Everyone in the art world knows that Los Angeles' art scene is going through a frenzied and near-maniacal renaissance. But for the last fifteen years, curator and art historian Sylvia Chivaratanond has sewn for herself a unique place in this strange Shangri-La’s rich artistic tapestry, which dates back to the 50s and 60s with artists like Ed Ruscha and Billy Al Bengston. After seeing the landmark exhibition Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s, which is widely considered to be one of the most important exhibitions of contemporary art, Chivaratanond switched her major from law to art history, volunteered to be a guard at MoCA, and began a long career organizing exciting exhibitions for institutions from the Centre Pompidou to the Tate Gallery in London. Recently, Chivaratanond has been brought on the curate exhibitions for After & Again, which is a contemporary art platform celebrating the craftsmanship of textiles. Merging art, design and fashion, the platform sources textiles from all over the world, which are then presented in unique site-specific installations. For the first installation presented by After & Again, Chivaratanond has curated an electrifying exhibition by established and leading contemporary Mexican artist Betsabee Romero, which explores pre-Columbian iconography, colonial imagery, and lowrider culture – it is currently on view at the Masonic Lodge at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. Autre was lucky enough to catch the very busy Chivaratanond to discuss her beginnings in the art world and her continued thirst for exploring new creative landscapes – what you will learn is that she may just be one of the most important ambassadors for the Los Angeles art scene.

Autre: What is your artistic background…how were you initially introduced to the world of art and can you remember a specific work of art that really set you off?

Sylvia Chivaratanond: I am originally from Los Angeles and was a pre-law major at UCLA. As a college sophomore I walked into the Helter Skelter show at MoCA's Geffen one evening, and that show single-handedly changed the course of my life. The following week I marched into MoCA to volunteer as a guard and intern in the Education Dept; switched my major to Art History and didn't tell my parents until six months before graduation day. My world was turned upside down when I saw the work of Charles Ray, Lynn Foulkes, Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Lari Pittman, Jim Shaw, Meg Cranston, Robert Williams, Manual Ocampo, etc. Then I saw Sonic Youth perform at the Geffen outdoor plaza as part of the show and I was hooked. That work spoke to me on so many levels: viscerally, physically, emotionally, and intellectually. And it had a rock star component, which spoke to my youth culture. It was then that I learned that many of those artists taught at the art department of UCLA and several colleges around the city, and I wanted to be even closer to these individuals' energy.

A: How did you get your start in curation and can you describe your first curatorial effort?

SC: After UCLA I went to earn a graduate degree from Leicester University. During my time in London I interned at the Tate Modern for two years and worked very closely with the curatorial department on several Modernist shows. It wasn't until the following year when I received a curatorial fellowship at the Walker Art Center that my expertise in the contemporary art world was cemented. It was there where I met the most creative minds working the field of contemporary art. I was the assistant of Richard Flood, then Chief Curator, and I worked on my first contemporary art show: Matthew Barney's Cremaster 3. In addition, I worked on the drawing retrospective of Robert Gober, Bruce Conner and the most comprehensive Arte Povera show to date. It was a phenomenal time at the Walker as it was a think tank and laboratory for ideas and artists; it practiced what it preached as far as cross-discipline approach to the visual arts. There was an incredible amount of freedom in our thinking and way of looking at art; there was no hierarchy in place. The director at the time, Kathy Halbreich (now Associate Director of MoMA) practiced a special generosity with regard to knowledge and her time that continues to be her ethos till this day.

A: You most recently worked as a curator for the venerable Centre Pompidou…what was most exciting about working with that institution?

SC: The Centre Pompidou is known for its stellar scholarship and excellent collection of art. It was an honor to work with their director and curators on building their permanent collection of art with regard to American artists, a focus for the Centre Pompidou Foundation. I was instrumental in adding important American artists to their collection including Jim Shaw, Rachel Harrison, Cheyney Thompson, Erin Sheriff, Sam Falls, Mark Bradford, Sterling Ruby, Barbara Kasten, Analia Saban, RH Quaytman, among many others.

A: I want to talk about your work with After & Again, which celebrates craftsmanship of textiles…what has your experience been with textiles?

