interview by Lara Schoorl

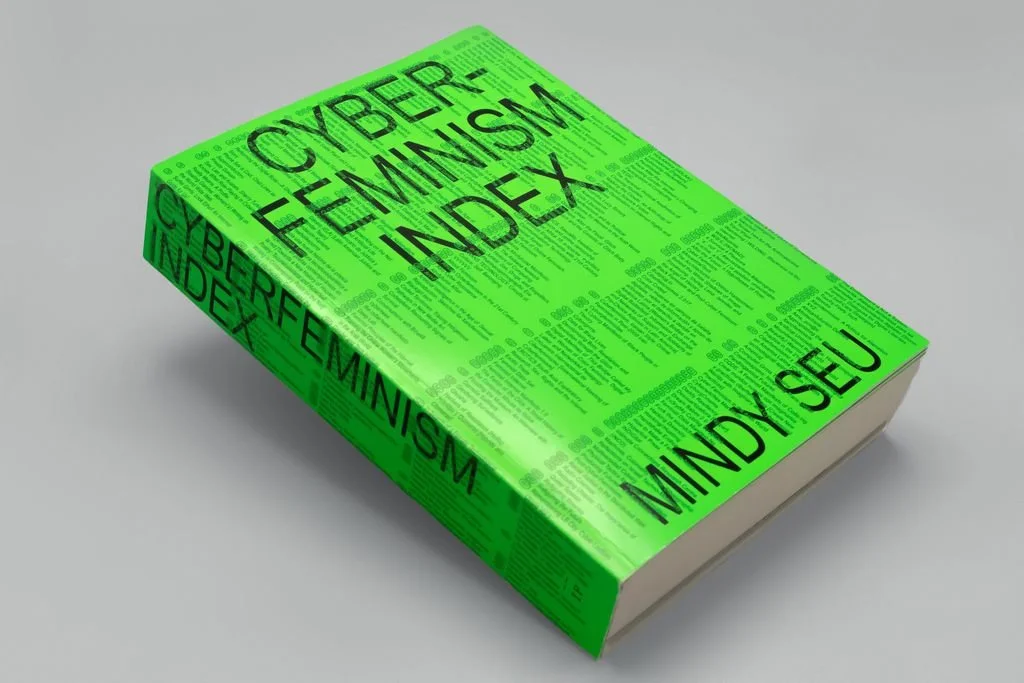

For over three years. designer and technologist Mindy Seu has been gathering online activism and net art from the 1990s onwards. Commissioned by Rhizome in 2020, the growing collection of text and imagery forms the always-in-progress web database Cyberfeminism Index. By way of a “submit” button, anyone can contribute to the project making both the creation and outcome accessible to everyone. In 2023, the Index was translated to print by Inventory Press and includes over 700 short entries with scholarly texts on the hacktivist utopias of the internet’s nascent years.

LARA SCHOORL: Do you think it is possible to invent a new type of cyber-utopia outside of the surveillant, capitalist, algorithmic framework?

MINDY SEU: During the Cyberfeminism Index panel at the New Museum with E. Jane, Tega Brain, Prema Murthy, and McKenzie Wark, we tried to trace the evolution of what's happened from the early ‘90s until now. This idea of the utopic internet was very palpable in the ‘90s because it was the first introduction to this new technology that promised global connectivity, the ability to be everywhere all the time with those that were not in close physical proximity. However, people quickly began to realize that, while the internet did afford these new potentials, it was also very much guided by the infrastructure that the internet was created on, which was born from the military industrial complex. This ultimately shapes the platforms we use now and the behaviors that these platforms perpetuate: things like surveillance, censorship, and data extraction. In my essay, The Metaverse is a Contested Territory for Pioneer Works, my good friend and Cyberfeminism Index collaborator Melanie Hoff describes what pushes people to imagine is the need to imagine: a survival mechanism to find release from the the pressures of your current reality. Some examples of this were given throughout the panel. E. Jane talked about the liberatory potentials of bespoke and local experimental music communities. Tega Brain talked about projects that consider the materiality of the internet and the physical implications of these seemingly ephemeral networks that we use. There are definitely potentials for how we can begin to think of not necessarily a utopia, but broader views of how the internet might be able to serve more people rather than the smaller minority.

SCHOORL: It seems as though the internet is almost showing us that this need to imagine is universal. Even if the status quo might work for some-arguably it does not work perfectly for any person— the internet has made visible the failures, corruptions, shortcomings, and discriminations of and within all kinds of systems. Perhaps free imagination is not fully possible on the internet itself now, or not as was anticipated, but it has made visible the need for imagination and change across the globe and all demographic groups.

SEU: Absolutely. And as you are saying, in some ways the internet did al low more people to publish these kinds of narratives online without the gatekeeping of more “legitimate” institutions.

SCHOORL: Typically, things are now translated from print to on-line, but you did the inverse. What are your thoughts behind turning the online archive into a book? Something that continues to morph organically through submissions into a more or less fixed, prescribed format?

