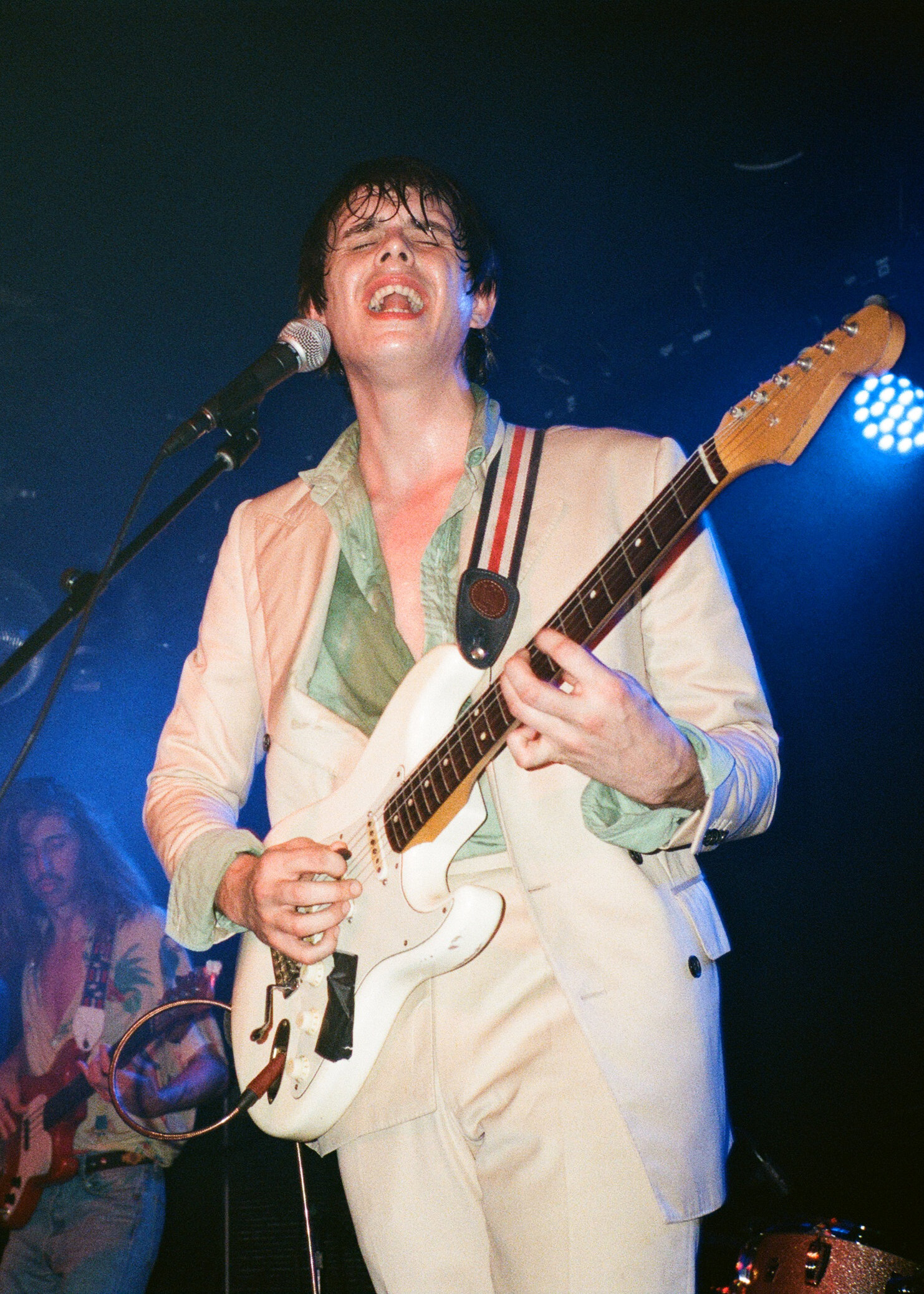

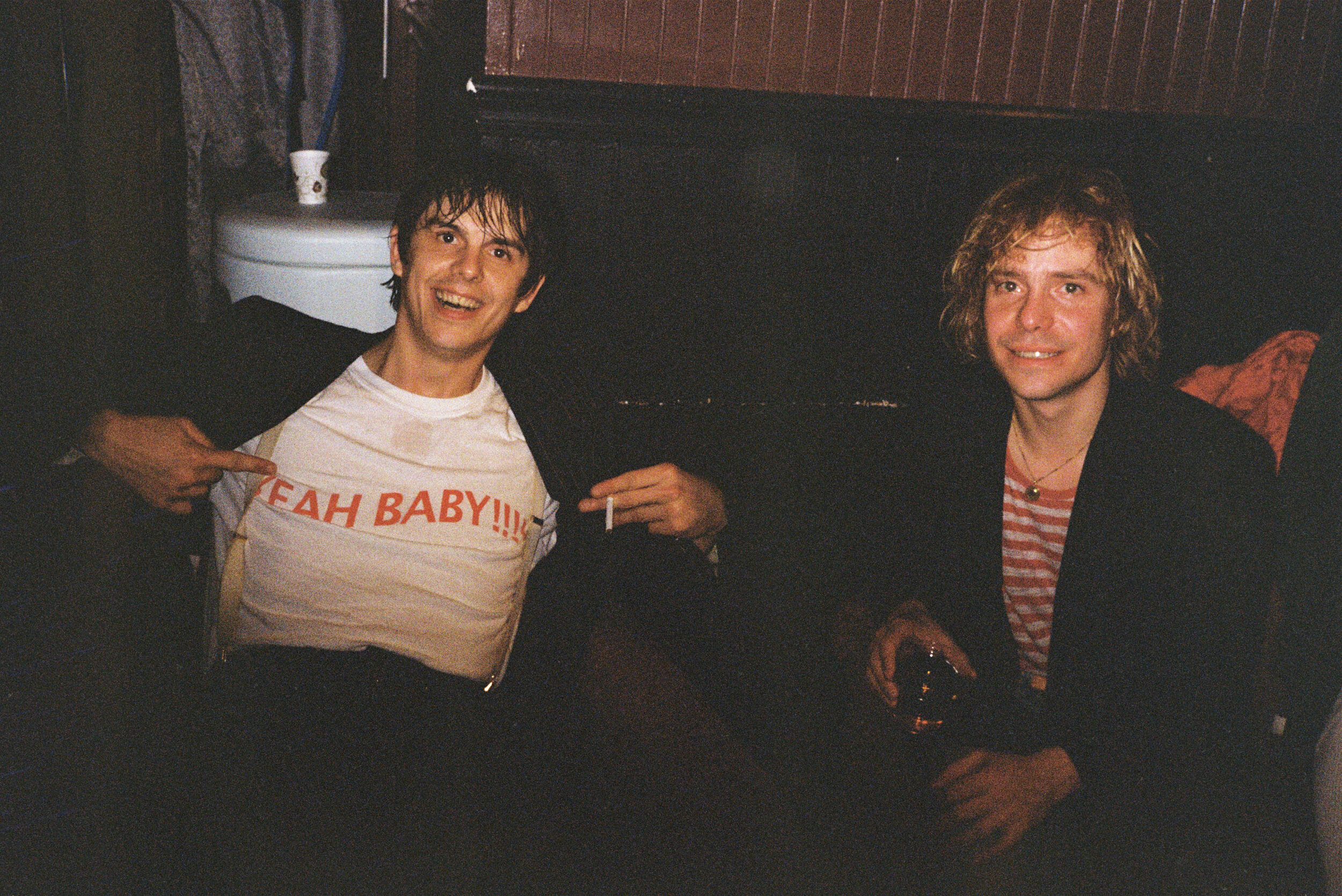

interview and photographs

by Agathe Pinard

The Parisian duo Papooz became well known in France thanks to their summer 2016 melody Ann Wants To Dance with its sensually whimsical music video directed by artist Soko. They released their second album, Night Sketches in 2019, which encapsulates the essence of France’s warm summer nights: sipping white wine after spending the whole day being sun-kissed on the beaches of Cap Ferret (where Papooz recorded their first album), or enjoying the freshness of an ice-cold drink on a terrace with friends after suffocating in the streets of Paris all day.

This year’s summer plan might not be as sandy and salty as we’d once imagined, but we can only hope for more sexy new tracks and clips like Papooz’s latest sumptuous release. Straight from the garden of Eden, this forbidden fruit was directed by Victoria Lafaurie & Hector Albouker “in the year of Covid-19” and features goddess-like Klara Kristin, who made her film debut in Gaspard Noe’s Love. Papooz’s Armand Penicaut and Ulysse Cottin quarantined with their musical crew at La Ferme Records to prepare the new album, yet to be announced. I sat down with Papooz a couple months ago, before their show at the Moroccan Lounge in Los Angeles, before the world went into quarantine.

Tell me about your upbringing, did you grow up in a musical family?

Armand: Kind of, my dad’s family is made of mostly classical musicians. They all studied classical piano and went to the Conservatoire de Paris. And my grandma, on my mom’s side is a piano player as well.

I believe you both met through mutual friends and started playing together mostly with guitar…

We had some friends in common and he’s a bit younger than me. He was seventeen, I was twenty years old. Basically we used to meet up and smoke joints at this place in Paris, called Le Jardin du Luxembourg. We just started hanging out together and it was the beginning of his musical career because he had just started to learn how to play the guitar. He really dived into it for three years and we started recording songs together at each other’s house just via Garageband, you know, the software. There was no career plan, just hanging out with your mate and then it evolved from that.

You started music as a lo-fi band and Night Sketches is therefore your first studio album. How was the transition?