SC: I recognize the importance of textiles in art as they have been part of the fabric of culture since the dawn of time! From what we wear on a daily basis to folk and tribal art to contemporary artists working w fabric such as Sheila Hicks, Ernesto Neto, and Yinka Shonibare. There are so many artists using textiles in their work whether directly sewn or worked into the sculptural object or simply as clothing to evoke an era or statement in a photograph such as Mickalene Thomas. In Mickalene's paintings, even though she doesn't use textiles directly, she makes specific references to them in her work in order to evoke a certain epoch or make a political statement. Do Ho Suh is another artist who comes into mind who weaves intricate sculptural installations from translucent fabric and resin.

A: One of the first exhibitions presented by After & Again is a presentation of works by Betsabeé Romero, which will be on view at the Masonic Lodge, can you describe your connection with this artist?

SC: I have always admired Betsabee's work from a far but never experienced it until now. She is a legend in Mexico and Latin American and I'm thrilled to have the opportunity to bring her work to audiences in Los Angeles. Her work in sculpture, photographs, drawings and installation bridge the gap between Pre-Colombian iconography and pop culture such as Chicano and lowrider culture. The notion of death as celebratory is also a big topic in her work. I have always gravitated toward work that both celebrates and draws attention death in our culture, not so much as a dark component, but instead using darkness as way to generate lightness.

Installation view of Helter Skelter - the show at MoCA that changed curator Sylvia Chivaratanond's life forever

A: Can you talk about future shows presented by After & Again that you are curating?

SC: We plan to choose the next artist by this summer in order to show in Los Angeles in the fall. The artist will also do an edition for After & Again and will somehow integrate that project into an installation at a location in the city.

A: What type of art do you gravitate to the most…is there any type of medium or work that you are immediately drawn to?

SC: I love work in all mediums across eras. I love Surrealist and Dada work and I also love strolling the Metropolitan Museum's collection galleries of ancient south east Asian art and art from the sub-continent from 400 B.C onward!

