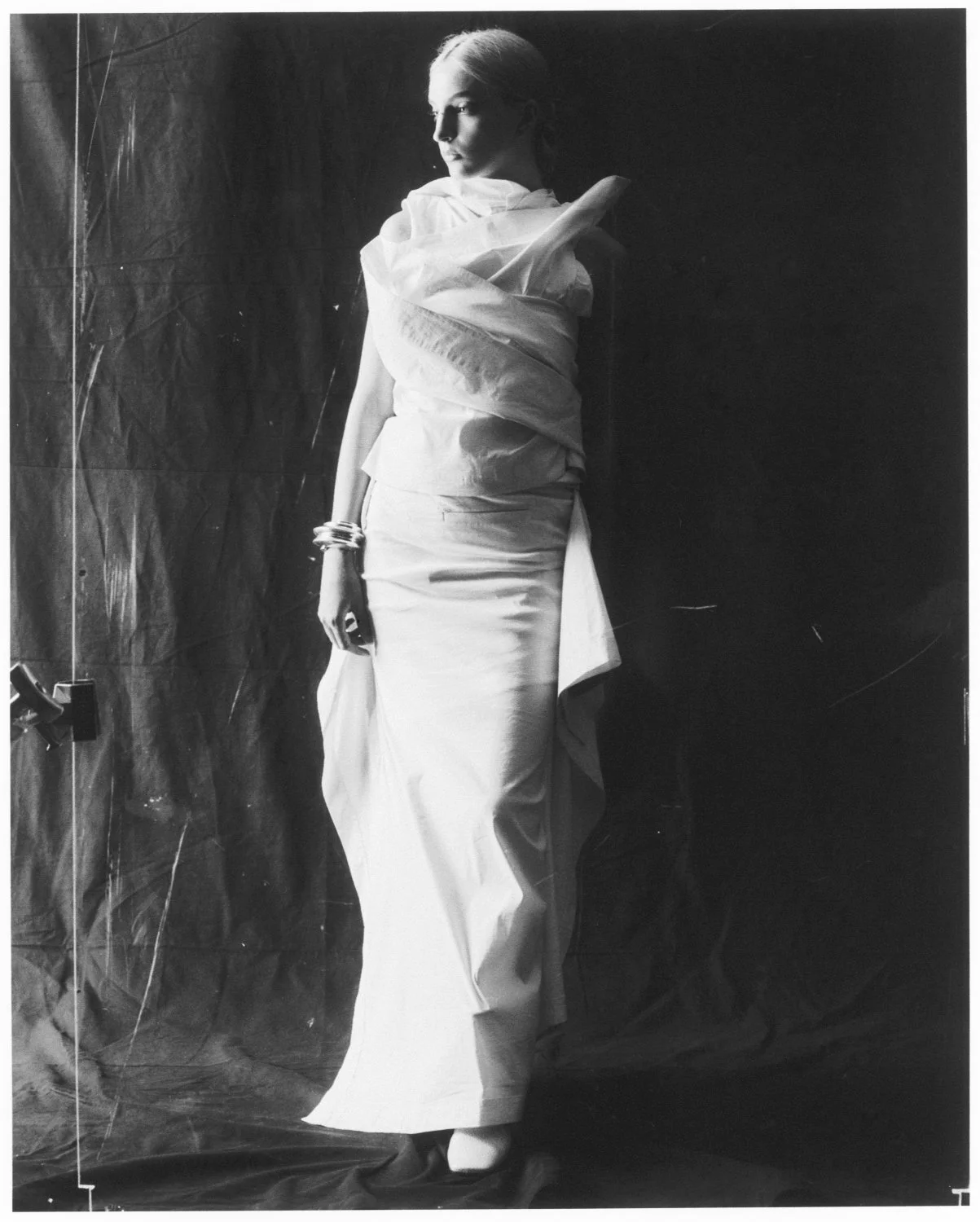

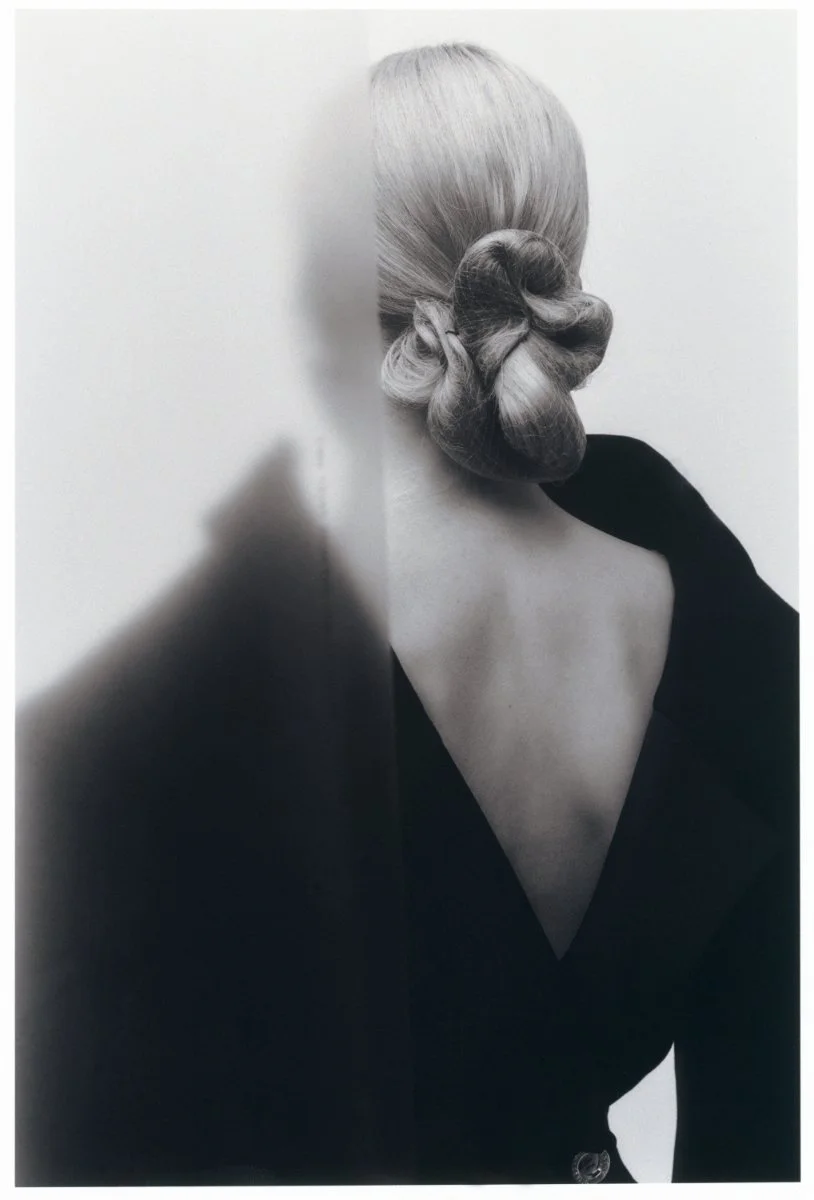

Hailing from the working-class fishing port of Grimsby, England, Betsy Johnson is one of those rare cultural multihyphenates—stylist, creative director, artist, designer, photographer, storyteller—who quietly transforms the visual language of fashion. Her influence unfolds subtly; you don’t always notice it until you can trace it back to one of her references. Her British roots inform a hard-edged style that shifts between minimalism and maximalism, punk and glamorous, dark and light. It is precisely these contradictions that have made her so successful in inventing a unique sartorial lexicon. For Betsy Johnson, work is the process, and the process is inseparable from the work itself. In response to the Work In Progress theme, objects found in Betsy’s home and studio were categorized—collateral of the creative process.

Austrian-born Martina Tiefenthaler, who served as Chief Creative Officer at Balenciaga during Demna’s highly successful ten-year tenure, approaches fashion with equal singularity. With a background in architecture, she provided a rigorously engineered foundation for the house’s reinvention of the modern silhouette. Tiefenthaler continues to reinvent herself and her practice through her recent ventures in coaching and image making. In the following conversation, Johnson and Tiefenthaler discuss the power of objects to hold memory, the role of emotional intuition amid commercial pressures, and the importance of holistic, human-centered leadership in creative industries. The pair posed themselves both the question: are you materialistic and do you hold on to things?