It’s our second studio album in the sense that the first album we made was made in a house, Ulysse’s parents’ beach house in Cap Ferret. It’s equipped with professional studio gear so we recorded music in pretty much the same way as we would have in a “normal” studio. It’s the same process. It was a bit more lo-fi but the second one we went in a really old, amazing studio near Paris called La Frette (Marianne Faithfull, Arctic Monkeys and Nick Cave also recorded at the Manor/Studios.) The transition was kind of the same, the goal is just to have a good time playing music with your friends. You’re trying to catch a moment, like photography. It’s the same process whether you’re in a little room in front of your computer or a massive studio. It’s the same way of building music, the same layers of tracks…

I’ve read that you spent a lot of time conceptualizing your album Night Sketches. What was the idea behind it?

At the beginning, we were working at night and long sessions, just Ulysse and me. At some point, all the songs that we’d been working on sounded a bit dark, disco-ish. So, we kind of achieved something musically before adding lyrics with the same kind of vibe and ambiance about relationships and night life and appetite for destruction, that kind of stuff. It’s like a fake concept album. We didn’t sit down thinking, let’s make an album about night life. At some point we found out that was a nice direction that we could go in. It’s a fun album. I like the vibe of it.

That was going to be my next question, you said that you start with the music first, is that what your usual creative process looks like, music first then lyrics?

Kind of. We wrote only two tracks together for this album. Normally our style of songwriting is: I get up in the morning, take a guitar or a keyboard, and I try to write a song. He does the same thing and then we show the songs to each other. There has to be some lyrics for me to show him something because I really believe that songs need to have a powerful meaning. This is why people can hum to them and chant them.

So, you both work separately and then come together…

Yeah. Normally I write a song, go to his house to show him the song, and if he likes it, we work on it.

The video clip for You & I is inspired by the Ramen Western Tampopo, but also references Michelle Pfeiffer in Scarface. Can you talk about how you conceptualize this kind of video? Are you the ones behind the making of the videos?

Yes, we’re behind every video we make. I really try to write the script with whoever we’re working. We’ve been mostly working with the same person, which is my girlfriend, Victoria Lafaurie. We just have a chat while listening to the tune and sometimes we even have an idea before recording the song. She came up with this idea of duality for this video. We could each have a twin, which was easy for me because I do have a twin brother. Finding a twin for Ulysse was going to be kind of a drag so we had this idea of little demons and angels like you can see in Tex Avery or Tintin. We just fucked around with that concept and wrote it together, and then she shot it with a friend of ours, Leo Schrepel, a really great cinematographer in Paris.

Did you watch Tampopo right before?

No, but all of us are big movie geeks and everything we do is based on something that’s already been done. For Tampopo, the scene with the egg, we thought it was so romantic. There was also a scene with an oyster but it was a drag to try to do it. The lights warm up the oysters and it gets disgusting. It was more like an homage.

In how many takes did you get the egg scene?

I think only two because we shot on film. We try to do every clip now on film because it looks so much better, in my opinion, so you cannot redo anything. So everything was shot in one take or maybe two since our budget is pretty tight.

You shot with a Super 8?

No, that was a Super 16.

I know it’s your first time doing a US tour. That’s an interesting time to be touring here, right in the middle of the Democratic primaries. Do you keep up with American politics? Any thoughts on that? (The interview was conducted in March, a couple days before super Tuesday)

We don’t understand American politics. We understand what it means for the people of the world to have some kind of symbol. Obama was a better symbol than Donald Trump. It’s hard to understand how the system works here with the Electoral College. I do keep an eye on it though, it’s all over the press.

I think whoever becomes the next American President is impactful for the rest of the world in some way.

Yeah, but I haven’t seen the world change that much since Trump was elected, from Paris I mean. It’s the same.

You’ve been playing on the East Coast, Canada, then Portland and San Francisco, and you’ll be heading to Mexico next. What was your favorite city to play so far?

We did a whole buckle of the States. Every city has been fun to discover. San Francisco has this kind of vibe you know, when you’ve never been there. When you see it for the first time, it’s quite amazing. California, I have to say, after going to Canada where it’s freezing, feels great.

I know you’re big fans of jazz, have you been to any famous jazz bars yet?

We went to a blues bar in Chicago. House of Blues. The tourist thing, you know, but I enjoyed doing that. We won’t have the time in LA because we’re leaving tomorrow morning.

I was wondering if you could ever see yourselves working somewhere other than Paris, or if it holds too much of the inspiration you need in a city?

I mean, I’d love to live in LA because it’s so soothing and the lifestyle is so different than living in Paris. But you know, you live where your love is, or where your friends are. America is so expensive as well.

Are there any projects you’re going to take on once the tour ends and you go back to Paris?

Yes, we’re in the process of recording. We just released a song but we’re in the process of recording an entire new album in the spring. If everything goes well, we might be back in America before the end of the year with a new album.