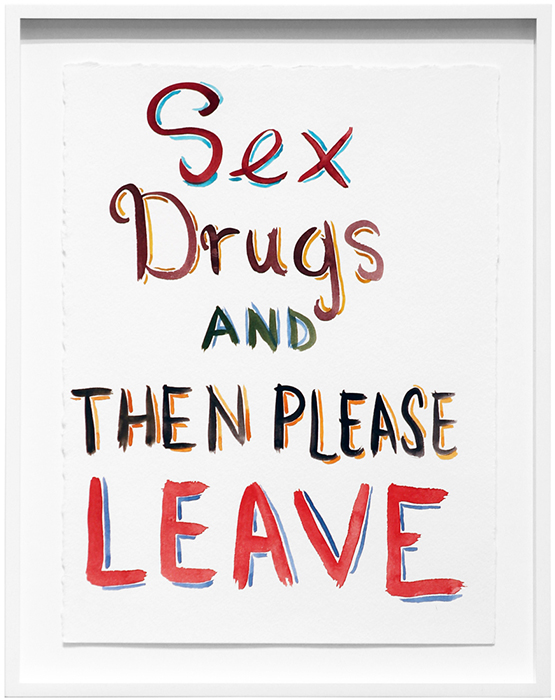

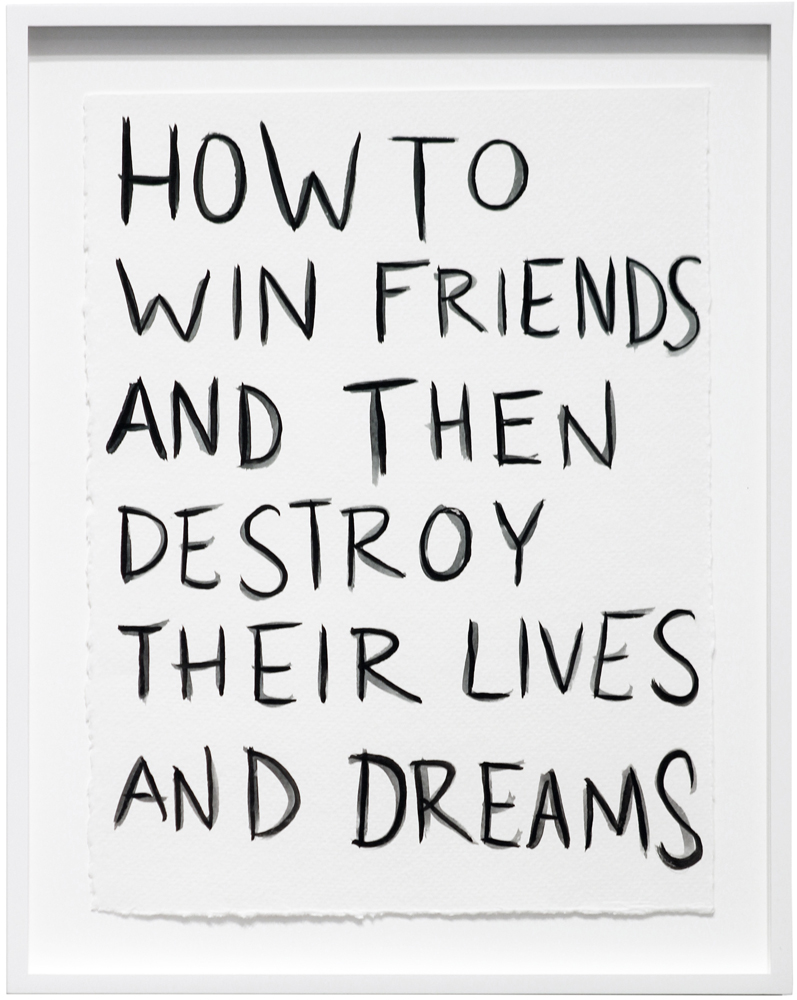

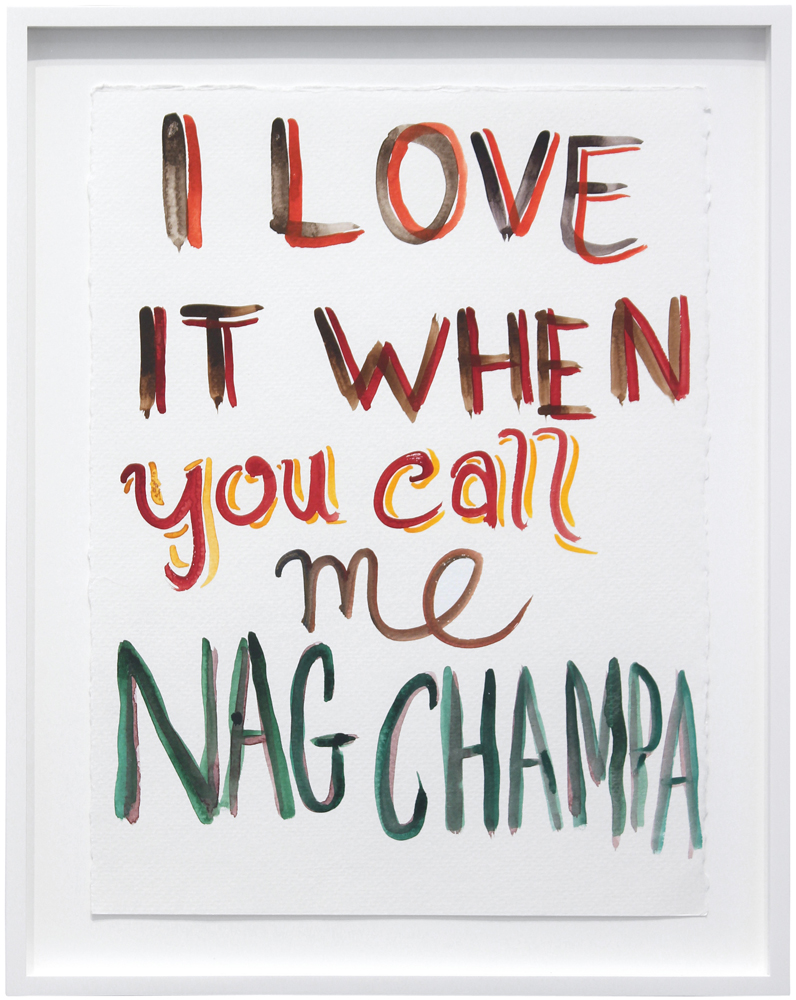

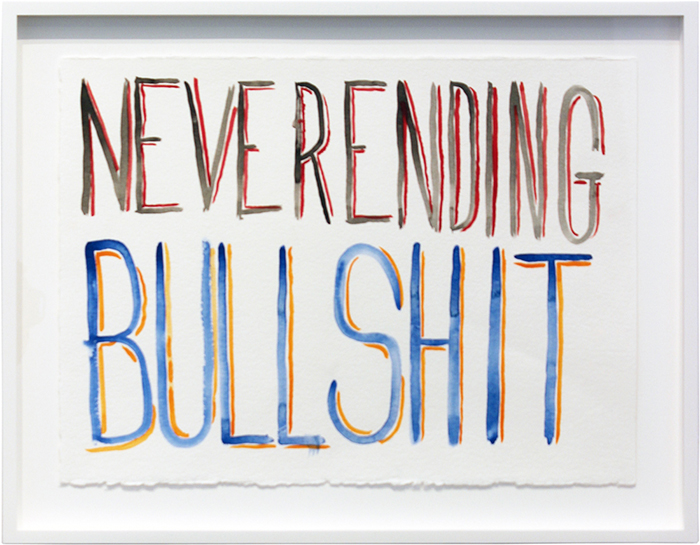

A: You recently curated a show of Devendra Banhart's work at Reserve Ames - what is Devendra doing that is different than other artists?

SC: I love Devendra's seamless fusion of visual art and music. He is the modern day dandy who understands the subtleties of our culture from the history of sound and the works of John Cage to the poetry of Ginsburg to the latest country music. He went to art school first then began his music career, in that order.

A: What is the most exciting thing about art in LA – especially in the present – is there a boom or has there always been one continuous shock wave?

SC: Los Angeles has always been important to the scene of art since the 1950s and 1960s with Ed Kienholz and the birth of Ferus Gallery to all the artists in the now historical 1992 Helter Skelter show at MoCA. Los Angeles has always been in a strong position in the art world as this is the city with the most concentration of the best art schools in the country. The recent boom of art comes at the heels of the revitalization of downtown and with it affordable studios and housing in these dense areas of population. Everyone from New York City has figured out that LA has been inexpensive to work and live (not to mention unbeatable sunshine) so recently there has been a mass exodus of artists, galleries, and collectors from every major city in the world. Did I mention the outrageously delicious food scene here? It's out of this world with the most Michelin star restaurants in one city. Downtown LA is also the home to the most exciting museums from MoCA to the new Broad Museum, which will continue to bring fresh and new perspectives of art while broadening their audiences.

A: What’s next?

SC: For me: yoga and meditation somewhere far off. For art: continue the curiosity that makes art of our time. We must continue to support art, music and culture in any way possible.

You can catch Sylvia Chivaratanond's first curatorial effort for After & Again, featuring the art of leading Mexican artist Betsabee Romero at the Masonic Lodge (6000 Santa Monica Blvd - right behind Paris Photo) from May 2 to May 4, 2015. text and interview by Oliver Maxwell Kupper