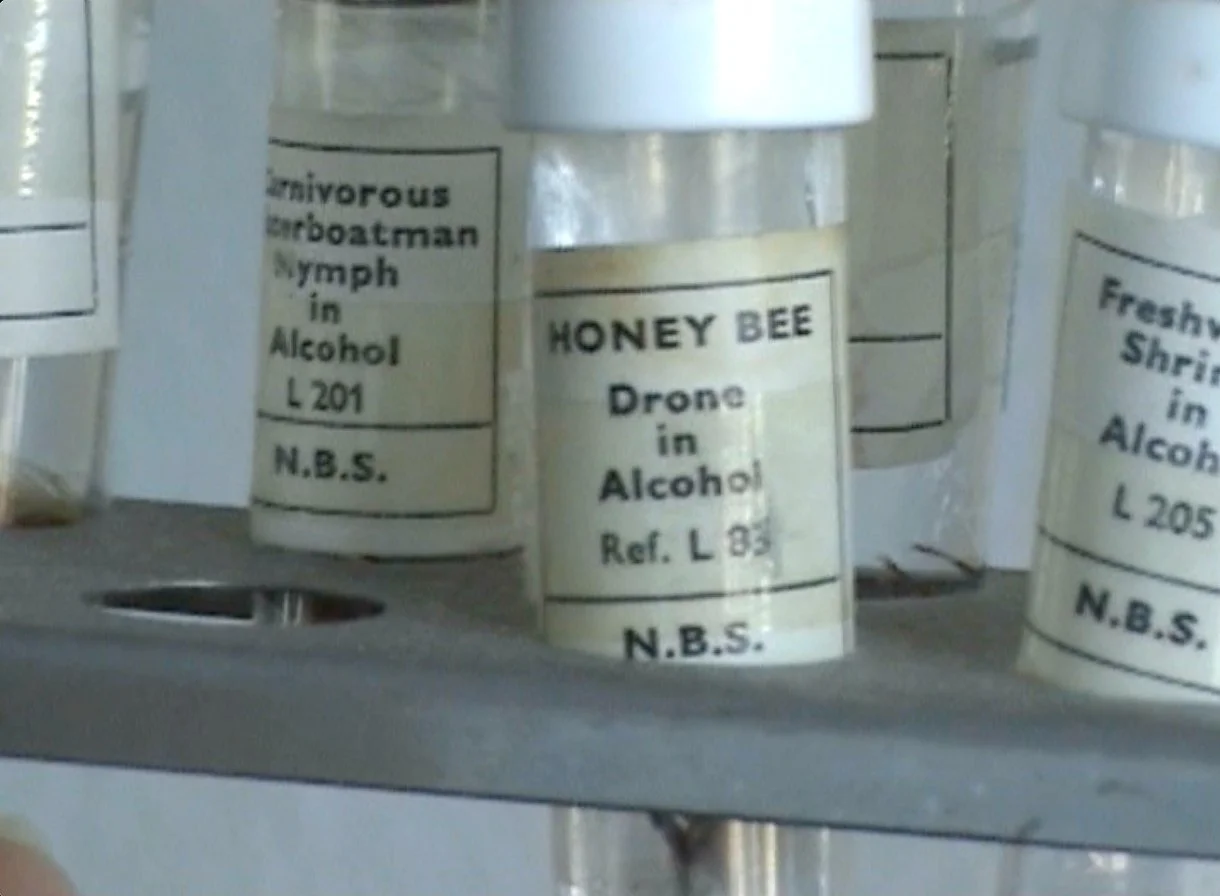

BETSY JOHNSON I didn’t think I held onto things, but I’ve been told that I’m a hoarder. (laughs) I hold onto everything from shoots: plane tickets, handwritten notes, props, labels, and a lot of printed materials. So, I’m materialistic in that way, but I don’t buy things. What about you?

MARTINA TIEFENTHALER: I do know I’m a hoarder. People don’t have to tell me. (laughs) I’m a trained designer, so the way that I look at things is really like, What’s the color, the touch of the material, the functionality, the context, who made it? How old is it? When I look at an item, it gives me information, which relates to a feeling—it makes me laugh or remember something that I had as a child, or the color makes me remember something. So, with the amount of things I own I probably look materialistic to other people, but I don’t think I am.

JOHNSON: That makes perfect sense. Most of the clothes I keep are like a pair of football shorts from when I was five years old. I keep them somewhere thrown in the corner of my closet, and somehow having these personal effects helps steer the work. Or if I feel like I’m losing touch with my creative path, I always go back to these notes and objects. They help re-center me.