SEU: Because my background is in graphic design, I have always believed that print and web are very complementary. In Richard Bolt, Muriel Cooper, and Nicholas Negroponte's Books with Pages 1978 proposal to the National Science Foundation, they describe how soft copies are seen as ephemeral and dynamic whereas hard copies are seen as immutable, permanent, or more reputable because of how academia valorizes printed volumes. But, with my website collaborator Angeline Meitzler, we tried to flip this hierarchy. The book, while it did come after the website, acts like a snapshot or a document of the website's mutation, whereas the website acts an ever-growing, collective, living index, to grow in perpetuity. Even since we (my book collaborators Laura Coombs and Lily Healey) froze the website's contents to create the manuscript for the book, the online database has already received 300 more submissions. The book functions as a call to action for the website to continue gathering ideas of cyberfeminism’s mutation moving forward. That said, with my publisher Inventory Press, we made sure the book was included in the Library of Congress. When creating these revisionist histories, grassroots information activism must contend with the perceived legitimacy of forever institutions by penetrating it, hacking it.

SCHOORL: Thinking about physical versus online spaces, where do you think safety and accessibility of both people, information and/ or archives, like the Cyberfeminism Index, are better achieved, online or in print? Or does a hybrid environment foster these more widely?

SEU: Generally, especially with people who resonate with cyberfeminism, there is an appreciation for complexity. It is never the binary of this is better than that, but rather seeing the pros and cons of both media and how elements of both can be used to achieve the community’s goals. For example, with print, you do have these connotations of legitimacy, but we also see the rise of sneakernets, which are physical transfers of digital media rather than using online networks as a way to avoid different methods of surveillance. With the web, there is the ability to have a dynamically changing environment that updates over time. The co-existence of print and web allows both to grow.

SCHOORL: I keep returning to the word “hybrid” when thinking about the future. I recognize it in so many of the entries in the Index: William Gibson’s cyber-space, Donna Haraway’s cyborg, E. Jane’s anecdote about us needing air to breathe, Ada Lovelace and Jacquard’s loom, and more. How do you consider a hybrid on-line-physical point of view?

SEU: It makes sense why people think the internet is ephemeral and acces-sible; we have these computers in our pockets that have become extensions of our bodies. It is harder to see the physical infrastructures that make this thing possible: fiber optic cables running along the ocean floor, or the rare earth minerals that make up our phones, typically mined in Latin America in places that have very few or non-existent labor laws. Even after our devices die, they are very hard to recycle so they end up in e-waste graveyards in Guiyu, China where people break apart the phones to sell different parts, and the remainder is burned, leading to a very cancerous environment for those who live there. expand on these ideas in a forthcoming essay called “The Internet Exists on Planet Earth,” commissioned by Geoff Han for Source Type and Tai Kwun Contemporary that attempts to unpack the materialism of the internet. For one of the people who coined cyberfeminism, Sadie Plant, materialism is a huge component of her seminal book Zeroes and Ones (1997). In it, she gives a retelling of techno-history, redefines what technology actually includes, and details the ecosystem in which technology lives.

SCHOORL: Do you think it is possible to be completely inclusive, even if attempted? Is it more conceivable for utopia to be actually plural: utopias? Or, are they indeed meant to literally exist nowhere?

SEU: Generally, universalisms cannot exist. The utopias that are evangelized do not account for the many different perspectives and demographics that true equity requires. Rather than thinking of utopia as a space, we can think of utopia as principles. There are principles that could be embedded in our current landscape to benefit the masses, such as file sharing, basic income, open borders. Lately, I have been thinking about scalability. A couple of years ago, I co-organized an exhibition at A.I.R. Gallery with Roxana Fabius and Patricia Hernandez called the Scalability Project, whose title was borrowed from Anna L. Tsing’s Mushroom at the End of the World [2015]. Scalability was also a tenant of this year's Transmediale in Germany. Scalability implies a smooth, seamless, hyper-efficient growth pattern, but the breaking points it reveals inevitably create conditions for change. Legacy Russell writes that the glitch is the correction to the machine. Instead of the glitch as an error, it is an amend-ment, a reexamination of the problem. Another activist and scholar, adrienne maree brown, and her collaborator Walidah Imarisha, introduce the concept of fractalism, the creation of principles for a small local community that can grow as a spiral, with clear mutations at different levels in order to bring in more and more people. It is this idea of constant evolution rather than seamless scalability. We’re embracing glitchiness, bumpiness, and the errant.

SCHOORL: I know the project does not aim to define cyberfeminism, but do you have a particular understanding of the word “cyber”?

SEU: I think about “cyber” in the context of how it has been used in history and through its etymology. The prefix “cyber” first emerged in Norbert Weiner’s cybernetics in the ‘40s. In simplistic terms, it proposed the idea that you are impacting the system just as it is impacting you. It’s all about feedback. Then, cyber appeared in cyberspace in William Gibson’s Neuromancer [1984]. This sci-fi novel was important because it predicted the sensory networked online landscapes that we are very much talking about today. But Gibson's Neuromancer was also shaped by the white male gaze, with fembots and cyberbabes and depictions of women with assistant or robotic-like roles. He also created a very oriental landscape that is devoid of actual Asian figures. When cyber was then fixed to “feminism” to create “cyberfeminism” by VNS Matrix and Sadie Plant in the 1990s, it felt like a provocation for feminists, marginalized communities, or women to reshape what cyberspace could be.