FOLLOW AUTRE ON INSTAGRAM: @AUTREMAGAZINE

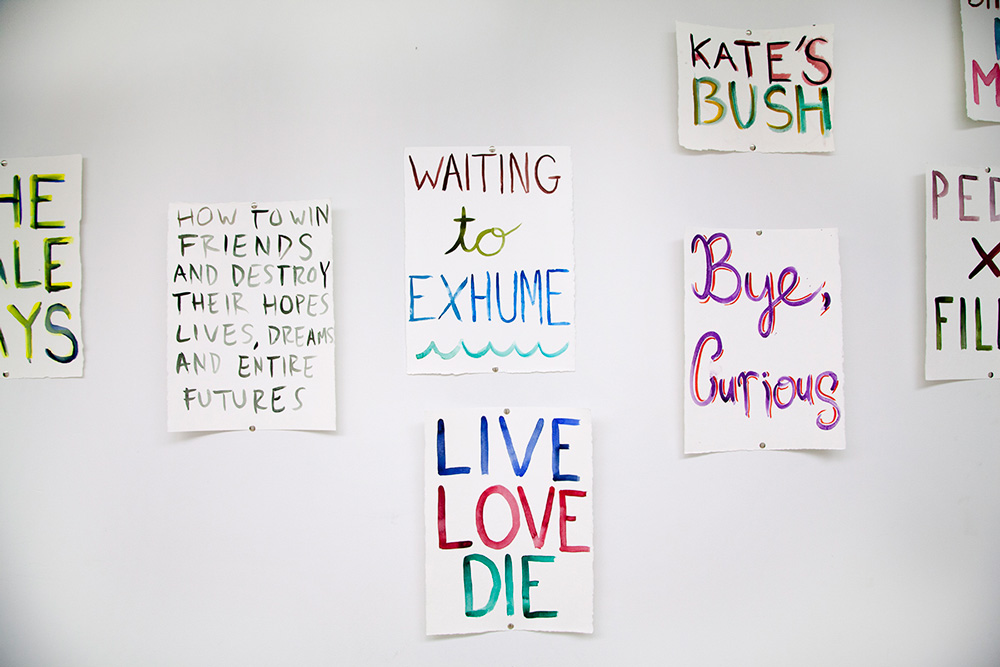

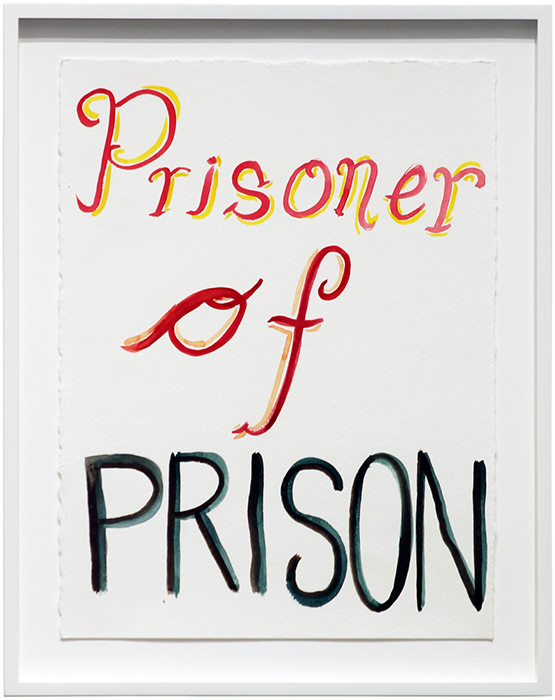

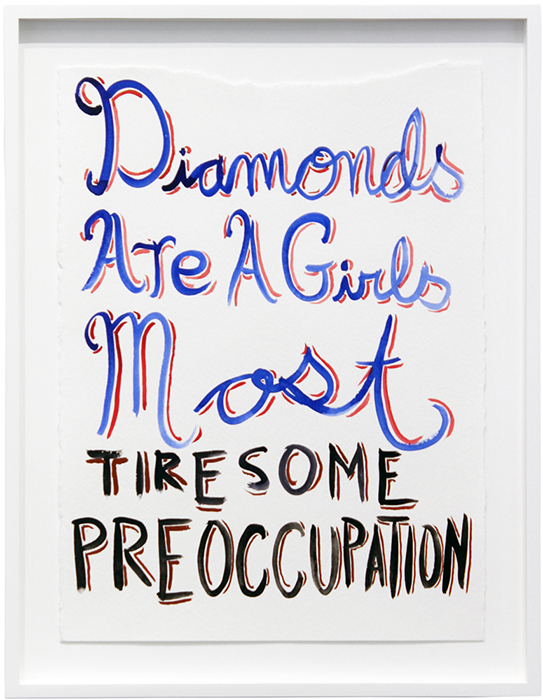

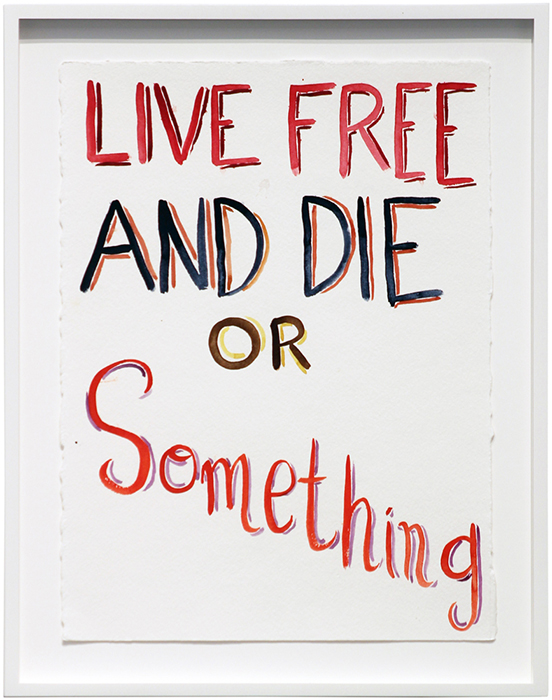

Installation of Betsabee Romero's exhibition at the Masonic Lodge, curated by Sylvia Chivaratanond