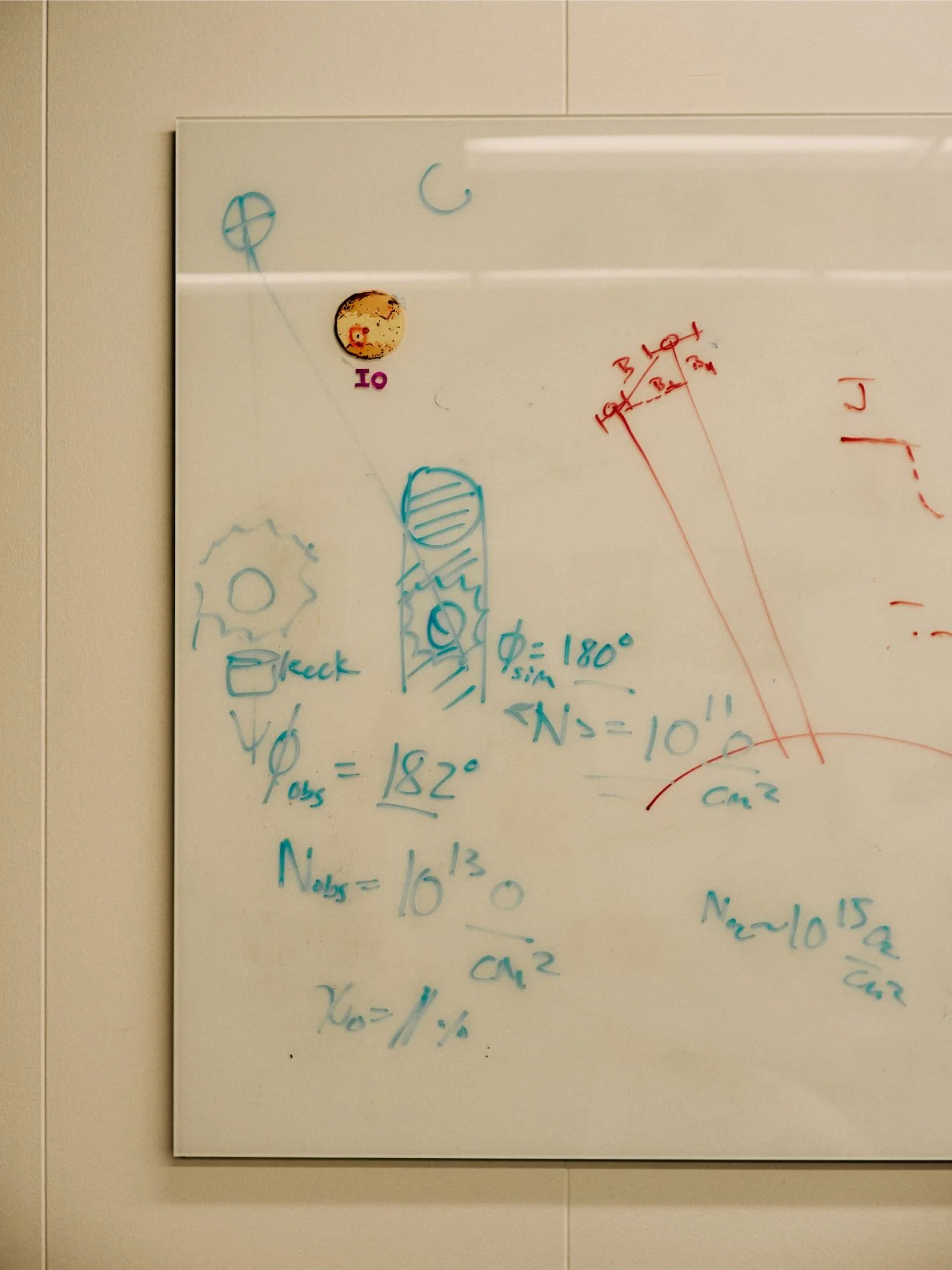

TIEFENTHALER: As creatives, we need informative material. That can either be physical: objects, products, material, or it can be digital, like imagery. And then, the third category is everything that you have saved in your mind: memories, conversations, ideas. We need all this informative material to feed the process and to continue doing the job. The part that I’ve always liked about my job is that I’m able to go into moments of research, collect things, make edits, and then decide what is relevant right now to kick off the creation process. As a designer, being a hoarder comes in handy.

