist was critical analysis. Mary’s response was to move in a direction that was more personally freeing by committing to a body of work 100 percent based on her own stories. While at CalArts, Bowers was told to stop drawing and focus on content. She found her voice in the histories of community organizing and nonviolent civil disobedience and committed to using aesthetics in service of social justice.

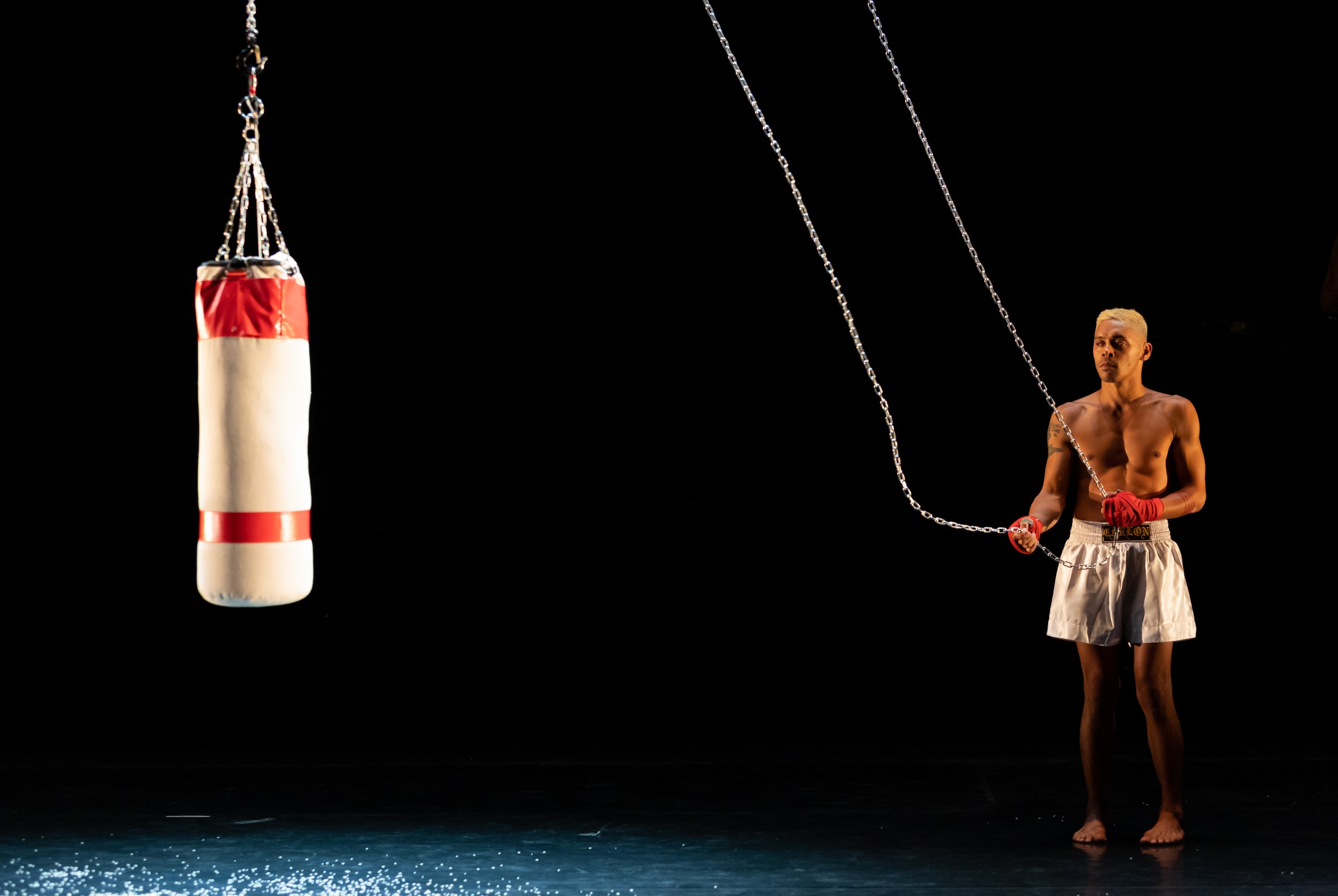

Andrea Bowers

Courtesy the artist and Capitain Petzel, Berlin

Photo by Gunter Lepkowski

Both practices are part of the tradition of women’s storytelling. While Bowers bears witness to the narratives of activists and political movements, Weatherford focuses on autobiography. In the way that women historically hid familial histories and recipes for holistic medicines in unexpected places like children’s stories and folklore, Weatherford’s stories are clandestine, hidden in liquid paint. Weatherford’s secret narratives simmer beneath the surface while Bowers insists on clarity toward action and citizenry. Both positions are viable and crucial. In a matriarchal model of community, responsibility and care, two seemingly oppositional approaches can flourish simultaneously.

Drink the Wild Air is on view through August 5th at Capitain Petzel, Karl-Marx-Allee 45, 10178 Berlin