JOHNSON: There’s something you just said about feeling, which relates to something I was telling my mom recently. I told her, “I’m experiencing multiple layers of reality because when you have something physical or visual that you’re dealing with, it takes you back to a feeling or an opinion you have on something. That opinion then becomes contextualized by the image or the object. All of it gets layered together, and boom, there’s the idea. A lot of people now have a concept and a reference, but they’re missing the emotional aspect that ties the whole thing together.

TIEFENTHALER: I totally agree. So much of my career has been very commercial, with the primary target of generating revenue through sales. No matter how much I was telling myself that I was working for companies that were more on the conceptual side, the truth is, they had a commercial purpose. And as a professional creative, you have to fit into frames, whether it’s timing or other constraints, but you have to shoot ideas all the time, which can be tough. So, you learn how to work ignoring your feelings, coming up with more ideas, whether they’re good or not. Sometimes you have to go with an idea because the deadline is there and the timeline doesn’t allow the process to continue. That’s why I like to talk about feelings. It’s ironic that you want to create something that makes you feel good when you wear it, but the structures in which we work make it difficult to feel good.

JOHNSON: That’s interesting because my career is freelance. So, the balance between the commercial work and my personal practice sometimes gives me whiplash. You do have to shut down your emotions. Sometimes I went wrong in my formative years by approaching commercial work as if it were my personal practice. I would treat a commercial project as if it were my child. It was a process for me to find the balance between doing the job well and separating myself. Sometimes I take on back-to-back commercials, where there are tons of people and so many different expectations. Then, I need to find respite in the personal.

TIEFENTHALER: Yeah, that’s something I’m doing, working on non-commercial, artistic projects. Doing that has always been a tool for me to take a breath and do things at my own pace. If you don’t have to sell and you don’t have anyone telling you when something has to be ready, you actually experience ultimate freedom. The process is my goal, rather than the outcome itself.

JOHNSON: Do you ever sit on projects for ages? Sometimes I work on something personal, and I sit on it for two or three years. I either forget I’ve done it, or I’m too much of a perfectionist and never feel it's ready to put it out.

TIEFENTHALER: Having worked in given structures, I always thought that a project is something that has a starting point, the process, and the result. Therefore doing things that may never come out or don’t have an ending cannot be defined as projects. But with the new freedom I have, I’m trying to question how I was trained to label the way I work, and I want to get rid of labels. So, I would say I’m currently busy with a hundred projects, some of them are running for ages. They’re like different channels, some exist only in my mind.

JOHNSON: It’s refreshing to hear this. I had a long-term retainer project and after that I’ve been more into personal creative research and development. But it’s been interesting to explain to my accountant where all the money went. I was like, “I’ve been in research and development.” And they’re like, “But you’ve been trying this and you’ve been trying that.” And I’m like, “Yes.” Because when I enjoy where something is going, I have to just let it unfold, and then another path makes itself known. It’s not through anyone wanting to pay me to do something, but just because something presents itself, and that leads to another thing. So, on paper, I might be working on somewhere between sixteen to twenty projects, but it’s probably only three with some sort of timeline. What you’re saying is reassuring to me, because I can really start to wonder what I’m doing. It can feel like everyone’s focusing on their one thing and doing it well, and maybe I just have ADHD. But actually, it’s just the process of doing.

TIEFENTHALER: We have to get to know ourselves as individuals and figure out how we like to operate. At the beginning of our careers, when we learn, we need other people to show us how things are being done. Then it takes time and experience to find our own ways, and it would be easier to establish these if we were all to stop trying to put people into drawers, saying, “Okay, this is what they do, and that’s the number of projects that they do, so that’s how successful they are.” It’s complete nonsense. I’m astonished by how we hold onto this way of thinking as a community and as an industry. It’s all about who’s hot, who’s not, who’s busy, who’s successful. It’s very degrading, and it doesn’t make the community any richer, it’s really destructive.

JOHNSON: It makes a lot of people lie, also. They like to inflate what they’re doing, and then it becomes this pissing contest of who’s doing what. To me, the goal is to be less busy, so you can then figure shit out. What’s ironic is, all of the least successful projects that I’ve had on paper—whether it be financially or social media engagement—are my favorite things I’ve done so far. And all the things where everyone’s like, “Wow, that thing was so cool,” I’m like cringing inside.

TIEFENTHALER: I understand. Often the more liked projects by the audience are the less liked projects by the creator. The challenge is: what do we do with the audience? How much do we need it? Do we really care about it? In an industry that is so much about looks, I’m still struggling to find my way of dealing with it. You don’t need the audience in order to be creative, and that’s very liberating. Nobody can hold you back other than yourself. You will always have people who like what you do and people who don’t.

JOHNSON: Do you believe in networking? It’s something I’m terrible at. Sometimes I think I need to go out and see things, and then I don’t because I have anxiety and am a bit of a hermit. I’m curious about your take on this.

TIEFENTHALER: I’m not very good at it because I’d rather cook dinner at home and go to bed early than spend a night with people who make me feel weird being around them. But the work we do relies on teamwork, and having clients, and that only works if you are in touch with people. It’s wise to create your own community. I don’t think you have to attend all the events. But maybe calling someone and say: let’s meet and have a coffee together, is a good way of connecting. To me this is completely new (laughs), I was always hiding in the office, I like it.

JOHNSON: I don’t know about you, but when I was at school, I wasn’t really popular. Then, I left my hometown, did all these things, and out of nowhere some people thought I was cool. It was a strange phenomenon when I was about twenty-three to come into this industry that’s so based on being cool, and then you have people thinking you’re cool. But not everyone has the best intentions when they want to be your friend, especially in those spaces, so going through that and coming out the other side has been a strange but nice journey. How was your transition into this weird space?

TIEFENTHALER: I don’t walk around thinking that people find me cool. This is something I’d rather question. If someone tells me that they find me cool, I feel flattered, and I’m happy to hear it. But if you don’t think you’re cool, you don’t have to maintain it. And instead of aspiring to be cool, you can aspire to be content.

JOHNSON: I agree. Your life is just what you are doing minute to minute, so you have to enjoy what you’re doing. My team is crucial to my livelihood and even my mental well-being. They are the people I talk to every day. It truly is a collaborative effort, and this is what makes me really happy.

When you have an “online image,” you do one post and people form opinions, and that’s how they perceive you.

TIEFENTHALER: People read code unconsciously. You see something, and then it reminds you of something else. So you code what you see. For many years, I’ve been dressed only in black, and nobody ever asked me why. Everyone just thought, she’s goth, and I’m totally not goth. I don’t like the music, and I don’t know much about the culture. I started dressing in black because I had an intense job creating thousands of products per season. Working on colors, materials, shapes, forms, silhouettes—the whole day. I simply didn’t have the inspiration in the morning to style my looks. It was easier for me in the morning to choose an outfit based on my feeling: choosing only the fit and the fabric that I wanted to feel on my skin that day, not also the color. It was a very pragmatic decision. But people reading codes thought, she’s a dark, tough bitch. (laughs) But I don’t think I am. I always thought fashion people should know better, but maybe they don’t want to know better.

JOHNSON: For sure. It’s funny, though, no one thought I was goth; they just thought I was a bitch. (laughs) There’s this thing about automating as many aspects of your life as possible, so you can do what you want to do with your mind. I’ve been wearing the same cargo pants for maybe five years. I have three pairs because I wear them every single day when I’m working. It allows me to get on with my shit, and it’s the same for my team. When I’m looking at all these pieces, I don’t want my team to be in anything but black. I can’t be distracted. I just need to lock in. But yeah, someone saying, “I thought you were a total bitch before I met you,”—that sentence in itself is wild.

TIEFENTHALER: Ultimately, you gotta be quite fierce in order to make it, because there are quite a lot of people, often men, standing in your way. So, how do you get through this barrier? You have to have thick skin. It’s easy for other people to say, “Look at her. She’s doing well. She must be a bitch.” But it’s so destructive. Why not say, “Oh, she’s successful. She must be really good at what she does.”

JOHNSON: It’s very counterproductive to getting more women in spaces. I want to ask about your coaching, because it’s only been the past year, but half the time when I was going through a rough patch, my team became the reason I kept making things. I was getting more out of mentoring people on my team, and that back-and-forth mentorship became so focal to me. That’s something that I wasn’t expecting. I don’t know if this nurturing side of things has to do with being a woman.

TIEFENTHALER: I enjoy the coaching, as it’s about the human. A lot of people in the business don’t dare to let out their human side, men or women. Though in our industry, it’s all about team work, it’s rarely something you can do completely on your own. The one thing we do the whole day is communicate with other humans. Secondary to that, we create, we design, we direct, we style. It’s helpful to be human and prioritize the way we work together.

JOHNSON: When we’re in fitting, we’ll always joke and I’ll say, “It’s a safe space.” Our job is to try rubbish and most of it won’t look great, but it’s that one thing we find in the fifty things that’s good. This industry can be so narcissistic, and it has this social side that can be not just mentally, but also physically unhealthy. You don’t get the best out of people in these toxic environments.

TIEFENTHALER: Yes. I think this is because it’s a race for very few seats. If we gave the same attention and value to all the different roles, the whole atmosphere would relax. Likewise, if we focus all our attention as a company on two or three people, then the tension begins because it feels like there’s not enough space for everyone. These environments become very toxic because everyone’s worried they could be kicked out at any minute. I do not believe the artist has to suffer in order to create. It’s a myth.

JOHNSON: I’ve met a few people along my journey who romanticize this, and I’ve clapped back like, “Look, I’ve been a struggling creative. It’s not a nice place to be. It’s something that you spend every day trying not to be. But it’s your mindset, or your financial position, or sociopolitical situation that you’re in. I don’t want to be suffering. I want to be doing yoga, eating good food. I want to be on a call with a team that I love. A suffering artist is the last thing I want to go back to.” I know people who have chosen that facade, and I don’t know how real it is to them or what they’re actually experiencing, but it’s absurd to me.

TIEFENTHALER: It’s usually the non-creative people who have this idea. But providing a nice environment means better business too. People quit less, they are more invested and have fun doing what they do.

JOHNSON: The premise of creativity is to play. You have to feel safe like a child and protected by your leadership, so that you can feel relaxed enough to venture into the creative process. When I’m hiring people, I’m looking for people who are just obsessed with what they do. They’re the people who really show up every day and contribute to the creative conversation that we’re having. They’re not looking side to side, and they don’t care about what anyone else is doing inside or outside our studio.

TIEFENTHALER: I have to say, (laughs) almost everyone I know isn’t able to do that. But, of course, if the target is to sell and the industry is competitive, the orientation doesn’t go straightforward; it goes left and right and backwards. It’s also called merchandising. A threat to creativity. I have made many mistakes in my career, and I take responsibility for those mistakes. However, when I analyze why I made poor decisions or behaved in a way that I’m not proud of, it’s mostly because I felt unsafe. I was irritated in some way, and that causes you to lose focus.

JOHNSON: The industry can really make monsters of some people, but are you optimistic?

TIEFENTHALER: Generally speaking, I’m both pessimistic and optimistic. I’m an extremely sensitive person. So when I read the news, I’m a pessimist. I do not see anyone getting it together or making change for the better. However, I love creating, and I’ve realized creating is an optimistic act. Like to cook for example, it’s a tool to survive. I want to be alive, I want to be healthy, and I want to take care of myself.

JOHNSON: When I learned you were vegan through mutual friends, I was like, Wait, what? Someone who cares about the planet, about their body and themselves, is clearly self-aware and aware of the world around them, but is also in this really high position in an industry that doesn’t care about any of those things. This person exists?

It was reassuring because I can remember my first fashion week in London. I was nineteen, from Manchester, staying on someone’s sofa, and I just called my mom and cried hysterically. I was like, “Oh, this isn’t for me.” I thought I might find a corner for myself in fashion, but it ended up feeling like it was in complete opposition to who I was fundamentally. I felt like these people don’t talk about the things I find interesting. They don’t do things I find interesting. But people think they’re important and want to take their photographs. It felt like my whole world was shattered. She really talked me off a ledge and was like, “I think that’s good. You’re not interested in those things, but you like what you do. You know what you want for yourself. Ignore all of that. They don’t have to be your people.” That helped a lot. And over the years, I’ve found people that I do resonate with.

TIEFENTHALER: I relate to that a lot. Life is a journey of figuring out where you want to be. Where is your place at a particular moment in time, and do you feel content with the place that you have chosen? It’s a process. You can also make peace with sometimes making the wrong choices. Once you realize that life is trial and error, you try things out. If they work, you stick around. If they don’t, try to get out of there. That’s good advice if you want to have a career in fashion. If you end up being with a group of people who like to talk about the same things you like to talk about, then that’s the right place to stick around. But you need a bit of time to find that environment.

JOHNSON: Yeah, that’s how I ended up feeling. This last year, I’ve been the most content. On paper, and in other people’s eyes with whatever metrics they’re using, I’ve maybe been the least successful. But I’m happier in my day-to-day routine than I’ve ever been in my life, and growing. It feels like I’m just getting started.